As an (apparent) unending forest criss-crossed by visual axes and dotted with meadows, Park Sanssouci in Potsdam stands proxy for the garden design, the garden architecture, of 18th and 19th century Europe.

As an (apparent) unending forest criss-crossed by visual axes and dotted with meadows, Park Sanssouci in Potsdam stands proxy for the power and wealth and pomp and glory of 18th and 19th century Prussia.

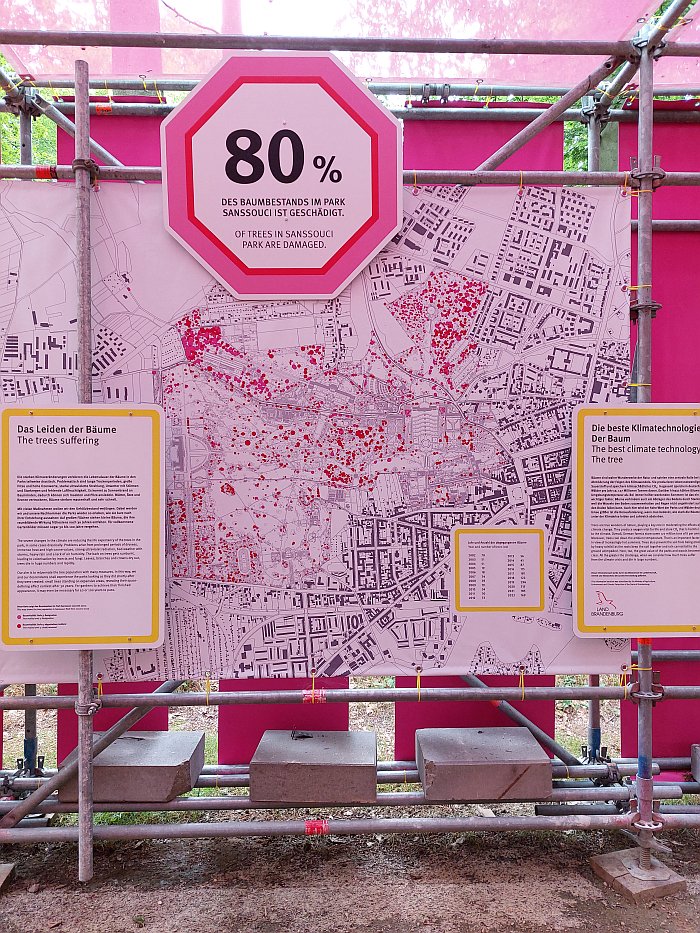

According to the Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, who today are responsible for maintaining and managing Park Sanssouci, some 80% of Park Sanssouci's trees are damaged, ill.

As an (apparent) unending forest criss-crossed by visual axes and dotted with meadows, Park Sanssouci in Potsdam stands proxy for the consequences and effects of climate change.

A reality employed in Re:Generation to, as the full title helpfully explains, discuss those effects – and the what we can do about it.......

Although the areal on which Park Sanssouci stands has a very long (hi)story, the (hi)story of the contemporary Park Sanssouci essentially begins in the mid-18th century with the construction of Schloss Sanssouci and its associated campus of buildings on the command of the, then, Prussian King, Friedrich II a.k.a. Friedrich der Große a.k.a. der Alte Fritz, a monarch still warmly remembered in the lands of the former Prussia for introducing the potato as a staple foodstuff. An act which adds Kartoffel Fritz to his many, many names. A Sanssouci Campus whose extension in the mid-19th century on the command of the, then, Prussian King, Friedrich Wilhelm IV a.k.a. Friedrich Wilhelm IV, was accompanied by the extension of, and remodelling, rephrasing, of the park and gardens by Peter Joseph Lenné, a garden architect whose use of Sichtachsen, visual axes, is the stuff of legend, certainly in the former Prussia, and a garden architect whose works dominate the popular image of the power and wealth and pomp and glory of 19th century Prussian nobility, the popular image of the power and wealth and pomp and glory of 19th century Prussia, just as much as the architecture of Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Ludwig Persius with whom he cooperated and with whom's buildings his gardens communicate.

