In 1998 the then, German President, and native of Bavaria, Roman Herzog opined, "In München sind Lederhose und Laptop eine Symbiose eingegangen", 'In Munich, lederhose and laptops have entered into a symbiosis'.

One of innumerable partisan puffs for the Freistaat over the decades by Bavarian politicians; but also a very neat political statement implying that the popular image of Bavaria as being all about mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms, was no longer valid. That Bavaria had changed, certainly was changing.

With the exhibition Ois Anders: Major Projects in Bavaria 1945 - 2020 the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Regensburg, explore and discuss developments in Bavaria since the second half of the 20th century, and in doing so provide for wider reflection on not only change processes, but how we all view not only Bavaria, but the world around us in general.......

An exploration and discussion that opens in the late 1940s/early 1950s and the necessity, the primacy, of housing provision following the destruction and lunacy of the 1939-45 War, housing provision that, and as also noted from Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, often involved transforming spaces and complexes erected for War, and for the terror and violence and horror of the NSDAP, into housing for both those who had lost their homes as a consequence of the War and for those refugees and displaced persons arriving in the wake of of the War, and also those transported from elsewhere during the War years as forced labour by the NSDAP who choose to remain; a process that Ois Anders: Major projects in Bavaria 1945-2020 helps elucidate via, for example, the (hi)story of the Sankt Georgen munitions plant near Chiemsee, where, as one learns, chemical weapons were prepared and stored, and which following the end of the War, and following a thorough physical cleaning, physical decontamination, was used for housing and, essentially, became the contemporary town of Traunreut, one of five so-called Vertriebenenstädte, Displaced Persons' Towns, established in Bavaria as part of that post-War response to the need for housing, for all in context of those who had been forced, enslaved, to work for the NSDAP. Other Bavarian Vertriebenenstädte including Neutraubling on the south-eastern edge of Regensburg established on the site of a Messerschmitt factory or Waldkraiburg to the east of Munich which, as with Traunreut, was once a chemical weapons site.

If a discussion on the necessary post-War rehousing in Bavaria that, and in contrast to Power Space Violence, makes no note of the fact that the rehousing, the construction programmes, wouldn't have been necessary without the racist warmongering of the NSDAP; rather it's presented very much as just something that happened along the path of (hi)story, one of these things any region and country, inevitably, has to deal with in the course of time. And while, no, one needn't, shouldn't, keep beating oneself with a stick, a little context is never awry, and certainly not in context of the sort of discourse on recent (hi)story Ois Anders undertakes, and not least when one thinks of the leading role the authorities in 1920s and 30s Bavaria played in assisting and aiding Hitler's rise, including through their incompetent, and self-centred, arrogant, undemocratic, handling of Hitler's 1923 attempted coup. Context is always important, in (hi)story and in the now.

Which is also all another way of saying, Ois Anders — whereby, yes, you're right, we should explain the title, and will attempt to do so without getting lost in the labyrinth of translating Bavarian into German and into English... Ois Anders is, more or less, Bavarian for it's all/everything's different/changed/not as it was, it describes a change from a previous condition — Ois Anders cuts straight to the chase, it has no introductory chapter, a missing chapter which, as we'll argue in a couple of minutes, would have been more than useful.

