"Ich habe mit der Designwelt ja eigentlich nicht zu tun", opined once Luigi Colani, 'I have nothing to do with the design world', continuing that, 'I would locate what I do very close to the philosophy of form'.1

With Luigi Colani – Shapes of the Future, Marta Herford allow one to not only approach a better appreciation of Luigi Colani's formal philosophy, but in doing so to both question Colani's relationships with a design world he rejected, and that regularly rejected him, and to question his design, his approach, his character and thereby to better approach questions of his legacy and his contemporary relevance.......

Born in Berlin on August 2nd 1928 as Lutz Colani, before adopting the monicker Luigi in 1957, (primarily) because the most successful designers of the late 1950s were Italian — much as in 1922 Ludwig Mies added a 'van der' to his mother's maiden name, 'Rohe', and thereby extended his name to make him sound Dutch, as many of the leading architects of that period were — we discussed the Lutz/Luigi Colani biography in our post on and from Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, and so refer you there dear reader for details, and dive here straight into Luigi Colani – Shapes of the Future, an exhibition that has no natural path, no optimal path, through it, and which, much like the Colani canon, it's difficult, and not necessarily helpful, to say where you could or should begin, the best option is simply to begin and see where it takes you. You're going to keep criss-crossing your path in any case in order to compare and contrast, for, much as Luigi Colani's work rarely expresses itself with a direct straight line, so to can no exploration of Luigi Colani's work be truly linear.

For our part we'll start our discussion on Shapes of the Future with the chapter exploring Colani and transportation; and start there not least because it is one of the larger chapters in Shapes of the Future.

And also one of the larger, and more important and instructive, genres of Colani's oeuvre, in many regards the one permanent, ever present genre of the Colani oeuvre; a genre explored and discussed in Marta Herford via a wide variety of vehicles, a wide variety of transport formats, including, for example, a Colani-2er 2 seater bobsleigh from 1985 for the Bob und Schlittensport Club Winterberg; his 1950s Colani GT kit car, a fibreglass body to be mounted on a VW Beetle chassis that can and must be understood as a direct criticism on that most German of car manufacturers and by extrapolation on the post 1939-45 War West German automobile industry; a mid-1960s pram for Excelsior International whose presence surprises and in doing so neatly disarms any preconceptions you may have brought into the exhibition hall with you. And also by the so-called Colani Truck, one of Colani's longer term projects, presented in Herford as both scale models and as an actual fibreglass cab, or at least the remains of an unfinished, raw cab, and a work that provides succinct insights into not just Colani's positions on form, his philosophy on form, his shapes of the future, nor only his attempts to reform the automotive industry, to shape the future automotive industry, but also that way Luigi Colani was always thinking differently to, arguably, everyone else, that way he viewed objects of all genres from different perspectives than, arguably, everyone else, his distance to prevailing conventions and norms, and thereby enabling him to develop singular expressions of those objects.

And a Colani Truck that also provides for succinct insights into the resistance from industry, be that the automotive, furniture, clothing, homewares, etc. industry, he encountered: or put another way, for all that Luigi Colani continually sought to reduce resistance in his automotive designs, he himself tended to be subjected to a continuos, extreme, resistance, and that, inarguably, not only on account of the singularity of the positions he represented, the unfamiliar he brought to the familiar, but also, arguably for all, on account of the persona Luigi Colani.

A persona that is omnipresent in Shapes of the Future. You simply cannot escape it. Nor can you escape the myriad means via which Colani articulated, and reinforced, that persona, via which he, arguably, we sadly never met Lutz/Luigi Colani and thus can only speculate from afar, carefully constructed and cultivated the Colani persona, be that through, for example, the clothing and accessories he wore and designed, or the placing of his signature on (near) anything and everything he designed, a signature whose function is effortlessly mediated by Shapes of the Future, and makes the branding iron with the Colani signature appear like a weapon rather than a workshop tool; and a signature that regularly found its way into product names, as you may have noted in the above listed examples of his automotive design. And the great many examples still to come.

