In 1991 the German, designer, theoretician, educator and co-initiator of the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, Otl Aicher, opined that "die Relation von Form und Material lässt sich nirgendwo so gut nachweisen wie bei Nahrungsmitteln, also etwa bei Teigwaren"1, 'the relationship between form and material is nowhere better demonstrated than in foodstuffs, such as pasta'.

With the exhibition al dente: Pasta & Design the HfG-Archiv, Ulm, explore not only the relationships between form and material in context of pasta, but also the wider connections between pasta and design, and in doing so enable differentiated perspectives on form, material, function, society, design and pasta.......

Mixtures of flour and water cooked to a solid mass are not only one of the oldest but one of the most ubiquitous foodstuffs, be that, for example, the noodle in its various forms, the dumpling in its various forms, the pasta in its various forms, or the spätzle in its random forms; spätzle that is so important, sacred, to the peoples of the State of Baden-Württemberg in which Ulm stands, and to the peoples of Bavaria but a spätzle ricer's throw away from the HfG-Archiv on the other side of the Danube, and spätzle which Otl Aicher once lauded as "die wirkliche Urform der Teigwaren"2, 'the original form of Teigwaren', 'the archetype of Teigwaren', to use the ever glorious German catch-all term for foodstuffs arising from flour and water cooked to a solid mass, and whose normal English translation as 'pasta' simply doesn't do it any justice.

A devotion to spätzle that tends to confirm Otl Aicher as a native of Baden-Württemberg, as an individual raised in and on spätzle; and mention of an Urform, an archetype, that, and thinking back to the HfG-Archiv's exhibition The Ulmer Hocker: Idea ─ Icon ─ Idol, tends to lead to an argument that, and with all due respect to Otl Aicher, but remembering his extremely partisan view of spätzle, remembering the caution with which one needs must approach any statement by Otl Aicher as regards spätzle.... tends to lead to an argument that in a Platonic sense spätzle is less the archetype of Teigwaren, which it in any case it can't be as it exists in the physical world, and much more that all mixtures of flour and water cooked to a solid mass are the physical approximations of the intangible archetype of food.

Tends to lead too argument that the exhibition's title could easily have been Teigwaren: Idea ─ Icon ─ Idol.

A thought the repeatedly recurs as you view al dente: Pasta & Design.

As an exhibition al dente: Pasta & Design presents its narrative in, if one so will, 6 packets, starting with From Hand to Machine, that process that all human society's goods of daily use have undergone over recent centuries and decades; a process in context of pasta that al dente helps elucidate essentially began, again as with all other goods of daily use, thereby tending to confirm pastas as a good of daily use as essential as our clothing, crockery, tools, furniture etc, in the Middle Ages, and for all in Italy; the curators debunking right at the start of the presentation the myth that Marco Polo brought the idea of pasta back from China with mention of the pasta industry on 12th century Sicily. A pasta industry on Sicily, and throughout the lands of the contemporary Italy, whose increasing sophistication and mechanisation throughout the Middle Ages as the population grew and society became ever more complex, is underscored by an 18th century engraving by Paul-Jacques Malouin of vermiceliers at work, an image that helps explain not only what a laborious job that of the vermicelier was in the earliest days of industrialised pasta production but also the technology that had to be developed in order to mass produce pasta.