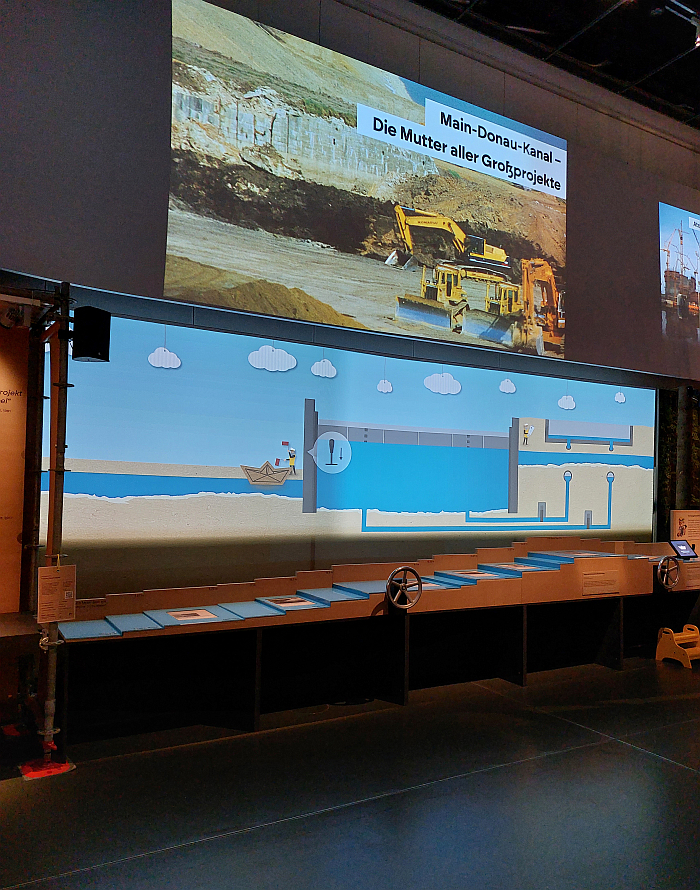

From the challenges of the immediate post-War years Ois Anders moves on to approach its central theme(s) through 8 of the Major Projects of its title, including, for example, the Main-Danube Canal, a project long, centuries, in planning that was realised between 1960 and 1992, that flows from (near) Bamberg in the north to (near) Kelheim in the south, and which Ois Anders notes, extols, is "ein Triumph der Technik über die Natur", 'a triumph of technology over nature', a formulation to which we will shall, must, also return; the Bayerischer Wald national park, established in 1970 as the first national park in Germany, and whose development, controversies, debates and legal wranglings provide interesting insights into the differing associations, differing understandings of our relationships, with the natural world different communities have, and also reinforces that, and as with the discussions undertaken by and from, for example, The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture at the Architekturmuseum der TU München or Die Stadt. Between Skyline and Latrine at the smac – Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz, planning is always about committing to using a space for one function that tends to negate, certainly impact upon, the possibilities of other functions, with all the problems, and responsibility, that invariably brings with it; controversies, debates and legal wranglings, if of different, if just as informative and instructive, kinds, also existent in the planning and development of the so-called Isental-Autobahn, a section of the A94 motorway between Pastetten und Heldenstein to the east of Munich, and specifically in context of the route it should take to link Pastetten und Heldenstein, controversies, debates and legal wranglings approached in Ois Anders through a wall of ring binders that chart the legal and political milestones of those processes, which is a very neat bit of exhibition design. And comment on German administration systems and fetishes.

And controversies, debates and legal wranglings that also define the narrative of the planning and development of Munich Airport on the Erdinger Moos to the north east of the Bavarian capital, a discussion that brings forth the surprising information that tea was once grown on the Erdinger Moos. Yes, tea in Bavaria. There's even a photo of tea being cultivated near the former town of Franzheim, one of several communities displaced, dispersed, demolished, Städte vertrieben rather than Vertriebenenstädte, to enable construction of the airport, and also the presentation of an actual tool for harvesting tea. Bavaria, it appears, is not just mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms, but also tea plantations.

Until that is you look more closely at the photo, and the harvesting tool, and realise that it's not Camellia sinensis that's being cultivated and harvested, but Mentha × piperita, peppermint. A distinction not made in Ois Anders well worth remembering when ordering tea in Bavaria: if you don't make the distinction that which you are served could be sauanders to that which you expected.

