Once upon a time in a land far, far away there was cafe called Pasaka, Fairy Tale, a cafe designed for children.

With the exhibition Fairy Tale. Childhood in Lithuania during the late Soviet era Kaunas Picture Gallery take that cafe Pasaka as the starting point for a multi-disciplinary exploration of the degree to which childhood in the Lithuania of the 1960s, 70s and 80s outwith cafe Pasaka was of the joyful fairy tale type, a land of magic, plenty, positivity, and dreams coming true and/or was more the darker, forbidding, foreboding type of fairy tale.......

Opened in downtown Kaunas in 1960, and expanded in 1969, Pasaka was the first of several children’s cafes across Lithuania, the first of several children’s cafes across the lands of the former Soviet Union, to open in the 1960s and 70s and 80s; a space in Kaunas we personally never experienced, but which to judge by the films and photos on show in Fairy Tale. Childhood in Lithuania during the late Soviet era, not only provided child sized furniture and child friendly food and drink, including the very exotic sounding Senjoras Pomidoras, Señor Tomato, a tomato juice based kids cocktail, all served not by waitresses but by Pasakų Karalaitės, Fairy Tale Queens, but a space that was dominated, physically and conceptually, by its four triangular stained glass windows.

Four stained glass windows created in context of the 1969 expansion by Filomena Ušinskaitė, an interesting and informative creative in 20th century Lithuania, a scion of an interesting and informative family of Lithuanian artists, and inspired by Salomėja Nėris' late 1930s children's poem Senelės pasakos, Grandma's Tales, a poem from a Lithuania prior to that under discussion in Fairy Tale, but no less interesting a Lithuania; and a poem that in referring to countless traditional Lithuanian fairy tales and folk tales not only celebrates those tales, but seeks to motivate children to engage with the characters, motifs, mottos of the those tales. Or at least does until Grandma falls asleep. Four stained glass windows that specifically expressed Ušinskaitė's depiction of Eglė Žalčių Karalienė, Eglė, Queen of snakes, the torment and ordeals of the young orphan Sigutė, and a wolf, a bear and a trio of dwarves asleep, the latter encased in a snowdrift surrounded by "Aukso žuvys po ledu", 'Goldfish under the ice', that we are currently unable to locate in Lithuanian folkloric but which are established and familiar motifs and characters in all European folkloric, as are Queens of snakes and the torment and ordeals of young orphans. A reminder of the universality of the (allegedly) so very different cultures that form contemporary Europe.

Queens, orphans, wolves, bears and dwarves whose depictions in Ušinskaitė's stained glass and ubiquity in pan-European folkloric also offer diverting thoughts on the relationships between not only fairy tales and religious tales, but between fairy tales and the tales of heroism and patriotism by a nation's men and women in times past, distant or near past, also in terms of their function, including their figurative, allegorical, function.

Four triangular stained glass windows that are one of the first exhibits one meets in Fairy Tale as part of a wider introduction to cafe Pasaka, an introduction whose films and photos of the interior also indicate that the tables were constructed as an adult height table with child height tables attached to the sides attended by child height chairs; a constellation that poses the important question as to if cafe Pasaka's furniture was child friendly, child empowering, in that it responded to a child's scale and sense of independence, or if the construction, the design, reinforced the child as subservient to, under the control of, adults? An introduction to cafe Pasaka juxtaposed on Kaunas Picture Gallery's lower ground floor space with Squares and Playgrounds, a collection of physical objects from and photographs of those universal urban spaces either designed for children or that children traditionally inhabit and make their own; a discussion that brings forth the fascinating argument that across the former, so-called, 'Soviet Block', not only was all children's playground furniture the same, as centrally defined as so much of that era, but that it was primarily designed by female architects and designers as they were excluded from public planning projects considered more important.1 Which aside from questions of what is important in terms of public planning projects, and why are children not considered important, and also questions of gender relationships in the gender neutral 'Soviet Block', also poses interesting questions on the role and function of children's playground equipment, globally, then and now. Which also enables a deeper questioning of the role and function of children's fairy tales, then and now, initiated by Ušinskaitė's stained glass windows.

