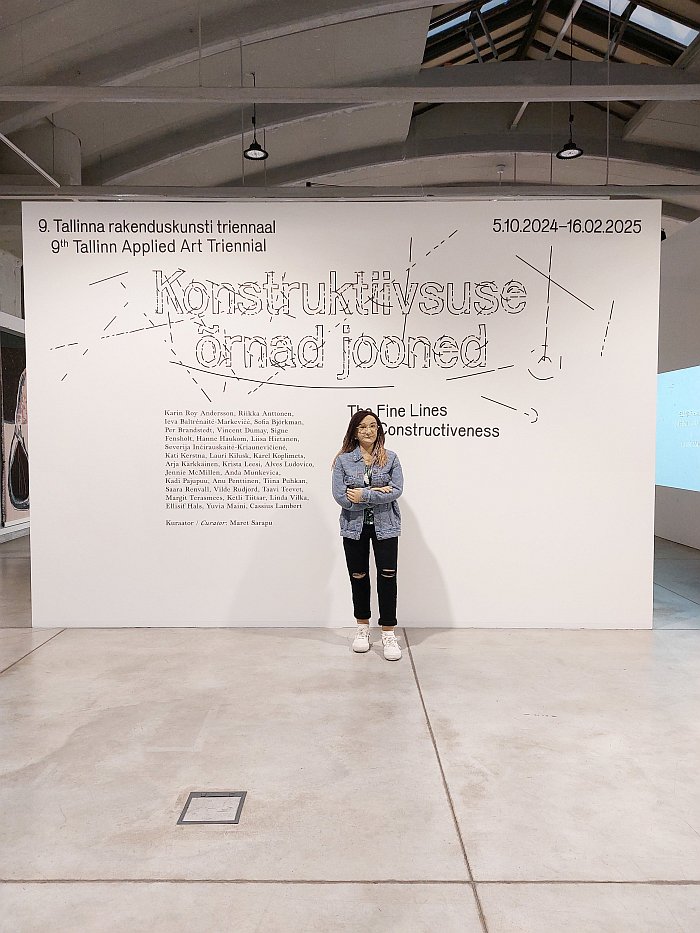

Inaugurated in 1997, Tallinn Applied Art Triennial is a curated platform for contemporary creatives of all hues staged around, in dialogue with, a unifying theme/topic, and which presents itself as both a central exhibition and a series of satellite events throughout the Estonian capital.

A platform that after being open to creatives based globally for its first 8 editions, was restricted for its 9th edition to global creatives based in the Baltic and Nordic nations.

Why the change? We no know. Yes, we could have asked. Probably should have asked. That we didn't ask isn't because we find the question irrelevant, we don't, it is very relevant, and we're also very much against any geographic restrictions in such contexts. We would like to know why the restriction was introduced. That we didn't ask is primarily because the 9th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial has now ended, and so the question isn't one for here, but very much one to be posed in context of the open call for the 10th edition due in 2027.

Or put another way, the 9th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial is now (hi)story.

Or at least is physically (hi)story: the works, the positions, the contexts, the conversations however continue to be very much part of the now.

Which is why we're posting these thoughts and reflections despite the event itself no longer being on.

And also because even if it was still on, the greater majority of you wouldn't have made it to Tallinn on time, we only just got there ourselves despite it running for four months and having been planning to visit for the greater part of those four months; however, other things just kept getting in the way. For the greater part of winter 2024/25 Tallinn has been just a day too far away. A component of a universal truth that it doesn't matter how long an exhibtion, design week, biennial or triennial is on for, if you're not physically in that location when its on, you can't see it.

Which is also why we're positing, we were there, are the opinion you should have been as well, and so.......