And a persona also articulated and reinforced by the rants, the insults and the claims of greatness, of superiority, of being overlooked and undervalued, Colani regularly made. Rants, insults, claims that are primarily present in Shapes of the Future via a trio of videos in which Colani comes to word, videos presented in a dark, enclosed space, which isn't necessarily the best environment to be exposed to the rougher edge of the Colani tongue, if it does allow for neatly differentiated considerations on that tongue, and a questioning of the persona, the rants, the insults, the claims, a questioning of how much is and was real, how much is and was show, and how, ¿did?, the relationship between the real and show shift with time? We all get a little more cantankerous with age, all begin to question if our story is good enough to be remembered when we're no longer personally there to tell it, ¿will we be the subject of museum exhibitions? Was that perhaps amplified in a Luigi Colani through years of a carefully constructed and cultivated show confusing reality and fiction? Or was he really so? Was he simply the embodiment of an out-of-control self-confidence fuelled by an unhealthy mix of narcissism and paranoia his rants, insults and claims strongly imply he was? As a young man he did change his name to evoke an alternative biography for commercial benefit. As did a Ludwig Mies who (hi)story hasn't recorded as the most personable nor approachable, nor honourable, of architects.

But for all is a concentration of videos in an enclosed space that allows for a questioning of, if, Luigi Colani wasn't occasionally correct. If Luigi Colani's view of objects of daily use, on the shapes of objects of daily use, on the relevant foci when designing objects of daily use, weren't correct.

Through presenting himself and his arguments in very uncouth and highly objectionable formats, all clear thinking, social, individuals tended to assume he was wrong. Wanted him to be wrong.

¿But was Luigi Colani occasionally, ¿potentially regularly?, correct?

¿And if he was?

A question that one is continually confronted with in Shapes of the Future, and which, and staying in context of the transportation we were dealing with, and the rough tongue with its rants, insults and claims we've just been exposed to, is very neatly illustrated by a passage in one of the videos in which after accusing the automobile industry of always making things more complicated rather than simpler, adding "but what's the point of calling people idiots? There's no point at all. They're not. They're just over intelligent and working against themselves"2, which is to call them idiots just in more words, he recalls how in China he developed an electric car that, he claims, cost just €900. In how far the price is correct, we know no, but that car itself can be viewed as part Shapes of the Future where it stands as an uncommon shape of the future, a Colani shape of the future, one defined to a large degree by the round windscreen with three wiper blades that appear to rotate. A two-seater electric car which, true to Colani's approach, has been designed in fibreglass to be aerodynamic and lightweight, signature aspects of Colani's design approach complimented by the actual Colani signature on the windscreen; and a lightweight, allegedly low-price, two seater electric car Colani designed in 1995 in which context he bemoaned in 2009, "when you see all the idiots sitting in car factories they are building into their one-tonne or one-and-a-half tonne metal boxes an additional electric or hybrid engine and they think they've invented the new era, these idiots"3. And while you can't agree with his language, as you look at a global car industry in 2025 where electric cars can weigh up to two tons, did he have point in 1995? 4

Or his opinion that the automotive industry, "haven't understood at all, what it means to transport two people from A to B in the cheapest way possible"5. Discuss. For all with the German automotive industry. And with those who think flying cars are the answer. And bikes and trams aren't.

A series of rants against the automobile industry that includes the opinion that "the renaissance of other, the rebirth of other, drive technologies, electric, hybrid, whatever, solar, requires its own design language".6 An opinion, we'll argue a truism, to which we'll add, '... and new materials'; the interplay between materials and forms being paramount in the developments that drive, pun intended, human society and all its objects of daily use; that point that was and is also underscored and reinforced by Science Fiction Design: From Space Age to Metaverse at the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Weil am Rhein, in context of furniture with its elucidations on how the novel materials of the post 1939-45 War decades enabled designers to experiment with novel forms for furniture, empowered designers to argue for their furniture shapes of the future, to allow furniture, relationships with furniture and the function of furniture to keep pace with and contribute to contemporary and future society.

Designers including Luigi Colani.

An aspect of the Colani cannon explored in Marta Herford via a selection of Colani's designs, positions and arguments, a selection, if one so will, of his philosophies, starting chronologically with two objects from his 1965 Meereskollektion, Maritime Collection, for Kusch+Co, works in rubber foam that are as much about exploring the possibilities of that novel late 1960s material as they are seating solutions, and works that for all they resemble previously unknown inhabitants of the deepest regions of the ocean, and the freehand sweeping curves of an uninhibited expressionist, are forms very closely aligned with the sweeping curves of the human body and the positions that body naturally takes at rest. Indeed we'd argue there are very much echoes in Colani's Meereskollektion of the seating and lounger designs a Willy Guhl developed in the 1940s and 50s through experimentation and observation with and on the human body, an empirical approach, rather than Colani's more speculative, artistic approach. Whereby we're not sure if Luigi Colani would approve of us making such a comparison. We've done it nonetheless. Not least because its a comparison with a Willy Guhl that allows for easy access to appreciations of the Meereskollektion as an attempt to reduce resistance in seating to allow for a more economic sitting experience, much as the sweeping curves of the Colani Truck or Shanghai electric car are about reducing wind resistance to enable more economic transportation.

