"The word 'document' which in the last few generations stood, and in many regards still stands for, papers relating to legal matters, such as deeds, contracts, affidavits and certificates, has in present-day professional usage reverted to its original meaning as derived from its Latin origin", opined Lucia Moholy in 1948, "and now applies to spoken, written, printed and other materials, produced and distributed for the purpose of imparting knowledge".1

With Lucia Moholy: Exposures Kunsthalle Praha allow one to approach a better understanding that for Lucia Moholy the most important "other material" of documentation was photography, and employs Lucia Moholy's photography, and her spoken, written and printed material, to enable an imparting of enhanced knowledge of Lucia Moholy and on the (hi)story of 20th century creativity.......

Born in Karlín, then a village to the north of Prague, today part of the northern 8th district of Prague, on January 18th 1894, Lucie Schulz enjoyed, by all accounts, a comfortable, secure, childhood in a well-to-do, Germanophone, middle class family. Accounts tending to be confirmed in the opening chapter of Lucia Moholy: Exposures which details Lucie Schultz's earliest years including presenting pages from some of her childhood diaries, as one learns she was an avid diary keeper most all her life, an avid documenter of her life, and also presenting some of the young Lucie Schultz's school certificates which tend to confirm that she was a very able and willing student. Certificates wherein one also can read that for her final exam at Prague's German Girls Lyceum in 1910 two of the oral subjects were The History of Hungary and the kulturelle Verhältnisse Ungarns, cultural relationships/conditions/realities of Hungary. Subjects that for all that they neatly link to Schulz's (still very) future marriage, also remind of the size of the, then, Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the varied and various peoples under its control. And one naturally wonders how the (hi)story of Hungary or Hungary's kulturelle Verhältnisse were told and taught in a late 19th/early 20th century Prague under Vienna's control. How they were documented in a late 19th/early 20th century Prague under Vienna's control. And how was the (hi)story of Bohemia documented in a late 19th/early 20th century Prague under Vienna's control.

From that Prague of the late 19th/early 20th century Exposures takes one on a largely chronological journey through the life and work, trials and tribulations, highs and lows of Lucie Schulz, of Lucia Moholy following her marriage to László Moholy-Nagy in 1921.2

A journey that includes stops in, for example, and amongst others, Weimar where Lucia and László moved in 1923 in context of László's appointment to the teaching staff at Bauhaus Weimar, and where, and as discussed from Lucia Moholy – The Image of Modernity at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, early dabblings in photography, and early considerations that photography could, possibly, be a medium to which she, potentially, was particularly well suited, developed - sorry! but we've got it out the way now, needn't return to it - developed into a profession, arguably a passion; a passion and a profession which, again arguably, was her primary creative occupation at first Bauhaus Weimar and subsequently at Bauhaus Dessau, be that in terms of photographing the works of students and the workshops, or in terms of photographing the buildings, for all those in Dessau, photos of buildings and works that, again as discussed from The Image of Modernity, for all that they are documentations of the buildings and works, and, certainly in terms of the works are today often the only version still in existence, the only surviving record, only documentation, they are also very much photographs that define and understand photography as more than just direct reproduction, as more than a still life or a landscape à la painting. Are photographs, or more accurately a great many of them are, photographs with an aesthetic language, with a composition, with an approach, very much in context of, and in dialogue with, the Neues Sehen, and the Neue Sachlichkeit, and the Constructivism, of the early 20th century, are photographs taken from a theoretical position as much as from a physical position.

Or in terms of her researching and developing more experimental approaches to photography, her pushing the boundaries of the photographic medium, process and materials in Weimar and Dessau, and that in close cooperation with, in an equal partnership with, László; something that can be perhaps best understood in their work on photograms, a long established camera-less photography technique Lucia and László advanced and re-framed - sorry! - in context of the positions of the 1920s. Photograms that today are a central element of László Moholy-Nagy's oeuvre and contribution to creativity. An element of László Moholy-Nagy's oeuvre and contribution alone. With only very rare mention of Lucia. Despite the close cooperation, equal partnership, in which the photograms arose.

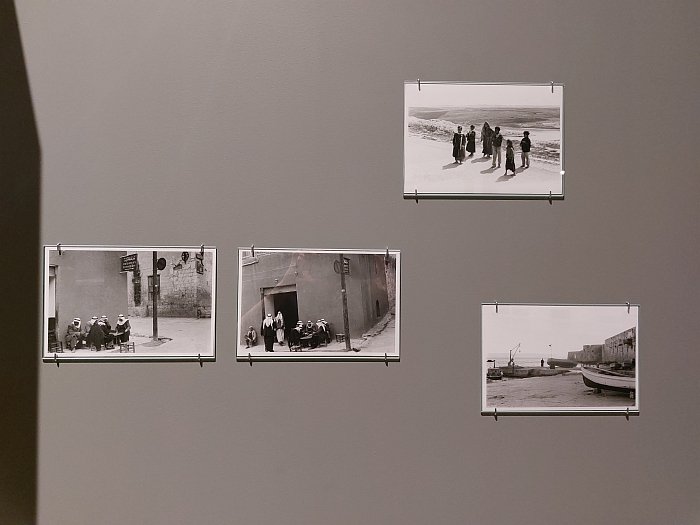

Or stopping in late 1920s/early 1930s Berlin where Moholy moved following her departure from Bauhaus and separation from László, a late 1920s/early 1930s Berlin where Moholy briefly taught at Johannes Itten's art college before, by Moholy's account, her enforced dismissal in 1933 at the behest of the Berlin authorities on account of her Jewish ancestry, a late 1920s/early 1930s Berlin where she became closely associated with many leading communists and socialists including, for example, Clara Zetkin or Theodor Neubauer, photographs and portraits of whom by Moholy can be viewed and studied in Exposures; an early 1930s Berlin from which Moholy travelled to Yugoslavia, a land, and its people, she explored, observed, approached, documented, as a photojournalist armed with typewriter, cameras and film, and that as an early protagonist of the still relatively young practice of objective photojournalism with its interest in the real life of real people, if one so will an alternative definition of the Neue Sachlichkeit, the Neues Sehen, a conceptual re-imagining of the Neue Sachlichkeit, the Neues Sehen, which had informed so much of her photography in Weimar and Dessau.

