"A bútortörténet az általános művészettörténet és a művelődéstörténet egyik speciális ága" opined the Hungarian interior designer, furniture designer, editor and educator Kaesz Gyula in 1962, 'furniture history is a special branch of general art history and cultural history', continuing that 'its task is to acquaint you with the part of human creative work that creates the human environment and means of use. Through the individual objects, we get to know the age, the production and social relations, which determined the living conditions, aspirations, and struggles of the people who created and used the objects. The objects of the human environment are meant to satisfy various needs. From the way these needs are met, we can learn about the characteristics of the human environment of each age', adding that furniture, 'inform[s] us precisely about the development of each society's comfort needs, technical and artistic creative methods'.

And not just a society can be studied, according to Kaesz, through its furniture but also 'the tastes of their former owners. Hobbies, whims, thoughts and needs are expressed in the forms of furniture'.1

With the exhibition Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 the Walter Rózsi Villa, Budapest, invite you into the former home of Kaesz Gyula and his wife, the graphic designer, packaging designer and illustrator, Lukáts Kató where their furniture, and interior design, allows one to not only 'get to know' two interesting, important and informative 20th century Hungarian creatives, 'get to know' their tastes, hobbies, whims, thoughts and needs, but also allows one to better approach the development of furniture and design, the path of 'cultural history', in both Hungary and in Europe.......

Born in Budapest on July 13th 1897 Kaesz Gyula studied interior design at Budapest's School of Applied Arts, graduating in 1917, and in 1919 taking up a teaching post at his Alma Mater; we'll leave you to do the math yourselves as to what else was happening in Budapest between 1917 and 1919. A post at the School of Applied Arts Kaesz retained in various forms until his retiral in 1958, including serving between 1952 and 1958 as the institute's Director, a period that saw him introduce Industrial Design to an institution that is a direct forbearer of the contemporary Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, MOME.

And a Budapest School of Applied Arts where, we presume, he met the graphic art student Lukáts Kató, a native of Jászkarajenő, a village on the southernmost edge of Pest County, born on April 14th 1900, and who after initially enrolling at Budapest's University of Fine Arts switched, fatefully as (hi)story records, to the School of Applied Arts, graduating in 1925; a 1925 in which Kató and Gyula married, the formal start of a personal and professional partnership that through the canons of work they developed both individually and in cooperation saw them become two of the more important, informative, protagonists in the development of design in 20th century Hungary, specifically a Hungary that in the years 1925-1960 of the Walter Rózsi Villa's exhibition's title, experienced numerous events of fundamental importance to the 'social conditions' and the 'environment' in Hungary, and the 'living conditions, aspirations, and struggles' of Hungarians.

And a personal partnership that saw Kaesz and Lukáts live in various apartments across the Hungarian capital: beginning married life in 1925 on Erzsébet ter and ultimately, following five intervening flits, settling in 1949 at Petófi ter 3, but a stone's throw from their first apartment; a 5th floor apartment on Petófi ter with, by all accounts, a panoramic view from Pest across the Danube to Buda Castle.

And a 5th floor apartment on Petófi ter that Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 invites you to enter.

Or more accurately Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 invites you into a staging of Kaesz and Lukáts' original furniture in a different location, in a house, a villa, they never lived in. Which isn't exactly the same as being invited into their Petófi ter home, but pretty close, just without the views across the Danube to Buda Castle. And certainly no less museal than any other invitation to view historic interiors of those no longer amongst us. Nor does it detract from what one can learn on a tour through the rooms.

A tour that, essentially, begins, in a restaging of the Kaesz/Lukáts2 dining room, a space that on Petófi ter, and in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, features as one of the defining objects a 1935 sideboard by Kaesz in zebrawood, an example of that type of decorative wood that has more or less vanished from contemporary furniture but was once so omnipresent and which provided for ornamentation of furniture that rejected ornamentation. A zebrawood sideboard with an extendable shelf, or more accurately two shelves, which extend not just the sideboard but its usefulness, and atopped by a small vitrine, also in zebrawood, for glasses, coffee cups, trinkets, etc, and which, as the curators note, was a fashionable addition to sideboards in the Budapest of that day, was a 'whim' of the Budapest of that day, certainly amongst those in 1930s Budapest who could afford zebrawood sideboards atopped by zebrawood vitrines.

