Human society's fascination with leaving behind the limitations and fragilities and vagaries of the human being, and of the planet we all call home, is almost as old as human society, and is inextricably linked with developments in technology, science, engineering and human society's understandings of itself and its environments; amongst the earliest descriptions, for example, of flying to the moon being Francis Godwin’s 1638 book The Man in the Moone, an account of a journey, and of the beings who call the moone home, published just 28 years after Galileo Galilei published the first detailed sketches of the surface of the moon. As soon as we 'knew' about the moon in 'detail', we wanted to be there. And wanted to get to know the natives. Whom we assumed existed.

And a fascination that, for want of a better phrase, took off, as space travel became a reality in the second half of the 20th century, and that at a time when there was an active desire to rebuild global human society after the trials, tribulations and Wars of the first half of the 20th century, a very real desire to leave behind the most recent chapter in human (hi)story and to write a new one. Ideally in a place far, far away from recent memory. And a desire to establish that new human society with the aid of that newest of human species: the designer. A species who had evolved from a synthesis of architects and artists and artisans in the course of the first third of the 20th century with the promise of providing for all.

With the actual moon landing on July 20th 1969, just 331 years after that first moone landing, anything and everything became possible. Science fiction was becoming science reality.

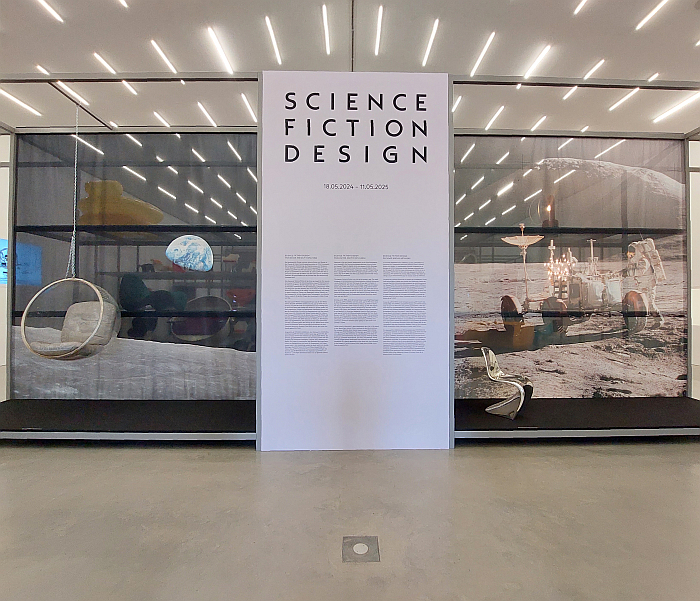

With Science Fiction Design: From Space Age to Metaverse the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Weil am Rhein explore science fiction and design, science fiction as design, design as science fiction, and in doing so invite you to re-imagine, re-construct, re-frame familiar narratives.......

As with the original Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot presentation concept, a presentation concept we presume has become, and will remain, one of the past rather than one of the future with the introduction of the year long intervention-esque presentation concept, Science Fiction Design: From Space Age to Metaverse is largely, +/-, a chronological journey, a journey through and across the past century and a bit of human society, science fiction, science reality and (furniture) design opening with pre-space age science fiction fantasies including, for example, introducing Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein, a work that enables a differentiated view on both Romanticism and Utopias, on Utopias as Romanticism, and which reminds that science fiction visions needn't be of the bright new future type, nor do Utopias often end as such, Utopias invariably reveal themselves as Dystopias; Georges Méliès' 1902 film Le Voyage dans la Lune, a work from the earliest days of film that used that most novel of media to take take the viewer to the moon much as the novelty of Galileo Galilei's telescope had once inspired Francis Godwin to take the reader; or William Cameron Menzies' 1936 film Things to Come, a film written by H.G. Wells, that Grand Doyen of visions of the future in the earliest years of the 20th century, a film based on Wells's highly informative 1933 book, discourse, The Shape of Things to Come, and a film which is (primarily) set in a futuristic underground city of the type, and as with a large part of Wells' canon, highly informative in context of what would come in both science fiction and science reality.

Pre-space age science fiction fantasies accompanied by examples of contemporaneous design including, and amongst other works, a unit from Paul Theodor Frankl's 1920s Skyscraper Furniture series, a model of Richard Buckminster Fuller's 1927 Dymaxion House, or an early 1930s steel tube chair by Erich Dieckmann through Cebasco which reminds that not only is the (hi)story of steel tube furniture a lot wider and a lot more interesting than the popular narrative would have you believe, but that the 1920s and 30s weren't just quadratic reduction, they were also highly sculptural and expressive.

And then, to paraphrase H.G. Wells, that thing came that would prove so fundamental to things to come in terms of science fiction: the Space Race of the 1950s and 60s and the 1969 moon landing.

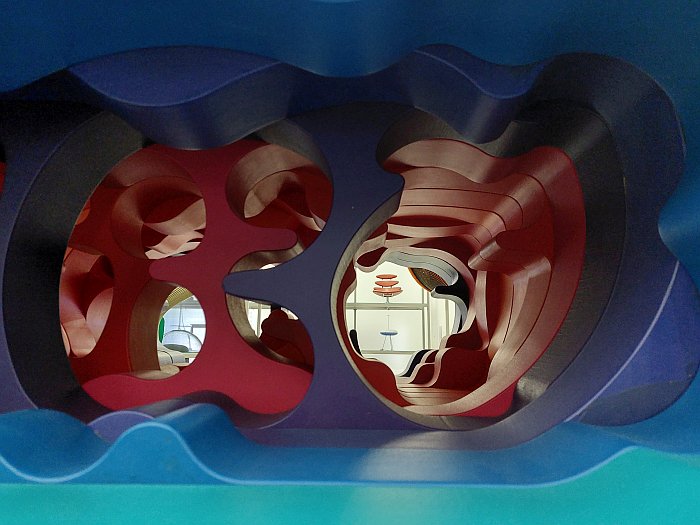

A shift from a long held desire to explore the universe, and to visit the natives of the moone, to an urgent race to space that primarily occurred in context of the Cold War, became a Space Race stoked and defined by the tensions of the Cold War; and an era explored in Science Fiction Design from a number of perspectives including, for example, science fiction interpretations of the Space Race and the space age reality it would unquestionably initiate as visualised in television shows of the 1960s and 1970s, including Star Trek, that genre defining series, or through novel interior concepts of the period as developed by, for example, Luigi Colani, Joe Colombo or Verner Panton, the latter represented by his 1970 project Visiona II for Bayer, a sweeping, fluent, tactile, sensuous, rainbow in which to immerse yourself and escape the 1970s. Or the 2020s.

