"Det är omöjligt att göra ett stort hus osynligt"1, opined once Swedish architect Léonie Geisendorf, 'It is impossible to make a large building invisible'.

Yet while a building can't be invisible, its architect can.

Especially when they are female.

In an eponymous showcase ArkDes, Stockholm, seek to remove the cloak of invisibility that currently shrouds both Léonie Geisendorf and her contribution to the (hi)story of architecture and interior design in Sweden.......

Born on April 8th 1914 as Leonia Maria Kolin-Kaplan in Łódź, then part of the Russian Empire, today Poland, Kolin-Kaplan studied architecture at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Zürich, between 1933 and 1938, a period during which she briefly worked, interned, in Le Corbusier's studio in Paris.

Following her graduation rather than remain in Switzerland, or head east back to Łódź, or west back to Paris, Kolin-Kaplan moved north to Stockholm, where in the course of the 1940s she took her first professional steps in a number of practices and contexts, and married fellow Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule architecture alumni Charles-Edouard Geisendorf, with whom in 1950, the now Léonie Geisendorf, established a joint practice with offices in Stockholm and Zürich.

A 1950s Stockholm in which, in many regards, Léonie Geisendorf at ArkDes opens with the 1956 Nordisk Resebureau, a three storey office space, public space, and cinema, interior design project on Stureplan in downtown Stockholm, realised in cooperation with Charles-Edouard; an interior whose inclusion of a cinema in a 1950s travel agency implies a very contemporary approach to selling a tourism that is not yet mass but becoming increasingly professional. And an interior that, to judge from the photos on show in Léonie Geisendorf, wouldn't have looked out of place in a mid-1950s USA, thus very much reminding of the more or less contemporaneous SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen; and thereby helping remind that architecture and interior design in Sweden, in Scandinavia, aren't, and weren't always, reduced wood and the "time-honoured tradition and quality craftsmanship" of a Jørgen Roos. Or of the contemporary Swedish furniture industry.

A reminder also to be found in the 1960 inaugurated Vocational School for Domestic Education and Needlework, a work in concrete, steel and glass that owes more than a nod of thanks to the positions of Le Corbusier; a representation of 1950s Brutalism defined to a large degree by its prefabricated concrete windows, thus allowing it to stand in/on Stockholm's Kungsholmen district as an example of the demand for novel methods of construction that, in many regards, was more central to the arguments of the Functionalist Modernists of the 1920s and 30s than the formal expressions those arguments took, a fact all too often forgotten today in our visual society. As is the demand that novel methods needs must always develop in context of, in discourse with, novel forms. And a representation of 1950s Brutalism in a building intended to a house an institution with a social view from the 1850s: the tension in the irony is almost unbearable. As is the questioning of Sweden's famously equitable society. And a mismatch of building and content that reminds of that moment when, as noted from Bauhaus and National Socialism at Klassik Stiftung Weimar, the NSDAP housed the Landesfrauenarbeiterschule, a school for 'traditional' female arts and crafts, and for reinforcing invented regional identities, that can very much be understood as a component of the NSDAP's völkische narrative, in Gropius's Bauhaus Dessau school building with its international perspective. A deliberate reappropriation of Gropius's world-view on idealogical grounds. In Stockholm either no one saw the discrepancy between building an content, or did but didn't care.

And a building whose construction, as one can read in a selection of letters on show in Léonie Geisendorf, Léonie Geisendorf not only personally managed but regularly had to fight to ensure her vision was realised. Fight tenaciously. And thus for all it is officially a joint Geisendorfs project, we'll argue, can very much be considered a Léonie Geisendorf project. A Léonie Geisendorf project that, as one can also read in Léonie Geisendorf, wasn't without its controversies.

If much less controversial than Léonie Geisendorf's plans for a new Catholic church on Kungsträdgården in central Stockholm. A project that, as can be followed via sketches, models, letters and newspaper articles, was commissioned in 1963, thus in a period of demolition and rebuilding in central Stockholm, an example of that Remove. Rebuild. Repeat. that Rip It Up and Start Again that, as discussed from Demolition Question at the Deutsches Architektur Zentrum, DAZ, Berlin, has for so long dominated European architecture and urban planning. A Catholic church that initially presented itself, again, very much with a nod to Le Corbusier, as a facade defined by an arrangement of varied volumed and aligned quadrats reminiscent of Constructivist art; a facade whose visible volumes may or may not have related to the volumes behind it; a facade that for all it references the classical arrangement of its (proposed) neighbours, does more so as a paraphrasing than a direct quotation. And a facade that played a leading role in the heated, and long, discussion about whether the church disfigured or embellished its prominent site.

A discussion that was ongoing when Stockholm City Council changed its official policy, as a Lucius Burckhardt never tires to remind us planning authorities invariably do, and decided against wide-scale demolition, a rare decision against Rip It Up and Start Again, and thereby decided against allowing the existing building to be demolished to make way for the church. A change of position that forced Geisendorf to submit a new plan retaining the original facade; a new plan that remained as unrealised as the original Constructivist proposal.

