Much as design is a child of the late 19th/early 20th century so to is childhood, or perhaps more accurately so to is childhood as it is understood today.

With the exhibtion Design for Children the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, explore the relationships between design, children and childhood over the century and a bit of their co-existence.......

For all that childhood is an unavoidable phase of every human life, over a great many centuries its was, certainly for the greater majority of children, a phase without the schooling, the playing, the freedom, the health care, the protections it is today. Or that it without question should be today.

A contemporary (European) childhood, a contemporary (European) society, that in many regards has its origins in, and is a consequence of, the rise in the late-19th century of the myriad (European) Reform movements who began questioning the basis of (European) society and suggesting and demanding alternatives. Reform movements as closely associated with the industrialisation and globalisation of the period, as much a response to the realities of the industrialisation and globalisation of the period, as the myriad dialects of Art Nouveau that also arose at that time and which gave rise to design as a practice distinct from craft and applied art.

A period at the turn of the 19th/20th century in which Design for Children opens, and that in many regards in Dresden where in September 1901 Germany's first Kunsterziehungstag, Art Education Symposium, was held, an event motivated by positions that, as the organisers opined, "the artistic sense and artistic power of our people can only be inherited if we awaken the artistic talents of future generations and develop them within the possible limits", whereby as they emphasised, "we do not want to educate artists or art connoisseurs, but rather open the eyes and hearts of our young people to genuine, healthy, German art"1; a link between art and society, of the necessity of advancing the former by way of advancing the latter, of degenerate art producing degenerate societies, and of a national component in art, of art as an identifiable and definable component of a nation, reflective of the prevailing positions amongst creatives of all hues, and all nationalities, of the period. Positions that in a great many global conservative circles still are prevailing. Dominant.

And an early 20th century Dresden where one also found both Theophil Müller's Werkstätten für deutschen Hausrat and the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst, the latter technically in the Garden City of Hellerau on the northern edge of Dresden, a Garden City that itself is and was very much an expression of the Reform movements of the age; and two manufacturers who stand amongst the earliest protagonists of and advocates for not only a reduced, rational furniture design but of authored furniture design, of the autonomy of furniture designers, as realised, and embodied, by the likes of, and amongst others, Margarete Junge or Gertrud Kleinhempel, and also early producers of Reform position orientated toys and furniture for children including the works by, and amongst others, August Geigenberger, Clara Möller-Coburg or Richard Riemerschmid one meets in Design for Children's opening chapter.

An opening chapter that also includes the ever engaging and charming articulated animal figures designed by Arno Viegelmann for Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst, Munich, works that have lost nothing, but nothing, in the century since they were devised and constructed; and an opening chapter which is the starting point for an essentially thematic journey through the (hi)story of design for children, if a thematic journey that has a very clear chronological flow, a fact, inarguably, reflective of developments in design, design approaches, design practice, design positions et al as influenced and informed by technical, material, political, economic, ecological, et al developments over the century and bit under consideration, thereby allowing Design for Children to reinforce the two way relationship between design and society.