And an early 1930s Berlin from which Moholy was obliged to abruptly flee in August 1933 following the arrest of Neubauer, with whom Moholy at that stage was in a relationship; a flight from Berlin that took her to first Prague, then over Vienna, Zürich, Paris to London where Moholy, having been forced to leave all her glass negatives in Berlin, had to re-establish herself, a process that, as one learns in Exposures, was largely based around portrait photography, for all portraits of socialists and anti-fascists, yes you may be spotting a theme here, but also portraying numerous members of 1930s London's literary, artistic and academic elite. Who, yes, were often socialists and anti-fascists. And a London from where in 1939 Lucia Moholy published A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939, arguably one of the first writings of the (hi)story of photography to view it as more than a technical process or an artistic process, a work in which Moholy sought to give "thought not only to the achievements of photography as such, but the part it has played by mutual give and take throughout these hundred years in the life of man and society".3

Or as a quote from an undated preparatory note for A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939 emblazoned on a wall in Exposures states: "an art history of photography? no rather a cultural history".

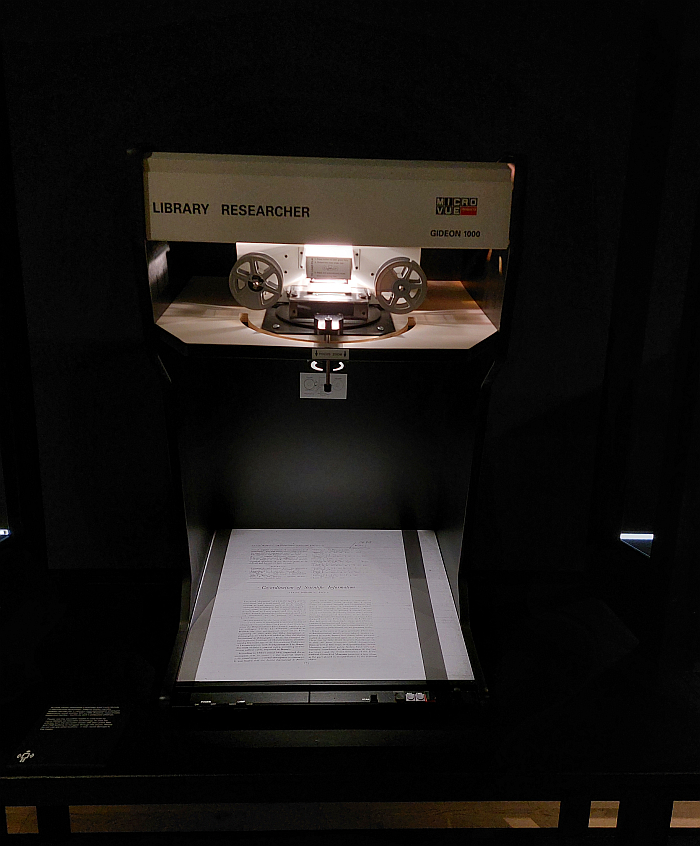

In 1947 Lucia Moholy acquired British citizenship and also established the company Documentary Services, a platform primarily concerned with microfilming, a form of photography, a form of documentation, that as with other forms of photography had arisen in the 19th century and which had taken on a new relevance as new technologies and processes and materials in the early 20th century enabled a wider, more affordable, utilisation; and a form of photography, a form of documentation, Moholy had added to her repertoire during the War years, and which over the subsequent post-War years saw her complete commissions for a variety of civic and cultural institutions, commissions that can very much be considered as a continuation of the "mutual give and take" between photography, man and society approached in A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939 beyond that 1939; commissions that included, for example, spending several years in the 1950s in Turkey as a UNESO expert working with cultural and education institutes, trips to Turkey that Moholy also used, as she used every travel opportunity, to tour the country, to study the culture, to meet the people, to take photographs, to document that which was around her. If photos from 1950s Turkey, documents of 1950s Turkey, that one learns a great many of which are currently unavailable on account of the ongoing, apparently endless, construction of the new Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin and the associated inaccessibility of its collection, and thus a reminder of the importance of institutions such as the Bauhaus-Archiv being accessible. A reminder that, as oft noted in these dispatches, historical objects on archive shelves are pointless and meaningless, utterly worthless, if they're not allowed to contribute to contemporary debates and discourses. Historical documents are worthless if they're not allowed, not enabled, to impart knowledge. How could, would, those inaccessible Turkey images expand the knowledge and appreciations imparted by Exposures? We all need the Bauhaus-Archiv open and functioning. It's been too long.

Moholy also serving as a microfilm consultant for the WHO on a project to establish a medical library in her native Prague, a commission that ended with the 1948 coup d'état and the establishment of a Communist government in the, then, Czechoslovakia. A 1948 coup d'état that as noted from Hej rup! The Czech Avant-Garde at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, also severely impeded the development and activities of the varied and various Czech avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, saw, essentially, the end of many of the pre-War Czech avant-garde movements; and a 1948 coup d'état that, again as discussed in Hej rup!, brought in the Communist government many of those Czech avant-gardists had long wanted, that many of those subjects of Lucia Moholy's portraits in Berlin and London had long wanted, albeit with consequences they hadn't imagined, consequences they couldn't imagine, weren't in the least happy with. And which naturally leads you to question what Lucia Moholy thought of developments in her native Prague? Exposures doesn't discuss that particular theme, but one suspects the answers can be found in her diaries. Will be documented in her diaries. And that they wont be opinions only related to the demise of the medical library project.