Much more reserved in its wood if no less expressive in its character is the 1930s serving/bar trolley by Kaesz that stands next to the sideboard, a work defined by the encasing of the uppermost section behind six sheets of glass thereby making it as much as vitrine on wheels as a trolley, and a composition in glass that tends to imply that is as much for presentation as for function, or perhaps better put, tends to imply it is a trolley whose function is presentation as much as aiding and abetting socialising; a clear expression of function that is not instantly mediated by Kaesz's late 1930s radiogram, a characterful but otherwise anonymous wooden box that reminds of a Luigi Colani's complaint that the staff and students at the HfG Ulm produced anonymous grey plastic boxes whose function was hidden, as is Kaesz's radiogram's function. Or would be hidden were it not for the inlay by Lukáts depicting numerous musical instruments that explains what the box is and does; inlay that is another expression of ornamentation that rejects ornamentation, being as it is graphic and not ornamental; inlay that was, when not widely used in the early 20th century, was more widely used than (hi)story has recorded, certainly in works expressive of a committent to craft in an age of rising industry, or a commitment to musical instruments in an age of electric radiograms. And inlaid musical instruments, including a violin and clarinets, or possibly saxophones, that both in technique and depiction introduce a folkloric in aspects of Lukáts' oeuvre that is regularly encountered in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960.

Other aspects of Lukáts' oeuvre being elucidated in and by the curtains and wallpaper in the dining room staging printed with a pattern developed by Lukáts in 1936 under the name Napraforgó, Sunflower, a name that instantly takes you from the Walter Rózsi Villa, a strikingly Modernist, Le Corbusier inspired, mid-1930s work by Fischer József and Pécsi Eszter to Napraforgó utca, Sunflower Street, that unofficial official Hungarian Functionalist Modernist building exhibition, street, developed in 1931 in north western Budapest and featuring works by over 20 Hungarian Functionalist Modernist inclined architects, including Fischer József, almost certainly in cooperation with Pécsi Eszter; a Napraforgó pattern that, as far as we can/could ascertain, doesn't contain a single actual sunflower but which with its stylistic flowers, leaves, fruits and birds is an enormously sunny work, positively shines out at you, in all of the colour combinations and contexts in which it features in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, and in which it was printed during Lukáts' career. A pattern whose differing agency depending on hue and material offer an excellent introduction to how colour and material interplay in our perception of the physical world. And a work which in its innocent, almost naively so, stylistic depictions of nature, and its very free and easy relationship with geometry, speaks very much of textile design in the 1930s. And also of the 2030s. Arguably also the 2130s.

And also speaks of something, someone, to which, whom, we shall return.

A mix of projects to be found not just in the dining room but throughout Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 by Kaesz, Lukáts, Kaesz and Lukáts which underscores that their interior was theirs, as in not just assembled and composed by them, but self-designed, populated by their works, by their expressions of their tastes, hobbies, whims, thoughts and needs, by their 'creative' responses to the realities, demands, questions of period under investigation. And underscores that their interior was an active cooperation between two creatives.

A cooperation between Kaesz and Lukáts delightfully reinforced by the ca. 1940 dining bench, a truly fascinating and communicative object, the bench itself designed by Kaesz, the upholstery by Lukáts, if in a green hued ribbed velvet fabric and not the green leather on display in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, a leather that is consequence of a 1980s renovation, and which may or may not have been authored by Lukáts. We very much hope it was. For it very much completes the object. Even if we are admittedly still unsure if we prefer the dining bench with or without the backrest upholstery. One of those questions we may never find a satisfactory answer to. Black and white photos of the bench and chairs in the green hued ribbed velvet upholstery helping you approach Lukáts' original, 1940s, intention.

A ca. 1940 Hungarian dining bench that is an example of a furniture genre that was once popular, once very popular if traced back to the Middle Ages; and a genre that is becoming popular again today, not least in context of our ever more compact apartments that are increasingly being asked to serve simultaneously as home and office, and the need inherent therein for furniture objects to perform more functions, to contribute to a space in more ways, than was the case in more recent decades. A ca. 1940 Hungarian dining bench that is very clearly divided, delineated, into four separate seats, or perhaps better put, a ca. 1940 Hungarian dining bench that lets you know it is four of the dining chairs which accompany it around the dining table, joined together to form a dining bench, thereby creating an effortless unity and clarity, and parity, across the dining furniture. Allowing a calm to settle around the table. And a joining of four chairs to make a bench that reminds very much of Willy Guhl's more or less contemporaneous Stuhlbank which is and was separate chairs intended to be aligned to form a bench, and thus two alternative 1940s takes on the side chair arising, more or less, as a subdivision of the benches of yore, of the relationship between the bench and the chair, of a desire for a path back from the chair to the bench.