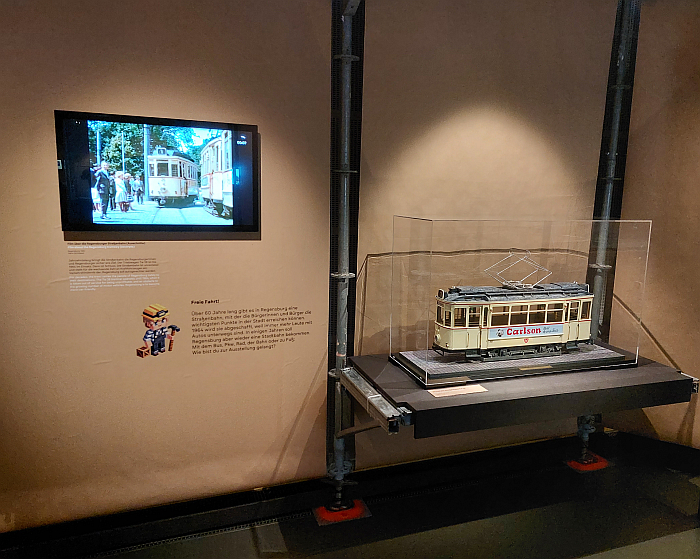

In addition, and arguably given the location of the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte only polite and sensible, or given the physical location of the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte only polite and sensible, the management and administration are based in Augsburg, ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ , there is a short chapter devoted to post-War developments in Regensburg, including mention of the trams that between 1903 and 1964 rolled through the streets of the city, and which some enlightened 21st century Regensburg citizens sought to reintroduce; but trams which a majority of 21st century Regensburger, for reasons we can't begin to compute, recently rejected in a local referendum. And while it could be considered tragic that you have to visit a museum of (hi)story to see a future orientated urban transport system in operation, as oft noted in these dispatches, the best solutions to any contemporary challenge often exist, we just need to see them through the fog of our opinion. And through our fascination with the novel.

Ois Anders ends, or rather doesn't, with questions of the future; those questions that needs must be approached as to how not just Bavaria, but by extrapolation we all, move forward from here, as we move through the 21st century towards, hopefully, the 22nd century. Questions whose necessity, urgency, is regularly underscored and highlighted in the course of Ois Anders including, for example, a comparison made in the first chapter between the ca. 700,000 houses that were needed in Bavaria in 1947/48 and the not all to dissimilar number that current projections predict will be needed in Bavaria's 5 largest urban centres by 2040, with the obvious extrapolation as to what that means for the whole of Bavaria, or by the expected doubling of the passengers passing through Franzheim Munich Airport by 2050, or by the currently in progress so-called sanften Ausbau, gentle/sensitive/unobtrusive/careful development, of the Danube between Straubing and Vilshofen to the east of Regensburg, a component of improving the navigability and accessibility of the Danube for cargo ships. And which reminds that we promised to return to the 'triumph of technology over nature' the Main-Danube canal represents. Which we shall do shortly.

A future which the curators see as one whose path will be defined by how we approach questions such as Where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises? Questions that as one can appreciate in the course of Ois Anders either weren't always approached in the late 20th century, or were approached in contexts and manners and from perspectives that are highly informative and instructive in and for not only how we got to where we are, but in our formulation of those 21st century questions we must approach.

As an exhibition, as a discussion on the development of the human-built environment in post-1945 Bavaria, Ois Anders' focus is one very much on infrastructure projects such as motorways, power stations, airports et al, and not, for example housing developments, or sport, social and cultural projects. Which for all we fully appreciate that in doing such Ois Anders very much keeps its focus on the juxtaposition of the mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms with which Bavaria is popularly associated and the 21st century with which it isn't always and thereby placing the two in dialogue with one another by way of allowing one to approach a critical consideration on and analysis of the implied dichotomy inherent in Roman Herzog's symbiosis, it is, for us, a little short-sighted as a perspective; for, not only does it tend to separate the need for many of the projects discussed in Ois Anders from the urban centres who are often that need, be that the centres of commerce and industry that need transport infrastructure or the densely populated urban centres whose residents are most in need of ready access to less densely populated spaces with appropriate infrastructure for their temporary stays, nor only ignores that in all probability the greatest growth in coming decades will be the urban centres thus the largest pressure on Bavaria as a whole will come from the increased demands of those urban centres, including increased demand for housing and services in communities near large urban centres by those seeking a home outwith the pressures and noise of the urban centres, albeit with infrastructure to allow then to quickly travel to those urban centres thereby adding to the pressure and noise from which they fled. But also the focus on infrastructure projects does tend to restrict access to many of the considerations that are necessary to enable us to approach the most meaningful formulation of the questions we need to pose in that it ignores a large number of contexts in which major building and development projects not only arise but for all subsequently exist upon their completion and thereby, inevitably, impact on communities, regions, societies as a whole.