Having taken you from Karlín to London via Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Ankara, Nazareth, Paris, New York, Skopje, and a great many other locations, Exposures' journey through the life and work, trials and tribulations, highs and lows of Lucia Schulz/Moholy enters its final chapter in 1960 with Moholy's relocation to Zollikon on the banks of the Zürichsee, Switzerland, a country, as one learns, in which she enjoyed a more than deserved moment of re-discovery, re-recognition, re-acknowledgement.

And a Switzerland where Lucia Moholy died on May 17th 1989, aged just 95.

A journey that along its route discusses varied and various aspects of the life and work, trials and tribulations, highs and lows of Lucia Moholy, including, for example, allowing insights into the professional relationship with László, the two, as noted above, cooperating closely and extensively, for all in the Bauhaus Weimar years, in the research and development of more experimental approaches to, of pushing the boundaries of, photography, a closeness of cooperation that Exposures allows interesting, instructive, perspectives - sorry! - on; whereby, and as previously opined, Moholy's failure to formally record her contribution to projects undertaken with her much more visible male partner, her failure to properly document her contribution, a failure to document that exists somewhere between ironic and tragic given the rigour with which she otherwise documented, meaning much of that Weimar era work is today ascribed to László alone. In addition Exposures also helps underscore how Lucia's photographs documented and mediated projects by László, and thereby contributed to establishing and maintaining László's reputation, László's visibility, including, for example, Lucia's photos of László's stage and exhibition design work, or her reproductions of the joint photograms. A maintaining of László's visibility that has also contributed to her own (relative) invisibility. Which, again, lies somewhere between ironic and tragic. But which is also as informative as her photographs.

Or briefly, far too briefly, discussing Moholy's relationships with the Loheland and Schwarzerden schools, two female only education institutes established in context of the so-called Reform Movement of the early 20th century, an esoteric, proto-hippy, rhythmic gymnastic fixated, Reform Movement that also influenced and informed aspects of the earliest Weimar Bauhaus; Loheland and Schwarzerden schools that were also established in context of the female emancipation and gender equality movements of the early 20th century, movements that didn't really influence and inform Bauhaus Weimar or Dessau as institutions, if they did inform and influence many of the Bauhäusler. And Loheland and Schwarzerden schools that today are among the more unfairly popularly overlooked moments of the early 20th century European avant-garde, institutions which are necessary for the more complete appreciations of the early 20th century European avant-garde we all need, yet which are so often missing. Which is in itself highly informative.

Similarly all too unfairly popularly overlooked are the wives of the Bauhaus Meister, women such as Moholy who, as noted from The Image of Modernity, were expected to work for free for the famously cash-strapped Bauhauses, and that much to Moholy's ire; although she did acquiesce, for all taking the aforementioned photographs of the works of students and the workshops and photographs of the buildings, photographs which served a myriad functions for Bauhaus, but for which she was only very rarely credited, creatively or financially. Again much to her ire. A sense of unfairness at the gender realities at Bauhaus that caused Moholy to note "too much has been written about the Meister"4, and that more should, must, be written about the wives, a desire to write more about, to document more, the wives of the Meister which may or may not have been the motivation for the portraits of Nina Kandinsky and Anni Albers that are presented in Exposures alongside photographs of other female Bauhäusler and females in the wider Bauhaus circles including, for example, Edith Tschichold, Lily Hildebrandt or Otti Berger, the latter captured in a series of Dessau era photographs that we like to think document the spirit of Berger every bit as much as the body of Berger.

A sense of the unfairness of contemporary gender realities, an association with female emancipation and gender equality movements, a very real understanding and perception and acknowledgment of being a disadvantaged woman in advantaged man's world, an acute awareness of, and passionate resistance to, a long-established patriarchal society that refuses to yield, that is particularly tangible in a letter on display in Exposures written in 1955 to Johannes Itten in which she thanks him for his reference in context of an application for a Professor of Photography position at an unnamed institution, an application in which Moholy reached the final round "aber wie so oft hat schliesslich eben doch ein Mann den Posten bekommen", 'but, as so oft, ultimately a man did get the job'. A "man" who also got the job when, for reasons unknown, that first "man" didn't take up the post and the Professorship was re-advertised. "Das Prinzip der gleichen Rechte hat sich doch noch nicht überall durchgesetzt", Moholy laments to Itten, 'the principle of equal rights has not yet established itself everywhere'.

A sentence written in 1955 that, and as with so much of Lucia Moholy's work, has lost nothing in contemporaneousness over the decades.

And a journey through the life and work, trials and tribulations, highs and lows of Lucia Moholy that at 2 of its 14 stations discusses the fate of the photos Moholy took at Bauhauses Weimar and Dessau, or more accurately, the fate of the glass negatives from Weimar and Dessau; a percentage of the total that tends to underscore the relevance, the centrality, of the 'lost' glass negatives in the biography of Lucia Moholy, in the life and work, trials and tribulations, highs and lows of Lucia Moholy.

As previously discussed from The Image of Modernity, in context of her rapid, and enforced, flight from Berlin in 1933, Moholy left her glass negatives with László; the glass negatives being as they were too heavy and too fragile to carry at short notice on such a rapid, unpredictable, unplannable flight across a turbulent Europe.