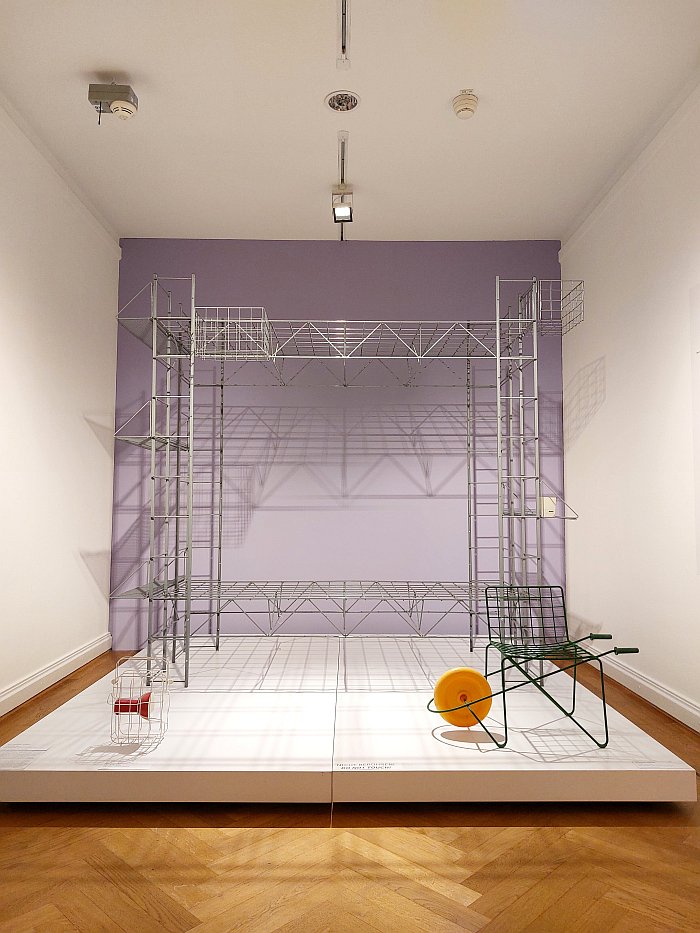

A thematic/chronological journey that along its route briefly discusses, for example, the relevance of the rise of synthetic plastics on design for children via works by the likes of Libuše Niklová, Walter Papst or Luigi Colani; the role played by construction sets be that, and amongst other examples, Friedrich Fröbel's so-called Gifts, Enzo Mari's 16 Animali, Little Toy by Charles and Ray Eames, or Karl Max Seifert's ca. 1906 garden construction set with its echos of the contemporary planning sketches of a Piet Oudolf. Or Functionalist Modernist influences on design for children including a presentation of Hans Gugelot's 1950s modular Kinderspiel-Möbel, Child's Play Furniture, system for Albin Grünzig & Co, a system that is essentially just boxes and boards that kids can arrange as their imagination and needs demand, a modular system that, as noted from Hans Gugelot. The Architecture of Design at the HfG-Archiv, Ulm, was pitched as enabling children to "build their own table, their stool, their doll's house, a shelf, a shop, a puppet theatre, all the furniture for their environment at the appropriate height and to the scale appropriate for their age"2

A system that can thus also be considered as an upscaling of a Friedrich Fröbel's or a Maria Montessori's approaches, and can also be considered as related to Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames' 1940 modular home shelving and storage system, Saarinen and Eames' Adult's Play Furniture, which similarly relied on boxes and boards that could be freely arranged, thereby helping elucidate how a single principle can have a variety of expressions and functions.

And a system, systems, that can, must, be considered as a re-imagining of Alma Siedhoff-Buscher's 1923 TI 24 system for the 1923 Haus am Horn, that first Bauhaus Weimar Show Home, and thereby not only reinforcing the influence of 1920s Functionalist Modernism as interpreted by 1940s Functionalist Modernism on 1950s Functionalist Modernism, but also the important differences between the decades.

A thematic/chronological journey with, we'll argue, the curators may disagree, but we'll argue, two primary foci: children's seating and playgrounds.

The former a focus largely discussed via objects from the collection of children's chairs assembled, accrued, by Gisela Neuwald, a collection of children's chairs from across the decades that, pleasingly, makes regularly irregular appearances in a variety of museums and contexts and which is mixed in Design for Children with works from other collections and the Bröhan's own collection. A presentation featuring works by designers as varied as, and amongst many others, Verner Panton, Egon Eiermann, Karin Mobring or Erich Dieckmann as well as numerous anonymous authors, that very satisfyingly does that thing that Gisela Neuwald's collection always does of not only reminding you that children aren't just small adults but beings with their own needs, requirements, definitions of function, their own understandings of A Chair and You, but also forcing you to question, as we noted, did, from Chairs. For children only! at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Leipzig, if it is acceptable to simply reduce chairs designed for adults down to a child's size, if children don't require chairs designed for them? That while at the beginnings of both design and childhood it was inevitable that the likes of, for example, Thonet would simply produce smaller versions of their adult chairs for children, they could do no different, that was how the world was understood then, today we have the advantages of a century and bit of reflection and consideration on design, children and childhood, have generations of experience and experimentation and iteration, and practice, have evolved and developed the form-function relationship to a complexity way beyond that which could have been comprehended in previous decades: is it still justifiable to expect children to sit on small adult chairs?

Viewing the works in Design for Children is to develop an argument that it ain't. Not even if the function of the respective chair is representation, the staging of your home. Which, we suspect, in many cases is the primary motivation of all adults concerned. Which isn't to say you can't, as several examples on show convincingly argue, you can; several work effortlessly as children's chairs, and indeed some of the children's versions make more sense, are more meaningful, than the adult versions. But they are very much in the minority. The vast majority construct a convincing argument that sitting children on small adult chairs isn't justifiable.