For example, and while it is always rude, and a bit arrogant, to bemoan what isn't in an exhibition others more knowledgable and experienced than yourself have invested time and effort in curating, there is sadly no mention of Neue Heimat that housing association who in the first half of the period under review developed thousands upon thousands of apartments and homes across Bavaria, indeed across West Germany, including, for example, and amongst others, the Königswiesen estate in Regensburg, the Langwasser estate in Nürnberg, or the Parkstadt Bogenhausen and Neuperlach estates in Munich, and thereby contributing greatly to the relieving of the housing problems in the major urban centres in the immediate post-War years, and through the subsequent years of economic boom and bust. But also created a lot of high-rise estates, for all high rise estates on the edge of cities, thereby not only contributing to structural changes in those cities, and increasing the demands of the cities in terms of resources and services, but also creating spaces and constructions that with time required very specific, and invariably very expensive, inspection and maintenance programmes, and which when not properly cared for, physically, socially, culturally, can become problems in their own right. Thus a Neue Heimat who can enable one to better incorporate questions such as where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises? into questions on a future Bavaria that, in all probability, won't see the creation of rural new towns such as Traunreut, Waldkraiburg or Neutraubling, it's not something you can imagine any Bavarian government asking Bavarians to accept, yet will also be keen to avoid large peripheral high-rise housing estates; but a future Bavaria that will need, according to the data presented in Ois Anders, for example, ca. 55,000 new dwellings in Regensburg by 2040. Where and how should they be constructed? How should they be supplied with power, water, and other essential services? And how are people meant to get to and from them without trams?

Similarly there is no mention of the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, and while, yes, there was recently a lot of attention on the 1972 Olympics in context of the 50th anniversary, and one can overindulge in anything, it was a project initiated by way of helping West Germany re-establish itself in the international community after the 1939-45 War, and in helping Munich present itself as contemporary city with its finger on the pulse on the future, or at least that was the plan, and which provided the city in addition to sports and concert facilities an awful lot of housing, and the Olympia shopping mall thanks to Neue Heimat: and also provided a legacy that at times is very expensive, and intensive, to maintain. And thus a 1972 Olympics which allows for important reflections on staging such large events, on constructing for large events, and also by extrapolation on planning and constructing any large scale intervention relative to the size of the location in which it is realised for a single purpose, for all when the motivation of that purpose is more prestige, representation, symbolism and less spatial planning, but which will remain once that purpose has ended. Which could also be, for example, the staging of a state or national horticultural show, the staging of a major building exhibition, or the construction of a business park, a trade fair complex, an office complex, a factory, etc, and thus a 1972 Olympics that can enable us to better incorporate questions such as where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises? into the formulation of our questions.

Nor does Ois Anders find space to do more than mention the existence of Regensburg University, regrettably, because for all that Regensburg is without question its Cathedral, its Middle Ages urban planning, the Danube, the spatial planning horror of Arnulfsplatz, its bridges, its innumerable breweries, its 400,000 Pizzerias and its coffee kiosk, ¿what the kiosk in Regensburg?, yes.... kiosks technically, and the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Regensburg is also its university. A campus crafted from concrete and grass, a composition whose stability relies on the tensions between concrete and grass, an ode to the utopic visions of Japanese Metabolism in the Oberpfalz, or is in our reading of it but may not have been conceived as such, that is not only interesting for the positions to architecture and construction and planning and space it embodies, but also because of the contemporary problems arising from the the visionary future it once offered and promised to achieve, those problems of 1960s and 70s utopian architecture and urban planning and the questions of how we move on from them that are important in context of our own 21st century utopian architecture and urban planning. And thus a university campus which can help us to better incorporate questions such as where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises? into questions of the viability, and durability, sustainability, the ecological, economic, social, cultural et al sustainability of an architect's vision. Which yes does bring us back to Neue Heimat and the 1972 Olympics.

And also a regrettable absence because, as the curators note, the establishment of the university in the mid-1960s was an important component of the structural developments in and of Regensburg and environs, helped, along with the opening in 1986 of the new BMW factory on the edge of the city which is similarly mentioned en passant in Ois Anders, and to which we'll add the unmentioned development from the late 1980s of the Universitätsklinikum Regensburg a little down the A3 from BMW, strengthen the economic base of Regensburg and environs, thus highlighting that not only infrastructure projects, such as say, for example, an urban tram network, are important in helping any region develop, but also culture, social and education projects play a not insignificant role, or can. And also allowing one to approach an appreciation that decisions about the development of the human-built environment shouldn't be based on the purely economic considerations that are at the core of many, ¿the majority? of the projects on which Ois Anders discussion is based, but our gaze must go further when considering where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises?

A need to shift the focus from the economic viability, impact and promise of the major infrastructure projects of Ois Anders' title and discussion that in another context is a recurring theme in Ois Anders.

Arguably a, the, key theme.