And a juxtaposition of cafe Pasaka, and its fairy tales frozen in stained glass like goldfish in ice, with squares and playgrounds as alternative spaces for children in the urban sprawl, that form Fairy Tale's opening chapter Duality of Memory, a chapter whose reflections on the forming, maintenance and reliability of memory, in many regards, echoes throughout Fairy Tale.

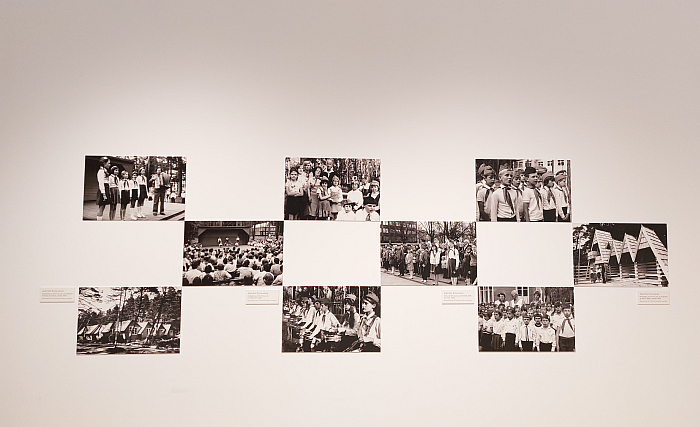

Having left the safety of cafe Pasaka via the complex, intimidating if also empowering environment of the square and playground, Fairy Tale moves on to the chapter The March of Discipline and its exploration of two existences of children in the Lithuania of its focus: the child physical and the child social. The former explored and discussed via, for example, the maternity ward, the utensils of toddlers and pre-school children, or how Benjamin Spock's 1946 book The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, that standard work of childrearing in the North America and western Europe of the second half of the 20th century, inadvertently supported Soviet propaganda in its denouncement of comics, a denouncement instructive in context of contemporary discourses on children and phones and tablets; the latter via, for example, reflections on school life, the toys of older children, including, invariably, weapons of various types and space paraphernalia of various types or the Pioneers, that ubiquitous Soviet era Communist party youth organisation.

An exploration of and discussion on The March of Discipline staged, as one learns, in a circular space that simulates the circular routes through schools Lithuanian children had to walk during breaks under the watchful eyes of teachers, a daily component of the march of discipline.

And two existences of children in the Lithuania of the period under discussion that serve as components of an exploration of and discussion on how the state sought to form the child from an incomplete adult into an upstanding member of society. A task the state saw as being its alone. A position which for all Fairy Tale's focus is without question the Lithuanian SSR of the 1960s, 70s and 80s opens up all manner of contemporary perspectives, not least in context of the reality of today's geopolitical landscape, and not necessarily only in those authoritarian nations. While for our part viewing The March of Discipline we had Tom Paxton's 1964 song What did you learn in school today? as a contemporaneous earworm to the pictures of youthful Pioneers et al. A song that regularly invades our brains these days, much more regularly than we'd like it to.