And a park by Lenné that is largely maintained today as Lenné composed it; a great many of the trees that so define the park having been planted by Lenné, trees that having survived the demise of Prussia, the rise and fall of the DDR, and innumerable battles and Wars in the region over the centuries, are now threatened by the climate change that has been slowly growing in plain sight over those centuries.

But how does climate change affect trees? How does climate change affect large-scale landscaped parks and gardens? What can we learn therefrom? What can be done? What are the Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, SPSG, doing at Sanssouci? What can we all do? What can you do?

Such and similar questions are approached and discussed in Re:Generation in the course of a tour of 30 stations distributed across the park and divided into three thematic groups: Seeing the Signs which introduces the physical indicators of stressed and diseased and dying trees including, for example, dead seeds, bare crowns or explaining that trees can get sunburn, and that as with human sunburn it ain't good; Resource Water, a resource that on a warm summer's day can regularly be spotted shooting and whizzing out of a myriad spray heads into the innumerable thickets of Lenné's composition, and which is approached in Re:Generation in context of how it is supplied, how the trees access it, how it is used in Park Sanssouci, and how the authorities seek to reduce that use. The latter a subject to which we shall return in a couple of minutes. And Trees and Plants which presents some of the actions being undertaken at Sanssouci and elsewhere to better understand, diminish and counteract, the effects of climate change including, for example, making note of Cerambyx cerdo, the Great Capricorn Beetle, a park resident who in the question of if it is or isn't a pest offers some nice reflections on the way appreciations of the natural world, and our relationship with the natural world, change over time, aren't fixed in black and white but are transient in colour and also a park resident who helps elucidate the complexity of the myriad relationships necessary to the ongoing existence of such a park, and how climate change is impacting on those relationships; or the KERES research project undertaken by the SPSG in conjunction with academic partners in which future climate scenarios for Potsdam were developed, scenarios that predicted hotter drier summers and more, and fiercer, storms, scenarios whose consequences for the park are all too easy to grasp, scenarios whose consequences for the park were assessed and which now serve as the basis for producing plans of action.

Or the work of the Neue Baumuniversität, New Tree University, at Branitz near Cottbus: the Old Baumuniversität tracing its (hi)story back to Fürst Pückler that other noted 19th century garden architect, and 19th century ice cream designer, and an institution that was responsible for supplying the trees for Pückler's Branitz Park; the New Baumuniversität being Germany's largest model project exploring the preservation of historic parks and gardens in context of climate change, and also undertaking research to determine which tree species are best suited to thrive in the (expected) coming realities. Questions of which species are best suited to thrive in the (expected) coming climate realities explored elsewhere in Re:Generation, for all in context of the position that the answer may very well be trees native to other regions, that argument also made, for example, in Plant Fever. Towards a Phyto-centred design at Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden, that going forward plant migration may offer the best hope for our northern and central European parks and gardens, and that we should, as the Plant Fever Manifesto demands 'Stop the war on invasives'. Yes, metaphor. Re:Generation going, arguably further, and proposing actively inviting non-native trees; not necessarily the palm trees that stand so self-confidently, and knowingly, in front of the Orangerie, or at least not yet, that day may however come, but much more for example, discussing the possibility, the necessity, of replacing the sessile oak, Quercus petraea, that 'common' oak in north eastern Germany for the Hungarian oak, Quercus frainetto, a species better suited to hot, dry conditions. And which from afar looks very similar to the sessile oak.

A tour that very pleasingly forces you across the road to the Ruinberg, a part of Park Sanssouci most visitors never venture to, and thus a reminder that the park isn't just the grounds immediately bordering the various buildings, it is also the apparently wild and unkempt areas surrounding the central park, and also a reminder of the water tank atop the Ruinberg which since the days of der Alte Fritz has supplied water for the fountains, those other water resources that are so present and defining not just in Park Sanssouci but all similar historic parks and gardens. And also reminding of the wisdom of the past, something that is important in all contexts, including the building of water tanks that can catch rain water, but which is especially important in our dealings with the natural world, specifically in context of the tree nursery the SPSG plan to establish, if we've understood correctly, on the sides of the Ruinberg; a Sanssouci tree nursery akin to the Old Baumuniversität Fürst Pückler maintained at Branitz; a Sanssouci tree nursery that Lenné instigated in the 19th century before, one suspects, it was rationalised away as one can buy trees, one doesn't have to invest in nurturing your own; a 21st century re-instigation on account of the 'fact', certainly very strong evidence, that trees nurtured in a location are better adapted to that location, tend to thrive better under the local conditions, in comparison to those nurtured elsewhere and bought in. And a 21st century Sanssouci tree nursery that, having viewed Re:Generation, one strongly suspects will primarily propagate trees species not currently found in Park Sanssouci. Which reminds that a great many of the tree species 'native' to Sanssouci, as with the potato, aren't 'native', are migrants from centuries past. Yes, metaphor.