If the Cold-War had been a driving impetus behind the Space Race of the 1950s and 60s, and had thus been an important fuel of the science fiction of the period, the events in Europe, and elsewhere, in 1989, not only led to a re-ordering of relationships within Europe, but also saw, after bursts of excitement at the novelty of NASA's Space Shuttle and the Soviet Union's Mir space station in the 1980s, interest in the galaxies and universes beyond our own wane. Not least because new economic realities and geopolitical complications shifted human society's priorities from space to planet. In addition post-1989 there was, and as discussed by and from 1989 – Culture and Politics at the National Museum, Stockholm, a new, to paraphrase Star Trek, final frontier to be approached, one even more expansive, and much less tangible than the universe: The Simpsons..... Doh!... the first manifestations of the World Wide Web.

A World Wide Web, a novel technology, that the more it became understood not only opened up ever new ways for the human species to torment and cheat and hurt and bully one another, new ways to wage war, exert authoritarian control, to expand our egos into public space, but also allowed ever more opportunities to escape the limitations and fragilities and vagaries of the human being and the planet we all call home. An increasing understanding of the possibilities of the World Wide Web and digital technology that saw interest in physical galaxies and physical space increasingly being replaced by a fixation on and fascination with virtual galaxies and virtual space, a period when 'space age' increasingly ceased to be the tangible of rockets and planets and robots, OK our fascination with robots remains unbroken, and became the exploration of the intangible of computers, the internet, social media and the metaverse.

New possibilities, positions towards the new possibilities and expressions of such approached in Science Fiction Design through projects such as, and amongst others, Studio Formafantasma's Ore Streams Low Chair, the so-called Scorpion Computer Cockpit by Cluvens, the Sketch project by Front, or the Hortensia Chair by Andrés Reisinger and Julia Esque, a work that began as a digital rendering in dimensionless virtual space before becoming a physical chair in the confines of our physical space. With all the connotations that has and had for the work, its function and the relationships we can develop with it. And a work by an André Reisinger who is responsible for the exhibition design of Science Fiction Design.

A Science Fiction Design, a journey through and across a century and a bit of human society, science fiction, science reality and (furniture) design that through the dialogue it establishes on its path between (furniture) design, science reality, science fiction and human society enables, much as science fiction enables wider perspectives on, and encourages a critical questioning of, the subjects at hand, wider perspectives on and a critical questioning of design and of the relationships between design and humans, individually and collectively.

Amongst the many threads that run through Science Fiction Design's 11 succinct chapters, and which help you navigate the exhibition's physical space as much as its theoretical space, one of the most prominent is without question furniture design and science fiction films, a thread, a subject, whose prominence and centrality is underscored through it having its own chapter, Design on Film. A chapter which argues that furniture is often used to bring an authenticity to a scenography, an 'authenticity' that forces you to question what is 'authentic' in an imagined, invented, scenario? What is 'authentic' in an imagined, invented, space? Which yes could bring us all back to considerations on garden architecture, and landscapes in general, as discussed in context of Re:Generation. Climate change in a natural World Heritage Site – and what we can do about it at Park Sanssouci, Potsdam, but instead takes you to, for example, the alternative 1970s of a Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Welt am Draht, the early 21st century outer space of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, or the late 21st century of Ridley Scott's Prometheus via objects such as, for example, and amongst others, Marc Newson's 1993 Orgone Chair for Pod as employed in Prometheus, the 1962 042 chair by Geoffrey D. Harcourt as seen in 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Joe Colombo's 1965 No. 4867 chair for Kartell from Welt am Draht.

A discussion continued at various locations throughout Science Fiction Design including by, for example, the 1897 Argyle Chair by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, a work designed for a 19th century Scottish tea room that became part of a futuristic 2019 Los Angeles in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner; Atelier de Recherche Plastique, ARP's, mid 1950s steel wire and plastic cord lounge chair for Etablissements Rougier that appears in Mon Oncle, Jaques Tati's vision, criticism, warning, parody, of where post-War Functionalist Modernism, and post-War science fiction, was taking society; or Maurice Prentice Burke's 1966 116 armchair for Arkana, that chair that is so ubiquitous in Star Trek, which was such a loyal servant on their five year mission, and which as the curators note is, essentially, a copy of Eero Saarinen's mid-1950s Tulip armchair, an object which can be viewed in the orbit of Burke's 116. And a relationship between the 116 and the Tulip which obviously poses tricky questions on the 'authenticity' of Star Trek. And on the honesty of the United Federation of Planets and thereby their suitability to govern so much space and time.

And examples of furniture used in science fiction films and tv series that forces you to question why directors use existing furniture objects to portray the desired 'authenticity' of their imagined, invented space rather than commission furniture designs for their science fiction visions? They could have done, there was nothing to stop them. And there are many examples of directors doing just that, Science Fiction Design also presenting, for example, Ruedi Giger's so-called Harkonnen Chair, an object designed by Giger for use by Baron Harkonnen in an, ultimately unrealised, film adaptation of Frank Herbert's novel Dune, and also featuring a photo of the Throne of Wakanda from Ryan Coogler's 2022 film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.

¿Why use real, existent furniture objects in an invented, imagined, non-existent space?