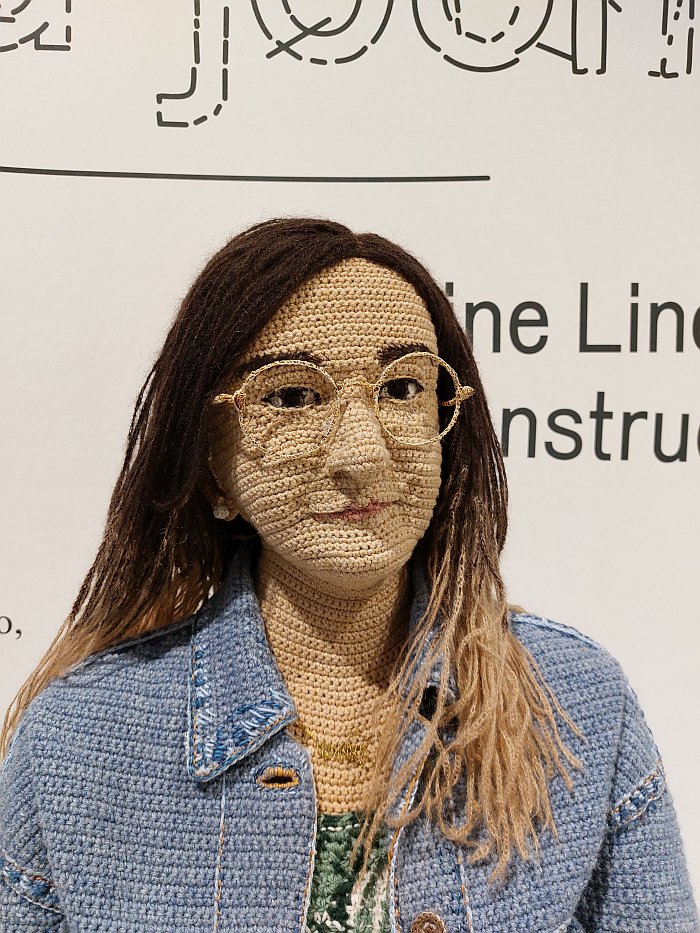

Curated by Estonian glass artist Maret Sarapu under the theme The Fine Lines of Constructiveness, a constructiveness in art that for Sarapu means "a willingness to experiment, innovate and make something new, to look for unexpected collaborations, to approach issues in a practical manner" and as expressed via projects that, for Sarapu, "provide us with ideas and the stamina to live a better life", specifically projects that represent "strategies not models. Not all questions have definitive answers".1 Which, yes, could cause us to refer to a Lucius Burckhardt; but we'll resist that particular temptation and instead note that the 9th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial received a record number of 470 applications, so obviously the geographical restrictions had no negative effect, the largest contingent coming from Finland, closely followed by Estonia and Sweden; 470 from which 28 creatives were ultimately selected for the main exhibition in Tallinn's Kai Art Center.

28 creatives who work in vast array of materials, and from at times greatly contrasting positions and starting points, to produce works utilitarian and decorative, works based in craft and novel technologies and craft through novel technologies, works social, activist, contemplative, humorous, thought-provoking, works speculative and pragmatic; and works from which our attention was particularly caught by.......

Arising in context of the lockdowns of the Covid years, the project Sports at Home by Lithuanian textile artist Severija Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė takes sport equipment that became obsolete during, on account of, those lockdowns and crafts a new use for them, a new use very much focussed on the home that we were all, then, spending an awful lot more time in that we would otherwise have chosen to.

And while, admittedly, not so keen on the rugs crafted from sports balls and sports shoes, we did spend an inordinate amount of time in conversation with the vases Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė realised, in cooperation with Lithuanian ceramicist Rūta Šipalytė, from old basketballs, footballs, volleyballs etc.

Objects that despite very obviously being industrial waste are very organic, as in natural not curved, although they are also curved: they radiate a warmth that simply cannot come from an old ball, can but come from a vital, independent, being. And also have very much something of the gourd vase about them, a ceramic vase concept that can be traced back to ancient China and which, certainly in the more pumpkin-esque form, was a very popular concept in the 1970s. And thus, certainly for us, vases that exist not only as thoroughly engaging objects whose decorative quality comes from the chance and serendipity of their age and construction, nor only as readymades neatly expanded by ceramic inserts that also creates a pleasing material tension, but are also very much an argument for the need to work in the now, that one, can, should, must, use the formal expressions and stimuli of the past but always in context of our contemporary and in the materials of our contemporary, including using those industrial objects whose original function the contemporary has made obsolete. Just don't call it upcycling, or we'll very, very, cross with you!!!