Post-War Moholy became aware that a lot of photographs printed from her glass negatives were being published in articles and books and exhibitions concerning Bauhaus and Bauhäusler; were being printed from glass negatives she alone possessed the rights to but whose whereabouts she had no information. Eventually, and cutting a very long, and very informative, story very short5, it transpired that Walter Gropius, despite repeated claims he didn't have the negatives, had the negatives. Or at least a great many, and considered them his property. Or perhaps more charitably, considered them Bauhaus property, the property of the legacy of Bauhaus that he was responsible for maintaining. And so Gropius let them be used without any mention of Lucia Moholy as the photographer. An act that contributed greatly to Moholy's slipping into a relative anonymity, not least in context of her contribution to Bauhaus Weimar and Dessau, her contribution to the development of creativity in the 1920s and 30s, to the development of photography in the 1920s and 30s, to the (hi)story of photography, her very real contribution to not only A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939 but to (the still to be penned) Another Hundred Years of Photography 1939-2039, and thus the necessity of her re-discovery, re-recognition, re-acknowledgement in post-War Switzerland.

A necessity of her re-discovery, re-recognition, re-acknowledgement Exposures tends to re-inforce re-mains acute and urgent to this day.

A chapter of Lucia Moholy's biography, a central moment in the development of Lucia Moholy's biography, that is particularly well illuminated in Exposures - sorry! - not only through the featured newspaper and magazine articles, and television interviews, from her time in Switzerland that help underscore the degree to which she had slipped under the popular radar, the amount of her biography that had to be retold before she could be allowed to contribute to discussions on a path of creative (hi)story she had helped lay, but also through the presentation of an exchange of letters with Sigfried Giedion discussing the use of her photos in an unnamed book, but which we suspect, presume, is and was Giedion's 1954 Walter Gropius. Mensch und Werk, a work that takes an uncritical, lightly hagiographic, approach to its subjects, and which contains numerous uncredited Moholy photos, and numerous uncredited photos by other photographers who clearly were familiar with Moholy's 1920s and 30s work; and a letter in which Moholy not only berates Giedion for allowing her photos to be used uncredited, and unremunerated, when he knew fine well whose photos they were, but highlights graphically and unequivocally the problems caused by the lack of income, and lack of acknowledgement, from and of her photos, her work, and also the unspeakable unfairness of the situation. And a forcefulness of berating that tends to confirm the impression generally given by Exposures - sorry! - of a very self-confident individual who was more than capable, and perfectly happy, to look after herself.

And for all is illuminated and highlighted through a 1954 letter to Moholy from Walter Gropius in response to Moholy's repeated questions about the negatives; a letter in which Gropius celebrates himself in the opening paragraph, before attempting a spot of casual gaslighting and subsequently and very self-evidently taking from Lucia Moholy any and every claim to the negatives. The rat. The utter rat.

Moholy did, eventually, get her negatives back, her determination and will being stronger than Gropius's, and she was always going to see through the gaslighting; or at least got some 230 of them back, ca. 330 from the ca. 560 left in Berlin are still missing. And much as you really, really, want that to be Gropius's fault, it probably isn't, is probably a simple fact of War, of the NSDAP enforced emigration of László and/or Gropius, or, hopefully, simply one of incorrect post-War archiving; however, by the time Lucia Moholy got her glass negatives back the damage to appreciations of her contribution to Bauhaus Weimar and Bauhaus Dessau, and the damage to her visibility on the helix of creative (hi)story, had been done.

Exposures not only allows you to better understand why that is and was negative - sorry! - for Lucia Moholy, but why it is and was negative for us all through the skewing of the narrative of European creative (hi)story it gave rise to, and still perpetuates.

But Exposures also, and most engagingly so, does that thing exposures do, performs that function of exposures: allows a negative to develop into a positive. Allows a negative to become a meaningful representation.

Enables documents to impart knowledge.

Including knowledge beyond that they were originally produced and distributed to impart.

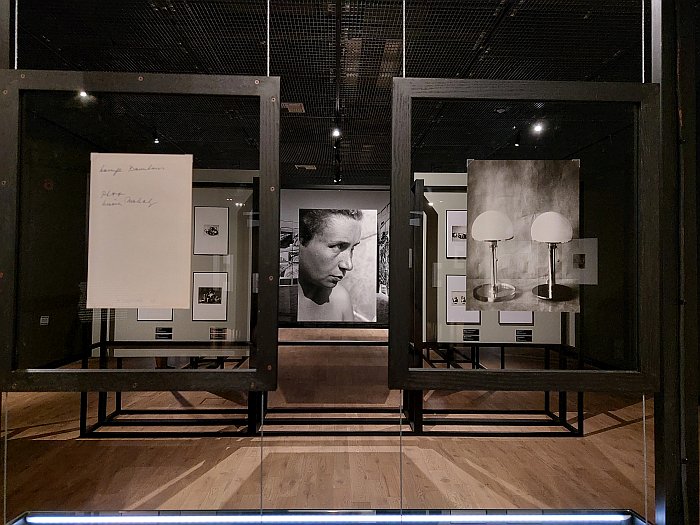

A well paced and easily accessible bilingual Czech/English presentation that features a couple of very satisfying exhibition design moments including, for example, presenting Moholy's writings on microfilm on microfilm, thereby making a technology ever fewer are familiar with tangible, and also featuring a number of interventions by Chicago based, Prague born, artist Jan Tichy that, primarily, concern themselves with Moholy's lost, found and missing negatives, Exposures is, somewhat obviously, primarily based around photographs, that most defining element of Moholy's oeuvre; photographs from across all periods of Moholy's long career and the various and varied genres in which she photographed in the course of that long career. But also moves beyond the photographs to discuss, for example, her teaching, a role that she never formally possessed at the Bauhauses but which she performed not just at Itten's Berlin school but at a variety of institutions in and around London during her years in England, or her writing, be that the books and articles she published, public lectures she held and radio programmes she broadcast, or the many books she planned yet for various reason never realised, but whose unpublished material is still very informative.