A discussion of furniture in science fiction films, and a questioning of why not commission furniture to reflect the 'authenticity' of a film rather than using existing works, ¿why transpose a real 1897 Scottish chair into a fictional 2019 California?, that recalls the discussion of furniture in comics presented in context of the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot's showcase Living in a Box. Design and Comics; memories of Living in a Box reinforced in Science Fiction Design in the forms of, and amongst other works that feature(d) in both, Eero Aarnio's 1971 Tomato chair, Michele De Lucchi 1982/83 chair First or Maurice Calka's 1969 Boomerang desk through Leleu-Deshays, the latter a work that featured in Living in a Box in context of a discussion on the Space Race of the 1950s and 60s, and which features in Science Fiction Design in context of a discussion on the Space Race of the 1950s and 60s. And a Boomerang which having now been thrown into the conversation, will return in a couple of minutes.

And a comparison of furniture in comics and furniture in film, and a questioning demanded by Science Fiction Design of furniture's role in 'authenticating' space, furniture's role in bringing an 'authenticity' to an imagined, invented, space, that allows one to approach a better appreciation that not only does furniture have a semiotic function, transmits signals and messages that others can read, be that in films, comics, advertising, office building lobbies, hospitality or the staging of your own private interior as a public spectacle, but also that through the use of furniture in specific popular cultural contexts the registers we all employ in context of furniture become expanded, furniture takes on meanings and associations it never had, doesn't naturally posses, thereby expanding the array of readable messages furniture transmits. And also helps elucidate that it's an active, ongoing process.

And in doing so, in enabling access to such reflections and consideration, Science Fiction Design also poses the question as to which associations came first: do we associate furniture with science fiction or science fiction with furniture. A (near) classic chicken and egg question.

A chicken and egg question that is easily transposable to the great many other associations we all make in context of furniture, the great many other messages we can and do read in furniture, the great many registers we employ in context of furniture; and a chicken and egg question you can reflect upon in Science Fiction Design in context of an actual egg, specifically Arne Jacobsen's 3317 Easy Chair for Fritz Hansen a.k.a. the Egg, a work that, as previously noted, is essentially nothing more out-of-this-wordly than an old school wing-backed armchair, but a work that is truly forward looking, truly futuristic, a herald of a coming intangibly tangible brave new world, a herald of things to come, thanks to the styropor from which it's core is formed, a material that was so novel in the 1950s it initially "frightened" Jacobsen1, much as Martian robots frightened 1950s science fiction fans.

And a reinterpretation of the past in a future material that famously took up residency in that most focussed of demonstrations of the contemporaneousness of 1960s Denmark, that construction that confirmed Denmark had left behind the craft and handwork society of yore — yes, we know, we know, we did it deliberately — and was embracing the possibilities inherent in novel post-War science and technology: the SAS Royal hotel in Copenhagen. A use of Jacobsen's Egg in Jacobsen's SAS Royal, a repeated and regular use Jacobsen's Egg as a marketing tool of and for Jacobsen's SAS Royal, that not only made and makes Jacobsen's Egg inseparable from Jacobsen's SAS Royal, but that placed and places Jacobsen's Egg at the heart of the 1960s.

A use of Jacobsen's Egg in Jacobsen's SAS Royal that finds an echo in the use of Jacobsen's Egg in the headquarters of the organisation Men in Black in Barry Sonnenfeld's eponymously titled 1997 film, a use, an echo, intended to underscore the 1960s setting in Men in Black, a setting in a 1960s America the Egg wasn't necessarily designed for, but which in context of Men in Black it took up residency; and an echo in a film that tends to bequeath the Egg an Americaness, tends to make the Egg a component of an American mid-century Modernism it never was or had.2 Yes, there are comparisons that can and should, must, be made to the works of the Eames and Saarinen, but the Egg stands primarily in context of Jacobsen's oeuvre and positions and approaches, is an Egg that Jacobsen arguably could have produced, laid, at numerous moments in his career, is an Egg that arose in context of and through the positions and approaches Jacobsen had developed over his decades of practice.

Is Jacobsen's Egg 1960s? Or is Jacobsen's Egg 1960s because of the stage setting it performed in films and advertising? Is Jacobsen's Egg 1960s because of a conditioning through popular culture? Or is the popular view of the 1960s because of Jacobsen's Egg? Is the 1960s Jacobsen's Egg? What came first, the 1960s or Jacobsen's Egg?

A Jacobsen Egg that also populated Ringo's Blue Zone within the Beatles' shared house of their 1965 film Help!, a, if one so will, Beatlechair in Help! rather than a Beetlechair by Alexander von Dombois that is a cry for Help!; a use in Help! that, well... Helped! place Jacobsen's Egg as a component of Swinging Sixties London, Helped! confirm Jacobsen's Egg as 1960s, Helped! enable us to read Jacobsen's Egg as 1960s, and to question if it is and ever was; a Swinging Sixties London to which Nanna Ditzel's 1969 OD 5301 armchair, a work on show in the vicinity of Jacobsen's Egg, and which was realised, certainly finalised and produced, in context of Ditzel's time living and working in the English capital in the late 1960s, may or may not have been informed by, but which can today be read as being Swinging Sixties London.

And a 1965 Beatles interior that, arguably, is much more science fiction than those of Joe Colombo or Verner Panton, interiors whose science fiction labels are arguably more a matter of ex post facto conditioning as mediated through film, comics, book, marketing, et al, a science fiction through association, than any conscious act on the part of Colombo or Panton who both very much designed for a now as they perceived it3. If a Beatles' interior arguably on a par with Alison & Peter Smithson's 1956 House of the Future which also features in Science Fiction Design, a Smithsonian House of the Future that, as the name implies, is a house of the future, not a house of the now; a Smithsonian House of the Future that in contrast to Arne Jacobsen and Flemming Lassen’s round 1929 Fremtidens Hus, and in contrast to our postulation from Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński at the Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław, that the house of the future is always round, isn't round. Our argument is however supported in Science Fiction Design by Buckminster Fuller's 1927 Dymaxion House, Bucky's house of the future, one of Bucky's houses of the future, which is round, or almost, is a pentagon, so round with corners. Much as Tsuyoshi Tane's memory of the future Garden House on the Vitra Campus is round in that it's an octagon.

And a Jacobsen Egg whose styropor core is also a component of another instructive and informative thread that runs through Science Fiction Design.

Is also a component of further reflections on cultural conditioning, association and chicken and eggs in context of furniture design.

That of the materials of furniture design.