An approach to furniture design that can also be followed and appreciated in many of Colani's other furniture shapes of the future on show in Shapes of the Future, including, for example, the 1968 Poly-COR chair for COR, that implied and feigned Möbius loop that rounds, softens and opens Eero Saarinen's decade older Tulip Chair, and also plays with, functionalises, the sculptural forms of a Max Bill, which may or may not have been deliberate; a 1967 plastic garden chair, a monobloc from the earliest days of plastic monoblocs, for Essmann KG, that features a formed seat and backrest by way of aiding seating comfort, a comfort, one images, further aided by a, one presumes, resilient connection between seat and backrest; two variants of the Sadima lounge chair developed with and for BASF in 1970, one of which resembles a luge hurtling down an alpine ice canal, or more accurately an ergonomically formed luge, a luge if Colani had designed it, which bring us back to his 1985 bobsleigh; or a 1973 sofa for Fritz Hansen that for all it screams early 1970s at you, and in many regards stands in Marta Herford pining for an early 1970s it never wanted to leave, does also suggest novel approaches to sofa construction, use and design. And enables a fascinating and instructive detour to Arne Jacobsen, one we'll leave you all to make on your own.

While beyond conventional seating, or at least as conventional as a Luigi Colani did seating, Shapes of the Future also introduces, for example, the so-called Pool seating landscape from 1970 for Philip Rosenthal, a mix of carpeting and seating that filled a room as furniture rather than adding carpeting and seating to a room, a work as decadent as it is utilitarian, as with so much of the Colani canon; his late 1960s Elmar desk and his untitled desk chair for Flötotto, the latter of which can, must, be understood as a further development by Colani of the 1940s Eames plywood children's chair, and which, we'll argue, as such is a critique by Colani on and of the Eames; or the so-called Lernei, Learning Egg, concept developed in the early 1970s with Flötotto, a room-in-room concept in which a child could sit and study, a project that is not only physically reminiscent of the 1970s room-in-room ovular kitchen concept Colani developed for and with Poggenpohl, that Colani take on Margarete Lihotzky's Frankfurter Küche, but as a dedicated module in which children can learn with the aid of a computer technology that in 1970 was in its infancy but very much unstoppably establishing itself as the norm, also reflects the wrestling with questions of technology, efficiency, function, space, shapes, the future, that is not only embodied in the Poggenpohl concept kitchen, but, as one can better appreciate in Shapes of the Future, was at the core of a lot of Colani's work, was at the core at a lot of Colani's philosophy of form. And is at the core of the contribution a Luigi Colani can make to contemporary discourses.

And a discussion on Colani's furniture design that also features, as the law demands of any Luigi Colani exhibition, Der Zocker for Kinderlübke from 1972 and Der Colani for Top System Burkhard Lübke from 1973; two works, a work, that, not uninterestingly or uninformatively, began as Der Zocker, began as a child's seating object, before being re-developed as a seating object for adults, and which as such tends to support the argument made by and from Design for Children at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, that designing for children is an excellent, the optimal, starting point for designing for adults. And two works, a work, an ever joyous re-imagining of the Victorian reading chair, that is more an invitation to interaction than a chair; a work that while its 19th century predecessor tells you what to do and how to use it, Colani leaves that up to you. Or perhaps better put, Colani leaves all the decisions with the user, demands you make it functional, for you, in that moment, and as such openly challenges the rigidity, inflexibility, authoritarianism, inherent in conventional definitions of form follows function. And also actively questions the role of the designer.

And thus two works, a work, that allows one to better locate a lot of Luigi Colani's work in both the questioning of the tenets of Functionalist Modernism undertaken in the second half of the 20th century and also in the Art Nouveau of the late 19th/early 20th century.

