In the early 1980s, Scottish Indie jingle-janglers Orange Juice advised us all to "Rip it up and start again".1

Which has also been the prevailing credo of European architecture and urban planning for much of the past two centuries: less a case of what goes up must come down, as what goes up will come down as soon as a new use is demanded or a new spatial concept developed or a new political ideology comes to the fore.

But should it? Must it? And if didn't?

Questions that in recent decades have increasingly busied individuals of all hues and led to the development of ever more convincing arguments against demolition as a standard practice in and for urban planning.

With the showcase Demolition Question the Deutsches Architektur Zentrum, DAZ, Berlin provide a platform for reflecting on those arguments.......

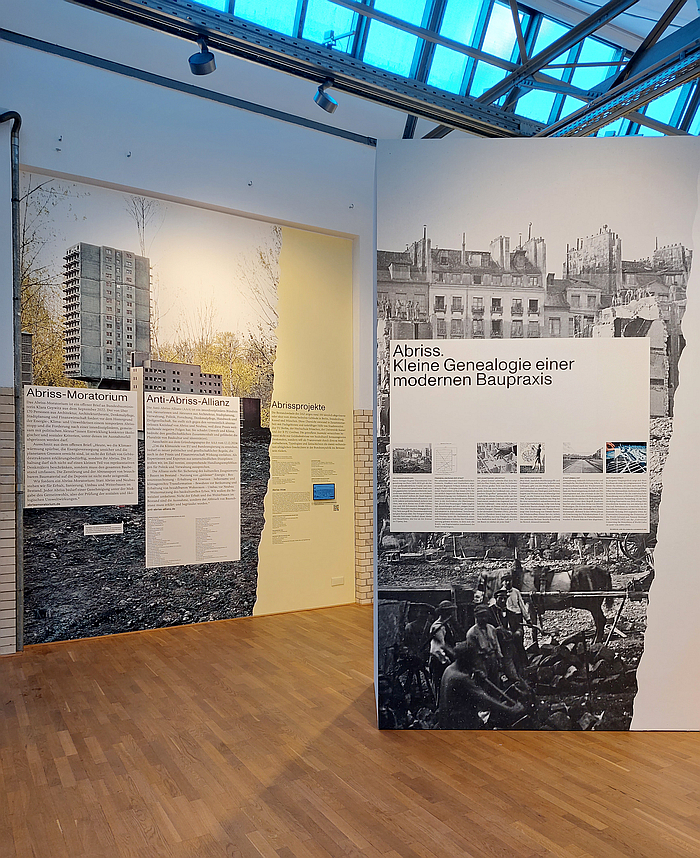

Based on a project initiated by Prof. Luise Rellensmann from the Hochschule München and Dr. Alexander Stumm from Universität Kassel, Demolition Question is, in many regards, a presentation constructed... sorry!!!... from two inter-twinning strands: a discussion on the whys, wherefores and alternatives to and of demolition and a series of illustrative examples.

The former strand including, amongst other themes and topics, an introduction to four grassroots anti-demoliton initiatives in Germany, a discussion on the role of non-building architects in urban planning or the project Power to Renovation, a film project by the HouseEurope! initiative that not only demands more renovation and less demolition but which presents possible legal and economic models and frameworks via which such could be encouraged, supported, demanded, and thus achieved. And also by what the curators refer to as a Kleine genealogie einer modernen Baupraxis, A short genealogy of a modern building practice, starting from Georges-Eugène Haussmann's massacring of 19th century Paris, and moving over Reginald Pelham Bolton's 1911 publication Building for Profit an early argument for land and building speculation as a driver of growth, the utopias of the early 20th century avant-gardes, the post 1939-45 War reconstruction in Europe, the post-1989 spatial re-planning in the former DDR, that in many regards stands proxy for all built environment change after fundamental political/demographic change, and on to the so-called Star Architect, that oh so dangerous, objectionable and superfluous creature. And thereby also introducing a variety of reasons for the fascination with, arguments for, demolition as a process in architecture and urban planning that for all many of them may sound historic, aren't.

A contemporaneous that can be approached and reflected upon in the second strand via the so-called Abriss-Atlas, Demolition Atlas, and its examples of buildings either in danger of demolition or that have already gone, in Kassel, Munich, Berlin and the State of Brandenburg, the latter including several in Potsdam that have either vanished or are scheduled to vanish on account of the contemporary obsession of the authorities in Potsdam, and as noted from Re:Generation. Climate change in a natural World Heritage Site – and what we can do about it at Park Sanssouci, to reconstruct Potsdam as it was when the Hohenzollern ruled the region. An obsession to build an imagined, invented, Potsdam of the past rather than a responsive Potsdam of the future. And an associated obsession with removing any and all vestiges of the DDR from the Hohenzollern 's favoured city. No, we don't approve.

If, yes, part of the reason for that rebuilding is the loss of the buildings that were once there, several at the behest of the DDR authorities. But which doesn't in itself justify the demolishing of the buildings that are now there.

Not that there are never justifications for demolition.

There often are.

Are, without question, often valid reasons why buildings should, must, be demolished. Eisenhüttenstadt, a location featured in the Abriss-Atlas and, we'll argue, an important component of the post-1989 spatial re-planning in the former DDR discussed in and by the curators short genealogy of a modern building practice, being, arguably, and as discussed by and from Endless Beginning. The Transformation of the Socialist City at the Museum Utopie und Alltag, a very good example of when it can make sense, while also being an admonishment to ensure the bar for making decisions is set high, is set so as to seek to preserve as much as possible of that which exists. As in many regards, if from a different perspective, is the city of Stuttgart, an argument illustrated by and from Stuttgart reißt sich ab. Plea for the Preservation of Cityscape Defining Buildings at the Architekturgalerie am Weissenhof and its elucidation of the ease with which in Stuttgart buildings can be demolished, where, in many regards, demolition is easier and quicker than preservation, renovation and transformation.