Maurice Calka's 1969 Boomerang desk, we told you it would return, featured and features in Living in a Box and Science Fiction Design not only in context of the Space Race of the 1950s and 60s, but also in context of the novel synthetic plastics of the period; novel synthetic plastics that, as opined from PURe Visions. Plastic Furniture Between East and West at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Dresden, were the real revolution in context of furniture and furnishings of the 1930s but which then weren't of a durability that allowed them to be used for more than the accessories, crockery, lamps et al developed by pioneer plasticsmiths such as Christian Dell; that the popular focus today of 1930s furniture and furnishings is on steel tubing is (primarily) because steel tubing was science reality, synthetic plastics were still science fiction, certainly in terms of furniture and furnishings, in the 1930s, increasingly became science reality in the 1940s and 1950s through developments such as, for example, fibreglass or styropor before in the form of polyurethane anything and everything became possible, much as it had with the moon landing of 1969.

A moon landing that came a year after Vitra launched the eponymous Panton Chair as the first chair formed in polyurethane from a single mould, a Panton Chair that as a cantilever chair symbolically brought the 1930s steel tubing work of Marcel Breuer, Mart Stam, the brothers Rasch, et al into the 1960s, confirmed that synthetic plastics were the real revolution of the 1930s; but for all a Panton Chair that proved the suitability of polyurethane for furniture. A polyurethane which opened up possibilities for furniture designers as unlimited and unexplored, and as previously unimaginable, as that vastness of outer space Domingo Gonsales had traversed in 1638. Polyurethane, and other synthetic materials, that allowed an opportunity to escape the formal confines of wood in context of furniture and furnishings, much as reinforced concrete long had in terms of architecture, and thereby allowing an opportunity, at least by proxy, to escape the confines and restrictions of human society and its planet, to explore strange new worlds of possibility and adventure.

Possibilities and opportunities and adventures of polyurethane, and other post-1940 synthetic plastics and related materials, that abound in Science Fiction Design including, for example, Günter Ferdinand Ris and Herbert Selldorf's ca. 1970 Sunball for Rosenthal, a spheroid room-within-room sofa concept crafted (primarily) from fibreglass; Luigi Colani's 1972 Der Colani for Top System Burkhard Lübke, his re-imagining in polyethylene of the Victorian reading chair with its yoke-esque backrest; Matti Suuronen's 1969 fibreglass reinforced plastic chair that looks as if he's loped the top off an egg, Jacobsen or otherwise, and then used the top as an abstract egg cup; Louis Durot's 1970 Aspiral, aspiral-ling snake in polyurethane that openly challenges conventions on chairs and sitting; or the eternally returning Boomerang a work in glass-fibre reinforced polyester. And, inevitably, by Panton's eponymous polyurethane cantilever in a couple of variants.

An abundance of synthetic plastics in Science Fiction Design in context of the furniture of the 1950s, 60s and 70s reflective of the popular narrative of furniture design (hi)story which tends to see synthetic plastics and the Space Race as having had an inter-related influence on the development of furniture design in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, of their being a direct interplay between synthetic plastics and the Space Race in context of furniture design of the 1950s, 60s and 70s; in, for example, Möbel aus der Zukunft. Eine deutsch-deutsche Geschichte, an easily recommendable, if sadly German only, book whose research was so fundamental to the development of PURe Visions, and a copy of which is available in the tri-lingual German/French/English library corner, library moon base, of Science Fiction Design, author Sascha Lange refers at length to the associations between the Space Race, space age, and synthetic plastics, about how the Space Race influenced and informed design, influenced and informed the forms of our furniture. As does Science Fiction Design. As did Living in a Box. As do an awful lot of tellings of the (hi)story of 20th century furniture design.

But is it so? Was there an association then, or do we make the association now? Do we associate synthetic plastic furniture with the Space Race or the Space Race with synthetic plastic furniture? And which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Viewing Science Fiction Design, and indeed viewing PURe Visions, is to be empowered to actively question the popular narrative of synthetic plastics and the Space Race as being one and the same, as being inter-related, in context of the development of furniture in the 1950s, 60s and 70s

Or perhaps better put, viewing Science Fiction Design, and viewing PURe Visions, is to be empowered to actively question the references made in Science Fiction Design to links between the Space Race, synthetic plastics and furniture design, to be empowered to attempt to contradict Science Fiction Design, which, no isn't a criticism, any and every exhibition should, must, actively empower you to contradict it. But for all is to allow for a reassessment of the popular narrative of synthetic plastics and the Space Race as being one and the same, as being inter-related, in context of the development of furniture in the 1950s, 60s and 70s; is to allow one to approach an appreciation that the connection that can, must, be made, is not a direct physical one of form or material or function, but an indirect conceptual one of the (apparent) limitlessness of the exploration possible, the invitation inherent in both space travel and synthetic plastics to explore strange new worlds, to boldly go where no one had gone before. But where people were very keen to go, had been yearning to go for a long, long time. In terms of furniture not necessarily since 1638, but, arguably, since at least that period in the early 19th century when a young Victor Frankenstein was exposing the residents of Ingolstadt to an incalculable terror.

A yearning to explore strange new worlds, to boldly go where no one had gone before, tending to be underscored in Science Fiction Design in the form of Joe Colombo's utterly delicious and endlessly engaging, mid-1960s Sella chair for Kartell, a work in moulded plywood, and steel, from a period of intense development on synthetic plastics, that is simply waiting for an appropriate solution in synthetic plastics to be developed. Colombo, one gets the impression, is thinking in synthetic plastic, but being forced to work in wood. Much as one gets the impression was the case with Bodo and Heinz Rasch in context of their 1927 wooden cantilever chair, a work that you sense wants to exist in Bakelite, but can't. Must wait. And that, in context of Colombo's Sella, at Kartell who are and were so important and influential in the development of synthetic plastics in Europe. But at that time didn't have the answer Colombo needed.