Thus a viewing of a vast number of chairs for children that tends to reinforce that design for children is a demand, a necessity, a responsibility, rather than a genre.

The latter very pleasingly taking considerations on, discussions on, the design for children of the exhibition title out of the home, the classroom, the interior, where it is normally located and into the spatial design of the exterior in which we all also exist. Playgrounds that are not only about play but about social and personal development, learning to interact and engage with others in their endlessness of variety; playground equipment, playground furniture, that is, in many regards, analogous to office furniture for adults, being as it is the tools you need to allow you to get the most out of your time in the wider world between breakfast and bed. But playground equipment/furniture that needs must also be fun. Has complex functional demands that are often indirect, to be determined and developed by the user not supplied by the designer. A realisation stimulated by Design for Children which, yes, does allow one to reflect on the design of office furniture, reflections given more impetus by the presence in the children's chair chapter of Peter Opsvik's Tripp Trapp high-chair, and the comparison one naturally makes to his office furniture; and the question that allows one to pose if design for children isn't a good basis for design for adults, isn't where design for adults should start? We're fairly certain many of the designers featured in Design for Children would agree it is. And that despite the varying pigeonholes convention lazily assigns them to.

A focus on playgrounds in Design for Children that is primarily the playground design and playground equipment, playground furniture, design of Günter Beltzig, a designer who is commonly reduced in discussions on the (hi)story of design to a single moulded polyester chair, an adult chair one notes, but who, as one learns and appreciates from the examples of his work presented in Design for Children, was so much more, and, as one also learns, wasn't just a playground designer but a committed protagonist and activist for playgrounds, and in being such also greatly contributed to the development of definitions of design for children, of function in terms of design for children, of arguments that design for children is a demand, a necessity, a responsibility, rather than a genre.

A focus on playgrounds the curators very satisfyingly locate in Berlin, including mapping where examples of Beltzig's designs can be found in the German capital, and thereby encouraging you to get out and explore the works in situ, and in the hands of children not of museum curators and custodians.

And a focus on playgrounds that is also one of the clearest expressions of the exhibition design concept: the slide and roundabout by Günter Beltzig on display in Design for Children can be used. By children. As can several of the chairs, Libuše Niklová's inflatable giraffe and numerous other interactive elements. In addition the exhibition rooms are richly populated with steps to allow the smallest of visitors to get up close with exhibits. Design for Children is an exhibition Designed for Children.

A design concept that does mean there are an awful lot of large 'Do Not Touch' signs scattered throughout the exhibition rooms by way of visualising borders that may not be obvious to all, certainly not to any Children of the title visiting. In which context, as we were leaving a gaggle of pre-schoolers waddled in. Yes, we were very glad that we got through viewing the exhibition before they came; and, yes, we were very glad they came, because for all that much of what Design For Children discusses and many of the reflections it initiates is and are for Adults rather than for Children, the only way an adult can tell if a design for children is really for children is through observing how, if, children interact with it. And also because the younger we all learn that museums are palaces of fun, and not dull, dark, dusty spaces that suck the joy from life, the better.

And, no, we didn't have a go on the roundabout... but we did think about it. And very much wanted to. We suspect the pre-schoolers did. We very much hope they did, it was after all designed for them, designed for their needs, for their demands, for their development, for their fun, for their world.

No, they won't remember being on it in years to come, but, in comparison to adult toys, the aim isn't, and never was, creating memories, isn't and never was about the selfish individual but about the collective.

A sprightly presentation that skips quickly on from theme to theme, which isn't a criticism but an observation, and a reality largely enforced on the curators on account of the vastness of the exhibition's scope; it can be but an introduction to the myriad subjects at hand rather than a deep analysis, a digging to depths that in many regards is for you to undertake on your own after visiting. Or for other exhibitions to take up and focus in on, the implication of half-a-dozen, or more, possible exhibitions is very present throughout Design for Children.