Which is all very Haussmann.

All very Orange Juice.

But should it be? Must it be? And if it wasn't?

A text heavy presentation, essentially a poster presentation, which isn't a complaint simply an observation, and a German only presentation which is a complaint, if we do understand and accept why, it's still a complaint, Demolition Question makes very clear that the human-built environment isn't just concrete, brick, glass and metal, isn't just questions of construction, but is also political, economic, ecological and social questions, is inherently political, economic, ecological and social. Which arguably, is one those things that over the past two centuries of ripping it up and starting again wasn't considered.

If that lack of consideration for the immaterial and intangible in the architecture and urban planning of the past was deliberate or accidental is a subject for another day; the subject for today is that we now know better, now appreciate the complexities of the human-built environment.

That we do is, and remaining in the Kassel that is so central to Demolition Question, in so small measure thanks to the work of a Lucius Burckhardt; but he was, we'll argue, a moment in a longer process that, and at the risk of over simplifying, includes a Mart Stam's 1927 argument that we need construction systems that mean "a building, built today as a bank, should be able to be used tomorrow as an office building, department store or hotel"2, which is still form follows function but accepts that neither should be fixed for eternity, and then moves on to a George Nelson's experiences in 1930s Rome where through his youthful architects eyes he wondered at the way one regularly found "three epochs coexisting in one building"3, where buildings were simply changed, added to, adapted, to meet a new use rather than demolished or preserved by state order in a form no longer fit for function, over the 1950s and 60s research of Burkhardt and the myriad international architectural Radicals of various hues, and on until 1968.

A long process that means we now appreciate, not least via projects by Anne Lacaton, Jean-Philippe Vassal and Frédéric Druot such as Cité du Grand Parc, Bordeaux, as featured in Transform at S AM Swiss Architecture Museum, Basel, the social benefits of preserving buildings and thereby maintaining the communities that exist within and around them, those community structures, that, as can be deliciousy understood in several novels from Émile Zola's Rougon-Macquart cycle, for all Au Bonheur des Dames, Haussmann destroyed as freely as he did the physical structures of urban Paris; now appreciate the ecological impact of Remove. Rebuild. Repeat, appreciate the resource usage involved, the energy involved, the greenhouse gas balances, the volumes of rubbish that are produced, none of which we can afford, could ever afford; now appreciate the dangers of the architectural/urban planning Falsche Dominanz, False Dominance, highlighted by the 1972 exhibition Profitopolis or: We need a different city that could also be felt in the exhibition Profitopolis or the Condition of the City at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin, as could the city as a political, economic, ecological and social environment.

Appreciations of the complexities of the human-built environment that demand we approach decisions on urban spaces in context of those complexities.

That we regularly don't brings us back to the deliberate or accidental question in context of the lack of consideration for the immaterial and intangible, albeit in the now. And in context of the ever contemporaneous arguments for demolition contained within the aforementioned short genealogy of a modern building practice.

A deliberate or accidental question the whys, wherefores and alternatives strand very much answers in the former, positioning itself as it does very much as anti-demolition, pro-renovation, and audibly suspicious of the motivations of the global construction industry and its political and financial backers, dependents. A positioning that it doesn't hide and which therefore enables you to engage in an open discussion with its arguments. You don't have to agree with the positions presented. But you do have to think about them.

The Abriss-Atlas is much more open, takes no real position; rather empowers each and every visitor to reflect on the individual examples as independent instances rather than components of a wider discussion, and thereby to focus on the necessity or otherwise of the demolition at hand and thereby to reflect on and consider how the urban planning question is approached.

Reflections and considerations you can then, must then, continue on a self-initiated tour to not only some of the Berlin sites listed on the Abriss-Atlas, but also in the immediate vicinity of the Deutsches Architektur Zentrum, DAZ, an areal you don't have to know, as we do, from earlier days to appreciate the amount of demolition and new construction that has taken place in recent years, it's all very tangible. And an areal where there exists, diagonally opposite DAZ, a fascinating example in the shape of Køpi, a building which has been squatted since 1990, that over the years became accompanied by a sprawling village of caravans and huts, until that village was forcibly cleared, arguably forcibly demolished, in 2021, a clearance/demolition that was intended to include the demolishing of the primary Køpi building. A demolition that the courts have stopped, potentially only temporarily. See A short genealogy of a modern building practice. And a Køpi which thus poses all manner of differentiated urban planning questions that neatly expand on those posed in DAZ.

Urban planning questions that are for all of us, that one important, fundamental, change since the reign of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, but in which we needs must be active, otherwise others will make decisions on our spaces on our behalfs, which is why it is important that we all concern ourselves with the myriad, complex, inter-twinned, themes involved, all busy ourselves with urban spaces in all their complexity, and don't let ourselves get distracted by an architects' simplified storytelling. Certainly not the simplified storytelling of an architect popularly confused for a celestial body.

As a platform Demolition Question is very much an open invitation to approach those complexities through the posing of a question that is still reguarly seen as, accepted as, an answer.

Demolition Question is scheduled to run at the Deutsches Architektur Zentrum, DAZ, Wilhelmine-Gemberg-Weg 6, 10179 Berlin until Sunday May 18th. We suspect it will subsequently take itself off on a German tour, watch local press for details.

Further details can be found at www.daz.de

In addition a book is available, as with the exhibition in German only, via Jovis Verlag

1First released on the 1982 Album Rip It Up, Polydor, POLS 1076

2Mart Stam, M-Kunst, i10 International Revue, 1/2 1927

3George Nelson, Peak Experiences and the Creative Arts, Mobilia 265/66, 1977