As previously noted, the theme of Zagreb Design Week 2024 was Breaking the Glass Ceiling, a theme that the organisers neatly, and pleasingly, expanded away from its conventional understanding in terms of gender parity and towards a demand for a design practice and design industry, or perhaps more accurately, a demand for a design practice and design industry in Europe, more inclusive that that which we currently have, while keeping a very strong focus on the gender imbalances in design practice and the design industry in Europe that still need to be highlighted and discussed, because, despite having been highlighted and discussed for quite a long time, they are still a thing. And need to stop being a thing.

A focus that included the showcase Donne Designer, a presentation supported by the Italian Embassy to Croatia as partner country of Zagreb Design Week 2024, which introduced the work of some 18 female Italian designers from across a range of genres and decades, including, for example, graphic designer Claudia Morgagni, architect and designer Gae Aulenti, glasssmith Maria Grazia Rosin, product designer Alice Rosignolo or educator Maria Montessori, the latter an early protagonist of design as being about more than products, of the responsibility of designers as being to more than industry and commerce. A claim she shares with her contemporary Louise Brigham. And which is well worth reflecting on. And a presentation that reminded, reinforced, that the popularly told narrative of design (his)tory in Italy isn't the full truth, that design in and from Italy wasn't developed and advanced by men alone, much as the showcase Buone Nuove – Women Changing Architecture at l’Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Stoccolma reminded, reinforced, that the popularly told (his)tory of architecture in and from Italy, isn't.

Nor is the (his)tory of design in Croatia the whole truth, as the showcases Dizajnerice. Female Designers: Context, Production, Influences 1930-1980 and Industrial Designers - The Fight for the Profession reminded, reinforced.

The former a project by Zagreb based collective Oaza we first came across in context of a Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 – Today at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, initiated with the aim of ensuring the contemporary visibility of female designers active in the Croatia of Yugoslavia, ensuring the voice of female designers in debates and discourses on design in and from Croatia, that resulted in an online databank. A databank whose many still to be completed entries underscore how much work is still to be done, with the obvious questions why that work needs to be done; and which was presented at Zagreb Design Week 2024 as a poster presentation introducing creatives such as, for example, Antoljak Slava, Šribar Marta, Kučinac Blaženka or Berger Otto.

The latter an, if one so will, extension of Dizajnerice curated by Zagreb's Museum of Arts and Crafts which presented objects designed and developed in, then, Yugoslavia, by way of elucidating the difficulties faced by female industrial designers in that Yugoslavia. And thereby also helping elucidate why today design (hi)story is so often a design (his)tory.

And two Croatian focussed showcases that also helped highlight the problem of intersectionality, that position, as discussed from Regard! Art and Design by Women 1880–1940 at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, that differing forms of discrimination are cumulative, the more forms of discrimination you are subjected to the worse things are for you: that it's not a case of breaking the glass ceiling, but breaking the glass ceilings. As oft discussed in theses dispatches, and as is inherent in the notion of Breaking the Glass Ceiling, a female designer has it harder than a male designer, and long has. And as discussed, for example, from Retrotopia. Design for Socialist Spaces at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin, a designer from eastern Europe has it harder than a designer from western Europe, or has had since 1990. As a female designer from eastern Europe you have it even harder still.

Which isn't only unfair and unjust in context of the respective designers, but through the skewing of both design (hi)story and perspectives on contemporary design it causes, is bad for us all. Breaking the Glass Ceiling in all its contexts is necessary for us all.

Nor is saying such to create victims. Is to highlight and discuss contemporary realities as a component of demanding change. Look, for example, at the designer roster of any major European furniture manufacturer: count the number of males, the number of females, the number of western Europeans, the number of eastern Europeans, the number of western European females, the number of eastern European females. ¿Notice anything? ¿And when you count the Africans? ¿Or South Americans, or Asians or Antarticans? The problem isn't quality, or competence, or validity of position and approach, but how the furniture design industry ticks, and who is visible and who isn't. Glass ceilings are often opaque. Or vaingloriously mirrored.

As Zagreb Design Week 2024 more than ably demonstrated, there are both a great many contemporary designers from outwith the dominant western European male designer order producing interesting, instructive works, advancing interesting, instructive positions, and also a great many researchers and curators developing platforms for marginalised designers of generations past, to ensure that that glass ceiling, those glass ceilings must, eventually, despite resistance, break.