A questioning of Functionalist Modernism that in the case of Luigi Colani is, as previously discussed, and as deliciously demonstrated in the trio of videos in Shapes of the Future, often undertaken in the form of rants and insults in the direction of the post 1939-45 War Functionalist Modernists who, in Colani's not so humble opinion, reduced the legacy of the Bauhauses down to the white cube and thereby ignored not only the circle and square that were also at the core of their geometric approach, but also saw them ignore, disregard, denigrate, the vivid colours, the Bauhauses were anything but monochrome. Have become monochrome and quadratic through convention and lazy repetition. Luigi Colani, in his words, sought to re-stablish the Bauhauses, to give the Bauhauses back all those things that had been take from them in 1950s and 60s, or in our words, sought to carry that which he understood as the spirit, ethos, lesson of the Bauhauses into the novel materials, novel technologies and novel social, economic, ecological et al realities of the 1970s and 80s. He did so with a truly appalling, objectionable persona, but was he correct? And was part of the resistance to him, part of his alienation from the design world, because he was correct, and in being correct directly challenged, threatened, the business models of others? Or is that us now wandering into Colani conspiracy theory territory?

A desire to re-establish the Bauhauses, to bring his understandings of the spirit, ethos, lesson of the positions of the 1920s and 30s into the second half of the 20th century that also allows one to reflect on what "Postmodern" actually means? What is "Post" and how does it relate to "Modern"? And what would Luigi Colani make of the building Frank Gehry developed for Marta Herford? Would he be happy to have his works displayed in such a space?

And an Art Nouveau that helps underscore that many of Luigi Colani's shapes of the future are and were simultaneously shapes of the past; shapes informed by sources similar to those of the Art Nouveauists, if from different motivations, in different contexts and with different material and technological possibilities, and which thus represents that further development, further thinking of Art Nouveau, that learning from Art Nouveau, that, as discussed from Reform of Life & Henry van de Velde mittendrin at the Kunstsammlungen, Chemnitz, we, inarguably, should all undertake a little more of today. Colani unquestionably advanced his further thinking of Art Nouveau with truly appalling, objectionable behavioural mannerisms, but was his method of further thinking of Art Nouveau, his appreciation of how Art Nouveau could contribute to contemporary society, correct? Was his appreciation of the spirit, ethos, lessons of Art Nouveau correct?

And a mention of a Henry van de Velde which brings us back to the so-called Werkbundstreit of 1914 and its central question as to if the shapes of the architecture and design of the future should be based on typisiert, standardised, elements all employed or on the free will of the creative in context of the project at hand. Henry van de Velde was a stout advocate of the latter, as would a Luigi Colani have been, thereby placing him very much at odds with a great many 1950s and 60s protagonists of Functionalist Modernism, which, arguably, was a large part of his problem with a HfG Ulm where standardisation, Typisierung, was wrote large. But was he correct?

For all that you may want Luigi Colani to fall flat on his face, and when viewing Shapes of the Future there are a great many occasions when that is very much your hope, was he occasionally, regularly, correct?

That the synthetic plastics that abound in Shapes of the Future, and that enabled Colani's shapes of the future, would later prove to be such a problem isn't something he could reasonably have been expected to appreciate at that time. But he was very much against the private car, for all the time and effort and money he invested in designing cars.

And for all that today he is celebrated by petrol heads. Petrol heads who've probably never read any of his texts, just seen photos of his work. An important lesson in the value of approaching the world through words not pictures. A lesson we collectively needs must learn before its too late.