And a deliciously engaging, inviting, undemanding and visually weightless work that as you enter the dining room staging you initially read as 1950s Scandinavia, you do that thing Jacob Strobel did when he first met the EW 1192 by Horst Heyder; and you read it as Scandinavian primarily because that's what we're conditioned to do, that's how the popular telling of furniture (hi)story, the popular telling of that 'special branch of general art history and cultural history', tells you how to read such a work; and studying it in detail, in context of that conditioned reading of furniture (hi)story, it is very hard to make an argument that it isn't 1950s Scandinavia. Apart from the fact you know it is 1940s Hungary.

And what does that teach us all?

And what does that mean we all need to do?

And how delighted were we to make the acquaintance of such an elegant, communicative, charming, lesson.

And how delighted were we to make the acquaintance of the modular shelving and storage system upstairs in the staging of Kaesz Gyula's office.

A modular system designed by Kaesz in 1929, thereby placing it at heart of Functionalist Modernist positions of the period, directly on the pulse of the period; for while modular bookcase systems were known in the 19th century, were a thing in the 19th century, and from the early 20th century were a thing in Hungary thanks to the system introduced by the manufacturer Lingel, Kaesz's must count as one of the earliest systems developed in context of the Functionalists' fascination with standardised modular construction systems, be that in context of furniture or architecture. And while 19th century systems are generally only for books, Kaesz's features in addition to units for books, book units featuring, one notes, height adjustable shelving thereby making them more responsive to the differing book sizes of the period than the unresponsive 19th century bookcases intended for folios, also includes units featuring cupboards, drawers and compartments with drop-down doors for folders and the like, thereby allowing for the development of solutions to 'satisfy various needs', allowing a myriad individual solutions to satisfy the myriad individual 'needs' of any society. Or would do if commercially available, which we don't believe it was. Much more it was designed by Kaesz Gyula to 'satisfy various needs' of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató.

Needs including what the curators describe as Kaesz's "extremely orderly and meticulous" character, he was, apparently, an individual with a 'whim' for order, a 'need' for order, and whose furniture can, in many regards, be considered as a tool for achieving order, something also referenced in context of the zebrawood sideboard where one is told, but regrettably not shown, that the interior is and was "elaborately designed for tableware and table linen", and which one needs to see to fully appreciate. And a use of furniture as a tool for achieving order that reminds not only of the development of, the raison d'etre, and the positions that underscored the so-called Efficiency Desk of the early 20th century, that effortless expression of the optimisation and standardisation that are so regularly elements of Functionalist Modernist works, but which also reminds very much of Kaesz's contemporary Kaare Klint, that Grand Doyen of Danish Modernism, who was similarly desirous to bring unbreakable order to the world, or at least to interiors, through furniture design. But whose bookcases would have been designed in feet and inches, and for storing folios, rather than that metric nonsense employed and encouraged by Kaesz.

A use of furniture as a tool for achieving order that can also be gleaned in the pages of Kaesz's 1962 book Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat, Get to Know Furniture Styles, where Kaesz notes that 'expediency and the best possible usability of today's wardrobes is manifested, for example, in the careful interior'3, and in which context he highlights a wardrobe presented by Giuseppe Gibelli at the 1936 Triennale Milano whose interior not only has space for all your clothes and accessories but is fastidiously planned, "elaborately designed" to paraphrase the curators of Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, leaving the user next to no option but to acquiesce to Gibelli's system. And also highlights a truly fascinating object described, tantalisingly, as 'The most practical dish cabinet, made in Sweden', and which appears from the sketch, Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat features an awful lot of sketches, to be a collection of trays for storing crockery, cutlery et al. Trays which you remove from the cabinet, carry, with the crockery, cutlery et al, to where they are needed and then bring back and replace. Which is very much an industrial approach to organisation and storage, in an object, one presumes, we've been unable to find an actual example, crafted in finely carpented wood. And a tray-based storage system which while allowing for a very strict degree of organisation, doesn't appear to be a particularly efficient use of space, unlike Kaesz's modular system which leaves the organisation up to you while offering a very efficient use of space, thereby allowing for reflections on the relationships between efficiency and organisation, that relationship that needs must be reflected on more than it generally is. And needs must be reflected on with a greater veracity in context of the fabled Germanic organisation and efficiency, than it currently is.