Similarly an argument can be made, one we have made, that Jacobsen's Egg was only possible because of styropor: although the Egg fits effortlessly in Jacobsen's oeuvre, Jacobsen's oeufre — Sorry!!!! (but it was very satisfying) — it wasn't possible, he couldn't have realised it, until the late 1950s when he was handed a terrifying novel material, and had to find a way to work with it that made it less scary. Which, yes, needs to be considered as a component of the above posed question as to if the Egg is or isn't a 1960s chair. Is Jacobsen's Egg 1960s because of the styropor? And if it is, what does that teach us?

Thoughts on Colombo, the brothers Rasch, and a Arne Jacobsen and his styropor Egg, that reinforce that furniture designers, as with architects, are, essentially, duty bound to use novel materials and novel technologies to develop new forms, new functionalities, new relationships, new furniture, it's one of those furniture designers do, is a key function of furniture design; a process that needs must begins in the past and works its way through the now into the future. And that was what many designers on the 1950s, 60s and 70s did, they took on the invitation and challenge of the novel materials and technology of the period to develop novel forms, functionalities, relationships, novel furniture. Space Race or no Space Race they would have done exactly the same.

And which is also what many designers in the 21st century do, something underscored in Science Fiction Design by works such as, for example, and amongst other Jólan van der Wiel's 2011 Gravity Stool which uses the science reality of gravity to create furniture reality; or the 2012 carbon fibre reinforced polymer L1 stool by a team from the Faculty of Design at the Hochschule für Technik und Wissenschaft Dresden and the Leibniz-Institut für Polymerforschung Dresden; or Joris Laarman's 2013 Aluminium Gradient Chair, a work developed with the aid of contemporary digital technology in a long-established material of furniture construction that helps one trace the (hi)story of novel materials and processes, the (hi)story of developments in technology, science, engineering as components of, as driving impetuses of, furniture design, as a key function of furniture design, not just back to synthetic plastics, but to aluminium as employed, for example, in Gerrit T. Rietveld's 1942 chair, a work that should, must, be studied in Science Fiction Design in dialogue with Laarman's, and can be followed even further back, not in Science Fiction Design but in your brain, to a Michael Thonet and bentwood. Arguably a little further back to a Karl Friedrich Schinkel and cast iron. And possibly to the Bronze Age.

A trail through (hi)story that in underscoring the importance of novel materials and processes in the development of furniture, allows access to appreciations that the invitation to explore the novel possibilities and opportunities of space and of synthetic plastics occurred not only by pure coincidence simultaneously, they are in themselves not linked, but that both occurred in a period when the desire to leave behind the recent reality of human society and to forge a new society, was approaching the manic; for lest we forget the 1950s and 60s of the Space Race and moon landing was also a 1950s and 60s that had seen the myriad frustrations of the post-War generation with the conventions and standards and relationships and furniture of the pre-War generations boil over and pave the way for a new society based on new conventions and standards and relationships and furniture. Much as moments such as Memphis or Neue Deutsches Design arose in the bubbling social ferment of a 1980s that exploded in 1989 to bring in a period of interior calm. With its Feng Shui. And futons.

And a 1968 reality that, arguably, was more relevant to developments of furniture in the 1970s than the events of 1969. Is just a lot less entertaining to reflect upon. And a lot less marketable. Space is always more fun, and more commercially promising, than civil unrest. And probably always will be.

And a necessity of a questioning of the narrative of the Space Race and synthetic plastics in context of the (hi)story of furniture design that tends to be supported in Science Fiction Design by the absence, unless we missed them, which is always possible, of the Eames' 1940s fibreglass chairs, works whose development is so indicative of the move away from established materials of furniture to visions of a brave new future, including being an important moment in the move from moulded plywood to moulded synthetic plastics. But works that no one would ever describe as 'space age', rather they tend to labour under the intolerable ignominy of 'Retro' that most pejorative, insulting, of terms for any object of design. And is certainly underscored by the absence of the Eames' 1948 La Chaise, a work in fibreglass developed parallel to, in context of, the fibreglass side and armchairs and which is surely the forerunner to the great many 'sculptural', flowing organic chair forms on show in Science Fiction Design and which stand proxy for the inter-relation between the space age and synthetic plastics in the development of furniture design. But a La Chaise which, again, no one would ever call science fiction design or space age design. But if you follow the popular narrative, it must be. Unless that popular narrative is flawed. Or is the 1940s too early? Were the Eames, as with a Francis Godwin or a Georges Méliès, 'space age' before space age was a thing? The Eames were a lot of things very, very early.

A question that can be approached in Science Fiction Design in the form of the Eames' Galaxy lamp, a work from 1949 that made its commercial debut in 2023 through Cassina, and that in a 2023 construction that is a much more refined, and for all a much more electrically safe, version than the original bricolage of automotive parts and a croquet ball from 1949; an Eames lamp from 1949 that, as noted in our post on Eames Lighting Design, was in all probability designed not by Charles and Ray Eames but by Don Albinson, that stalwart of the early Eames Office and who was closely involved in, fundamental to, the development of a great many Eames' designs of the 1940s and 50s; and an Eames lamp from 1949 named Galaxy in 1949 and thus in a period before we'd began visiting the actual galaxy. Much as La Chaise is a space age design before the space age could meaningfully influence and inform design.

And a Galaxy lamp that, as previously noted, was designed shortly after the Ball Clock by George Nelson, or possibly by Irving Harper, or possibly by Richard Buckminster Fuller, or possibly by Isamu Noguchi, or possibly by all four, and of which Galaxy is, arguably, a multidimensional reimagining. A science fiction extrapolation of time and dimensions that liberates light energy from molecules.

Beyond the very obvious synthetic plastics Science Fiction Design also allows for reflections on the use of aluminium as a material for furniture design, for reflections on the use of aluminium by human society for its tools and spaces; a use of aluminium that in Science Fiction Design starts with Rietveld's aforementioned 1942 aluminium chair, a chair produced at a time when aluminium was still a relatively forward looking material that would improve life on earth for us all, and continues over works such as, for example, Frank Lloyd Wright's mid-1950s office chair for his H. C. Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, or a contemporaneous ashtray by Eero Saarinen for Knoll, the latter a nice reminder that back in the day designers designed ashtrays because ashtrays were a common object of everyday use, and also a reminder that some of that which even the most progressive of designers create becomes obsolete and anarchic as societies and cultures develop and move forward.