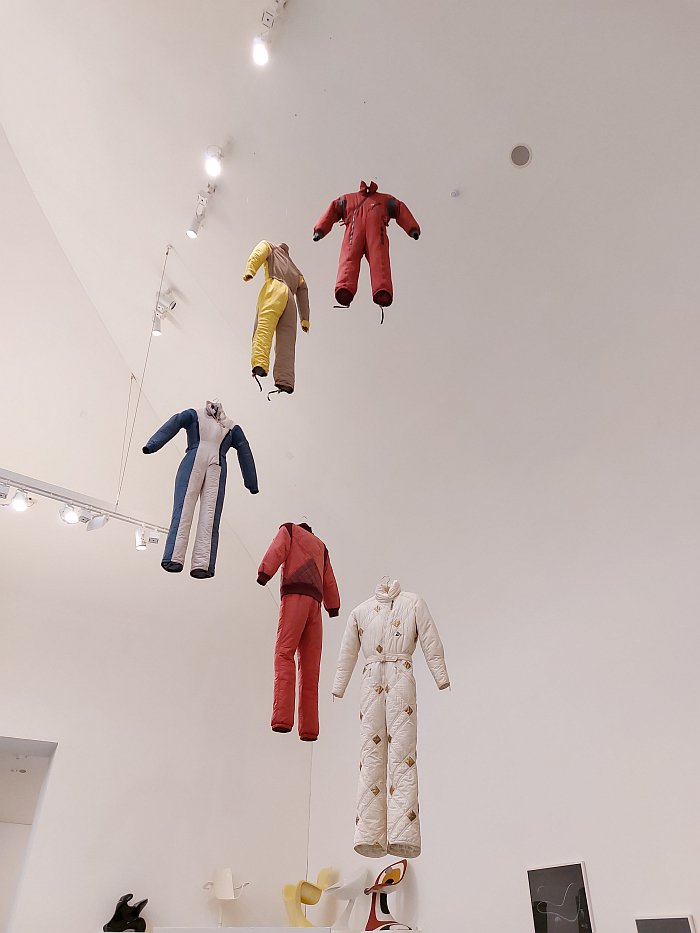

A relatively bijou exhibition, or more accurately, relatively bijou in context of the endlessness of the Colani oeuvre and catalogue raisonné, an endlessness Shapes of the Future effortlessly allows one to appreciate via a presentation that in addition to the aforementioned and discussed transportation and furniture designs includes, and amongst many other works, examples of his clothing design as exemplified by series of ski overalls from 1980 for Valmeline, his bathroom suites for Villeroy and Boch, complimented by a sketched sitting study; or his electronics designs, including works for West German manufacturer Vobis and for various Japanese manufactures such as Sony or Canon, the latter works that are also a reminder of that period in the 1980s when Colani turned his back on a West Germany in which he didn't feel appreciated. Which, yes, may have been partly his fault. But is still a moment that needs more serious reflection, questioning, challenging, that it, arguably, has had until now.

In how far he 'designed' the Colani Weiss interior wall paint for Elastolith, or in how far it is but a perfect example of the carefully constructed and cultivated Colani persona, is another question; however, as a Colani white paint it does allow for a very nice differentiation to be made between Colani and that other popular developer of shapes of the future in the second half of the 20th century, that other critic of the furniture industry in the second half of the 20th century, that other advocate of the vivid colours of 1920s and 30s Modernism the 1950s and 60s forgot, Verner Panton: where a Luigi Colani marketed white paint, a Verner Panton called for an extra tax on white paint, such was his resistance to white in interiors. And a Verner Panton who, lest we forget as we all all too often do, was active in the West German furniture industry at the same time as Colani. If less provocatively, Panton, for example, never calling on customers to boycott West German office furniture manufacturers. Whereby in his argument that the 1970s West German office furniture industry, and amongst other accusations, took customers for granted, bypassed the needs of users and ignored the reality of seating related injuries, was Colani maybe correct? Did something not need to change?

And a West Germany furniture industry that is strangely absent from the popular narrative of European furniture (hi)story, and which in being such tends to make the likes of Colani and Panton much harder to place in the (hi)story of European furniture design, denied as we all are access to a full appreciation of their contributions to the development of furniture and, importantly, the furniture industry.

Shapes of the Future is an admonishment for a closer study of that West German furniture industry, and for all of the furniture industry that was once so important for the region of Ostwestfalen-Lippe in which Marta Herford stands, and which is and was home to manufacturers such as, for example, Top System Burkhard Lübke, Kinderlübke, COR, Flötotto or Herford's own Poggenpohl, manufacturers for whom Luigi Colani was so important, and who were so important for Luigi Colani, for allowing Luigi Colani to develop and articulate his arguments and positions. Even if Colani probably wouldn't admit the latter.

It's nonetheless still true.

But for all Shapes of the Future is an admonishment, five and half years after Lutz/Luigi Colani's death in 2019 aged 91, to approach Luigi Colani afresh, now that one can without him continually popping up and commenting. Without the risk of being insulted by him.