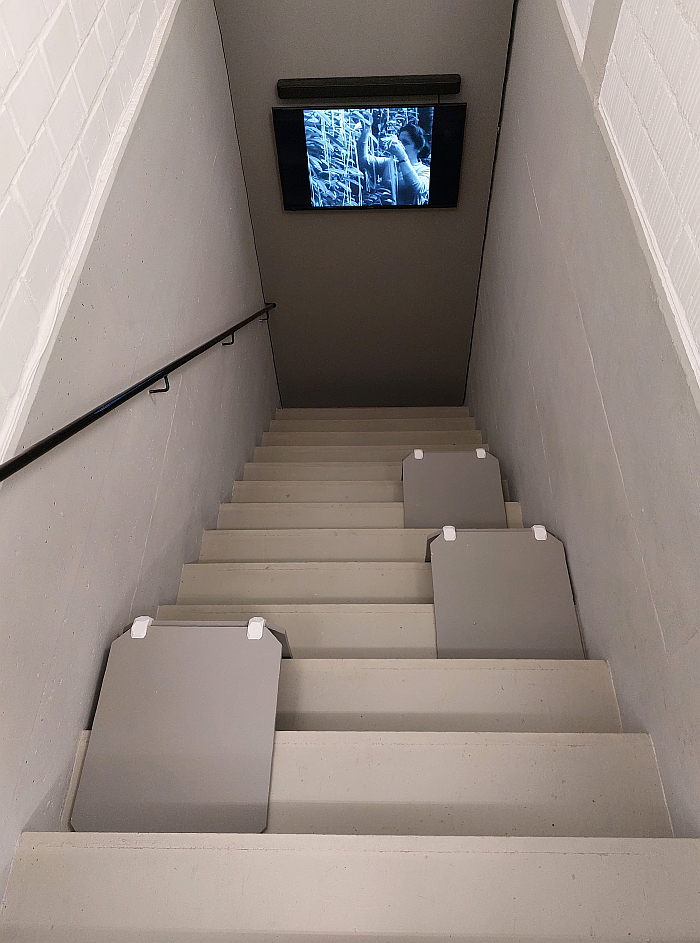

Technology such as the industrial egg cracking/opening machine, a concept, displayed in al dente as a physical object and as a video of it in action, that is as stupidly simple as it is poetically beautiful, and which poses the question who knew such was a thing. And how many other things do we not know about? Or technology such the trafile, the dies, through which pasta dough is squeezed to produce the innumerable known forms of pasta, or at least is in context of pasta produced by extrusion processes, as compared to pasta produced by rolling, such as, for example, tagliatelle and fettuccine, or those formed by hand such as, and returning to the untranslatable Teigwaren, Chinese noodles whose creation by repeatedly and rapidly stretching and folding the dough is neatly elucidated in a short video showing Noodle Master Peter Song at work; trafile that stand in al dente physically and conceptually juxtaposed to a collection of objects employed in the hand-making of pasta, including numerous variations on the home spätzle ricer, a still regularly employed tool in those regions where spätzle is sacred and ricers whose singular interpretation of the trafile, and extrusion, effortlessly explain the form of spätzle; trafile that, as can be seen in Malouin's engraving, have been employed since at least the 18th century thereby confirming them not only as a component of the industrialisation of pasta production, but the standardisation of pasta production, you'll look long and hard to find two dissimilar penne, fusilli or kritharaki in any given packet, and equally long to find two similar spätzle. And trafile that influence not only the shape of pasta but the functionality of pasta: bronze trafile, one learns, result in a somewhat rougher object that can hold more sauce, bronze trafile increasing the maximum sauce to pasta ratio, if one will increasing the efficiency of the finished pasta in context of its ability to capture sugo, certainly in contrast to the Teflon trafile that produce shiny, smooth pasta. And thus not only a very nice example of how, and as discussed in and from Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Blemishes and Defects at the Gewerbemuseum, Winterthur, striving for perfection can be counterproductive, often we need the imperfection, we often need the roughness and abrasion and serendipity, but also a reminder that in context of all manufactured goods the production process influences the quality and functionality of the end result and thus of the importance of designing the production process as diligently as the product. A thought readily extendable to architecture, urban planning and society.

Discussions on trafile, and also relationships between pasta and sauce, between form and function, between form and material, between technology and object, very much at the centre of the chapter Paths to new forms, a discussion on the role of design and designers in developing novel pasta forms including introducing the contributions of two prominent Hochschule für Gestaltung, HfG, Ulm designers: Walter Zeischegg and Otl Aicher.

The latter that so defining character not only at and of the HfG Ulm but of design in the former West Germany, and who in 1984 pitched an idea for a domestic pasta making machine to Braun, that so informative partner of the HfG Ulm; a pitch in which Aicher notes that anyone who has ever tasted home-made pasta in Italy knows how much better it tastes than industrial pasta, opining that 'it can be assumed that the production of home-made pasta will increase in popularity due to the growing quality demands on cuisine and cooking'. And he was almost right: many of us would like to make our own pasta, and every year innumerable pasta makers are bought, either by highly motivated individuals or as a gift for the foodie in your crew, and are used..... twice, thrice maximum, and then hidden at the back of a cupboard like a guilty secret. Despite us all agreeing with an Otl Aicher that home made pasta "ein delikatesse ist"3, 'is a delicacy'. Yet outwith those regions with a long tradition of pasta making, home pasta making never caught on, not even in those regions where home spätzle making is a task as regular as vacuuming: we all prefer to buy the industrial version. ¿Why? Good question. Covid could have been home pasta making's big moment. But everyone decided to start making sourdough bread. Therefore it's arguably good that Aicher's machine never saw the light of day, certainly not in the electronic version he proposed, as the waste of resources would stand in direct contradiction to Aicher's positions on sustainability and responsibility. While the fact Otl Aicher doesn't appear to have attempted to design an electronic spätzle ricer may be informative in context of Otl Aicher's appreciations of tradition and identity, not things he's normally associated with, or at least not in a supportive sense, and thus a question of why an electronic pasta machine but no electronic spätzle ricer that could be worth following up. As with the question why don't all make our own pasta. Good question.