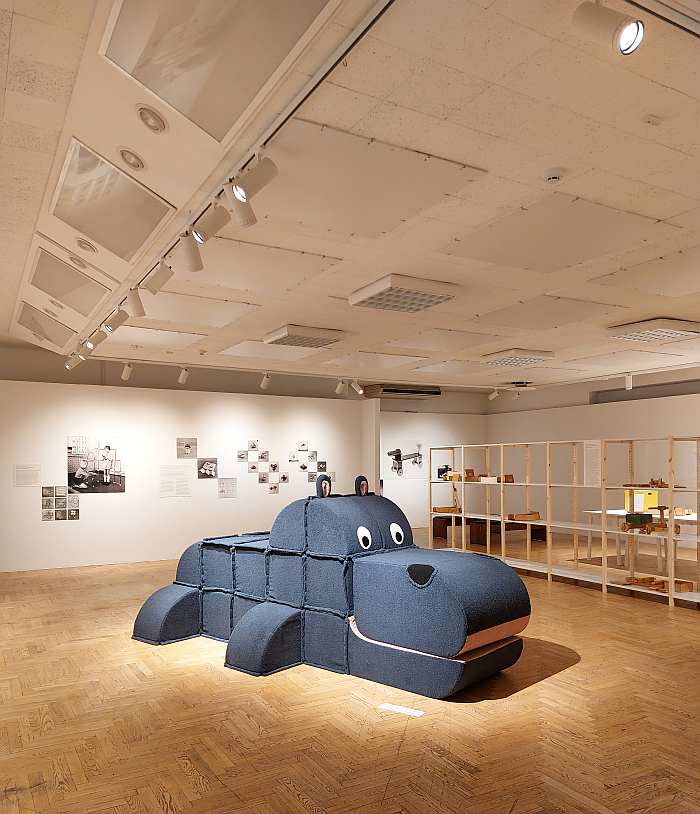

A forming of the child by the state into an adult of the state that is juxtaposed in Fairy Tale's final chapter by a third existence of children: Child as Freedom. A chapter that approaches the child as freedom through a gallery of children as depicted in Lithuanian painting and photography of the period under discussion, including a presentation of pages from family Zubov's album of drawings, sketches, paintings by and of the family's children, private memories of a period of collective memory; an exploration of toy design in the Lithuania of the period under discussion, including, and amongst other examples, Kristina Pumputytė's plastic straw based construction set that allowed children to develop their own structures, environments, or would have had it moved beyond a prototype, or a family of foam toys by Natalija Andriuščenko that similarly never entered production; toys that thus can't form part of the memory of the Lithuania under discussion but which do enable wider perspectives on the (hi)story of design, design education and the relationships between design and industry in Lithuania, and thereby help reinforce that important difference between what was and what we remember was. And by a monumental hippopotamus that is as much a furniture object as it is plaything, designed by Natalija Andriuščenko along with Vita Kašėtaitė-Čaplikienė and Regina Pakstaitė, that definitely was produced, if only once, and which finds an echo in Alexandra Kiesel's monumental leather rhinoceros Clara who one meets in Design for Children at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, an exhibition that serves as an excellent conversation partner with Fairy Tale at a number of levels.

And a child as freedom also approached through an exploration of children's literature in the Lithuania of the period under discussion, an exploration staged in what the curators refer to as the Fairy Tale Alphabet that physically very much resembles the enchanted forest that is such a staple feature of the fairy tale: an enchanted forest populated by letters including Č for Čir vir vir pavasaris Kazys Grigas's playful 1971 collection of Lithuanian proverbs, idioms and peculiarities, M for Miško pasaka Eduardas Mieželaitis adventures of the young Medinukas, T for the planet Tandadrika of Vytautė Žilinskaitė's 1984 tale Kelionė į Tandadriką, Trip to Tandadrika. Or K for Knyga, Book, with its concise reflections from 1982 on the reality of books, bookselling and publishing in Lithuania by one Algirdas Žukauskas.

A child as freedom that also tends to imply childhood as a freedom for adults through providing escape, a not irrelevant perspective on the relationships between the world of the adult and the world of the child and the very real need for adults to remain connected to that of the child for a myriad reasons.

If a child as freedom that sits very uneasily with the child as formed by the state, as an object of a centrally defined society, as approached on the floor below, an unease, arguably, echoed in the way the tables at cafe Pasaka allowed a child to sit uneasily between freedom and discipline; an unease reinforced by the thoughts from the opening chapter on the parable nature of fairy tales, of the figurative form and function of fairy tale-esque narratives, stories, in religious and identity contexts, and by the questions of the forming, maintenance and reliability of memory that echo through Fairy Tale.

If an unease in the relationships between freedom and discipline that challenges you to delve deeper into the themes, arguments and presented works by way of better approaching not only the Childhood in Lithuania during the late Soviet era discussed and explored, but by extrapolation global childhood then, since, now and future.

An unease that challenges you to delve deeper into childhood as a fairy tale and the fairy tale of childhood.