An exhibition that pleasingly does that thing Bröhan Museum exhibitions so often do of both allowing creatives who are normally excluded from design discourses to have their say, including several from the east of continental Europe, and also allowing creatives who are regularly featured to contribute with lesser seen, heard, works, Günter Beltzig being the clearest example, but in no sense the only one; an exhibition that is very much, as implied above, Eurocentric, the children and childhood and (hi)story it explores and discusses are European, which while understandable, defensible, in context of the limitations of time and space, is also regrettable and certainly something to be aware of while viewing. Although that said under the title 'Your toy in the museum' the curators invite all to submit a toy to be displayed, which may be an opportunity to expand the discussion beyond Europe's borders. We have nothing to contribute, but if you do.... An exhibition that through discussing design for children as being about, and amongst other concepts, play, development, comfort, security, community, individuality not only helps reinforce design for children as a demand, a necessity, a responsibility, rather than a genre, but also allows one to approach a clear distinction between design and the giddy empty rush of lifestyle and t****. A distinction between design and Instagram also highlighted by the lack of beige.

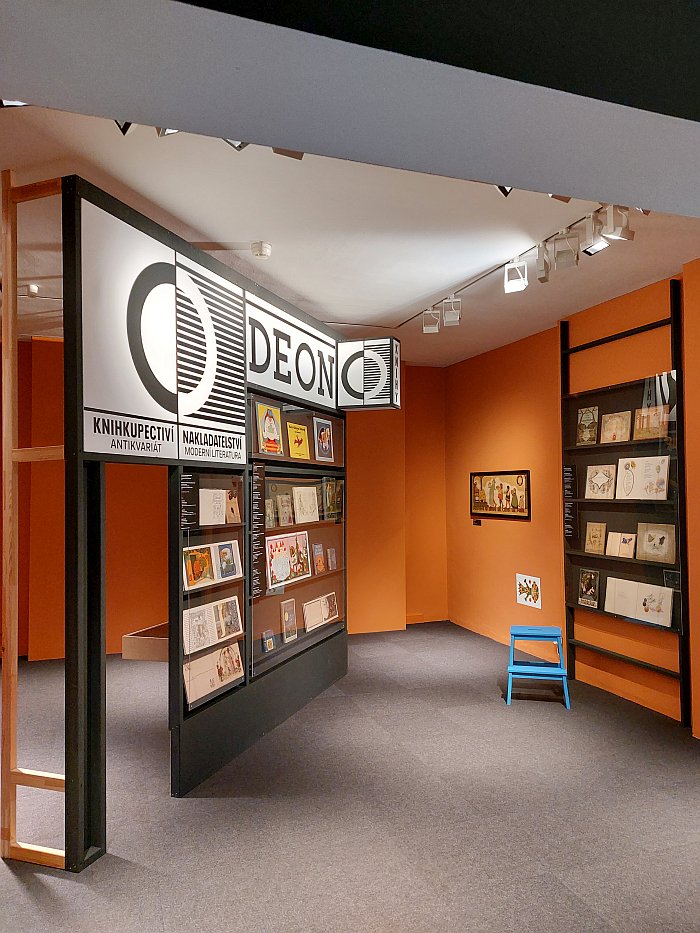

An exhibition that also includes a chapter on book design, a chapter that very pleasingly reuses the reconstruction of the display window of the former Odeon bookshop in Prague that featured in the Bröhan Museum's exhibition Hej rup! The Czech Avant-Garde, albeit with the examples of 1920s and 30s avant-garde Czechoslovakian literature replaced with books by the brothers Grimm, and other tellers of didactic folkloric. Which may or may not be a case of same same but different. A recycling of previous exhibition scenography that also exists in the frame in which a menagerie of animal creations by Renate Müller are housed alongside other multi-function objects, a frame which housed works by Peter Opsvik in the exhibition Nordic Design. The Response to the Bauhaus. Works by Peter Opsvik that are as multifunctional as the works housed in the frame in Design for Children, and which thus neatly brings one back to design for children as the basis for design for adults, to arguments that in our adult focussed viewing of the world we do ourselves a great disservice, ignorantly ignore a lot of possibilities and opportunities, discount what could be before we are aware of its existence, that we needs must more regularly approach the world as children. That design for children is also design for adults, or can be if we can learn to read it as such. And a recycling of scenography by the Bröhan Museum that is to be loudly applauded. We look forward to seeing the Odeon bookshop in future exhibitions.