The former, as noted from the HfG-Archiv's exhibition Plastic Material − Magic Material: Freedom and Limits of Design, an Austrian sculptor who with his sculptor's view of materials and processes was so influential in the development of the plastic workshop and design in synthetic plastics at the HfG Ulm, and who in 1962 signed what the al dente curators refer to as, 'probably the first contract for the development of novel pasta shapes between an industrial company and a designer', specifically with Mannheim based Birkel. A contract that appears to make perfect sense in context of Zeischegg's synthetic plastic research, for what is pasta dough if not a malleable material that can be freely formed, or extruded, and which on hardening becomes functional? ¿Pasta Material − Magic Material: Freedom and Limits of Design? But a contract which failed to produce the desired results; as the curators note, and as one can glean from a letter from Zeischegg to Birkel presented in al dente, industrial pasta production was too unfamiliar a terrain for Zeischegg, arguably too dissimilar from plastic art and plastic design despite the similarities; that Zeischegg, if one so will, struggled with the Freedom and Limits of Pasta, much as an Arne Jacobsen once struggled with the Freedom and Limits of Styropore, and which in context of Zeischegg is worth reflecting on in context of pasta as an autonomous domain amongst our objects of daily use. And so Zeischegg abandoned his attempts. Frustratedly so to judge by the fact he destroyed all his research.

Other designers have however been more successful in their attempts at designing pasta in the decades since Zeischegg's pioneer attempt, or at least have been temporarily, al dente introducing, for example, Giorgetto Giugiaro, that Grand Doyen of Italian car design, who in the course of a long career worked with manufacturers such as, and amongst many, many others, Alfa Romeo, Maserati, Fiat or Volkswagen for whom he designed the first VW Golf, and who in 1983 created the pasta form Marille for Voiello, a fusion of tubes and waves inspired by the rubber door seal of cars, but a Marille that is no longer in the Voiello portfolio; or Philippe Starck who in 1984, and thus at start of his career, arguably during one of the more out-of-control phases of his career, realised the form Mandala for French pasta brand Panzani, essentially a tube with a support in the middle and two wings, that is, according to Starck, impossible to overcook, an informative take on form and function in context of pasta, of function being related to the cooking and not the consumption, but a Mandala that is no longer in the Panzani portfolio. Thus two examples that tend to imply that whereas vernacular forms such as penne, fusilli or kritharaki endure, novel academic forms, forms developed from positions on solutions to challenges, invariably fade, which not only echoes realities in great many dominions of architecture and design where the vernacular prevails eternally, but is also an informative starting point for considerations on how we approach our contemporary challenges in architecture, design and society.

And is also an informative context in which to view Papiri for Barilla, a pasta form which resembles a loosely rolled sheet of paper that was developed in 2021 by Walter Maria de Silva and Mario Antonioli that is very much still in the Barilla portfolio, ¿but for how much longer? And a Walter Maria de Silva who is another Grand Doyen of Italian car design; which may or may not tell us a lot about Italians' joint fascination with pasta and cars. And of designing pasta as being more akin to designing a car than sculpting.

Having explored pasta and design in context of industrialisation and the from giving process, those two aspects of design that are very much at the forefront of the design industry, of design as a commercial process, al dente moves on to discuss cultural aspects of pasta in three brief, inter-related chapters, starting with From poster to pleasure, an exploration of pasta and communication design, and thereby pasta and that design genre which in all its direct and abstracted contexts was not only an important one at the HfG Ulm, but that genre in which Otl Aicher not only began his career but is easiest to locate; a discussion primarily undertaken in al dente via a collection of advertising posters that help one better appreciate that the manner in which pasta is, and long has been, marketed has had an important influence on how pasta is perceived, on our associations with pasta, on our relationships with pasta, is a very neat case study in marketing establishing traditions and then reinforcing that invented tradition. Much as the myth of Marco Polo and pasta began, as far as we understand, in a marketing promotion. And is also a very neat case study in marketing establishing a tourist gaze through the influence of pasta marketing on popular perceptions of Italy.