And writings that remind us all that before she discovered her passion for, and proficiency in, photography, Lucia Schulz/Moholy was primarily active in publishing and editing. And that she was, certainly initially, responsible for editing and managing the publication of the Bauhausbücher. Was responsible for preparing and disseminating the Bauhaus documentation. The question as to the authorship of the great many uncredited photos in, certainly the Bauhausbücher before Moholy left Dessau for Berlin, but arguably also several after that, is one we'll leave you to pose.6

But primarily Exposures is photographs.

Photographs that while they include a great many regularly seen Lucia Moholy works, also include a great many lesser known works including, for example, Moholy's portrait of one Madam Palmer, a cleaning lady in London, so not part of the Smart Set Moholy also photographed in London, but a photo taken with the same technical approach, same personal approach, the same intimacy, the same trust, same theoretical perspective, as those of the Smart Set and which as such is a portrait that not only enables differentiated considerations on 1930s working class London, but a questioning of what are the differences between the Smart Set and the Cleaning Lady Set? And who defines them? Why?

Or five photos of Denham film studios on the north-western edge of London, a complex designed in the mid 1930s by Gropius and Maxwell Fry, five photos that remind us all, document, that International Modernism did come to the UK and in the person of Maxwell Fry moved from the UK to, for example, India, reminds that Gropius was active in the UK before moving on to America, questions if Gropius already had the Bauhaus glass negatives while commissioning Moholy to photograph Denham. The absence of photos of Denham in Giedion's Walter Gropius. Mensch und Werk strongly implying Gropius didn't have those negatives.7 Which must have annoyed him. The rat.

And five photos which allow for a direct comparison with Moholy's well known photos of Gropius's Dessau atelier building, and to question why the very obvious differences, is it just differences in the reproductions of Denham for Exposures as opposed to Moholy's Dessau originals, technical differences, or something more conceptual, positional, emotional? Is it the mood of the Denham photos that irritates and confuses? Is there perhaps a distance to Denham that didn't exist in Dessau? Was Moholy perhaps more involved with the Dessau atelier building than the Denham film studio? And if there is, and if she was, what can we all learn from that?

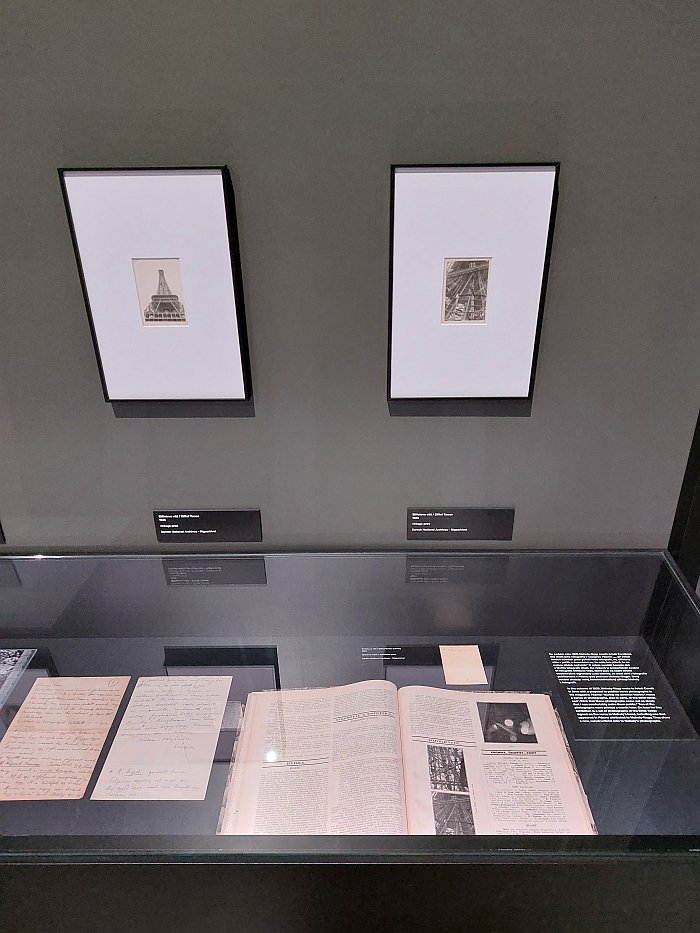

Or a trio of photos by Moholy of the Eiffel Tower taken during Lucia and László's visit to the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, three works which present a near textbook Constructivist viewing of the Eiffel Tower, a viewing that utterly ignores the engineering and innovation, and the symbolism, to explore the Eiffel Tower as lines, forms, relationships, light, shadow et al. A trio of photos one of which was published in the Czech magazine Pásmo, a magazine published by the Brno section of Devětsil, that so defining Czech avant-garde grouping of the 1920s, and which thus reminds of how networked the 1920s European avant-garde were in a period when Europe was still adjusting to the new post-Empire realities; albeit a photo by Lucia that was published attributed to László. A misappropriation no-one seems to have tried to correct, and which tends to underscore that the misappropriation and lack of credit and acknowledgment afforded Lucia Moholy has a very long tradition. And a lot of male causes. Including males who did nothing about rectifying the situation.8 See also a Mies van der Rohe not standing up for Lilly Reich at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, an Alvar Aalto not standing up for Aino Aalto at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, or a Charles Eames not standing up for Ray Eames at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. And yes we can get in a László Moholy-Nagy not standing up for a Lucia Moholy at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. But will do so in a footnote.9