A discussion, exploration, challenge and extrapolation aided and abetted by the number of artistic installations that accompany the academic explorations, including, for example, Marijonas Baranauskas' and Jonas Amreaska's photos from hospital delivery rooms capturing the brutality, pain, joy of the moment we all enter this world, brutality, pain and joy that are often components of fairy tales and that, definitely, will accompany us on our journey through the world; the sound installation Game by Karolis Lasys that reminds of that other aspect of childhood, that other aspect of memory, sound, a component of and any and every environment that, as opined from Sound Sources. Everything is Music! at the Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt, we're much less consciously aware of changes in than we are of visual changes, if a change that is just as important. As are the smells, another sensory memory, another component of any and every environment, one particularly strong in context of a cafe, but which is absent from Fairy Tale. Invariably because no-one thought fit to archive the smells of cafe Pasaka. Or what may or may not be called Naptime by Robertas Čerškus, the signage wasn't that clear, but that is and was a joyously jaundiced yellow installation reflecting on the institution of the sleeping child, if one so will a fourth existence of children, via the medium of the pillow. And a discussion on the sleeping child staged not uninterestingly next to, in dialogue with, a discussion on orphans in the Lithuania under discussion, a child fully exposed to the state without the protection of a family that offered a freedom from the discipline. Or at least could do.

And a discussion and exploration also undertaken in the company of the voices of some of those who were children in the Lithuania under discussion, the voices of those who were the intended users of the playground equipment, crockery, Pioneer hats, toys, books et al on show. Voices that talk of how kindergarten children had their own personal cloth for cleaning the institution's toys and plants, talk of how children who didn't sleep during the regulation kindergarten sleep break had to do 10 squats, talk of sewing and knitting clothes for dolls, of climbing trees, of chewing gum from Poland, of self made "chewing gum" that one claimed came from America, of a father's anger at a red five-pointed star Spaliukų ženkliuke, October badge, that marked a 6 year old child's, unknowing, unconsenting, entry into the Communist Party. Voices that form a component of the primary discussion and exploration of Fairy Tale but also the various secondary discussions and explorations, including memory. Including memories of the battles between kids from neighbouring backyards recalled by a couple of voices; a memory depicted, captured, in a large format photo in Squares and Playgrounds.

Thus voices that provide a very nice third perspective beyond that of that academic and the artist via which to approach not only the childhood in the Lithuania under discussion, but global childhood more generally. And of our universality that we employ to define our differences.

If voices regrettably only in Lithuanian. As are the discussions on children's literature in Fairy Tale Alphabet. Yes, they are all printed and so with the aid of a translation app non-Lithunaian speakers can read them, but that's a slow tiresome process, and there are a lot of such texts, and thus, for us, very much a structural, contentual, weakness of an otherwise bilingual Lithuanian/English presentation.

A bilingual Lithuanian/English presentation that otherwise very satisfyingly starts in Kaunas then takes you far, far away from Kaunas, but always back to Kaunas. Before taking you far, far away again.

A Kaunas where one meets the stelae Peace by Robertas Antinis that once stood in the city's Vienybės Square, in dialogue with the Lenin monument that dominated the Soviet era Vienybės Square, a stelae that survived the original post-1990 spatial reconstruction but fell victim to a later spatial reconstruction and that takes you far, far away from Kaunas to questions on how and why urban spaces change and how spatial changes impact on not just memory but the lessons of the past spaces can teach us, an important component of the relationships between architecture and society; a Kaunas where one enters the primary and secondary classrooms of the city's Soviet-era schools, institutions whose curriculum was defined and managed, as across the USSR, centrally by the Russian SFSR, and which takes you far, far away from Kaunas, ideally in company of the 2022 Bauhaus Lab, Doors of Learning. Microcosms of a Future South Africa as presented at the Bauhaus Building, Dessau, to reflections of the ease with which education can be misused as a political conditioning tool, "What did you learn in school today dear little boy of mine?, What did you learn in school today....." While the ever present Russian language is a reminder of the power of language in shaping a child, shaping a future society, a reminder, certainly in a Russian context, we barely need today, but that it is good to face in such an uncompromising context.