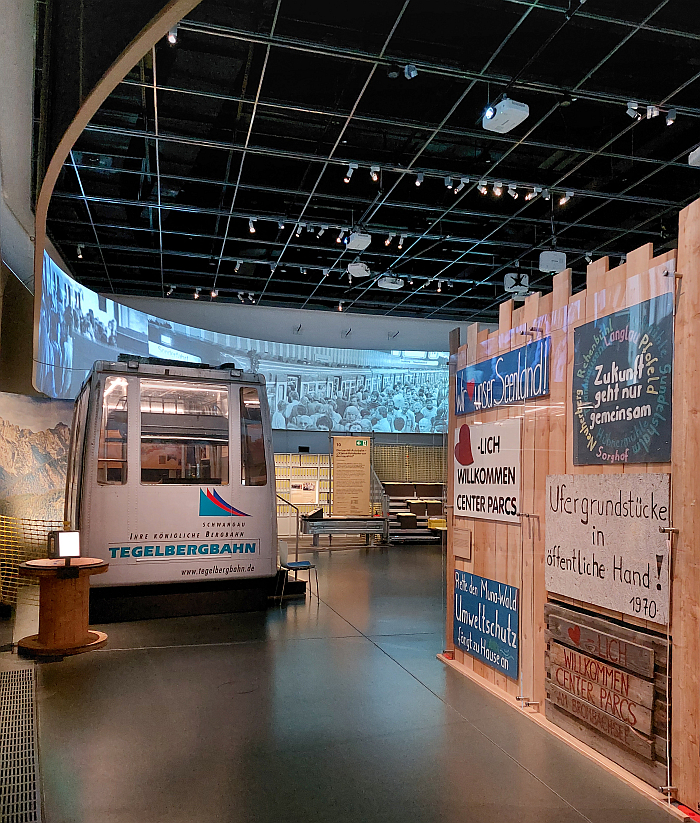

As you wander through and explore projects such as, for example, the expansion of tourism in the Bavarian Alps, including the construction of chair lifts and infrastructure for skiing, or the construction of Munich Airport, or the construction of the Main-Danube canal, you come to appreciate that such projects have their origins in an age, essentially, before ecology was a thing, not completely, as one reads such projects did have their opponents on grounds of the to be expected ecological impact, but that was very much fringe groupings, groupings the greater majority placed outwith conventional society and thus tended to ignore, disparage; Ois Anders helping explain that the second half of the 20th century was very much an age when the focus was fully on economics, when the pros and cons, risks and benefits, of any project were measured primarily, and self-evidently, in Deutschmark and jobs. Arose in an age that was very much about nature as being subservient to humans, nature existing to serve humans, an opinion very much present, celebrated, in the assessment by Ois Anders of the Main-Danube Canal as 'a triumph of technology over nature', an outrageous claim to make in the 21st century, a claim that is rooted, steadfastly, unreflectively in the second half of the 20th century, and the first half of the 19th century, sees the engineer as a God forging new realities, much as the AI developer of today is triumphing over humans on progress's steadfast march forward......

.......ignores out of hand, openly devalues und negates, the information we have today about how canalisation and the designing of rivers to aid the navigability and accessibility of shipping affects not just rivers but their immediate vicinity; devalues und negates what Ois Anders itself tells you about the irreversible ecological impact in the Altmühltal caused by the canal, the consequences of that 'triumph', ignores that Ois Anders explains why those consequences, that 'triumph', represent a defeat for human society, and also tends to skip over that, as Ois Anders also notes, the canal's contemporary use is nowhere near that which it was planned to be, which poses the question as to the value of the 'triumph'. And which also tends to question the motivations of a construction project the, then, Federal Transport Minister Volker Hauff, apparently, referred to in the early 1980s as the "dümmsten Bauwerk seit Babylon"1, the 'stupidest building project since Babylon", where was the emphasis? Which requirements had priority? Was a good compromise approached? In Babylon and/or Bavaria.

And also ignores that a sanften Ausbau, be that of a river, an alpine valley, a moorland, a stretch of coast, of which Bavaria admittedly has none, is a bit of an oxymoron; the development of a river to improve navigability and accessibility of shipping can have relative degrees of impact, but can only have a relatively soft, never a soft, impact. Softer is always possible.