And a desire for order that can also be understood in Kaesz's drawing cabinet, a work that is also, essentially, a modular construction, a work whose that expresses itself graphically not via inlay but through the handles, and a wooden cabinet which stands on metal legs, as does Kaesz's desk; metal legs which don't initially attract your attention, you've seen wooden desks and cabinets with metal legs, that's something your familiar with, your focus is elsewhere. But then you start considering the metal legs in context of not only the preponderance of wood, carpentry, craft, folklore, to be found throughout Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, but also in context of the general lack of metal furniture, certainly a lack of steel tube furniture, in a presentation covering the years 1925 to 1960 being staged in a strikingly Modernist villa developed by two of Hungary's more strikingly Modernist architects and engineers.

And then you look at the chair that stands in front of the desk with its implication of a voluminous representative lounge chair, albeit an impression negated and resisted by its compact scale, its desire to be part of its environment and not to define that environment, by the spindle backrest which tells you it wants to be a Windsor chair, and the refusal of the armrests to join with the front legs in a solid block and instead curving off early to create more freedom for the sitter, and then you begin to reflect on the high-back armchair in front of the modular storage system, on the armchair that stands next to the radiogram, on the bed in the room next door, the dining bench, the Napraforgó curtains and wallpaper, and as you do so the aforementioned something, someone, raises its, their, head: Josef Frank.

Wandering through Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 is to increasingly appreciate that there is very much a comparison to be made between many, not all, but many, of the works by Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató and the work of Josef Frank: in terms of Kaesz's furniture you can imagine numerous of the items in the portfolio of Haus & Garten, that furniture and interior shop and manufacturer and studio established by Frank and Oskar Wlach (and Walter Sobotka) in mid-1920s Vienna and which was a platform for their designs; while in many of Lukáts textile designs, certainly Napraforgó, but in many others, there is a comparison that can, must, be made to many of Frank's textiles, to Frank's approach to textiles.

Whereby we're not saying it's all the same, certainly Lukáts oeuvre is so varied and multifaceted that at times it goes in completely different directions, directions a Josef Frank didn't know existed, and even he had been aware of, wouldn't have explored; and similarly, we'd argue that whereas, for example, within Frank's oeuvre one does find a 1930s, possibly 1920s, bench subdivided into chairs, if a two seater rather than Kaesz's four seater and in a garden not at a dining table, and also finds a 1920s sideboard atopped by a vitrine, Kaesz's, and perhaps simplifying more than is prudent but which we feel necessary at this juncture... Kaesz's more systematic thinking, his furniture as tools for order, arguably, tends to lead his work in a different direction, generally, generalising; but there are comparisons that can, must, be made, not least in the position, atmosphere and character, the response they represent to the questions of the period in which they arose, the move forward that they knew had to be made, and the reflections mediated on that move forward's relationship with a past they argue mustn't be left behind in that move forward, needs to move forward with them.

Their demand for evolution not revolution.

And that not uninterestingly at a time of more or less ongoing revolution in the lands of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire.

And a comparison with Frank that is also, certainly in terms of Kaesz, in terms of Lukáts we're in no position to make any form of assessment, but in terms of Kaesz it is a comparison with Frank that is also a very clear influence of Frank. In Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat, Kaesz extols at great length over the 1920s and 30s 'Furniture School of Vienna' as personified by the likes of Frank, Wlach, Sobotka, Oscar Strnad, et al, a glowing admiration for 1920s and 30s Viennese furniture that reminds very much of that embodied in the 1969 exhibition Sitzen 69 at the, then, Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, that attempt to bring the spirit of Frank and the 1920s back to 1970s Vienna; and a 'Furniture School of Vienna' of which Kaesz exalts, for example, that it produced works which relied 'on the best English design tradition; its design is therefore easy, free and extremely inventive. Advanced tradition and modern spirit are united in these incomparably fine, elegant, deeply human pieces of furniture', it was furniture, for Kaesz, where, 'the requirements of today's times come into force: instead of luxury and individualism, the harmony of man with his surroundings. The requirement of expediency and simple beauty comes to the fore.', and was furniture developed by designers 'free from the temptations of currently fashionable "isms", but they also avoid an inappropriate degree of worship of tradition'.

