The (hi)story of architecture and design is a rich, vibrant, complex smörgåsbord, albeit one that for decades has been popularly reduced to a simplified, formalised, ultra-processed ready meal. Something to re-heat and consume without enjoyment.

A most unhappy, and unhealthy, state of affairs we feel it is our duty to respond to by serving you up some titbits and morsels from that original smörgåsbord, not so that you can go around showing off on social media, please don't, but by way of stimulating you to research further, of stimulating you to read further, to view further, to stop employing lazy catch-all terms as if they had an actual meaning, and thereby allow you all personally to contribute to a restoration of the smörgåsbord of architecture and design (hi)story to its glorious, delicious, richness, vibrancy and complexity. To enable it to not only to nourish us all, but to invigorate and empower us all.

Starting with the not inappropriate titbit that the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was first sketched on the back of a cocktail napkin.

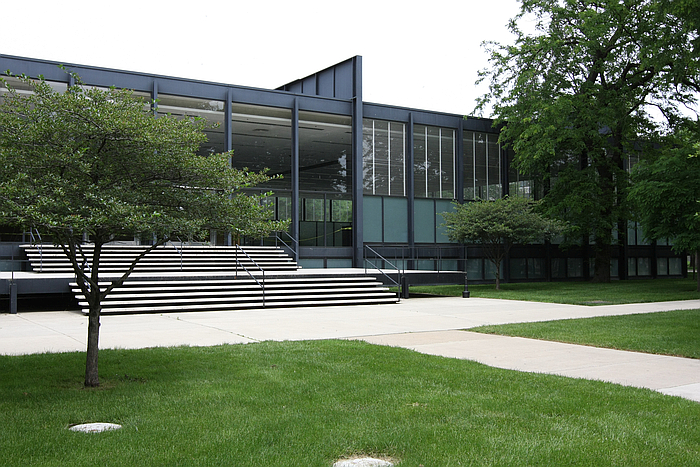

In Havana, Cuba.

Specifically, the work was first was designed in 1957 in context of a commission for an administrative building for Ron Bacardi y Compañía in Santiago, Cuba, a commission awarded by Bacardi President José M. Bosch personally after he'd visited Mies van der Rohe's Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, and recognised in Mies van der Rohe and architect who both spoke a language he understood and who could realise his "ideal office", namely one where "there are no partitions, where everybody, both officers and employees, are seeing each other"✤. We'll leave you to consider that statement, and its definition of an "ideal" office, yourself, not least in context of the office as a means of control, as a methodology of control, and the contemporary debate on home office, hybrid working, compulsory office attendance, mouse trackers et al.

Having accepted the commission Mies van der Rohe travelled to Cuba to view the site with, essentially, the plan of creating something very, very similar to Crown Hall; however, he very, very quickly realised the sun, the light and the salty sea air of the Caribbean wouldn't be conducive, physically or conceptually, to such a work, and thus began rethinking. A process that reached its Eureka! moment in early July 1957 in the garden court of the Hotel Nacional de Cuba, Havana, in which he was staying: inspired by the form, proportions and repeating columns of that arcade bordered garden court Mies van der Rohe asked Gene Summers, one of his long-term senior staff members, to sketch the idea he was having; Summers grabbed a nearby cocktail napkin and visualised his boss's words. Looking at Summers' sketch Mies responded, "No, it looks like a consulate, one Gropius would do", Ouch!!! Mies suggested Summers remove some of the columns, "That's it", Mies responded, "let me have it".✱

From that cocktail napkin the sketch was transferred to, and expanded upon, hotel note paper and subsequently a building began to rise from the ground in Santiago. And then in September 1960 Fidel Castro, now safely ensconced in Havana, nationalised Bacardi: Bacardi ceased to be the international brand it had been prior to the Revolution, became a Cuban brand, a component of a post-Revolution Cuban identity, and construction on Mies van der Rohe's stridently international administrative building ceased.

Never to start again.

Or at least not in Santiago.

For when commissioned in 1962 to build a new museum for 20th century art in Berlin Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had an answer in his desk drawer; a building that echoes the work of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, that defining architect of 19th century Prussian Berlin, an important, defining, early influence on Ludwig Mies van der Rohe that remained with him informing his work, his architectural and furniture work, for what is the base of his and Sergius Ruegenberg's Barcelona Chair if not a reimagining of Schinkel's ever informative and instructive early 19th century cast iron garden chair, that serial, industrial chair from an age before serial, industrial furniture production. And a building with an internal space in which, to paraphrase José M. Bosch, there are no partitions, where everybody can see everything all the time. If that is an 'ideal museum' space is a thought we'll, again, leave with you.