Communication design that also includes the packaging design of the chapter From the ceramic jar to outer space, a chapter that neatly elucidates not only the changes in how pasta has been sold and distributed over the course of the past century or so, but also how developments in pasta packaging relate to wider changes in consumption and society, including, for example, the relevance of the rise of the supermarket in how pasta is packaged and sold, a state of affairs which tends to echo the role of the rise of first the department store and subsequently online shopping in how our other objects of daily use are packaged and sold; a chapter which reflects on contemporary attempts to develop pasta packaging more sustainable than one way synthetic plastics, and which forces you to question if a return to the unpacked of yore, to selling pasta loose by weight, isn't the only meaningful contemporary solution. Or selling pasta in large wooden crates. And also forces you to question the role of the myriad pasta forms in our contemporary resource and climate problems, ¿what if we only had 5 pasta forms, would that help through simplifying the selling and distribution of pasta? And a chapter on packaging design that also elucidates, and brings one back to the considerations initiated by From poster to pleasure on the semantics of pasta advertising, how pasta packaging is employed to serve the nefarious ends of l******** and t****, to induce us to buy particular brands, and that invariably at a price far above the actual value of the pasta contained within the meticulously and commercially developed packaging. But is well worth the exaggerated price for the Instagram post.

Financial gain, and the semantics of pasta, that are also a component of For kitchen and commerce with its presentation of objects inspired by or produced for pasta, objects which play with associations of and with pasta, and/or with the central place pasta in all its forms has in contemporary society, as the basis for objects created, formed, produced, purely with the intention of being profitable; thus objects that also take you back to the chapter Paths to new forms and the question al dente doesn't approach, and thereby admonishes, empowers, you to, on why we need novel pasta forms, why the need for paths to new forms, other than marketing and sales. The vernacular has but little interest in profit. But is generally more sustainable and unobtrusive than the academic approach. Which also brings one back to the question, what if we only had 5 pasta forms? ¿Would that be so bad? ¿How many different forms do you eat?

But a chapter that also helps elucidate how pasta has informed not only the development of cooking utensils and crockery but our use of kitchen and dining tools, not least the fork, an object presented in a variety of forms in al dente, and while we are a little sceptical, a lot sceptical, of the curators claim that the fork was invented specifically to aid the eating of pasta, we are more than happy to accept that the rise of pasta in Italy, and pasta's global dissemination not least in context of the many chapters of the global dissemination of the peoples of the contemporary Italy, did contribute, potentially contributed a great deal, to the establishment of the fork as the primary tool for eating, a tool unknown to the Romans. If a chapter that very notably doesn't include devices to make your own pasta at home, thereby tending to confirm the reality implied by Otl Aicher's unrealised electric pasta maker that the greater majority of us rely on industrial pasta from Teflon trafile, and that despite the fact we all know "there is nothing like real home grown spaghetti".

¿Home grown?

Home grown.

For a great many decades Panorama has been the BBCs most important news, investigation and reporting platform, a veritable British institution, a British authority. And all very, very serious stuff. As was their very, very serious report from April 1st 1957 on the 1957 spaghetti harvest in the southern Swiss canton of Ticino. A report that very pleasingly features in al dente.

A report in which, as the camera pans over trees laden with spaghetti, a very, very serious BBC English speaking narrator explains that this year was a bumper spaghetti harvest in the Ticino on account of the mild winter and the decline in the Spaghetti Weevil, the latter an utterly joyous attention to detail in a film that is still one the best ever April Fools jokes and a masterclass in comedy writing; the line "many of you, I am sure, will have seen pictures of the vast spaghetti plantations in the Po Valley" being one of our all time favourite lines. We've heard it a million times, and it never stops being funny.

If you've never seen it you must. Honest.

Not least because it is not just hilarious, but also highly informative.