A re-approaching, a reassessment, we'd argue, and argue that Shapes of the Future supports us in, that, for us, begins with a separation of the rants, insults and claims from the realised works; whereby, one shouldn't ignore the rants, insults and claims, nor indeed the unmistakable odour of toxic masculinity that accompanies Colani, on shouldn't pretend such aren't there, weren't part of the narrative: the persona is important. But, for us, such aspects needs must be approached separately, and that not least because they are components of the Colani character not of the Colani oeuvre they've long been confused with. The rants, insults and claims, and odour of toxic masculinity, despite how they are often presented, aren't part of the Colani catalogue raisonné. Even if they may or may not be by design rather than nature.

Which brings us, as so oft with Colani, to the question if one can like an artist despite the artist: can find an artist's work good and interesting and relevant despite rejecting that artist's objectionable character? A question a great many find themselves asking today not only in context of art, but also in context of, for example, buying an electric car or using a social media platform. ¿Is it OK? A discussion in context of which we always refer to George Orwell's 1944 essay Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali, in which he opines, "One ought to be able to hold in one's head simultaneously the two facts that Dali is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being. The one does not invalidate or, in a sense, affect the other."7 ¿Is he correct? ¿Can, should, must one extrapolate the question to a Colani? ¿Ought one be 'able to hold in one's head simultaneously the two facts that Colani is an interesting, informative, instructive, important designer and a frightfully abhorrent human being. The one does not invalidate or, in a sense, affect the other'? We'd argue yes.

And would argue it is now possible with the passage of time since his death, with the distance that death brings with it, with the silence that death brings with it; it is now possible, for all their omnipresence, to ignore the rants, insults and claims, to ignore the persona of Luigi Colani that so dominates assessment and appreciations of Luigi Colani, and to concern yourself in depth with the positions and approaches and arguments of Luigi Colani, the philosophy of form of a Luigi Colani and the reasoning that supported that philosophy.

Something Shapes of the Future assists you in, not only through the wide variety of objects and positions, presented but also through the very pleasing amount of space and time Ylem, Colani's, for want of a better term, manifesto from 1971, a collection of texts, drafts, proposals, designs, is given; one is actively encouraged to engage with the various themes therein, and which is important that you do, when surrounded by so many Colani works, as it is important in allowing one to approach a more nuanced understanding of Colani. As are the video interviews with individuals who knew and worked with Colani at various stages of his career, and in various contexts, and which tend to both confirm the Colani persona as being one and the same as Colani the man, but also provide insights into an alternative Colani, a Colani who couldn't possibly have been rants, insults, claims, a Colani free of any lingering odour of toxic masculinity, a Colani who occasionally also appears between the rants, insults and claims in the trio of videos, thereby further stimulating the questions of what was real, what was show and how, ¿did?, the relationship between the real and show shift with time?

Questions normally posed in context of the Colani persona but which Shapes of the Future encourages you to pose in context of the works Colani realised.

And while Shapes of the Future does introduce a great many works that are more on the show side of the equation, including, for example, his 2007 proposal for a new model for a planned relaunch of American automobile manufacturer Pierce-Arrow, a proposal that stands in Marta Herford as an object of purest car pornography, and as a work all to obviously informed by the Batmobiles of the 1980s and 1990s, that influence on shapes of the future through film and television discussed by and from Science Fiction Design: From Space Age to Metaverse, and also by a Luigi Colani doll, no honest, a Luigi Colani doll fom 2009 that can hang out with your Barbie's and that is playing painfully with the Colani stereotype, while also encouraging the worst aspects of that stereotype; yet while such works of show are there, the great majority of the works presented in Shapes of the Future have an honesty, an integrity, a decency, a desire that convinces as authentic. And that forces you to consider the degree to which they are and were correct.

Be that, for example, and in addition to many of the aforementioned works, his 1976 LTI lightweight transport concept for bicycle manufacturer Kalkhoff which aside from being a reclining bike with a cover i.e. a pedal car, contains an integrated shopping trolley attached to the back, i.e. a boot you can take shopping with you, fill up, attach and transport home; the interactive, height-adjustable, playful kids furniture for Ellerbrok; Wuppi for Top System Burkhard Lübke, a spindle on which children could stand, spin, get dizzy, and independently explore the world as a child. Or Der Zocker/Der Colani, two works, a work, we will always come back to in context of Colani. There is a reason they are legally obliged to be in any and every Lutz/Luigi Colani exhibition.8

A wide variety of works by Colani from across the decades of his career that are no only interesting and informative on their own but for all through the manner in which they relate to another, how they communicate with one another, how they all contribute to not only Colani's arguments on function, shapes, the future but to Colani's philosophy of form, of relationships between form and function that were becoming increasingly complex as society became increasingly complex; as noted above Shapes of the Future is an exhibition where you needs must keep criss-crossing your path in order to compare and contrast, there’s no straight line though through Luigi Colani's oeuvre, his work is focussed, single-minded, knows where its going, but isn't mono-directional. Which, yes, is possibly a metaphor. And a nice piece of advice.