However, thoughts on the development of the Danube between Straubing and Vilshofen, and the (relative) lack of ships on the Main-Daube canal, which also lead you, as you wander through Ois Anders, engaging as you go with its various and varied themes, to an appreciation that for all that in the 21st century there has to be not only an ecological component, and also a cultural and social component, to considerations on and planning of any large scale human intervention in nature, there are also good and convincing arguments that can be made for an increase in the amount of goods transported in Europe by rivers as a component of responding to our current climate emergency and resource overuse, yes, yes, assuming we can solve the problems of the fuel used by such river cargo ships. And thereby of the need to make rivers such as the Danube better navigable and more accessible for cargo ships. Where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises? ¿sanften Ausbau? ¿And if we can't?

Complexities of the balance between the natural world and the human-built world, the balance between the demands of human societies and the demands of non-human societies, the demands between commerce and the natural world, between commerce and culture, also neatly elucidated in the various and varied stand points on and to the creation of, and subsequent realities of, the Bayerischer Wald national park, a reinforcing that there are innumerable definitions of 'forest' and of the function of a 'forest'. If one definition of 'forest' excludes, restricts, all others, where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises?

And complexities also, arguably primarily, elucidated in the brief discussion in Ois Anders on the river Lech and its ca. 30 hydroelectric power stations between Füssen and Augsburg, power stations which provide an awful lot of renewable energy for the region, but whose creation required large scale interventions in the Lech and which have turned a natural river of the sort Bavaria is popular mythologised as being primarily about in to an industrial tool for society, a further 'triumph of technology over nature'. And which one notes is and was a process that, more or less, begins with the creation of the Forggensee reservoir at the foot of the hill on which Schloss Neuschwanstein stands; a lake at the foot of a forested hill that for all it appears to scream 'Bavaria', is an artificial creation in the natural landscape for the benefit of human society, a 'triumph of technology over nature'. As is Schloss Neuschwanstein. And an intervention in the Lech that helps elucidate that just as there are innumerable definitions of 'forest' and of the function of a 'forest', so to of 'river'. See also the 'Danube'.

A reconstruction of, intervention in, the river Lech that can also be considered in context of the chapter Future Energyscapes within the exhibition Transform! Designing the Future of Energy at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, and its considerations on how we can integrate renewable energy production and distribution systems into the natural environment. Energyscapes also involved in the pro and contra debates around the construction of the nuclear power station at Gundremmingen to the west of Augsburg; nuclear power that while for some is an incalculable danger for the mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms of Bavaria, is for others their saviour. ¿Which do you prefer, a nuclear power station or dozens of hydroelectric power stations in a river?

Reflections on energy generation and supply Ois Anders very pleasingly and satisfyingly forces you to consider in context of the road, airport and waterway building projects on display, and the housing on display, construction and mobility being as they are responsible for some 60% of global energy demands; and which thereby, along with the tourism on display, reinforces that we only need to generate and distribute so much energy because of the need to power our contemporary lives, contemporary human society. What if we made changes to how we lived and consumed? What if fewer cargo ships were needed on the Danube? What if we needed less timber for construction and furniture? What if König Ludwig II and his fellow residents of Füssen had only one smartphone each? What if we accepted that is snows less in winter than it once did, and that we're the reason it snows less, and stopped making snow for tourists to ski on? What if the residents of Regensburg could travel by tram? Where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises?

Through forcing one to question the whats, wheres, whichs, and also the whys, wherefors and whomfors of the 8 featured infrastructure projects, their inter-relationships and their myriad connections to us all, Ois Anders is an instructive and informative exercise in helping us find our way forward.

Individually and collectively.

Within Bavaria and outwith.

A relatively bijoux exhibition, which no, doesn't fit in with how one normally perceives and understand Bavaria and Bavarians, Ois Anders presents its 11 succinct trilingual German/English/Leichte Sprache chapters in a scenography of recycled materials, something that is very much becoming a thing in exhibitions in Bavaria, museums in Bavaria, apparently, increasingly questioning where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises? in terms of exhibition design, which is to be welcomed, we hope also by exhibition designers; and via a wide mix of objects, contemporary TV snippets, photographs, documents, charts and interactive stations.

And, and most unfortunately, also via a series of films which at regular intervals appear above your head, from the roof of the temporary exhibition space, like the tidings of some herald of the Gods, but which rather than bringing great joy bring a narrator who shouts uncouthly at you, making it impossible to concentrate on the exhibits until the shouting ends, much as it is impossible to work on a train until the Start-uper in white sneakers and ear-pods stops shouting their game of Bullshit Bingo into public space, because they believe their ear-pods, and the unquestionable genius of their generic business idea, makes them invisible and inaudible. And a disagreeably shouty narrator who, in contrast to the largely neutral tone the exhibition texts present, the multiple perspectives the exhibition texts actively encourage you to take by way of approaching your own position on and to the myriad themes involved, is a little to ''aint Bavaria brilliant!!!' for our tastes, is a BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! little to focussed BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! on undertaking PR for Bavaria, that thing BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! a Roman Herzog and innumerable Bavarian politicians JOUR FIXE!!! JOUR FIXE!!! JOUR FIXE!!! before him and since have BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! specialised in, than adding to the discourses initiate by the BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! texts.