Photographs that not only help explain how Lucia Moholy photographed, how Lucia Moholy understood photography but also allow one to better frame - sorry! - questions of why Lucia Moholy photographed, why she swapped literary and publishing practice for photographic practice. Exposures tending to imply that the subject in itself wasn't the focus - sorry! - of her photography; tending to imply that whether it was the lines, forms, relationships, light, shadow et al of the Eiffel Tower, works from Vorkurs at Bauhaus Weimar, the atelier building at Bauhaus Dessau, 1930s British literati, the streets of Nazareth, Turkish cultural artefacts, or whatever, it was all one and the same to Moholy. Thus tending to imply that Moholy's interest lay elsewhere.

"The tools generally used in the arts since centuries, such as pencil, chalk, brush, chisel etc, carry out what the hand wants to do", Moholy notes in A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939, continuing that the hand, in turn, does that which the brain wants and that the question whether or not is art "depends mainly on the mind, partly on the hand, and to a negligible degree only on the tool".10 With contemporary "mechanical" tools, such as a camera, according to Moholy, that changes "the tool's share grows more important, while the hand's share is reduced to a minimum. The mind's share, on which the result mainly depends, upholds its position as the primum mobile. The result may be a work of art - or may not"11.

With her own photography, one can argue, Exposures allows one to begin to develop an argument, Lucia Moholy was on the one hand embracing the possibilities of new technology for new humans and for new society that was at the core of much of the early 20th century avant-garde, was replacing the unreliable hand with the precise machine, that out with the old in with the new of the age, and was also undertaking the contemporary challenging of the primacy of art in the realisation of, appreciations of, and for all relationships with the products of contemporary society, an art that for centuries had, arguably, enjoyed an unchallenged primacy not only in decorative goods but in utilitarian goods, and also in architecture, an art that photography, not least on account of its mechanical basis, could be but needn't be, a decorative that photography could be but needn't be; but a photography which, one gets the impression - sorry! - viewing Exposures that for Moholy was, had to be, utilitarian and meaningful. The products of photography as functional goods. An idea that can also be approached in László and Lucia's 1922 article Production-Reproduction in which they opine, "we must strive to extend the apparatus (means) previously used only for reproductive purposes to productive purposes as well"12, must strive to make passive instruments active.

And thus allows one to begin to argue, certainly having viewed Exposures causes us to begin to argue, that for Lucia Moholy the primum mobile was the question of why an image was captured on a glass plate or a photographic film, the function of the image, and how an image was captured on a glass plate or a photographic film, the technical process be that artistic or scientific, rather than (directly) the subject of the image. The subject was not unimportant, but wasn't decisive. And which, again arguably, put her at odds with many of her 1920s and 30s contemporaries, including many of those whose works and buildings she photographed, who in their desire for standardised, optimised goods were very much focussed on the subject, contemporaries for whom the why and how weren't unimportant, but the what was always at the forefront. There is however no standardisation or optimisation in Moholy's works, often an efficiency, but rarely more. And invariably a function. And which makes the step from photogram and Neues Sehen to microfilm much easier, more direct, less confuse.

A position which if accepted, and you don't have to, but if you do, allows a Lucia Moholy to contribute to the very urgent discussions on our A.I. future, discussions on our contemporary out with the old in with the new in all spheres of existence, including the creative, and the question of photography without a camera that Lucia and László had approached in their Weimar photograms and which we can all undertake today in the comfort of our own phones thanks to A.I., that question of the function of photography in our A.I. future, the relationships between art and photography in our A.I. future. And which will be an important chapter of Another Hundred Years of Photography 1939-2039. Or The Final Hundred Years of Photography 1939-2039 as it's title may very well be once it is penned.

And also allows one to approach an appreciation that for Lucia Moholy photography was always a question of documenting, regardless of the context in which a photo was taken, regardless of either the theoretical or physical perspective from which it was taken; a photograph was always something produced and distributed for the purpose of imparting knowledge.

And "the result may be a work of art - or may not".

That is in any case always a question for the viewer.

Or perhaps better put, became in the course of the early 20th century increasingly a question for the viewer, ceased to be a question answered in the mind of the creator of a work and became one formulated in the mind of the viewer.

And photographs that also help underscore the degree to which Lucia Moholy defines the popular viewing of Bauhaus, and confirms the degree it has done since the 1920s: Moholy's photos were one of the primary documents during the years of the Bauhauses existences, and were, have been, one of the primary documents in the decades since Berlin's closure in 1933. Have been one of the primary imparters of knowledge on and off the Bauhauses. A Hundred Years of Bauhaus As Photographed by Lucia Moholy 1923-2023 (and beyond).

Are photographs that help underscore the degree to which Lucia Moholy defines the popular physical viewing of not just the Dessau atelier building and Meisterhauser but also of the popularly known products of the Dessau and Weimar workshops, the latter being testified to in Exposures by numerous of Moholy's photographs of, for example, Wagenfeld & Jucker's lamp, or Marianne Brandt's ashtrays, or Erich Dieckmann's furniture or Marcel Breuer's furniture, the latter also being visible in many of Moholy's photos of interiors which help underscore the degree to which Moholy defines the popular viewing of Bauhaus interiors, defines a primacy of steel-tubing in Bauhaus interiors that may or may not have existed.