Traits that, arguably, one can also follow through many, not all but certainly many, of Kaesz's works, if, as opined above, not a direct quotation of 1920s and 30 Vienna by Kaesz but a translation in context of both Kaesz's response to contemporary Hungary and to Kaesz's, and Lukáts', 'whims, thoughts and needs'.

Kaesz also, and not uninterestingly, noting that Haus & Garten's portfolio featured works by designers who 'respect tradition but are modern and witty'. Which, again, largely, not completely, by generally speaking, can, arguably, be claimed of those works by Kaesz on show in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960. Whereby we'd argue the greatest amount of wit on show in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 is without question to be found in Lukáts' graphics and patterns.

Which, yes, is and was quite a long diversion from Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, quite a long diversion from the subject at hand, but one we felt worthy of making: on the one hand by way of attempting to place the works on show in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 in context, or at least in that context, a context, a 1920s and 30s Vienna, in which viewing Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 we increasingly began to appreciate Kaesz and Lukáts oeuvres, or, again, primarily Kaesz's. And on the other because through exploring the influence of Josef Frank and his similarly inclined contemporaries in 1920s and 30s Vienna on the work of Kaesz and Lukáts, on the home of Kaesz and Lukáts, also allows you to better focus on two further contexts in which one can, should, must, view the work of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató: Functionalist, Constructivist, Modernism, as represented by the likes of their Magyar contemporaries Breuer Marcell and Moholy-Nagy László, or indeed Fischer József and Pécsi Eszter, and the late 19th/early 20th Szecesszió all were all born into.

Contexts which very real limitations of time and space prevent us from exploring here, sorry, we wish it weren't so, regrettably it is, but we'd very much encourage you do so on your own; save to note here that in Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat while Kaesz very much expresses an appreciation of the need for both Functionalism and Szecesszió as responses to prevailing realities, response to the questions of the period, was glad both moments arose, he was much more favourably inclined towards Szecesszió than Functionalism. Tends to diss Functionalism, and Constructivism, while embracing Szecesszió. And that with arguments and positions that are well worth reflecting on in more detail. But which we'll have to leave you all to undertake yourselves.

And to note here that as Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 allows one to appreciate, in the course of his career, or certainly in the earliest decades of Kaesz Homes' timelines, Kaesz moved from Szecesszió to a functionalist expression of Modernism, a functionalist definition of Modernism, distinct from that of Breuer, Moholy-Nagy, et al.

A move from Szecesszió that can be instantly appreciated in a comparison of the 1925 bedroom suite designed by Kaesz with all the other furniture in the house, even the 1928 console table met at the entrance, a work that is in the process of leaving the 1925 bedroom, is arguably having its first cup of coffee and washing its face; and specifically in a comparison of the voluminous, dominant, confident, 1925 sleigh bed with the abstracted, implied, confident, sleigh bed from 1940 in the room next door, a comparison that not only confirms the move made but the shift in positions and approaches that informed and enabled the move and how that move was enacted. A move that, arguably, the mid-1930s zebrawood sideboard indicates the tempo of. Indicates it was a gradual transition and not the sudden break with the past made by, for example, a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

And an arrival at a functionalist, functional, Modernism that can be appreciated not only in the aforementioned modular storage system, a system that could be straight from the Bauhaus Dessau workshops, or arguably more the Weimar workshop of an Erich Dieckmann, nor only in the 1940 (sleigh) bed, but also, for example, in the two sets of nesting tables, in the (we presume) aluminium bordered mirror, a work that alongside the desk and cabinet legs is the faintest of nods to the possible usefulness and acceptance of metal in furniture design, again reminding very much of a Kaare Klint in inter-War Copenhagen.

Or the lamp by Christian Dell for Gebr. Kaiser & Co that stands on Kaesz's desk; one of very few non-Kaesz/Lukáts designs to be found in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960. A metal lamp that indicates that Kaesz and Lukáts' vista went far beyond Budapest and the down the Danube to Vienna, that they very much existed in context of the wider European developments and positions of the period; and a metal lamp by a Bauhäusler who in comparison to the Moholy-Nagy László with whom he was co-responsible for the Bauhaus Weimar Metal Workshop, Moholy-Nagy as Formmeister, Dell as Werkmeister, didn't embrace the revolution of Moholy-Nagy, was much more in tune with the positions, the evolution, of a Klint or a Frank or a Kaesz. A Kaesz who clearly felt atuned to the positions and approaches of Dell.