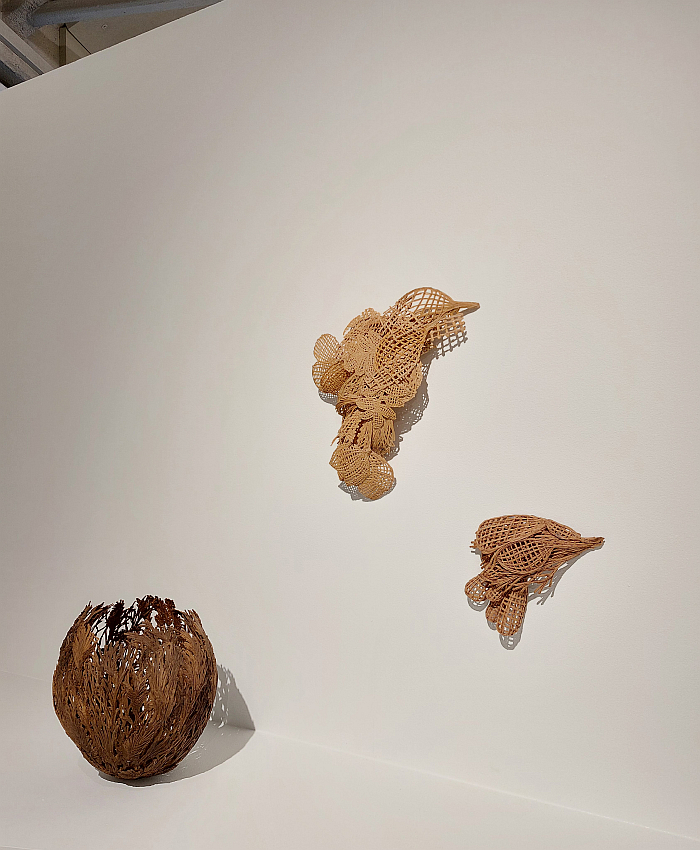

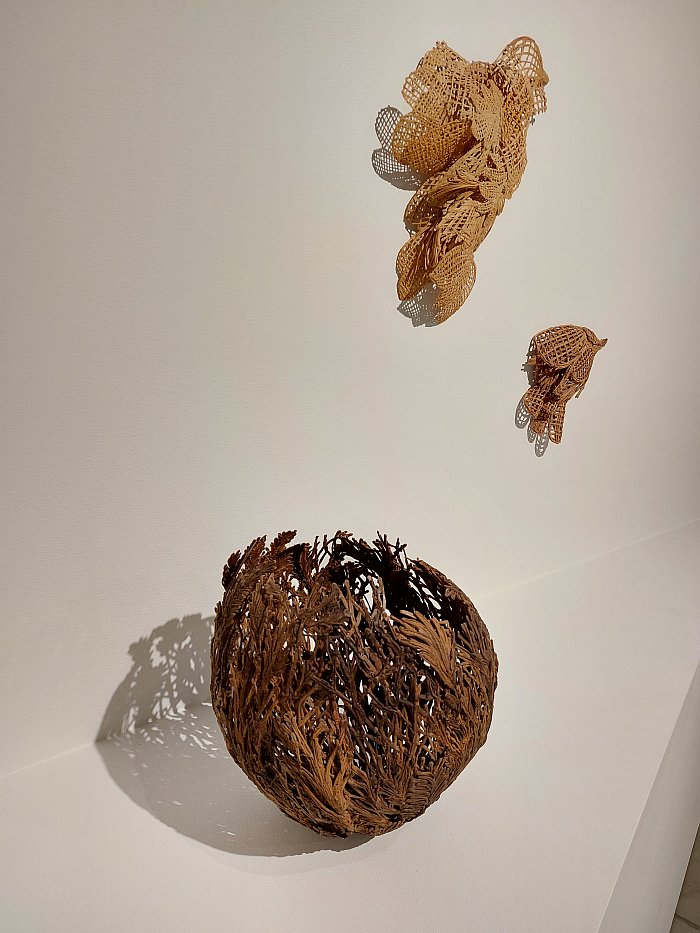

As regular readers will appreciate we're big fans of 3D printing with wood based materials, and have never knowingly walked past a 3D printed wood project. Our attraction to the objects by Stockholm based jewellery artist Sofia Björkman was however initially the questions they posed on basketry in the 21st century, the questions they posed on that craft that, as discussed by and from All Hands On: Basketry at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, is one of the distant past with a lot to offer the future. And which Björkman approaches, essentially, if we've understood correctly, with a 3D printing pen i.e. she draws baskets in space. And does so with a wood/PLA mixture.

We hear you, we hear you, and your right, you can't draw a basket in space. It's simply not possible. But you can reflect on what basketry is, what the weaving of ligneous materials to functional 3D objects in the 21st century is, what the future of basketry is, and if you do, drawing baskets in space with a 3d printing pen employing a wood/PLA mixture is a very convincing answer. Possibly not the only answer. Possibly not an answer that will remain as Sofia Björkman approaches it. But still a very, very, convincing answer. One that requires every bit as much understanding of the material and skilled practice to achieve meaningful results as the basketry of yore.

And an inherent conflict between basketry of the future and basketry of the past in many regards reinforced, brought into the conversation, by the very clear echoes of Art Nouveau in the works by Björkman presented in Tallinn, and which reminds, as Art Nouveau does, that any society should always be at a point of conflict between the past and the future. And that to avoid that conflict is detrimental to that society. As is rejecting that past out-of-hand in the name of the future.

Possibly based on Lithuanian textile designer Ieva Baltrėnaitė-Markevičė's PhD Thesis at Vilnius Academy of Arts, or possibly not, The Secrets of the (Un)Processed Collection has as its focus clothes made by ordinary Lithuanians for their own use between the 1940s and 1970s, and for all the stories associated with those DIY objects, stories hung as labels inside the self-made clothing as if price label. Self-made clothing objects Baltrėnaitė-Markevičė juxtaposes with images from Lithuanian and international fashion and lifestyle magazines of the same period.