A tour that also takes you to the Potsdam University Botanic Garden, a location not technically part of Park Sanssouci but which all visitors to Park Sanssouci should visit, but most regrettably don't, and where one is introduced to a project undertaken jointly by the botanic gardens in Berlin, Halle, Jena, Leipzig and Potsdam in which citizen scientists record and document the effects of climate change in their own gardens, for all in context of the life cycles of plants, the floral calender, a project which aside from providing data for professional scientists also reminds that we are all in the same boat and that we are all needed to navigate that boat safely forwards. One of many such reminders that the changes we all need to make in our private gardens, our private spaces, are every bit as important as the changes institutions such as SPSG need to make in their public gardens, public spaces. Yes, again, metaphor. Parks and gardens are brilliant places for metaphors. Nothing thrives in a park or garden as well as a metaphor. Which may or may not be, as noted from Garden Futures. Designing with Nature at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, the reason that in (near) all monotheistic religions human life begins in a garden, in a garden paradise, before things go wrong. Much as Park Sanssouci was a garden paradise, a Lennélian paradise, before 80% of its tress were damaged, ill.

A tour that has no fixed route, you can visit the 30 stations in any order; thus a tour which for all Sanssouci is a park it is neigh on impossible to navigate the same way twice, so infinite are the possible ways through it, does provide a very pleasing alternative route, alternative routes, through the park. A route, routes, that although it/they take you to and past many of the buildings, causes you to ignore the buildings that are normally your focus, even the apparently unignorable Teehaus by Johann Gottfried Büring, and as such not only provides for an alternative perception of the park, but also reminds you that you're in a park, in a natural environment, a composed and managed and closely controlled natural environment, a human defined natural environment, that reality, as Julie d’Étanges states in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse in context of her carefully manicured wilderness garden, "Il est vrai, dit-elle, que la nature a tout fait, mais sous ma direction", 'It is true that nature has made everything, but under my direction." But a natural environment nonetheless. As confirmed in the person of Cerambyx cerdo.

But for all is a tour that the longer you are on it, the further you walk, the more your view on the trees and hedges and bushes becomes more acute, more focussed, more questioning, more active; despite the warm damp summer that 2024 has thus far been, and the abundance of lush green all around you, the further you walk the more you see that a lot of things aren't right, that for all the easy delight of the verdant vista from afar, in detail the problems are all too visible. You start to see the trees in the wood. And thus the more you walk the more you begin to appreciate not only the climate change on the natural World Heritage Site of the title, but also the what we can do about it, and that we must do something about it.

We collectively and individually.

In Potsdam and further afield.

As we were wandering through Re:Generation we overheard on a couple or so occasions Park Sanssouci visitors, judging from their accents we'll say locals rather than tourists, moaning about the presentation, complaining that the staging of the very loud and shouty pink, yellow, red, et al displays throughout the park had ruined the park, had defaced the park; comments which aside from missing the point that climate change is 'ruining', 'defacing' the park, and if those visitors want to keep the park as they imagine it should be they need to consider climate change as discussed on the loud and shouty pink, yellow, red, et al displays, albeit a climate change we suspect such individuals don't actually accept is an actual thing, is also to thoroughly miss the point that the whole point of the loud and shouty pink, yellow, red, et al displays is exactly to disrupt your viewing of the park.

Your physical viewing of the park and your conceptual viewing of the park. Your physical and conceptual viewing of the natural World Heritage Site of the title.

The displays disrupting as they do, or very regularly do, Peter Joseph Lenné's carefully considered and executed visual axes, which is very, very satisfying. And very, very important. Lenné had his reasons for the setting of the visual axes, not least to enable particular views, to frame particular impressions, highlight perspectives, define the importance of certain aspects; but unchanging visual axes tend to make us lazy in how we view things, we stop seeing, we become blind, we know what to expect and don't question that which we expect, we cease questioning that which is before us. Ever novel, ever unexpected, ever changing views are what is needed and what gardens, what life, should offer. And is what Re:Generation encourages.