Or to the communal courtyards of Kaunas where a mysterious character known as Žaislų Daktaras, the Toy Doctor, would pass through in the dark of night collecting broken and damaged toys as he/she/it passed, before repairing and returning them. A Žaislų Daktaras that is not the character of a fairy tale but was an actual individual, and who can be reflected on in Fairy Tale via an installation by Martyna Plioplytė-Zujienė. And a Žaislų Daktaras who through sounding like a Social Design Masters project one wouldn’t be surprised to meet at a contemporary design school, takes you far, far away from Kaunas and reminds that some people are just nice, there always were nice people, and if more people today were nice we wouldn't need Social Design, wouldn't need external tools to enforce niceness on a society that cares ever less about others and ever more about itself.

A society in which anyone collecting broken toys in communal courtyards in order to repair them is likely to be arrested or attacked by social media vigilantes.

A reminder that Fairy Tale is a view on a society that no longer exists, or at least no longer exists in the same contexts and realities. But does still exist in the fact that those who were children in the period under discussion and investigation, and in the years immediately following that period, have since that childhood worked, or not, at all levels and contexts in establishing a contemporary Lithuania so far removed from the Lithuania of their childhood, and thus enables reflections on the endlessness of society, that society is not only much longer than politics but much deeper and much robuster. A very important consideration these days.

And also still exists in the reflections and considerations it enables and empowers on the relationships between childhood and society, on childhood as a component of society, a space within society, arguably the first of many we occupy; thoughts that are also one of the myriad previously noted dialogues between Fairy Tale and Design for Children and that also provide an alternative context to reflect on Retrotopia. Design for Socialist Spaces at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin.

Reflections and considerations on the relationships between childhood and society, of childhood as a space, that remind that our social spaces are designed every bit as much as our physical spaces, that the social space of 1960s Kaunas was designed every bit as much as cafe Pasaka with its Pasakų Karalaitės, Senjoras Pomidoras and its fairy tales frozen in stained glass like goldfish in ice, and that not only the deliberate design influences the agency of the space on the user and of user on space, but also the non-deliberate, the unplanned, undesigned; reminds of the importance of a Lucius Burckhardt's unsichtbar, unseen, design that exists in any space, environment, society.

Reflections and considerations on the relationships between childhood and society, of childhood as a space, which also helps Fairy Tale highlight and reinforce the importance of childhood in the process of us becoming adults, and by extrapolation the importance of childhood in shaping future society, to question what arises from individuals raised in a fantasy free beige world devoid of the taste of self made "chewing gum"; and also highlights and reinforces that childhood is an easily damaged space, an easily damaged good, with all the consequences that inevitably brings with it. And of the responsibility of us all to protect it, exactly as we would want our own childhood protected.

Thus enabling Fairy Tale to not only allow access to differentiated reflections on, access to differentiated memories of, a moment in Lithuania (hi)story for both those who experienced it and for those who didn't, be they Lithuanian or otherwise, nor only to allow access to differentiated reflections on memory, on the forming, maintenance and reliability of memory, the function of memory both individual and collective, on the future of memory, the future function of memory, but that also enables Fairy Tale to take an unromanticised view on childhood outwith the constraints of the 1960s Kaunas in which it opens, an unromanticised view on childhood global childhood in and since the 1960s, a view of childhood in all is facets and contexts and stages and existences, from childhood as lived to childhood as remembered and on to visions of future childhood; a Fairy Tale that very much isn't a parable but does contain not only the figurative and allegorical regularly found in parables but also the warnings, admonishments regularly found in parables. But without the biases, preaching and conditioning, the romanticism, of religious and national identity parables.

And for all is a Fairy Tale that reminds that Once upon a time in a land far, far away... is invariably also Right here, right now...

Fairy Tale. Childhood in Lithuania during the late Soviet era is scheduled to run Kaunas Picture Gallery, Namas K. Donelaičio gatvė 16, 44213 Kaunas until Sunday July 27th.

Further information can be found at https://ciurlionis.lt/kaunas-picture-gallery

1Argument appears based on Ieva Daujotaite's 2023 Master's thesis at the Royal Academy of Art London, Children's Playgrounds: The social production of communism in Soviet Lithuania 1944-1990. We've been unable to find a copy, but appears worth tracking down should you wish to better engage with the argument.