And as unrealised as her early 1970s proposal for, studies of, prison cells, a very specific case of interior design, and which, as one can glean from Geisendorf's sketches, was based on human proportions, whereby arguably more the actual human proportions of a Kaare Klint than the abstracted Modulor proportions of a Le Corbusier, and of treating prisoners more as humans than an abstracted problem. Prison cell studies whose models the curators have chosen to set in conversation with the models for the Catholic church on Kungsträdgården, which may or may not be a comment on the cell as basic unit of life and of the ancient monastery, may or may not be a comparison of prison as an institution with the Catholic church as an institution, may or may not be a response to the lack of space within ArkDes.

Prison cell studies that also included suggestions for colour schemes and furniture, including, again if we've understood correctly, the use of Axel Kandell's 1948 Cattelin chair for Gemla, a chair in bentwood and moulded wood that in its referencing works by 19th century Thonet, a regular referencing of Thonet in the Gemla portfolio, reinforces the links between Gemla and Thonet as personified by the workers who travelled from the Thonet factories in Bohemia to Sweden in the 19th century and helped lay the foundations for the contemporary Swedish furniture industry. While the regular referencing of 1920s works for Viennese based manufacturer Haus und Garten in the Gemla portfolio helps reinforce the importance of Vienna's Josef Frank on the development of furniture and interior design in Sweden. And thus a Gemla that is as instructive and informative about the 'Swedishness" of 'Swedish' furniture design as a Léonie Geisendorf is instructive and informative about the 'Swedishness' of 'Swedish' architecture and interior design.

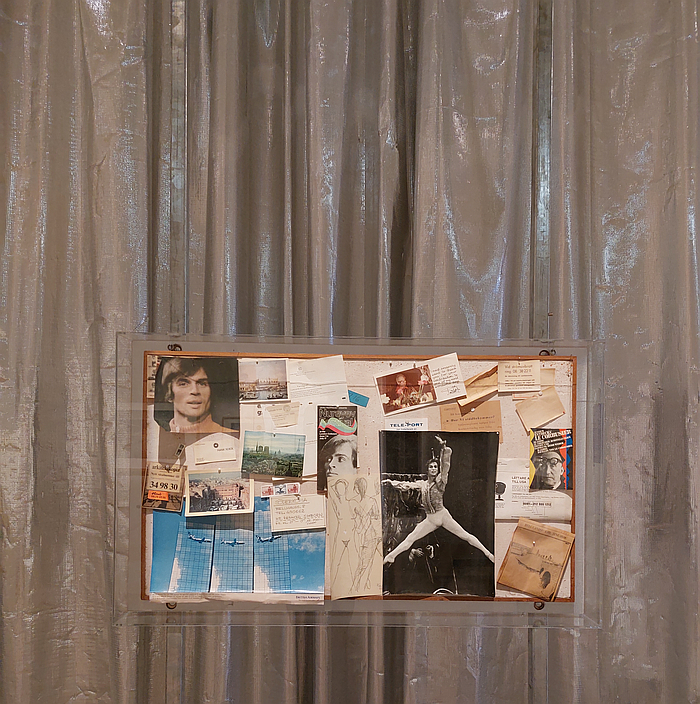

A bijou showcase based exclusively around material from the Geisendorfs' archives as maintained by ArkDes, Léonie Geisendorf provides for the briefest of introductions to the work, positions, motivations of the architect Léonie Geisendorf, and also brief insights into the person Léonie Geisendorf via the pin board from her studio, an object which tends to imply that the Russian ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev was almost as influential as Le Corbusier, if we did admittedly fail to find the flowing movement, and subtly energy, of a Nureyev in the four projects presented, and also via 80 slides from the thousands Geisendorf made on her regular travels.

Or 80 slides that should provide for insights into the person, and possibly, the architect, Léonie Geisendorf; sadly the projector was broken on the day we were there and so we're unsure of exactly what they show. Or the gaze they are taken from. On a similar note, it is regrettable that in an otherwise bilingual Swedish/English presentation the 1961 TV interview with Geisendorf is only in Swedish, and thereby inaccessible to non-Swedish speakers. As noted from Bruno Tomberg. Inventing Design at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, Tallinn, one of the major hurdles to better appreciating a global architecture and design that often communicates in a common language is the lack of a common global spoken language. A hurdle translations can effortlessly circumnavigate.

An introduction that very much implies a much more expansive Léonie Geisendorf exhibition is not only waiting to be made but needs to be made; an introduction that you can, should, expand upon by reflecting of Léonie Geisendorf's work, positions, motivations in context of the projects presented in the neighbouring ArkDes permanent collection exhibition, projects primarily by, very visible, men. And also expand upon out on the streets of Stockholm. Not least at the site of Geisendorf's vocational school on Sankt Göransgatan that can't be hidden and her unrealised Constructivist church on Kungsträdgården that a great many didn't want to see.

But for all is an introduction to Léonie Geisendorf that underscores that the popular narrative of architectural (hi)story in Sweden, and by extrapolation globally, contains a lot than is unseen, a lot that is invisible from our contemporary perspectives, and that is in urgent need of better illumination, by way of enabling the more probable, and more meaningful, narrative of the (hi)story of architecture and interior design in Sweden, and beyond, we all need and require to help us move forward.

Léonie Geisendorf is scheduled to run at ArkDes, Exercisplan 4, 111 49 Stockholm until Sunday October 5th.

Further details can be found at https://arkdes.se

1Léonie Geisendorf from an interview for the Swedish TV programme Hus och stad, 1961, quoted in Léonie Geisendorf, ArkDes, Stockholm