The areal where the contemporary Park Sanssouci stands had a long (hi)story before it became Park Sanssouci, had a long (hi)story before the Hohenzollern established the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, as can be testimented by the oldest known tree in the park, an oak dating from ca. 1690, a period when the locals used the, predominately oak, forest for wood and to feed their pigs. Imagine how acorn foraging pigs would 'ruin' and 'deface' the park. Forests that in the early 18th century were harvested for wood for construction of the growing city of Potsdam, and thereby enabled the development on the newly won ground of the kitchen garden, pharmacy garden, Lustgarten, Pleasure Garden, et al that define 18th century gardens, enabled the start of the landscaping and formalising of the grounds, before with the construction of Schloss Sanssouci and the associated buildings der Alte Fritz initiated the establishment of Park Sanssouci, a park whose current form was, as noted above, defined by Peter Joseph Lenné. In the mid-19th century.

A mid-19th century Park Sanssouci has gotten stuck in. While the realities and contexts in which it exists have continually changed.

Time is frozen within the myriad buildings that form the Sanssouci Campus, that thing, as (more ore less) discussed in context of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar's 2023 Theme Year Wohnen, we do with historic houses once the context in which they once existed ceases, and which for all it negates an alternative use does allow for mediation of aspects of (hi)story and the path thus taken. A mediation that over time, certainly over more recent decades, has shifted from 'facts' and definitive descriptions of that path, those paths, taken, to being components of open-ended communal discussions.

But should time stop in a park. Should a park be frozen in time? Even a park in Prussia by Peter Joseph Lenné?

The areal on which the contemporary park stands previously changed with the times, previously changed with the realities and contexts in which it exists; yes, and also changed with fads and t*****, as noted from Of Gardens and People. Designed Nature, Art and Landscape Architecture at the Austrian National Library, Vienna, parks and gardens are, and always were, also about display and staging, are artificial spaces created for human users and human sensibilities and not for nature. Are "sous ma direction". Are not "sous la direction de la nature". Yet regardless of why it changed, the areal changed. Was always a response to the prevailing times. And now it is musealised, is artificially held in a form that once had a relevance and meaning but is increasingly becoming problematic.

Can one justify maintaining Park Sanssouci as Peter Joseph Lenné envisaged it, some 200 years after the fact?

Why?

Really?

We're not saying you can't we're asking why.

And why that why.

Thoughts on a freezing of space in time that has very obvious, and very informative, parallels with downtown Potsdam and the current determination, obsession, of the city authorities, and several extremely wealthy individuals, to rebuild downtown Potsdam as it was when the carriages of the Hohenzollern rolled though the streets rather than developing a forward looking Potsdam for contemporary society, a, if one so will. musealisation of downtown Potsdam; a focus on visuals as being correct rather than enabling a responsive space meaningful for contemporary realities, ¿a formalism rather than a realism?, ¿in park and city? that you can and should reflect on as you pass through downtown Potsdam on your way from the Sanssouci to the train station.

Thoughts on a freezing of space in time, and on the necessity, or otherwise, of any and every park and garden changing in response to prevailing realities that Re:Generation effortlessly allows you to undertake in a myriad ways, including, for example, the above noted greater suitability of trees from other regions in context of the coming climatic realities in Potsdam, the, arguably, near unavoidable reality of introducing (currently) non-native tree species into the park, of disrupting Lenné's selection, Lenné's composition. Which is a subtle change, but a change nonetheless. And one that, as noted above, will occur.

And thoughts particularly neatly enabled, and that in a much more tangible, direct, form, in context of Resource Water. A resource that is necessary for all organic life, but which is not only becoming rarer but whose behaviour is changing.

On the one hand changing rainfall patterns and intensities affect the level of the groundwater the trees rely on, for all the older trees often struggling to reach the lower groundwater levels that more regularly occur than they once did, necessitating the above noted spraying of the trees. And whereas the water for irrigating Park Sanssouci comes from the River Havel, and, as one can read in Re:Generation, has done since 1842, in context of climate change the amount of water that can be taken from the Havel, and the regularity with which it can be taken, are less than they were in 1842. Necessitating a new relationship with water, necessitating that reduction in water use we referred to above.