And mid-1950s aluminium objects from a period when, and as discussed from Into the Deep. Mines of the Future at the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen, everyone who mined and used aluminium knew our mining and use of aluminium was unsustainable and irresponsible and problematic, but kept mining and using ever more aluminium. And that, arguably, because much as with synthetic plastics, shimmering, shining, mouldable, weightless aluminium offered a path away from the recent past and towards a glorious future; an association of aluminium as something positive and desirable, of aluminium as a shimmering, shining, mouldable, weightless future, that can also be understood in, for example, a Hans Hollein's use of aluminium for the interior and exterior of his mid-1960s Retti candle flagship store in downtown Vienna, or the use of aluminium for the outer face of the spheres of the Atomium in Brussels, that symbol of the 1958 World's Fair, symbol of the hope of the 1950s, and a model of which can be viewed in Science Fiction Design. If an Atomium that was formally based on an iron crystal, is a construction whose aluminium clad spheres are actually symbolised iron atoms, and thus an indication that far from looking to the future, the Atomium is hankering after the past. And thus a questioning if our contemporary visions of, and fantasising after, Retrotopias are also an expression of science fiction. And if our hankering after 1950s and 60s science fiction is also an expression of a Retrotopia. And if it is could, will, must, they become a Retro(dyst)opia?

An association of aluminium as something positive and desirable, of aluminium as a shimmering, shining, mouldable, weightless future, when everyone knew it was in fact moving us towards an unsustainable and irresponsible and problematic future but did nothing about it because there were visions to be chased, that can also be reflected on in the (we presume recycled) aluminium, and mobile phone components, of Studio Formafantasma's Ore Streams Low Chair, a chair that arose in context of a 2017 project concerned with what Studio Formafantasma refer to as "above ground mining", the salvaging and recycling of the materials of contemporary society's tools and spaces, for all those materials of contemporary digital society, the salvaging and recycling of our e-waste, the salvaging and recycling of the materials of our exploration of, fixation on and fascination with virtual galaxies and virtual spaces.

An Ore Streams Low Chair that enables a direct connection to be made between our relationship with aluminium in the 1950s and our relationship with rare earths in the 2020s, between society's 'need' for aluminium in the 1950s and 'need' for rare earths in the 2020s, between the advantages of aluminium in the 1950s and the advantages of rare earths in the 2020s, between the problems of aluminium in the 1950s and the problems of rare earths in the 2020s, between our sourcing of aluminium in the 1950s and our sourcing of rare earths in the 2020s, between the recycling of aluminium in the 1950s, recycling of synthetic plastics in the 1980s and recycling of rare earths in the 2020s.

And thus a Ore Streams Low Chair that helps elucidate not only how incapable as a species we are of learning from the experiences of the past, focussed as we all are permanently on the future, but also that while the dangers faced in the explorations at the Space Age end of Science Fiction Design's timeline, the dangers faced in the explorations at the Space Age end of Science Fiction Design's journey through and across the past century and a bit of human society, science fiction, science reality and (furniture) design are and were fictional 4, the dangers faced at the Metaverse end of the timeline/journey, are real, both in terms of the harm being done to the fabric of society through the manners in which we employ digital technology, and in terms of the viability and health of the planet we call home, and all kinda rely on, on account of how we produce, employ and dispose of that technology.

And also reminds that the journey from Space Age to Metaverse is bringing us back to Space Age in context of plans for mining the moon; moon mining not just in context of the rare earths needed for digital technology but also, for example, for the raw materials for the nuclear fusion reactors that have been a vision for decades, have been the answer to all our malaises for decades; and plans for mining the moon that, as noted from Into the Deep, for all they sound like science fiction are rapidly becoming science reality.

The Mine in the Moone could be with us before we know it.

Or are prepared for it.

2024 is an apposite moment for us all to ask ourselves if we want that, to ask ourselves if that is desirable, is that a near future vision we are comfortable with. What are the alternatives?

That thing we needs must always do with science fiction, that function of science fiction in helping human society feel its way forward.

Featuring around 100 objects set in a scenography by André Reisinger that through its use of mirrors turns the Schaudepot into a space (apparently) as endless as the universe, the metaverse, synthetic plastics or the realms of science fiction, and thus, as it were, an authentic setting for encouraging you to engage with the dialogue it initiates, Science Fiction Design is a well paced presentation whose concise bilingual German/English texts introduce themes but largely leave you to engage with the works yourself. A presentation that in its mix of objects, films, posters, comics, and a library corner, library moon base, equipped with texts of fiction and fact for visitors young and old alike, allows for various and varied approaches to the varied and various components of its dialogue.

If a presentation that succumbs to the limitations and fragilities and vagaries of the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot and places objects on the top shelves of the display shelving, toppermost shelves that, as oft noted, bemoaned, decried, in these dispatches, are simply to high to be meaningful for the presentation of furniture, are at a height that deny any practically useful viewing of objects of furniture. As we wandered through the landscape we couldn't help thinking that, and remaining in context of authenticity of scenography, it would have been good had the Vitra Design Museum provided jet packs to allow you to rise up and view the toppermost objects, or telescopes, periscopes even, if the local Health and Safety authorities had expressed concerns at jet packs in a confined space; for without such aids viewing some of the highest objects is a bit like viewing Mars with the naked eye, or the moon through Galileo Galilei's early 17th century telescope, you can see them, be aware of them, but.....

And while we're being critical of the display, there is, for us, something not only a little opportunistic in setting the 2005 chrome version of the 1968 Panton Chair as a component of David Scott's 1971 photo of the Apollo 15 mission cruising the moon in its Lunar Roving Vehicle, but also something a little unfortunate as it tends to reinforce the conditioned associations we make with furniture, tends to imply a chair that began life in 1950s Copenhagen, a place that, despite what Jacobsen's SAS Royal tries to tell you, wasn't space age, in many regards was just catching up with the earliest manifestations of the industrial age, tends to imply that chair is related to the space age. Tends to confirm the popular narrative of 1950s, 60s and 70s furniture design. And thereby tends to contradict the paths of exploration Science Fiction Design otherwise empowers you journey. And does that at the very beginning of the presentation. And thus a setting of a Panton chair on the moon that through confirming associations invariably held by the viewer on entry, through confirming that the Panton Chair is space age, for all in the limited edition chrome version, can distract from the further viewing of the presentation.