And a move from Szecesszió that can also be followed in the work of Lukáts Kató, who, yes, we have somewhat rudely ignored these last few paragraphs. Apologies.

A Lukáts Kató whose use of folkloric in her earliest years, and as best represented in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 by the 1925 tapestry which hangs in the bedroom, can very much be understood in context of Kaesz's brief discussion in Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat on the use of folk art by Szecesszió creatives, his opinion that while some Hungarian creatives applied Hungarian folk art motifs to what he refers to as the 'basic form of Art Nouveau', by which we suspect he means a stylised, formalistic Art Nouveau, which we suspect he didn't approve of, other creatives employed Hungarian folk art as the basis for, as a means to, developing "új magyar formanyelv",'a new Hungarian formal language', that looking backwards for clues to ones identity that we all do, collectively and individually, in moments of upheaval and revolution. Which is important to remember in our contemporary age of upheaval and revolution and looking backwards. Forwards is always the better direction of travel, informed by the past, without repeating it.

An exploration of the folk art of the past by way of finding a way forward arguably embodied by Lukáts tapestry, and of which Kaesz probably did approve, naming as he does the likes of Kós Károly, Kozma Lajos and Lajta Béla as key protagonists of such an approach, and who were all important influences in his earliest, pre-1925, years. And in the 1925 bedroom suite.

A Lukáts Kató whose move away from Szecesszió, and from a desire to forge 'a new Hungarian formal language' based on folklore and the Hungary of the past, took her, as noted above, in varied and various directions, many of which can be found in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 including, for example, the aforementioned innocent, almost naively, so stylistic depictions of nature as represented by Napraforgó, a stylistic approach whose origins can very much be understood in the 1925 tapestry, is very much a development of her national romantic folkloric, but also creating much more realistic depictions of nature and also colourful, sprightly, playful, again almost naively so, illustrations of humans and animals and interaction, a reminder that a large part of Lukáts' oeuvre, a part not explored in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 but which you should explore, is and was as an illustrator of children's' books.

And a Lukáts Kató whose move from the folklore of traditional Hungary past to the shiny reality of modern Hungary present is perhaps best expressed via her commercial posters and her corporate/advertising graphic design work, an aspect of her oeuvre Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 offers but the briefest of glimpses to, if a glimpse that allows one too understand the move in Lukáts' positions and approach such represents and required.

Commercial work that is a further aspect of the cooperation between Lukáts and Kaesz: Lukáts and Kaesz often teaming up on commercial projects, on projects for commercial partners, Kaesz designing interiors and/or exhibition stands, Lukáts providing, for want of a better phrase, the graphic design, be that in terms of posters, catalogues, packaging, whatever. An aspect of their partnership that in addition to seeing them cooperate with local Hungarian companies also saw them work with numerous Viennese companies, Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 making particular mention of their work for and with the Vienna based chocolatier Altmann & Kühne for whom Lukáts designed packaging and Kaesz a shop interior, featuring curtains and murals by Lukáts; a shop interior designed in 1935 that while never realised, again we'll leave you to do the math yourself, was presented at the 1936 Triennale Milano.

A cooperation with Altmann & Kühne that helps underscore that the exchange between Vienna and Budapest, between Austria and Hungary in context of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató didn't flow like the Danube unidirectionally from Vienna to Budapest, it was a two-way dialogue, and a dialogue on numerous levels.

And an interior for Altmann & Kühne that featured two utterly charming metal chairs by Kaesz, two works of confection on which to sit, arguably the only two pieces of metal furniture in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960, works which in their charming manner pose the question as to why Kaesz didn't design more metal furniture, he clearly could; chairs which simultaneously remind of the 19th century Viennese metal wire furniture of a August Kitschelt and predict an Ernest Race's 1950s metal wire Antelope chair, that connecting of England and Austria in Hungary that can be followed elsewhere in Kaesz's oeuvre. And chairs, confections, which must be considered as a further example in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 of forward looking interpretations of historic models, a moving forward with the past that isn't in conflict with the past. A moving forward that questions the past, not by way of challenging it to justify its existence, but of trying to learn from it for the future.

Just as through enabling a questioning of the interiors and furniture of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 allows you to learn from their past.