And necessitating the question if spraying old trees who can no longer reach the ground water is justified?

Why?

Really?

Then there's the question of the flower beds that twice a year are planted with annuals, and that, as one can read in Re:Generation, based on "historical models": then as private beds, today as public. Quite aside from destroying the health of the gardeners who have to contort themselves into all manner of improbable positions to plant then remove the annuals, and in-between regularly weed the beds to ensure everything is pristine, there is the water demand to prepare the seeds, propagate the plants and keep them blooming under the broiling summer sun. As one can read in Re:Generation, while standing next to pristine, weed free, beds of annuals, and next to gardeners ruining their bodies to maintain such, the SPSG grow some 38,000 annuals every year for Sanssouci, a component of some 500,0000 plants cultivated annually in Sanssouci for the various parks the SPSG maintain and manage in and around Potsdam and Babelsberg. But is that cultivation justified? Is that Resource Water use for annuals justified? Are beds of annuals based on "historical models" justified in context of prevailing climatic and aquatic realities?

Why?

Really?

Imagine the SPSG would announce in March, 'Sorry no annuals in the flower beds in Park Sanssouci this year'. There'd be chaos. Uproar. Consternation. The sort of person who complains about loud and shouty pink, yellow, red displays 'ruining' and 'defacing' the park probably won't notice the SPSG switching Quercus petraea for Quercus frainetto, but will notice a missing bed of annuals, and that, invariably, very vocally. As will a great many others. Globally. Social media would explode, the streets would be full of protestors, Potsdam's imminent demise would be predicated. Questions will be asked in parliament. Wealthy individuals will make their displeasure known. There may even be calls to give Park Sanssouci back to the Hohenzollern, who knew how to look after it, understood it, never 'ruined or 'defaced' it. And always had colourful beds of annuals.

But is that not the decision the SPSG must make? Is it not a decision that has to be made? Can the SPSG justify the Resource Water usage, and physical damage to gardeners, inherent in beds of annuals?

Can any city authority justify the Resource Water usage, and physical damage to gardeners, inherent in beds of annuals in its parks and urban spaces?

Can one justifying spraying old trees?

Can one justify maintaining Park Sanssouci as Peter Joseph Lenné envisaged it, some 200 years after the fact?

The tenor of Re:Generation, the language used, arguments advanced and positions taken by Re:Generation, tend to imply that, aside from a few tweeks here and there, the SPSG believe they can justify such; an objective, distanced, viewing of Re:Generation and of Park Sanssouci tends to imply they can't.

Tends to imply that as much as being an invitation for park visitors to reflect on the future of Park Sanssouci in context of climate change Re:Generation is also an invitation for the SPSG to reflect more honestly on the future of Park Sanssouci in context of climate change than they possibly have, and that possibly, arguably, on account of their institutional desire to maintain the park in its musealised 19th century form. On their perceived role and function as an institution of maintaining the park in its musealised 19th century form. Along with the interiors of the buildings.

Tends to imply that the SPSG need to free themselves from not just Lenné's visual axes, but their own institutional visual axes.

As we all need to free ourselves from Lenné's visual axes and our own private visual axes if we're to tackle not only the consequences and effects of climate change but try to stop, at least slow, climate change.

A varied and expansive bilingual German/English presentation whose facts and figures and discussion points effortlessly, entertainingly and unpreachingly explain the consequences of climate change on flora and fauna, park and garden, including elucidating several of the less popularly discussed and appreciated aspects, such as, for example, the negative effects of UV radiation on trees, or the fact that lots of rain doesn't automatically mean lots of water for trees, or also that climate change doesn't just directly damage trees but through setting them under stress makes them less resistant and therefore more susceptible to infections and infestations that they may otherwise have overcome, a fact previously noted in these dispatches, for example, in context of Alexander von Dombois's Beetlechair project and the reflections it enabled on how climate change is aiding and abetting the spread of the European spruce bark beetle and the Spruce Dieback it effects, or in context of the missing copper beech on the edge of the Lustgarten at Schloss Pillnitz, a copper beech that succumbed to a fungal infection it in all probability wouldn't have, had it not been stressed through climate change.