Whereby, yes, the claim the Main-Danube canal is 'a triumph of technology over nature' does sound as if it was penned by someone in the publicity department of the Bavarian Wasserwirtschaft authority, potentially the same department who decided a sanften Ausbau was an actual thing, or by a late 20th century conservative Bavarian politician, and not from the academic department of a museum. It's 2024. Not 1974 when triumphing over nature was still the raison d'etre of the human species, rather than the seeking of partnerships with nature, of working with nature that is, must be, the aim today. Part of any museum's remit is surely to reflect critically on what was. And to provide context to help us all better understand why then was then, what has changed since then, how then became this, and to encourage one to critically reflect if this is better or worse than then an how do we want that which is to come to be in comparison to then and to this.

And, and ignoring as best you can the shouty Bavaria fan... no, it's currently a pause between films, we can all relax and concentrate on Ois Anders ...the mix of exhibits, and variety of subjects approached, and the means of their approach, not only allow Ois Anders to largely achieve that, but also mean that for all Ois Anders is an exploration of the development of Bavaria since 1945 in context of the built environment and physical infrastructure, it is also very much an invitation for a differentiated tour through the (hi)story of Bavaria since 1945, a differentiated tour along part of that timeline followed in the museum's permanent exhibition; a Bavaria that in the period under review moved from being a largely agricultural region to an economic powerhouse....... which is another reason why an introductory chapter would be welcome, why a little more context would be welcome, not only to explain why the 1939-45 War left Bavaria in the state, and with the problems, it did, but also to explain where Bavaria came from before 1945, to explain the 'was' that became an 'is', explain how and why a Roman Herzog could claim lederhose and laptops had entered a symbiosis, including explaining the financial aid that flowed from elsewhere in West Germany into Bavaria in the early decades of Ois Anders timeline and thereby enabled, (em)powered the economic development of Bavaria. A fact we believe many Bavarians, certainly many Bavarian politicians are unaware of, have never been told. An introductory chapter could and would help.

A differentiated tour through the (hi)story of a Bavaria that at the start of the period under review was not only largely agricultural but was, on several fronts, the border between West Germany and Eastern Europe, was one of the easternmost outposts of western Europe, was physically, economically and politically on the fringe of Europe; a Bavaria that became more or less the physical centre of the new Europe, and one of the economic and political centres of the new Europe, following the events of 1989 and the slow eastward expansion of the EU... another reason for an introductory chapter... and thereby a reminder of the links between the political and economic developments of any region, community and society and not only the spaces and infrastructure they need and demand but how those spaces and infrastructure are realised, maintained and employed. And how the arguments for those spaces and infrastructure are framed. And how that all changes with time. And how the consequences of decisions we make change over time.

A tour that is also one through the shifting relationships between the constructed environment and the natural environment, of a change from an age when symbioses with nature were understood as being self-evidently parasitic to the mutualistic symbioses, or at worst communalistic, we strive for today; and also a tour through changes in appreciations of the human-built environment, of a shift away from appreciations of the human-built environment as being about structures and buildings towards the relationships that exist within those structures and buildings and how those structures and buildings influence and inform the further development of both those relationships and the structures and buildings, and thereby human society.

Or put another way, Ois Anders allows for various and varied reflections on the processes of change implied in its title and which it approaches in one context thereby enabling and empowering you to explore the rest on your own; including reflections on the fact that in all contexts ois werd si ändern, everything will change, and thereby allowing one to not only better reflect on the argument that everything must change, but for all that the course of that change isn't inevitable, isn't pre-defined, isn't fixed, we can all be part of it.

Which in itself is also a change from the immediate post-War decades that Ois Anders opens in when, as a general rule, designing change was the privilege of a much more limited group than it is today. A reality that also influenced how that group made its decisions.