A contribution by Colani to the physical shapes of the future that is also a contribution by Colani to the social shapes of the future, and thus a reminder that design is never about objects, that's lifestyle, t**** and commerce; design is always about relationships, about interactions, about the changes brought forth and contributed to, about society, and that while a Luigi Colani may not have felt part of the design world, he was very much part of designing the world.

A contribution to designing the world by material, tangible means and by immaterial, intangible means.

A contribution we all make.

The latter to a large degree in context of how we communicate with one another, that as a Marshall McLuhan argues, "the medium is the message" and/or "the medium is the massage". Take your pick.

Which brings us back to the rants, insults and claims, this time separated from the realised works.

Rants, insults and claims of greatness, of superiority, of being overlooked and undervalued that today is the preferred method of communication, the preferred medium, of a great many politicians in powerful positions, individuals who posses an apparent self-confidence tinged by paranoia and narcissism, and a refusal to accept inalienable truths that don't fit to their narrative. And who are accompanied by a lingering odour of toxic masculinity. Many of whom have their own dolls. And an unhealthy fascination with their own signature. A signature they'd apply with a branding iron if they could. And which if they did would resemble a weapon rather than a tool.

Luigi Colani is and was a designer for today, a designer who would have flourished in the toxicity and fantasy and self-flattery of social media, a designer ahead of his time in terms of persona and presentation as much as in terms of the works he realised. No questions.

Viewing Shapes of the Future is however to critically question Colani's persona, to not to blithely accept it as has been the case for so long, Colani ¯\_(ツ)_/¯, but to question Colani's persona, to question Colani's persona in context of the all too obvious contradictions and repudiations that exist between that persona and his works, to question the society of his persona and the society of his works, to question Colani's persona in context of today, and for all to question where such a persona, where such forms of communication and interaction take us, how does such behaviour affect us, how does tolerating such behaviour affect us, how does such behaviour affect the shape of future society? What's the message? What's the massage?

What does the philosophy of social form tell us?

Arguably that, as Luigi Colani's philosophy of physical form tells us, alternatives are possible, more often that not desirable, certainly worth exploring, that resistance is an important, integral, component of forward motion, an important check on forward motion, and that the most meaningful results require an open and honest approaching of the problems as they actually exist in contemporary contexts, informed by the past while never recreating the past in now, and free of convention, dogma and formalism.

Get that right, and the future will have, and be in, meaningful shapes.

Luigi Colani - Shapes of the Future is scheduled to run at Marta Herford, Goebenstraße 2–10, 32052 Herford until Sunday March 23rd.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://marta-herford.de

1"Ich habe mit der Designwelt ja eigentlich nicht zu tun. Das was ich tue, würde ich ganz nahe an die Formphilosophie heran bewegen" Unreferenced quote in Luigi Colani - Shapes of the Future. Always reference your quotes! Even in an exhibition wall text, it's important!!

2As spoken in Luigi Colani in der Werkstatt, a series of short films of Colani at work shot by Jürg Bärtschi between 1988 and 2011. Unpublished. On constant loop in Luigi Colani - Shapes of the Future

3ibid

4Yes, a large part of the weight of electric cars is the battery, but how much of the rest of the weight is necessary and how much is 'styling' and unnecessary additionals? And how many electric cars are petrol cars with an electric motor?

5As spoken in Luigi Colani in der Werkstatt, a series of short films of Colani at work shot by Jürg Bärtschi between 1988 and 2011. Unpublished. On constant loop in Luigi Colani - Shapes of the Future

6ibid

7George Orwell, Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali, The Saturday Book for 1944, London, 1944 reprinted in George Orwell. Essays, Penguin Books, 2000 page 253

8There is no legal requirement. We made that up. Sorry. But it is important that they are always present in any Luigi Colani exhibition.