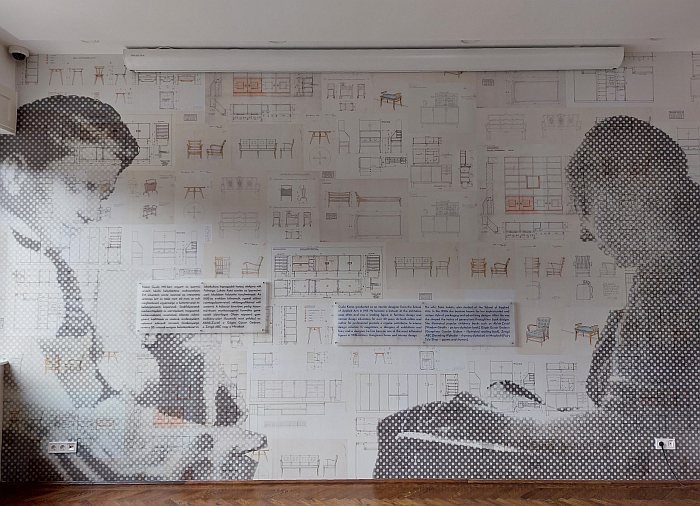

A compact bilingual Hungarian/English exhibtion that appears to grow the more you move through it, that expands beyond its physical confines the more you view and the more connections you make between that on show, Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 features in addition to various and varied projects and works by Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató photos of their work in situ, archive documents, draughts and plans, and an interactive station that invites you into the interiors of (near) all Kaesz and Lukáts apartments via contemporaneous photos.

And also invites you to visit their holiday home at Szentendre, to the north of Budapest, a house with views of the Danube designed by Kaesz in 1940; and a holiday home furnished with works that effortlessly reinforce and advance the considerations on Kaesz Gyula, Lukáts Kató, Josef Frank, Kaare Klint, Szecesszió, Functionalism, Modernism, et al initiated at and by Petófi ter 3. Including via a sofa by Kaesz that gaily plays with the function of upholstery; an armchair with a wickerwork seat and with armrests that exist more to help you lift yourself out of the chair than being places to rest your arms, a recurring, and thoroughly joyous, motif in Kaesz's armchairs, part of that wit in his designs; a gondola stool that is yearning for the Hungary of the Middle Ages while remaining resolutely in the Hungary of the mid-20th century; and a cabinet by Lukáts from 1940 decorated with a pattern, with flowers, leaves, fruits and birds, that stands somewhere between the 1925 tapestry and 1936 Napraforgó and which thus allows for deeper reflections on the nature of Lukáts move away from the folkloric expression of Szecesszió. And a work which, again, brings one back to Josef Frank. And also brings you to the Vanishing Cabinets of Hevesi Annabella, those contemporary Hungarian questions on and off the forms, symbolism, expressions and functions of Hungarian folk art, the links between the past and the future in our present.

An invitation to visit the homes of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató that for all the insights it allows, and themes it covers, can be but the briefest of introductions to Kaesz and Lukáts, is a tour through their homes that in every room leaves you with questions to follow up on your own, leaves you desirous to learn more, to 'get to know' Kaesz and Lukáts better, not least in context of those aspects outwith the scope of Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 including, for example, Lukáts aforementioned marketing design, Lukáts varied and various cooperations with Austrian clients, including the Wiener Werkstätte, or Kaesz's teaching, Kaesz's influence as a teacher and the contemporary relevance of that influence. Which, yes, brings one back to a Willy Guhl. And a Kaare Klint.

An invitation to visit the homes of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató that helps underscore the complexities of furniture (hi)story; helps underscore that for all the path of furniture (hi)story is often presented as a series of consecutive steps as neatly divided, delineated, as the dining chairs in Kaesz's dining bench, it isn't and wasn't, and that that path which is generally followed is one that has become established as the primary route via nothing more reliable than convention. And that following alternative routes not only allows you new perspectives, but can bring you out at a different location. That while European furniture from the first half of the 20th century where, 'the requirements of today's times come into force', furniture that is 'easy, free and extremely inventive', that represents an 'expediency and simple beauty' can be the steel tubing of the Functionalist Modernists, it can also be the wood of a Josef Frank, a Kaare Klint or a Kaesz Gyula. Much as Modernist American furniture from the second half of the 20th century can be from Charles and Ray Eames, but also from an Edward J Wormley. Or a folk art inspired and deeply rooted Alexander Girard, a creative whose various paths from folk art, arguably, find an echo in Lukáts, and who is also very present in Kaesz Homes 1925-1960.