A presentation that quite aside from the thoughts on climate change in context of parks, gardens and Sanssouci it enables also allows for access to more general considerations and reflections on parks, gardens and Sanssouci.

Including, for example, allowing access to considerations and reflections on contemporary art and contemporary architecture. For centuries Park Sanssouci was about displaying art and architecture, was for centuries about art and architecture, relationships with art and architecture, the function of art and architecture: and for centuries Park Sanssouci has been the same sculptures, the same fountains, the same buildings. Why no contemporary art, or artistic objects that enable interaction and the developing of the ever novel, ever unexpected, ever changing views we all need? In terms of architecture there is contemporary architecture, met at Station 18 on the Re:Generation tour, a new building currently in construction for the park nursery, specifically a new multi-purpose building constructed in wood that will have a green roof and whose energy and heat supply has been designed to be low-impact; an ecologically and socially responsible building of the sustainable type we very much need today, a building that is very much of our time, and that stands diametrically juxtaposed to the selfish decadence and ostentation, or meaningless fashion, of many of the other buildings from other times. But a work that stands outwith the normal tourist routes through Park Sanssouci and which one suspects will slip into an anonymity once Re:Generation ends. But shouldn't it be part of the primary tourist route? Advertised and promoted as much as the buildings from, frozen in, the 18th and 19th century?

Why not?

Really?

Or allowing access to considerations and reflections on the function of parks, gardens and Sanssouci. When it was composed Sanssouci was, as with near all other similar parks and gardens, the private pleasure of a monarch, his family and allies. It is however more than a century since a Prussian monarch ruled over Potsdam, Park Sanssouci is a public space. One laid out and maintained for the private pleasure of the House of Hohenzollern. Which is in itself a problem, for, and as, for example, discussed from Of Gardens and People, as artificial approximations of the natural world, as a tightly controlled human space, parks need people in order to exist, the interaction with people makes any and every park meaningful and relevant. Be that the private interaction of a monarch or the public interaction of the masses. And while, yes, you can go walking and jogging in the park, and can cycle in a very, very, small part of it, most of the interaction is tourists looking at.

What is the function of Park Sanssouci?

Would it be so wrong to enable more proactive interaction? What would be so wrong with, for example, making part of the park available for community permaculture fruit and veg gardens? There used to be kitchen gardens at Sanssouci, why not today? Why does the use of Park Sanssouci start and end with Lenné? Why not with der Alte Fritz's Kartoffelbefehl, Potato Dictate? Why not foraging pigs? At least let the public tend the vines and figs on the terraces. Someone should. Must.

Thoughts on the function of parks, gardens and Sanssouci that lead one to the inescapable reality that going forward trees will be increasingly important in European urban spaces, that in context of ever warmer European urban spaces we will need ever more trees; trees that not only provide shade but whose presence helps reduce the ambient temperature. A dependence on trees that will mean not only the need for greater numbers of small scale urban parks in our dense European urban spaces, but that brings a new relevance to existing large scale semi-urban parks such as Sanssouci. A coming responsibility, a coming function, that needs to addressed now: in 30, 40, 50 years time we'll need a lot of healthy, thriving trees, not highly stressed 130, 240, 330 year old trees needing ever more water that have been retained simply because of associations with a previous age. Which isn't to say chop down all the old trees, isn't to advocate a programme of arboreal euthanasia, it isn't, is to focus on the need to use the available resources for the park we'll need in the future, not the one Lenné created in the past. And is to say, that at some point the SPSG will have to let park visitors sit on the grass, will have to let visitors shelter under the shade of a tree on a hot summer's day. Sorry! We appreciate proposing such is tantamount to blasphemy, and we don't want to offend anyone, but it must be said. Trees don't provide shade through being looked at from afar.