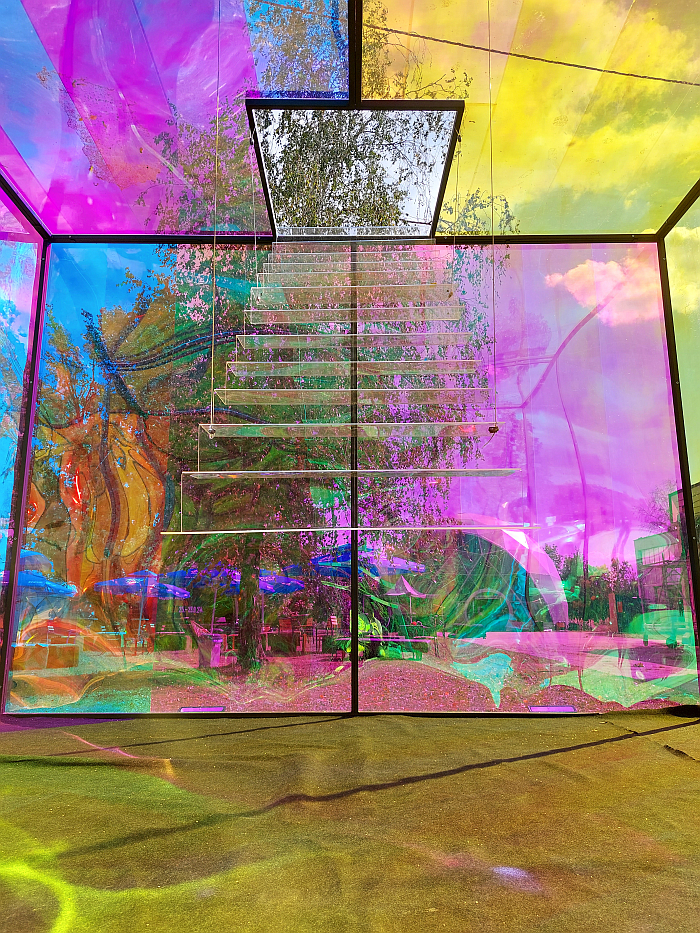

If a task whose complexity across all forms of exclusion and domination was approached by the installation Breaking the Glass Ceiling by Tina Marković and Karla Bastalić: a cube whose bling simultaneously distracts from the problem and also exists as that, as noted in context Natalia Romik. Hideouts. Architecture of Survival at the Jewish Museum, Frankfurt, shimmering facade of glitz we all cloak ourselves in by of pretending all is good, by way of denying all isn't good. Viewing Tina and Karla's cube you're so focussed on the bling, are so enjoying the bling, you initially don't see the problem. Or perhaps alternatively put, your so focussed on the colours and materials, are so enjoying the colours and materials that for so long have been the only place the design industry has allowed female creatives to occupy, and which through doing so gives the impression on first glance that there is no problem, there are lots of women in design, every manufacturer has females in their portfolio, responsible for colour and materials,🙄, you initially don't see the problem.

A cube of shimmering, distracting, bling with a door; a door that from certain perspectives scintillates in a golden hue that not only invites you in, but tends to assure you all will be OK. And so you enter, and find yourself engulfed in shimmering, distracting, bling, and thus not only essentially invisible to the outside world on account of the distractions of material and colour, but also unable to clearly see the outside world, disorientated as you are through the distractions of material and colour. By the deliberately employed bling.

But salvation is at hand, there is a staircase that leads up to gap in the ceiling through which you can escape... if that is you can get on the staircase.

It doesn't reach to the floor.

There is an insurmountable gap.

Or at least a gap insurmountable without assistance. Which is one of the problems, finding that assistance.

Over centuries men helped men, men helped men like them; you got assistance if you were not only the correct gender, but if you belonged to a particular group, alma mater, religion, skin colour, nationality etc. Or were a woman with a husband.

And today?

The greater majority of people we observed in the cube took selfies, group selfies, in front on the truncated staircase. Were perfectly at ease with the status quo, so much so they wanted to share it in the echo chamber of Instagram, share it with an echo chamber of Instagram that would delight in the shimmering bling, rather than tackle the problem of the truncated staircase.

When we were there no one saw fit to place a few concrete blocks or a small step ladder by way of negating the gap and assisting access to the stairs, and thus through the glass ceiling.

Why not?

And why did no-one see fit to replace the stairs with a ramp or a lift so that the gap in the glass ceiling was accessible to all?

And why did no-one warn their fellow visitors of the dangers of focussing on the shimmering bling? Of the dangers of letting yourself be seduced by the easy delight to be found in the shimmering bling? Of the dangers of entering the cube of shimmering bling? Why did no-one destroy it and rebuild it?

No, neither did we.

But as with a nature photographer our role isn't to intervene, our role isn't to protect the baby zebra from the cheetah bearing down on it, but is to document the moment and thus provide a context in which one can better understand the brutality, can better approach a position on and to the reality of contemporary society, and decide what, if, you can should, must do as a reaction.

Why is there an insurmountable gap at bottom of the staircase?

Whose responsibility is it to make the staircase accessible for all?

Whose responsibility is it to make the staircase a ramp accessible for all?

Why the need for the shimmering bling?

What's wrong with transparency?

Thus an installation that for all its simple, directness, was also an informative and instructive and entertaining location for reflecting on contemporary realities, for how we got to our contemporary realities, the processes that have brought us to where we are, and for stimulating questions as to how we can achieve the necessary and urgent Breaking the Glass Ceiling. On the role and responsibilities of us all in Breaking the Glass Ceiling.

Zagreb Design Week 2024 has now ended, more details on the event can be found at https://zagrebdesignweek.com