And also help underscore the degree to which Lucia Moholy defines the popular conceptual viewing of Bauhaus, not alone there are and were a lot of protagonists in developing the idea of what Bauhaus is and was through photography, a Herbert Bayer, a Marianne Brandt, a Hajo Rose or a Walter Peterhans spring most instantly to mind, and of course László, lest we forget Bauhaus existed in an exciting era for photography; but viewing Exposures is to begin to better appreciate that how the Bauhauses are popularly conceived and understood as intangible concepts more than tangible institutions, buildings and objects is largely mediated though photographs, through visuals. Allows one to better appreciate that way we associate the manner of a photograph for the subject being photographed, transpose the theoretical position of the photographer onto the physical subject. Underscores the important role of Lucia Moholy's photographs in the establishment of that transposition. And also allows one to better appreciate the dangers therein.

On the one hand cameras can't lie but they can struggle with truth, are, as a Moholy underscores, tools of the photographer, and photographs are always realised in context of the photographer, the photographer's theoretical position, the photographer's brain being primum mobile, are rarely independent. An objective lens can also be subjective. Moholy's photos of the Dessau atelier building are documents of the Dessau atelier building taken from a theoretical as well as from a physical position, a physical position, physical positions, that the Dessau atelier building is still, invariably, photographed from be that by tourists or professionals, our physical gaze on Bauhaus Dessau has barely changed since the 1920s, and a theoretical position, a Constructivist, position Bauhaus Dessau is also invariably viewed from, and equally invariably only viewed from. Certainly primarily viewed from. In addition the Neue Sehen of Bauhaus and Weimar was often, invariably, staged, certainly planned and rehearsed and deliberate, unlike the spontaneous, in the moment, Neues Sehen Moholy practised in, for example, Turkey or, the then, Mandatory Palestine. Which is important to remember. Not least in context of steel tube furniture.

And on the other hand not all Moholy's Bauhaus photographs are textbook examples of Neues Sehen or Neue Sachlichkeit or Constructivism. A great many are. But some are quite poor. Some are quite dull. Sometimes Moholy is clearly struggling with the light in glass fronted International Modernist buildings, much as the users of glass fronted International Modernist buildings often struggle with the sun, or the lack of privacy or the lack of insulation. Physical, tangible, problems of glass fronted International Modernist buildings that are often missed, ignored, in the intangible plays of lines, forms, relationships, light, shadow et al in which context they are generally viewed in the Neues Sehen, Constructivist, photographs which dominate our appreciations of the Bauhauses. And in any case, the Bauhauses weren't only Neues Sehen, Constructivism, Functionalism et al. Regardless of what the popular Bauhaus narrative, and the popularly known Bauhaus photos, tells us. Nor were the Bauhauses always fun. Regardless of what the popular Bauhaus narrative, and the popularly known Bauhaus photos, tells us. And not everything produced at the Bauhauses was good. Regardless of what the popular Bauhaus narrative, and the popularly known Bauhaus photos, tells us. Nor were the Bauhauses only a force for good; as Bauhaus and National Socialism at Klassik Stiftung Weimar, or Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, help elucidate, document, it was also a force for evil. Or, more accurately, individual Bauhäusler were forces for evil. Much as individual Bauhäusler were unquestionably forces for good.

Thoughts which underscore why it's always important to always view a full scene not just the photographers conceptual and physical perspective on an aspect of that scene, and that acquiring that full scene necessitates having as many documents as possible.

Be that scene a school, a city, a country, the (hi)story of art, the (hi)story of architecture, the (hi)story of design, the (hi)story of the Bauhases, the (hi)story of photography, the 'History of Hungary', or the biography, the life and work, trials and tribulations, highs and lows of a creative.

Until very recently much of the documentation of Lucia Moholy was unknown, as was the fact that much of the documentation of Bauhaus Weimar and Bauhaus Dessau was by Lucia Moholy, meaning we were all denied a full viewing of Lucia Moholy. Had but limited perspectives on and of Lucia Moholy. Limited perspectives partially hidden by the shadow of László Moholy-Nagy.

Through the wide variety of photographs and photographic approaches it presents, through the wide perspective - sorry! - it offers on Lucia Moholy's photography, through the opportunity it allows to approach Moholy's Bauhaus photography in context of Moholy and not in context of Bauhaus, through the opportunity it allows to approach Moholy's Bauhaus photography in context of Moholy's wider photography, including her apparently unrelated microfilms, through the manner in which it neatly allows for an alternative take - sorry! - on Lucia Moholy as a photographer, through helping one better place Lucia Moholy in the (hi)story of photography 1839-2039, through the manner it expands the Lucia Moholy biography beyonds the Bauhauses she is is most commonly associated with, the way it makes clear Weimar and Dessau were but brief stops on a long journey, through the insights it offers as to how Lucia Moholy can contribute to expanding, and correcting, the established narrative of creativity in 20th century Europe, through the manner in which it enables you to study the documents by Lucia Moholy together with, and in context of, the documents of Lucia Moholy, Exposures is an important moment in enabling that more complete viewing of Lucia Moholy to develop. A more complete viewing that is necessary not only in context of allowing Lucia Moholy to retake her place on the helix of creative (hi)story, but also in context of enabling a more probable reading of the documents of 20th century creativity in Europe and thereby of the writing of the more probable narrative of creative (hi)story in Europe we all need.

For documents can only impart knowledge if we are exposed to them.

Lucia Moholy: Exposures is scheduled to run at Kunsthalle Praha, Klárov 5, 118 00, Prague 1 until Monday October 28th.

Full details can be found at www.kunsthallepraha.org

1Lucia Moholy, Co-ordination of Scientific Information, Research1, No 4. January 1948, page 1 (we hope the reference is correct, we've only seen in Exposures, have been unable to locate it.)