When Peter Joseph Lenné was planning and composing Park Sanssouci questions of climate didn't arise, questions of climate change and the consequences thereof weren't posed, couldn't be formulated, although they were being reflected on, or at least starting to be reflected on in the Prussia of that day: in 1844 Alexander von Humboldt, that famed Prussian naturalist, explorer, was acutely aware of the possible consequences of the changes "...humans produce on the surface of the continent by felling forests, by altering the distribution of waters and by developing large masses of steam and gas at the centres of industry", opining that "these changes are undoubtedly more important than is generally assumed..."1, and in doing so fairly accurately predicted the causes of our contemporary malaises. Predicted that they would be from human hand and brain and commerce. Even if he couldn't predict the level of their impact, the importance their impact would have. For that it was too early in the (hi)story of industrialisation. Thus for a Peter Joseph Lenné the focus wasn't, couldn't be, climatic considerations and the consequences of industrialisation, rather his focus was on the visuals, on the artistic.

A view, a perspective, a visual axis, that remains to this day.

Or put another way, there is a sign at the station The Life of Trees, one of the larger, more detailed stations, that states that "Gardens are living artworks", talk of "living artworks" echoed at the station Reaching for the 'Silver Axe', a station discussing the practice of removing healthy 'wild' saplings in order to ensure others have the light and nutrients they need, that thinning out of commercial forestry, that states, of the 'wild' saplings, "not all of them can remain in the artistic garden".

Is a garden 'art'?

It was in the 19th century when Lenné was creating Park Sanssouci. Architecture was also art in the 19th century. We now know different. The new nursery building may or may not be 'beautiful' but definitely isn't about art. And in the 19th century botanic gardens such as that run by Potsdam University were about systematics, classification, organisation, controlling, exploitation. We now know different. The Re:Generation station in the botanic garden is focussed on the environment in general, not the plant in detail. If architecture has changed why haven't parks and gardens? If botanic gardens have changed why haven't public parks and gardens?

Is a garden 'art'?

And if we stop thinking of gardens as 'art', does that enable us to approach them differently? Offer a different perspective?

Questions of perspective and a garden as an artistic composition that very naturally evoke a Lucius Burkhardt's question of Warum is Landschaft schön? Why is the landscape beautiful? Why is a park schön? Why is Park Sanssouci schön? As an expression of, as an act of, the from Burkhardt developed practice of Promenadologie, Strollology, Re:Generation is a wondrous invitation to reflect on a Burkhardt's argument that 'schön' exists alone in our in preconceptions, exists in that which we've learned externally, exists in strictly defined, unchanging, visual axes, exists in social media, and not in an active discourse with contemporary reality, and active discourse with 'beauty'. 'Schön' exists alone in that tourist gaze with which we all view the world outwith our daily borders. And has done since at least the 18th century. Loud and shouty pink, yellow, red, et al displays 'ruin' and 'deface' the 'beautiful' 'Park Sanssouci', the preconceived, learned, definitive, 'beauty' of 'Park Sanssouci' just as much as chemical works 'ruin' and 'deface' 'Switzerland', or a colliery tower 'ruins' and 'defaces' 'Schwarzwald', to name just two of the examples Burckhardt employs.

Can perceptions and appreciations of 'beautiful' change?

Have they not always changed?

Expect in context of landscapes, parks and gardens, where 'beautiful' is frozen in time.

Frozen in visual axes.

And colourful beds of annuals.

Thoughts on the function of Sanssouci, its freezing in a time long since past, and its 'beauty' that initiate thoughts and considerations on natural environments as a component of a particular identity, and the problems of associating a particular identity with a natural environment, and the even bigger problems of associating an identity with a controlled and managed natural environment, of associating identity with a natural environment "sous ma direction". Who is 'ma'? 'Moi'? Thoughts on identity that automatically lead into the associated thoughts on authenticity, on that particular human demand for things being 'authentic', be that in terms of food, music, dance or landscapes. Appreciations of authenticity, and for all of an 'authentic identity', that demand for the expression of an 'authentic identity' that are of great importance, and political and social relevance, in 21st century Europe; if 'authentic identities' that are invariably based on inventions, visual axes, 'sous ma directions' of the 19th century in which Park Sanssouci took on its current form. Or are based on the 18th century introduction of the non-native potato to the lands of Prussia.