On the one hand because Panorama was, then, such an authority: people believed it. Spaghetti was still relatively new in the UK in the 1950s, most Brits probably assumed it didn't grow on trees, no-one who watched the report had ever seen the "pictures of the vast spaghetti plantations in the Po Valley" the narrator devilishly takes as being self-evident and ubiquitous, but where did spaghetti come from, ¿does spaghetti grow on trees? Panorama said it did, and they were an authority, so it must. Today people still believe those they consider authorities, still believe that spaghetti grows on trees if an authority tells them it does; the difference is that today many of those popularly believed to be authorities aren't independent institutions seeking to explore contemporary realities and stimulate an open-ended discourse, but individuals with an idealogical world view to promote and establish and defend. Including via discrediting the independent institutions who threaten their rise through challenging their narrative. Which isn't hilarious. But needs to be made hilarious, à la The Great Dictator. And reminds of part of the reason the HfG Ulm was established, reminds that the remit of the HfG Ulm was designing society, designing democracy, as much as it was designing products and posters and pasta. Which it's important to remember.

And on the other hand, and returning to al dente, the manner in which the narrator explains that the fact spaghetti grows to a uniform length is "the result of many years of patient endeavour by plant breeders" allows for reflections not only on the consequences of human society's desires to control and harness the plant kingdom as discussed in and from Plant Fever. Towards a Phyto-centred design at Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden, but also on the standardisation and optimisation pasta and its production has undergone as it has moved from a home produced foodstuff to a mass produced commodity. Standardisation and optimisation that were subjects with which the HfG Ulm very much concerned itself, standardisation and optimisation that were one of the continuations in the 1950s and 60s of 1920s and 30s Functionalist Modernism, and thus one of several links between the HfG Ulm and the Bauhauses.

¿As is pasta?

Whereas pasta was, not least through the person Walter Zeischegg, definitely a thing at the HfG Ulm and amongst HfGler, its relationship with the Bauhauses is less well recorded; however, what is recorded is that the first pasta factory in the lands of the contemporary Germany was established in the late 18th century in Erfurt, but a penne's throw away from Weimar, and so theoretically, pasta could have been a regular feature of the menu in the Bauhaus Weimar canteen, we can well imagine, for example, veggie lasagne was popular during the Mazdaznan days of the earliest Weimar Bauhaus. We'd certainly believe it was if a very, very serious 1950s Panorama narrator told us it was. And not only could pasta have featured on the menu but one of Bauhäusler could have beaten Walter Zeischegg to the first contract with a manufacturer; the Bauhauses actively sought, were financially dependent on, cooperations with industrial partners, Kunst und Technik – eine neue Einheit, Art and technology – a new unity, was one of Gropius's more famous proclamations. It's not inconceivable a Weimar Bauhäusler could have cooperated with Erfurter Teigwaren.

¿But whom?

¿The expressionism of a Wassily Kandinsky?, ¿the quadratic of a Marcel Breuer?, ¿the fantasy of an Erich Dieckmann?, ¿the reduction of a Marianne Brandt? ¿or the silversmith approach of a Christian Dell, that first Plasticsmith?, that predecessor of a Walter Zeischegg, and thus surely the creative predestined to have developed novel pasta forms in and for the 1920s. Whereby we all know it would have been Ernst Neufert, because the industrialisation of pasta production, and the cultivation of spaghetti of uniform length, requires standardisation and optimisation. Standardisation and optimisation whose benefits the Functionalist Modernists unquestioningly believed in, much as British TV viewers belived in the spaghetti farming communities of the Ticino, but was their faith better placed? Is standardisation and optimisation the universal answer? Or are standardisation and optimisation cults we've taken way too far, which we treat dogmatically and employ unthinkingly, much as we employ terms like Bauhaus and HfG Ulm unthinkingly; are standardisation and optimisation the foundation on which many of our contemporary ills are constructed and from which we need to wean ourselves? Was it good that plant breeders forced spaghetti trees to produce a crop of uniform length? ¿Honestly?

Spätzle isn't standardised, can't be standardised. And thus while it may not be the Urform of Teigwaren, in discourse with pasta spätzle can teach us a lot.

al dente ends with From Pot to Museum, a brief look at pasta and art, pasta as art, no not the monumental, and deliciously unappetisingly critical, pasta art of Canadian collective General Idea as could be enjoyed in Everything at Once: Postmodernity, 1967–1992 at the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, but projects such as Erwin Wurm's photo series Nudelskulptur with its depictions of inter-relationships between spaghetti and people, objects, animals, or a collection of spaghetti based works by Italian creative duo Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, or the lamp Veramente al Dente by Ingo Maurer und Team, a spaghetti filled plate atop a pile of plates and a column of cutlery, and a lamp that on account of the fact every one is unique, and the question of whether its functionality or its poetry has primacy is a very nice framework for approaching the border between art and design. As is Indonesian born, Singapore based, Cynthia Delaney Suwito's Knitting Noodles project in which she painstakingly and with extreme difficulty and dexterity, knits instant noodles into a length of cloth, and thereby not only allows a myriad reflections on handcraft, utility, luxury, time, waste, society, instant noodles, etc, but also takes pasta in to the unexpected realm of textile design.