Reminds that while novel materials and novel processes are without question one of the most important drivers of developments in furniture design and production, that isn't necessarily through their actual use but for all through the new perspectives and positions and possibilities they enable; but that you can realise novel positions, enable novel relationships, express novelties of society, in existing materials. That, as oft expressed in these dispatches, the (hi)story of furniture design isn’t successive but is aggregative, cumulative; Kaesz describes the (hi)story of furniture design as "egyes stílusirányzatok hosszú küzdelmét a megelőzővel", 'the long struggle of certain stylistic trends with the previous one', we'd obviously use the word 'positions' rather than 'stylistic trends', but otherwise broadly agree, if 'struggle' is understood in an intellectual not physical context, as argument and debate not a fight. That moving forward we noted above that questions the past, not by way of challenging it to justify its existence, but of trying to learn from it for the future.

And invitation to visit the homes of Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató that for all it is about Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató, is about helping Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató (re)take their place in the popular narrative of the development of creativity in Europe, helping Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató shake of the shroud of anonymity under which they currently labour, certainly outwith Hungary, is also an invitation to consider relationships between Budapest and Vienna in the decades immediately following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Budapest's disentangling from Viennese rule, relationships that after the 1939-45 War became disrupted by the placing of an Iron Curtain between Vienna and Budapest thus interrupting a well established and important dialogue between the two. A dialogue whose existence has become forgotten, Vienna standing in the popular narrative of the (hi)story of furniture design in discourse with a Munich, a Paris or a Brussels, but only rarely in discourse with a Budapest that over a long period of time was its most important collocutor. And is a dialogue that needs must be rediscovered to enable the writing of a more probable narrative of the (hi)story of furniture design in Europe.

And it is important that we do have that more probable narrative of the (hi)story of furniture design, for as a Kaesz Gyula reminds us, and as the homes of a Kaesz Gyula and a Lukáts Kató help elucidate, and as Home Sweet Home. The Archaeology of Domestic Life at SMAC – Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz, also recently elucidated, furniture (hi)story is not only 'a special branch of general art history and cultural history', but that branch that can bring us closer to the 'human environment and means of use' and to the 'living conditions, aspirations, and struggles' in generations past, and for all the role of human creativity and industry in the development of and response to such, than most other branches, than most other historical explorations, and as such furniture (hi)story is more instructive and informative in helping us chart a path forward than most other historical explorations.

If that is we can learn to read furniture (hi)story beyond the conventional narrative, without assigning any reduced work in wood to Scandinavians, without relying on 'isms' as crutches; if we can develop a more nuanced reading of furniture (hi)story based on the artefacts we have rather than placing the artefacts in our reading of (hi)story.

Kaesz Homes 1925-1960. The homes of designer couple Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató is scheduled to run at the Walter Rózsi Villa, 1071 Budapest, Bajza utca 10., until, we believe, April 2025. We're currently unable to locate a formal closing date, don't even know if as yet there is one, but generally Walter Rózsi Villa exhibitions run for a year and it opened in mid-May 2024.

Full information can be found at www.walterrozsivilla.hu

1Kaesz Gyula, Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat, Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest, 1969 The first edition of the book was released in 1962, we have a second edition from 1969. And are assuming the introductions are the same. Which they obviously might not be. Therefore the quote in the form it is given here, may not exist in the 1962 first edition, does exist as such in the 1969 second edition. But because we presume, recklessly, that it does, we say the quote is from 1962 not 1969. Apologies.

2For non-Hungarians, like us, Hungarian names can be, are, not the simplest of subjects to deal with, especially in context of married couples, and certainly in context of married couples in the years between 1925 and 1960, we therefore use the names the Walter Rózsi Villa use. And are assuming that the title Kaesz Homes 1925-1960 shouldn't properly be Kaesz/Lukáts Homes 1925-1960...... And because we're writing Kaesz Gyula and Lukáts Kató's names in the conventional Hungarian form, we do so for all Hungarians mentioned, or more accurately all born in the former Kingdom of Hungarian But not for non-Hungarians.

3and all subsequent quotes from Kaesz Gyula, Ismerjük Meg A Bútorstílusokat, Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest, 1969 As per FN 1 we have a second edition from 1969, the first edition was 1962.