Questions of unchanging parks, 'beauty', identity, authenticity, potatoes, et al that are also invitations to reflect on Sanssouci's UNESCO World Heritage status, and more generally on questions of Historic Site/Building Protection, questions of the potential harm of Historic Site/Building Protection, questions of what is being protected and why, questions that again a Lucius Burkhardt poses. If you change Park Sanssouci you lose your UNESCO World Heritage status, but Park Sanssouci, arguably, needs to change. Must change. Does UNESCO World Heritage status demand a formalist appreciation of and interaction with the world around us? Is UNESCO World Heritage status institutionalised Instagram? Is UNESCO World Heritage status a curse or a blessing? The SPSG's underscoring of Park Sanssouci's UNESCO World Heritage status in Re:Generation's full title tending to imply they see it as a blessing, and from a marketing perspective it probably is. Invariably is. Brings thousands of tourists every year. But tourism won't help us respond to the challenges of climate change. In many regards tourism helped bring us here. And marketing won't help us respond to the challenges of climate change. In many regards marketing helped bring us here. Had an Alexander von Humboldt been aware of marketing and its power to increase the, already large "masses of steam and gas at the centres of industry" he may have phrased his opinion differently in 1844. But he wasn't. So he didn't, couldn't. Can UNESCO World Heritage status help us out of our contemporary malaise? Really? Honestly? No, honestly......

Thoughts and questions that thereby also force one to question to whom do we owe the greater debt: generations past or generations future? Is not part of the responsibility of any and every generation to ensure that future generations don't have to endure the problems and horrors they themselves did? Is not part of the responsibility any and every generation to ensure a world in which war, dictators, hunger, et al are simply impossible. A responsibility previous generations arguably have't taken so seriously. Thanks! But which, if accepted as a position, allows Re:Generation to also be approached as Re:aliging generational responsibility and debt, as Re:sponsibility of Generations. At least in context of the damage we've done to the climate. In terms of war, dictators, hunger, et al it could take a few more generations before that responsibility is fully accepted. Assuming it ever is.

And in doing so and in being such and similar not only allows Re:Generation to use the natural World Heritage Site of its title as the basis for access to more nuanced reflections on our myriad and complex relationships with the natural world, nor only forcing us all to question why we expect and demand what we do from historic parks and gardens, to question what would happen if we all changed our demands and expectations of historic parks and gardens, but also allows Re:Generation to argue that garden design is a genuine design genre in that it emerged in the early 20th century from long established artistic and craft based practises in context of more focussed and urgent reflections and considerations on materials, relationships, function, form, societies, with cultural expressions and questions, with responses to prevailing realities and future challenges. Arose from artistic and craft based practises as society became increasingly complicated and novel positions became necessary, as existing positions ceased to provide solutions.

Allows Re:Generation to argue that contemporary gardens aren't art or commerce. But can be. Aren't decorative. But can be. But must always be design. Are only meaningful and relevant when they are design. Contemporary design. Peter Joseph Lenné was of his age. But that was that age. How would Peter Joseph Lenné design a garden in this age?

Allows Re:Generation to underscore that as an (apparent) unending forest criss-crossed by visual axes and dotted with meadows, Park Sanssouci in Potsdam stands proxy for questions of garden design, the garden architecture, of 21st century Europe.

As an (apparent) unending forest criss-crossed by visual axes and dotted with meadows, Park Sanssouci in Potsdam stands proxy for questions of the power and wealth and pomp and glory of 18th and 19th century Europe in 21st century Europe.

As an (apparent) unending forest criss-crossed by visual axes and dotted with meadows, Park Sanssouci in Potsdam stands proxy for appreciations that the answers to the question what we can all do about climate change of Re:Generation's title aren't just physical but require a conceptual questioning of spaces such as Park Sanssouci. Require a conceptual viewing of spaces such as Park Sanssouci as much as a physical viewing.

Require a conceptual viewing of any and every visual axis, as much as a physical viewing.

Re:Generation. Climate change in a natural World Heritage Site – and what we can do about it is scheduled to run at Park Sanssouci, Potsdam until Thursday October 31st, and is free for all. Whether you want to constructively view it or complain about it

Full information can bee found at www.spsg.de/regeneration, including the texts from the 30 stations, which is good, but not as good as viewing them in situ in Potsdam, not least because the photos, charts, tables etc are missing. And the direct context and examples. But is still good. Very good.

1Alexander von Humboldt, Central-Asien. Untersuchungen über die Gebirgsketten und die vergleichende Klimatologie. Zweiter Band (Dritter Theil), Verlag von Carl J. Klemann, Berlin, 1844 page 214