Similarly for all there is an unquestionable, and not in the least unsatisfying, echo in the hanging of Eero Aarnio's 1968 Bubble Chair as a component of William Anders' 1968 Earthrise photo from the Apollo 8 mission, it does tend to lead one to form associations that are not only non-existent but harmful in context of viewing Science Fiction Design: not only was the Bubble Chair developed before Earthrises were popularly known as an actual thing, but the Bubble Chair was developed because Aarnio wanted to place the sitter in a transparent space, if one so will a transparent version of his Ball Chair, in a bubble, and, arguably, we weren't there we don't know for sure, but arguably there wasn't a single reflection on space in that process, the association with space is something that has been popularly built in to readings of the Bubble Chair through association, such as with the slightly later Earthrise. ¿Which came first Bubble Chair or Earthrise? Bubble Chair.

And through the development of his bubble Aarnio, in his telling of the story, came to the opinion it wasn't possible to form and realise an aesthetic and meaningful transparent pedestal for a bubble. So he hung it from the roof. Much as in 1930 Friedrich Kiesler had hung his Flying Desk from the roof.

A Friedrich Kiesler whose great many forward looking projects wouldn't be out of place in Science Fiction Design, not least his Endless House, his house of the future, a house of the future that isn't round, or needn't be, it can be round, but is more normally ovate, there's those eggs again; but primarily a Friedrich Kiesler whose scenography, 'whose authentic' scenography, for the 1923 German language premiere of Karel Čapek’s 1920 play R.U.R. Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, R.U.R. Rossum's Universal Robots, a wonderful example of not only 1920s Czechoslovakian science fiction but of avant-garde positions in that fledgling Czechoslovakia, reminds that not only is and was science fiction an international movement, but reminds that the Space Race was an important component of the Cold War. And that any and every 'race', by necessity, needs at least two protagonists.

Thoughts which cause you to look around you in the Schaudepot and to appreciate that Science Fiction Design has a very strong American and western European focus, there's essentially no design from the other side of the Iron Curtain, from those other Space Racers. Nothing in fact, unless we missed it. Yet all rationale, reasoning and argumentation leads you to understand that there are and were objects on the eastern side of that former physical divide that could and would have effortlessly fitted in to the presentation, could and would have illustrated the chapters, themes and positions, would have been expressions of the (apparent) limitless of the exploration possible, the invitation inherent in both space travel and novel materials to explore strange new worlds, to boldly go where no one had gone before, and thereby would allow Science Fiction Design to tell a more probable account of the development of human society, science fiction, science reality and (furniture) design in the years under review.

That such isn't on show is, arguably, because the Vitra Design Museum collection doesn't have that much eastern European or Russian/Soviet Union design, be that from the Cold War years, before or since. Which isn't to point fingers of blame at the Vitra Design Museum, it isn't, is to use the Vitra Design Museum collection to highlight and underscore that the (hi)story of furniture design in Europe is not only written from a western European perspective, but is repeatedly told, almost exclusively, from a western European perspective, and tends to buy into a western Europe/USA science fiction narrative of the west as strong and sterling and righteous, and always defeating forces from outwith the west. Which is wrong. Is as fictional as Frankenstein. And needs to change. Yes, Afrofuturism is featured in Science Fiction Design but to what degree is Afrofuturism just another expression of North American culture and society? Just an expression of an, in the USofA, popularly perceived primacy of the culture and society of the USofA, albeit from an alternative perspective? But that, dear reader, is a discussion for another day.

The discussion for today is the relationships between design and science fiction, design as science fiction, science fiction as design, on the relationships between and developments of human society, science fiction, science reality and (furniture) design over the past century and a bit, a discussion that through the varied and various perspectives Science Fiction Design allows you to approach it from is also an invitation to approach differentiated perspectives on the (hi)story of furniture design; Science Fiction Design very neatly using the relationships around which its narrative is constructed to enable, empower, a more discerning approaching of the (hi)story of furniture design, that expanding of vistas via travelling unfamiliar, indirect routes that good science fiction facilitates.

And in doing so Science Fiction Design allows one to appreciate that in terms of furniture design there is no such thing as science fiction design: science fiction is fiction, design is reality, science fiction (furniture) design is an oxymoron.

And in being an oxymoron, a rhetorical device, not only allows you to effortlessly move beyond the presented themes and continue your exploration in other realms, but also underscores that while science fiction design isn't a thing furniture designers can employ science fiction as a tool in their design practice, can employ science fiction as a means to advancing the questioning on which their work is founded.

A true science fiction chair is surely a Marcel Breuer's 1925 vision of sitting on "einer elastischen luftsäule", "a resilient column of air", which is as impossible as flying to the moon, but which he almost realised, and which we are getting ever closer to experiencing; or the Sketch furniture by Front, works in which, if one so will, you draw your own tangible furniture in intangible space, and which while examples exist, isn't yet at a stage that it could be called a thing, but is moving in that direction; or the Space Colony and Space City projects developed by Fritz Haller in the 1960s, science fiction, extraterrestrial settlements of which Georg Vrachliotis once opined "in principle Fritz Haller went to space to be able to think better about earth"; liberated his questioning about the structuring and organising of life on earth from the limitations and fragilities and vagaries of the planet we all call home in the hope of finding new approaches to them. Or the numerous projects that populated the exhibition Konstantin Grcic. New Normals at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, those speculative proposals by Grcic as to what could, potentially become the normals of the future without undertaking any consideration on the whys and wherefores, but assuming future generations would intrinsically know, and that because technology, science, engineering and human society's understandings of itself and its environments will have moved on, as it invariably will, from where they are today; and a rapidly approaching of such Grcician normals that can be appreciated in Science Fiction Design in the form of the Scorpion Computer Cockpit from Cluvens, a lounge chair, a TV lounger, for computer gamers, that finds a very strong echo in two of Grcic's normals. Whereby one hopes that human society will one day be in a position to develop more meaningful uses for novel technology, science, engineering, can find more meaningful expressions of Grcic's open-ended questioning, than an overly aggressive room-within-room to immerse yourself in a first-person shooter, a work that stands so diametrically, and informatively, juxtaposed in Science Fiction Design to Panton's immersive rainbow. ¿Or is that the lesson one learns from Scorpion as a new normal, and also from the World Wide Web as a normal normal, and from 1950s aluminium as an old normal, that as a species we're brilliant at developing the novel, rubbish at employing it?