A project that is a nice reminder that the fashion industry with its ever new collections and targeted advancing of toxic t*****, that may or may not be new, exists purely to sell things, that there is no other reason for the fashion industry, its magazines, models, tv shows et al; clothing is an essential for which we don't need a global industry telling us what to do, have however become thoroughly dependent on that industry. Worship at the alter of that industry. And thus The Secrets of the (Un)Processed Collection stands as a moment to question not only how we dress ourselves, but how we feed ourselves, how we furnish our homes, spend our free time, holiday, make political decisions, et al.

And also to question the systems and rituals via which we assess and assign a value to any and every object of daily use: what's more valuable one of the self-made dresses in Baltrėnaitė-Markevičė's installation or the dresses on the pages of Vogue? Honestly? Why? Really?

In addition, through linking the individual items of clothing to the individuals who made and/or wore them Baltrėnaitė-Markevičė's also very satisfyingly allows those individuals to contribute to ongoing discussions on not just clothing but Lithuania; allows voices to be actively heard that otherwise would have been lost being as they are outwith the small group of privileged individuals whose voices (hi)story chooses to record. And which is important in ensuring that we better understand how we got to where we are, and we can never have to many voices in that exploration, not least as better understanding the path thus taken is important in enabling us to make the decisions we must make as we move forward.

As we say, the 9th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial has now finished, more information on the event, and at some undefined point in the future details of the 10th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial due to be staged from the autumn of 2027, and which will once again feature a global Open Call, can be found at https://trtr.ee

1Maret Sarapu in Keiu Krikmann, Michael Haagensen, Katre Ratassepp [Eds.] The Fine Lines of Constructiveness, Tallinn Applied Art Triennial Society, 2024