A chapter on book design that also includes a library corner where children and adults can relax and read, a library corner under the librarianship of Alexandra Kiesel's monumental leather rhinoceros Clara, a librarian who exists in a nice cross-generational dialogue with Renate Müller's aforementioned menagerie downstairs; if a library corner that only features books in German....... yes, Berlin is in Germany, you're not wrong. But given that Design for Children is a bilingual German/English presentation, and that one suspects the Bröhan Museum are hoping to attract an international public, of which Berlin has very large permanent and temporary populations, one could argue, we do argue, a few books in English wouldn't go amiss.

And a chapter on books that tends to highlight that there is no computer technology to be found throughout the presentation: Design for Children is a discussion on Analogue Design for Children. Even the examples of contemporary design for children as represented by, and amongst others, Floris Hovers, Lilian Walters or Insa Decker are resolutely offline.

Which on the one hand does tend to ignore the very obvious fact that childhood today is largely lived online and that contemporary design for children is often about, and at the risk of being even more cynical than we usually are, creating online dependencies that ensure children succeed their parents as customers for digital platforms and social media concerns, contemporary realities that very much need to be explored, questioned and contextualised more than they are in public discourses, not least because of the shift such represents from design for children to design for adults used by children. See also chairs. And 18th century craft and applied arts. If design for children is a demand, a necessity, a responsibility, rather than a genre, what does it mean if increasing digitalisation means we stop designing for children and immerse them at ever early ages in design for adults, in design for the demands, necessities, functioning of adults? A discourse which one could argue, we do argue, Design for Children would be a meaningful platform for approaching.

But on the other hand the lack of computer technology very neatly and very pleasingly reinforces how the changes in society over the timespan of Design for Children's narrative have influenced, informed, changed, design, children and childhood; while superficially much of that in the final chapter could have featured in the opening chapter, it also couldn't have, society in the early 20th century wasn't in a position to develop that of the early 21st century. While early 20th century society would recognise early 21st century society, it would be unable to engage with it. Thus underscoring one of the responsibilities of design and designers, and publishers of design of all genres, to be aware of the age for which they are developing solutions for and not to simply repeat that which once was. Which yes, brings us back to the comparison between the work of a Hans Gugelot with that of an Alma Siedhoff-Buscher. And to the very real risks inherent in a popular fetishising of the objects of generations past rather than an appreciation of the whats, why and wherefores of those objects.

And also a maintenance of a taut analogue thread through the exhibition narrative which reinforces that whereas the 1901 Kunsterziehungstag was about employing art/design to shape children to what society demanded they be, today the focus is much more on the child as an independent being, an entity, on art/design as tools for the development of a child as an independent member of a society, not as a possession of a parent or of a nation. While also underscoring that then as now childhood is about learning to become an adult, be that in the home, the school, the playground, wherever, that the formative pedagogic didactic the early 20th century gave us is in design for children still an important component of design for children, but hasn't remained static. If thoughts on then and now that also lead to an appreciation that there are forces out there who would gladly see a return to art and design as central components of a perceived national identity rather than components of global discourses.

A move that as Design for Children allows one to appreciate is as impossible as returning to the design, the children and the childhood of the early 1900s.

And in doing so, in allowing for reflections on the past century and a bit of design, children and childhood, on the interactions and interplay between design, children and childhood over the past century and a bit, on design, children and childhood as components of society over the past century and a bit, Design for Children also allows ample space for reflections on how the relationships between design, children and childhood could develop in coming decades, and thereby reflections on how our society could develop in coming decades, on the question of the responsibility for that inevitable development.

And to question if after a century and a bit of design and childhood, after a century a bit of design for children, the time maybe isn't ripe for adults to give up their monopoly and embrace a world designed by children.......

Design for Children is scheduled to run at the Bröhan Museum, Schlossstraße 1a, 14059 Berlin until Sunday February 16th.

Further details, including information of the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.broehan-museum.de

1Siehe Vorwort, Kunsterziehung. Ergebnisse und Anregungen des Kunsterziehungstages in Dresden am 28. und 29. September 1901, R. Voigtländer, Leipzig, 1902 pages 7-9

2Sales catalogue, for Hans Gugelot Kinderspiel-Möbel through Albin Grünzig, Sammlung HfG-Archiv, signature unknown. As exhibited in Hans Gugelot. The Architecture of Design, HfG-Archiv Ulm 21.03.2020—31.01.2021