2László Moholy-Nagy was born László Weisz, changed his name to László Nagy as a consequences of the family's abandonment by the father and his subsequent raising under the guardianship of his uncle, Gusztáv Nagy. And later added Moholy, the name of the town in which Gusztáv Nagy lived, the contemporary Mol, Serbia, and that, as far as we understand, because he believed double barrelled names sound better. Much as Ludwig Mies added 'van der Rohe' to sound Dutch. Lucie Schulz, as best we can ascertain, was always just Lucia Moholy, i.e. took on that part of László's invented identity that had no direct relationship to his birth name, or the names of his family, rather was that part László had added by way of illusion, that part of László's identity he had actively sought out, actively formed. Which may or may not be art, may or may not be feminist, but is definitely interesting. When Lucie became Lucia, we no know. Nor if it was deliberate or an administrative error. On her 1910 school certificate she is however Lucie, thus we use Lucie for her childhood in Prague and Lucia for everything that came after. But that may not be exactly how it was.

3Lucia Moholy, A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939, Bauhäusler. Dokumente aus dem Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Band 4, Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, 2016 page 14

4Lucia Moholy, Frau des 20. Jahrhunderts, unpublished text in Bauhaus Archiv Berlin, quoted in Mercedes Valdivieso, Lucia und László Moholy-Nagy Ein "symbiotische Arbeitsgemeinschaft", in Renate Berger [Ed] Liebe Macht Kunst. Künstlerpaare in 20. Jahrhundert, Böhlau Verlag, 2000, page 71

5One of the first and fullest tellings of the tale is: Robin Schuldenfrei, Images in Exile: Lucia Moholy’s Bauhaus Negatives and the Construction of the Bauhaus Legacy, History of Photography, Vol. 37, Nr. 2, May 2013

6Not uninterestingly, in 1930 Bauhaus published the 12th Bauhausbuch Bahausbauten Dessau, a work credited as being edited by Gropius and Moholy-Nagy but in whose production Moholy was closely involved, uncredited, obvs. But is a book, a rare book, in which not only her photos are credited to her, but all photographs are credited to the respective photographers. Strange that. Although does also pose the question why she allowed her photos to be published uncredited in those pre-1928 Bauhausbücher she was responsible for editing. Probably on account of Gropius. The rat. Also interesting to note that certainly in some we've not (yet) checked all of the newly reissued Bauhausbücher in English through Lars Müller, Zürich, Lucia is still not credited, although many of the images are evidently, demonstrably, unequivocally, hers. But that may be more to do with legal complexities than anything else, we've not asked, aren't apportioning blame. But is interesting and important to note. And to be aware of.

7There is obviously also the question of why Giedion didn't ask Moholy for them. Yes, he may have, and she may have said no, but had he, why is there no reference to them in Moholy's letter to Giedion, or Giedion's letter to Moholy as presented in in Exposures, they would have been relevant to the themes of the letters. So one must presume no attempt was made to get Moholy's Denham photos. Why not?

8In terms of Gropius's use of Moholy's negatives there is also the question on the one hand of why László didn't tell Lucia he had give the negatives to Gropius, did he, perhaps, know what Gropius was planning and decided to keep quiet, and on the other why László said nothing when Lucia's negatives were used, uncredited, in the 1938/39 exhibition Bauhaus: 1919–1928 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. But one must also remember that László died, tragically aged just 51, in 1946 as a consequence of Leukaemia and so was either too ill to assist, too distracted by his condition to assist, or wasn't around, when Lucia's search for her negatives brought her to Gropius's denials and attempted gaslighting.

9The 1938 exhibition Bauhaus: 1919–1928 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York was pivotal in helping Bauhaus establish itself in America, of enabling the contemporary Bauhaus legend to become established, to enabling the contemporary Bauhaus narrative to become fixed; and was an exhibtion in which Moholy's photographs often stood proxy for objects that for various reasons couldn't be displayed, in which Moholy's photographs helped set Gropius's atelier building in the desired light, and in which Moholy's photographs helped Gropius set Bauhaus in the desired light, have you spotted the year the exhibition ends. Weird that, always thought Bauhaus existed till 1933. Had Gropius named Moholy in Bauhaus: 1919–1928, who knows how different Moholy's career, and visibility and appreciation, would have been. Or had László stood up for her and demanded Gropius contact Lucia, or at least credit Lucia. László was, lest we forget, unlike Lucia, in America in 1938.

10While very much liking Moholy's description, there is, for us, the very obvious flaw that while a camera is a mechanical tool, that which it does mechanically has to be transformed by human hand in the dark room in to the final object, which is a process very much akin to working with "pencil, chalk, brush, chisel etc." Or does in photography where negatives are developed into photographs, in microfilm you come much closer to Lucia's description. Which again makes her step to microfilm much simpler. And with digital photography one reaches that reality Moholy describes, as long as you don't then don't undertake any post-production, but simply keep that image as taken. Which also helps explain that most of that which is novel is that which once was just in new contexts, with new materials and technology. And thus the ease with which we can learn from that which once was. If we choose to that is.

11Lucia Moholy, A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939, Bauhäusler. Dokumente aus dem Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Band 4, Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, 2016, page 20

12L. Moholy-Nagy, Produktion – Reproduktion, De Stijl, NB Internationaal Maandblad voor Nieuwe Kunst Wetenschap en Kultur, 7, Juli 1922 Was however, despite what the credit says, by both. And, yes, in the text their idea of "productive" purposes includes "to receive and capture light phenomena (light moments) we create with mirrors or lenses etc.", so the experimental photography they worked on in Weimar, but also included X-rays or "Celestial photographs", and we'll argue Lucia's photos as documents is also "productive".