And is a tour in whose course one becomes aware that there isn't and wasn't a symbiosis between lederhose and laptops, or between dirndl and digitalisation, in the period under review, rather there arose a coexistence between two projected self-images of Bavaria, one a continuation of the invented 19th century Bavarian identity, the tourist gaze identity, of lederhosen, mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms; the other a 20th century location marketing identity, a politician gaze, of laptops, mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms. Neither of which represents a complete truth, both of which are about trying to define Bavaria other than it actually is for specific purposes, as is brezn and biotechnology, radi and robotics, weisswurst and white sneakers, and the innumerable other alliterations a 21st century Roman Herzog has at their disposal. Tracht and trams.

Similarly, through viewing and engaging with Ois Anders you become aware that if there is a dichotomy in 'lederhose and laptops' then it's primarily in context of the directions of their view and their intent: Bavaria as lederhose is not only a view backwards but a view that arose in the 19th century by way of resisting change, was an attempt to deny that Ois Anders through linking up to an imagined Bavaria past, arguably, an expression of a retrotopia. Bavaria as laptops is an acceptance that Ois Anders, an acceptance that the mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms have been joined by other things that weren't there before. And thus a dichotomy in 'lederhose and laptops' that enables differentiated reflections on definitions of Heimat, homeland, a concept that is as undefinable as 'forest', 'river' or 'urban transport', but which each and everyone of us has our own definition of based on our own conditioned viewing of the world around us and the relationships therein. Views that aren't wrong but are no less complete than Bavaria as lederhose and Bavaria as laptops. A concept of Heimat that although but rarely physically present in Ois Anders, and when then, and very informatively, in political advertising, Ois Anders tending to imply that the concept of Heimat is a political argument, a rhetorical tool of politicians, more than an intrinsic component of the human being, which in itself is well worth reflecting on in our contemporary Europe, what if politicians didn't focus on advancing definitions of an indefinable Heimat....... a concept of Heimat that although but rarely physically present in Ois Anders can be located at the centre of many of the discussions concerning the 8 projects; many of the discussions are less about the projects themselves as about changes to the perceived Heimat as a result of the project, about an Ois Anders that for some is a danger for the Heimat and for others enhances that Heimat. Your forest isn't someone else's forest, but is the same physical area. Your river isn't someone else's river, but is the same physical area. Your urban transport network isn't someone else's urban transport network, but is the same physical space. Your Heimat isn't someone else's. And both are invariably based on a conditioned viewing of the world, neither being more truthful than Bavaria as lederhose or Bavaria as laptops, ¿Who's has priority?¿How do we formulate the questions? ¿How do we move forward?

Thus for all that Ois Anders is an exploration of Bavaria's move from an agricultural backwater to an economic powerhouse, and an invitation to reflect on our relationships with the natural world, on the condition of human society, on change as an inevitable component of existence, on Heimat and on mountains, forests, lakes, rivers and rugged herders on livestock dense alms, it is also a convincing argument for the urgent necessity of more honesty in discussions on the changes that are occurring and will continue to occur, for the necessity in less lobbying, less shouting of half-truths and dogmatic positions on social media, less BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!! BAVARIA!!!, less focusing on the unquestionable validity of your opinions as the basis for a discussion, less Heimat, a lot less Heimat, and more accepting that others have a point, often one worth considering, more accepting that there is more than one answer to the questions where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises?, and that ultimately we're going to have to settle on an answer, and that answer may exclude your answer. May mean graciously accepting there are no trams in Regensburg. Or power stations on the Lech. Or more tourists in the Bayerischer Wald. Or are other directions in which to position a blog. Accepting that every change ushers in new possibilities, raises new questions to be approached, allows new perspectives on where do we place the emphasis? Which requirements do we give priority? How do we achieve good compromises?

And thereby to approach considerations if the thing that needs must change, if the most urgent context in which Ois Anders, isn't us. Collectively and individually.

Ois Anders: Major Projects in Bavaria 1945-2020 is scheduled to run at the der Bayerischen Geschichte, Donaumarkt 1, 93047 Regensburg until Sunday December 22nd.

1* quoted in Ois Anders, for a little more context see also Karl Stankiewitz, Aussichten vom Turm, in Karl Stankiewitz, Babylon in Bayern. Wie aus einem Agrarland der modernste Staat Europes werden sollte, edition buntehunde, Regensburg, 2004. We haven't, as yet, been able to find the original source, but once we do, if we do, we will update

Full details can be found at www.museum.bayern/ois-anders