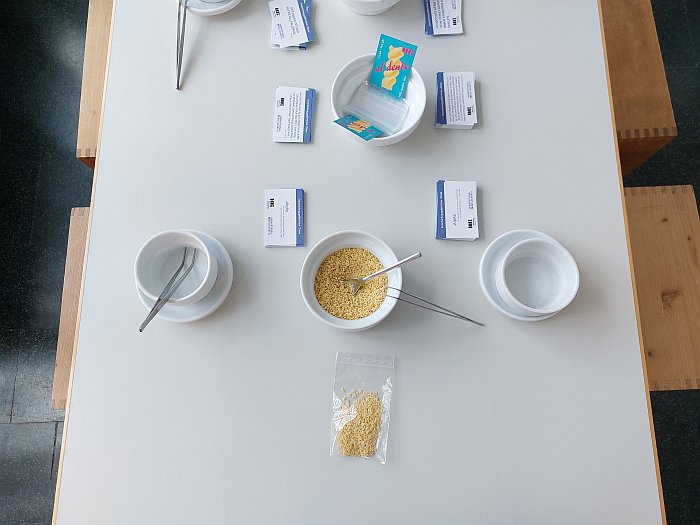

While the Coburg based platform Verwertungsgesellschaft a.k.a. Martin Droschke and Oliver Hess take pasta in to the realm of book design with their project Weltliteratur in Buchstabennudeln, World Literature in Alphabet Pasta, a library of works by the likes of, for example, Goethe, Beckett, Woolf, Zola, et al in alphabet pasta, to recreate as a book, or eat as pasta, as you see fit. And a Verwertungsgesellschaft who also invite all visitors to al dente to do their bit to make the world a better place by recreating disrespectful/harmful/dangerous phrases from alphabet pasta, then sealing them in a bag, and thereby taking them out of circulation, disarming them. We sought to do our bit by packaging up Luigi Colani's tirade "Ich spreche doch nicht mit den Ulmer!", 'I don't speak with the Ulmer!'

And pasta and art also inherent in the invitation made by al dente to create your own pasta art works, not necessarily akin to those of General Idea, although if you want to, and have the time, why not; but certainly an invitation to use the various forms of pasta, to use a collection of geometric forms, as building blocks for a work of art. And therefore not only an opportunity to reflect on the Bauhaus Vorkurs, and on the question if any of the results of that Bauhaus institution would be suitable as pasta forms, but also to reflect on the use of geometric forms as the basis for objects of daily use that is, inarguably, the basis of popular perceptions of the design approach of the Bauhauses; in which context one notes that alongside Mandala Philippe Starck also proposed Quartella, a novel pasta form featuring a triangle, a square, a circle and a diamond linked together, thus a very direct play on the popularly perceived geometricism of the Bauhaus design approach. A use of geometric forms as the basis for objects that was also a component of the approach of early HfG Ulmers, including the institute's founding director Max Bill, but which was thoroughly rejected by Otl Aicher who in criticising the Bauhaus approach once asked, "is design an applied art, does it appear in the elements square, triangle and circle, or is it a discipline that draws its criteria from the task, from use, from production and technology?"4 For Aicher the answer was the latter. Thus an invitation to create pasta art that is also an invitation to reflect on the many differences and similarities between the Bauhauses and the HfG Ulm, and to reflect on the pasta art work a Marcel Breuer would create, a Gerhard Marcks would create, a Max Bill would create, a Hans Gugelot would create or an Otl Aicher would create, and the whys and what that can teach us.

And also an invitation to reflect on any society as a composition of differently formed components.

Which yes, does bring us back to spätzle. And archetypes.

A bijou, a pastina, exhibition if one with a scope to feed the largest of appetites, al dente is a very colourful presentation, a brightness which not only neatly echos the gioia della vita of pasta, but also greatly aids the viewing, brings in a visual appeal that is always so important in the presentation of any foodstuff; and as such reminds that pasta is only a part of the whole, there is also the sugo, and as an exhibition al dente with its mix of objects, perspectives, design genres, positions and paths to apparently unrelated subjects, is a rich sugo that enhances the telling of the (hi)story, function, relevance and need for pasta.