An ever closer movement towards Grcic's New Normals, an ever closer movement towards flying cars, towards Haller's space habitation, towards Čapek’s Roboti, towards Front's Sketch furniture, towards A.I. controlled decision making processes, towards Breuer's resilient column of air, towards the Mine in the Moone, towards a Mine in the Moone staffed by A.I. (em)powered Roboti, etc, etc, that reminds that science fiction needn't become science reality, things to come needn't be things from science fiction; it's OK for science fiction to remain science fiction, it was a vision someone once had in a film or a comic or a book or a play or an exhibition, is a vision that arose in a cultural context in a moment of human society's understandings of itself and its environments, in a moment of human society's desire to liberate itself from the limitations and fragilities and vagaries of the human being, and of the planet we all call home, there's no law that says it must one day become a thing. But it could be good, positive, meaningful if it did. Could help advance human society if it moved from fiction to reality.

The trick, we'd argue, is not to blithely accept things because they were once in science fiction; is to ensure that developments in human understandings of itself and its environments are not directly linked with developments in technology, science, engineering but occur in context of such developments, albeit with a wider view, and thereby enabling a critical questioning of the novel technology, science, engineering and the solutions it proposes. To question if we want the solutions it proposes. Or should we leave them in the realms of entertainment. That decision we also must make in context of ego driven politicians. We can leave them in social media, we don't need to bring them into the real world. Don't need to make intangible social media tangible.

That choice is ours. We are all the designers of our social, cultural, economic, spatial realities. Or are if we choose to be, rather than leaving it to others.

Through encouraging and empowering you to reflect on and critically question science fiction design, the relationships between science fiction and design, as well as chickens and eggs and oxymorons, Science Fiction Design is an invitation to develop a more robust framework for better distinguishing between science fiction and science reality, for appreciating what is fiction and what is reality in terms of science, and thereby for making more discerning decisions between science fiction and science reality. Which is not unimportant in 2024.

And through encouraging and empowering you to reflect on and critically question science fiction design, the relationships between science fiction and design, as well as chickens and eggs and oxymorons, Science Fiction Design is also an invitation to reflect on and critically question other popular narratives of furniture design; to reflect on and critically question 'Scandinavian furniture design', 'Bauhaus furniture design', 'Mid-century furniture design', 'Postmodern furniture design' and all the other expedient pigeonholes we've chiselled into furniture design for ourselves over the decades, and which while not necessarily oxymorons are as fictitious as science fiction, are the results of processes of human imagination, are a narrative that has built up over the decades at the active interface between culture and commerce, are components of a conditioning through association and the regular medial repetition of those associations, and have become popularly accepted as ideals worth striving for. Like flying cars.

Thus through encouraging and empowering you to reflect on and critically question such pigeonholes Science Fiction Design is also an invitation to develop a more robust framework for better distinguishing between furniture fiction and furniture reality, for appreciating what is fiction and what is reality in terms of furniture, for making more discerning decisions between furniture fiction and furniture reality, and thereby to approach better appreciations of the distorting and skewing of the relationships between furniture and society, between furniture and culture, such furniture fiction occasions, and which thus, arguably, makes blithely accepting the necessity of furniture reality becoming furniture fiction as dangerous for the future of human society and culture as the blithe acceptance of the necessity of science fiction becoming science reality.

That while science fiction and furniture fiction can serve useful purposes, can be an entertaining distraction, we needs must live in reality if we want to leave behind the limitations and fragilities and vagaries of the human being. And if we want to make the planet we call home one we want to live on rather than one we long to escape from.......

Science Fiction Design: From Space Age to Metaverse is scheduled to run at the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Charles-Eames-Straße 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday May 11th.

1see Carsten Thau and Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, Architektens Forlag, Copenhagen, 2002 As ever while there is something truly delightful in the idea of an Arne Jacobsen being “frightened” by an expanded polystyrene, we tend to believe it is more a case that he had extreme respect for and misgivings about his ability to work with the novel material, rather than an actual fear.

2As previously noted, the SAS Royal was very much intended as an American oasis in downtown Copenhagen in context of SAS Airlines expansion of it programme of flights to the USA, and certainly the architecture is very much deliberately formed in an American context, is meant to look as if it could be in New York or Chicago, but that doesn't necessarily mean objects such as the Egg were developed in context of creating a 1960s America in Copenhagen. And we'd argue the Egg wasn't developed in such a context. But that is all also open to discussion, and themes for another day.

3Observant readers will have noted we dropped Luigi Colani from that aforementioned list of interior concepts of the 1960s and 70s and reduced that list to Colombo and Panton. As in so many spheres Colani needs must here be considered separately, and at greater length than we can here, save to note that while some of the ideas Colani developed must without question be considered as based in and on science fiction, a lot was very much using science reality to form interiors as he conceived contemporary interiors should be. Which is what Colombo and Panton did.

4We're clearly referring here to those imaginary hostile residents of other planets and galaxies that abound in, and are so central to, science fiction. Which is equally clearly far too simple a view to take. But one we take for reasons of rhetoric. One should never forget that the enormous costs of the Space Race meant the money that was spent on rockets and moon missions of the 1950s and 60s couldn't be spent on social, education, health et al projects in 1960s Soviet Union and 1960s America, a 1960s America not without its social problems and tensions. Not everyone in 1960s America was fully behind the Apollo missions. See, for example, Gil Scott Heron's 1970 poem Whitey on the Moon. A poem that, yes, can also be considered in context of Afrofuturism. Which is fun to do.

Further details can be found at www.design-museum.de