Thus since 1968 the Bacardi y Compañía administrative building has stood not in Santiago but in Berlin.

Although that it does, is only thanks to the fact it wasn't built in Schweinfurt, Bayern, in 1962.

But that's a titbit for another day. Or for own research.

As is the Bacardi administrative building by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe that opened in Tultitlán, Mexico, in 1962 (completed 1961) and its role in both the (hi)story of post-Cuban Revolution Bacardi as an identity tool and the development of architecture and design in a 20th century Mexico that was as much inspired by international positions as it inspired international positions.......

Bauen + Wohnen, September 1959: Bürogebäude der Ron Bacardi & Co. in Santiago, Cuba, 313-315; Verwaltungsbau Bacardi Rum Co. in Mexiko, 316

Bauen + Wohnen, October 1962: Verwaltungsgebäude Ron Bacardi bei Mexico-City, 407-411

Bauwelt Vol. 52, Nr. 13 27. März 1961: Features a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe 75th Birthday tribute; Verwaltungsgebäude der Bacardi Rum Gesellschaft in Mexico-City 1958, 368-369; Verwaltungsgebäude der Bacardi Rum Gesellschaft in Santiago de Cuba, Kuba 1958, 370-373

Bauwelt Vol. 53, Nr. 32, 6. August 1962: Verwaltungsgebäude Ron Bacardi, S.A. bei Mexico City, 886-888

Bauwelt Vol. 59, Nr. 38, 16. September 1968: Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, 1209-1220; Oeter, H & Sontag, H, Das Stahldach der Neuen Nationalgalerie in Berlin, 1224-1226

Carranza, Luis E. & Lara, Fernando Luiz, Modern Architecture in Latin America. Art, Technology, Utopia, The Universiy of Teas Press, Austin, 2014.

Deutsche Bauzeitschrift, Januar 1969: Die Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, 19-24

Futagawa, Yukio [Ed.] GA Global Architecture, Mies van der Rohe. Crown Hall, ITT, Chicago, Illinois USA 1952-1956. New National Gallery, Berlin, West Germany 1968, A.D.A. Edita Tokyo, 1972.

Jäger, Joachim & von Martin, Constanze, Neue Natonalgalerie. Das Museum von Mies van der Rohe, Staatliche Museeen zu Berlin, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin & München, 2021

Juárez Chicote Antonio, El todo en el fragmento. Arquitectura y Baukunst en Mies Van der Rohe, Cuadernos de Proyectos Arquitectónicos, Núm. 4, 2013, 64-71

Kahlfeldt, Paul & Lepik, Andres, Dreissig Jahre Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Berlin, 1998

Kathryn E. O'Rourke, Mies and Bacardi: Mixing Modernism, c. 1960, Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 66, No. 1, October 2012, 57-71

Krohn, Carsten, Mies Van der Rohe. Das Gebaute Werk, Birkhäuser, Basel, 2014

✤ Lambert, Phyllis [Ed.], Mies in America, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal & Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 2201 Quote page 475ff

Lizárraga Sánchez, Salvador, Mies en Tultitlán, Bitácora arquitectura, No. 26, 2016, 83–94

Maibohm, Arne, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin. Sanierung einer Architekturikone, Jovis, Berlin, 2021

Pica, Agnoldomenico, Mies a Berlino: la "Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin", l'ultima grande opera in Europa di Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, scomparso il 17 agosto, Domus, 478, 1969, 1-5

Schulze, Franz [Ed.], The Mies van der Rohe Archive, Volume Seventeen, Ron Bacardi y Compañía S.A., Administration Building (Cuba) and Other Buildings and Projects, Garland Publishing Inc, New York and London, 1992.

Schulze, Franz [Ed.], The Mies van der Rohe Archive, Volume Eighteen, Ron Bacardi y Compañía S.A., Administration Building (Mexico) and Other Buildings and Projects, Garland Publishing Inc, New York and London, 1992.

✱ Schulze, Franz & Windhorst, Edward, Mies van der Rohe, The University of Chicago Press, 2012 Quote page 349