If a sugo that can leave a curious, slightly salty, aftertaste, or the chapter From the ceramic jar to outer space can; a chapter on how pasta has been sold and distributed over the past century or so divided into the subchapters, Bags and Boxes, Sustainability, Lifestyle, World Literature in Alphabet Pasta... and DDR. A DDR that is presented in al dente by bags and boxes. Why suddenly introduce the DDR in the middle of a discussion on selling and distributing pasta? Why not Belgium? Or Sweden? Or Italy, that land where pasta has been sold and distributed the longest? We know, we know, but we're also hoping that isn't the reason; however, the presenting of West German pasta bags and boxes as Bags and Boxes and the presentation of East German pasta bag and boxes as DDR doesn't give us any real encouragement that our hope is well placed. It's not quite, 'Look mum, the Zonies had pasta!! Wow!!!', but it does tend to place pasta, consumption of pasta, relationships with pasta in the former east as being different from in the former west, something that distinguishes the east from west, that understanding of the two Germanys as two distinct (hi)stories that isn't really sustainable any more as we approach two generations since 1989 and the increased questioning, and increasing necessity, urgency, of questioning, the many Marco Polo-esque myths of the 1990s.

Yes, there were obviously differences, not least DDRler couldn't travel down to Italy to taste home-made pasta, buy a pasta making machine and then hide it in the back of their kitchen cupboard, that was the preserve of West Germans, no questions there were differences, including differences related to pasta; but the more honest and probable telling of the (hi)story of the years 1945-1989 that is necessary to allow the contemporary Germany to move forward requires an acceptance that the two Germanys didn't develop in splendid isolation either from one another or from global society, that thing that PURe Visions. Plastic Furniture Between East and West at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Dresden, did so elegantly, requires a lot less trying to find the good and/or bad in one as opposed to the other, a lot less separation of the (hi)stories, and certainly a lot less crowbarring East Germany into popularly accepted West German narratives, less adding the east to the west by whatever means possible, and more intertwining of the DDR and BRD as two different but equally valid and important components of an ongoing journey.

And thus for all we are happy to accept the inclusion of the DDR as a genuine attempt to make al dente a discussion for all of Germany as opposed to a discussion on a global subject from the western perspective so often taken in post-1989 Europe, the chosen method is very clumsy, not least because it makes no sense, why reduce the (hi)story of pasta in the DDR, why reduce pasta as a cultural and commercial good in the DDR, to bags and boxes?; it's all very VEB Pasta, that slightly less useful, more restricted, version of alphabet pasta with its limited possibilities of expression necessitated by the economic realities of the DDR, ¡¡we could only afford three trafile!!, rather than the (hi)story of pasta of east and west as self-obvious components of the whole that the contemporary Germany still struggles to be.

What bring us all together, what unites us all, what explains our differences as similarities, better than pasta? OK, Antilopen Gang argue pizza, but is pizza not just another interpretation of Teigwaren. Calzoni is but a big Italian dumpling.

After its run in Ulm al dente is due to be shown at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Künst in Leipzig, it would be very welcome if Grassi could lose DDR while including the DDR. They certainly have the space to expand all 6 chapters.

Not that such, not that the slightly salty aftertaste of From the ceramic jar to outer space, detracts from the enjoyment of al dente, it doesn't, it is but a brief moment in a long meal; and as a meal al dente is a well presented, satisfying dish with a nice mix of balanced flavours, that, and as with all good meals, leaves you replete but hungry for more a little later, once you've digested that which you have just consumed.

al dente: Pasta & Design is scheduled to run at the HfG-Archiv, Am Hochsträß 8, 89081 Ulm until Sunday January 19th, Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at https://hfg-archiv.museumulm.de

In addition a richly illustrated, German only, catalogue featuring a variety of essays around pasta and design is available.

1Otl Aicher in the film Otl Aicher, der Denker am Objekt, Angelika and Peter Schubert, 1991

2ibid

3Otl Aicher, Konzept einer Nudelmaschine für Braun AG, 1984, presented in al dente. Pasta & Design

4Otl Aicher, Bauhaus und Ulm, in Otl Aicher, Die Welt als Entwurf, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 2015, page 90