"There is terror and panic in our city", wrote the, then, 14 year old Clara Schwarz of life in, then, Żółkiew, Poland, today, Zhovkva, Ukraine, in the summer of 1942 of life under German occupation, "the Jews are building bunkers of all kinds: underground, double walls, anywhere they can find a spot to hide".1

For Clara and her family that "spot" was a "3 metres square and a meter and a half deep" bunker under a house, a bunker dug out by Clara and other children with their bare hands; a "spot" that saved 10 people from murder and/or deportation in the Gestapo raid of November 1942. And which was subsequently expanded to a "10- by 14- metre" bunker which saved 18 individuals from being interned in the new Żółkiew Ghetto in December 1942. A bunker, a "dank, unsanitary place", under a house, in which Clara her family and neighbours lived for 18 months.

And just one of thousands of hideouts used by Jews across Europe in the 1930s and 40s; thousands for which nine stand proxy in Natalia Romik. Hideouts. Architecture of Survival at the Jewish Museum, Frankfurt, an exhibition which aside from helping focus attention on the terror, brutality and inhumanity of the NSDAP and standing testimony to those men, women and children forced to endure that terror, brutality and inhumanity, allows for differentiated reflections on both concealment and on the built environment, on the complexity of our relationships with the environments we build.......

Arising from a long running, and still ongoing, interdisciplinary research project by Warsaw based architect and historian Dr. Natalia Romik, and previously presented at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, and the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Natalia Romik. Hideouts. Architecture of Survival approaches it themes and discussions from two perspectives, one artistic, one academic.

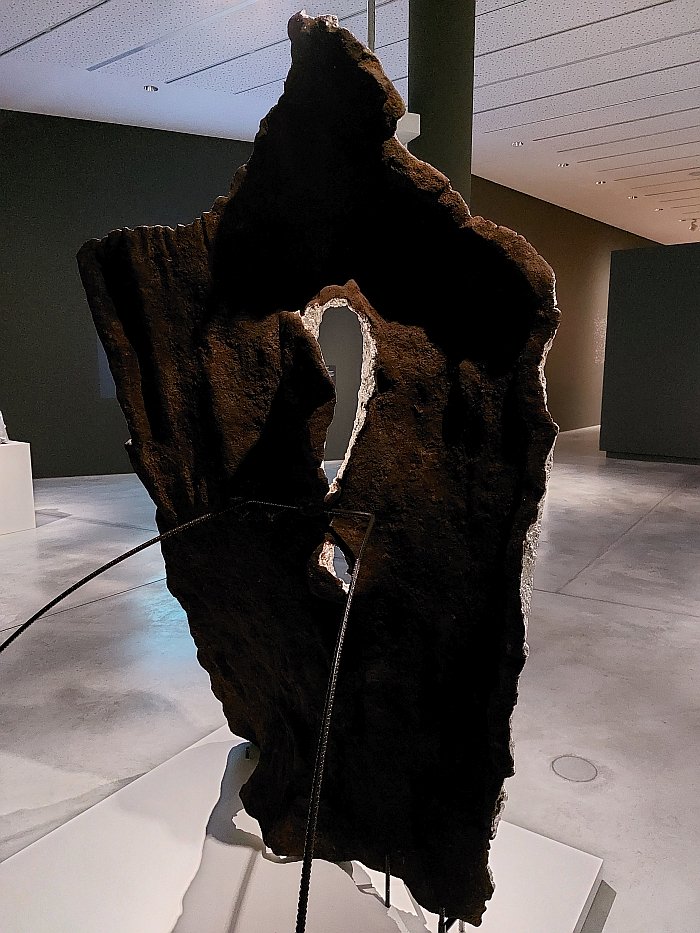

The former a collection of nine casts, one from each of the nine featured hideouts, hideouts spread across the contemporary Poland and Ukraine and including the sewers of Lviv which one learns were home to dozens of individuals for over a year; the so-called Józef oak in Wiśniowa, a hollowed out, 'chimney', tree, within which the brothers Dawid and Paul Denholz sought refuge after escaping from the Plaszów concentration camp; the Ozerna cave near Czernowitz, a hideout equipped with a quern for grinding grain to feed the 38 individuals sheltering there; a cellar in a monastery in Jarosław accessed through a secret door in the back of a wardrobe, which for all the parallels it has with C.S. Lewis's The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe probably wasn't a door to a fantasy kingdom for those children obliged by necessity to pass through it. And the "10- by 14- metre dank, unsanitary place" within which Clara Schwarz, her family and neighbours resided for 18 months; a hideout presented in Hideouts. Architecture of Survival by a cast of the outline of the entrance as cut in the parquet floor of the house by Mr. Patrontasch, an entrance which, when in place, "the seam, like the opening to a Chinese box, was impossible to find".2 But which as a gaping, open cast in a museum reveals not only the secrets of its construction, but its raison d'etre, that which it so diligently and conscientiously sought to hide.

And a cast, as with all the others, that expresses itself with a high-gloss silver side and dark, earthy, side; a bifront on the one hand symbolic of the light and dark within and without the hideout, and also of the light and dark of a society that forces individuals to seek hideouts. And also, certainly in context of the silver side, or perhaps more accurately in context of the silver side in discourse with the dark side, plays very neatly with both the invisibility, anonymity, the hideouts had to present to the casual viewer, or the suspicious German soldier, that principle of being "impossible to find", and also plays with that disguise through glitz and glamour and bling and reflected image of any society and any life, that shimmering facade of 'everything's OK', 'nothing to see here' we all cloak ourselves in.

The latter featuring a series of vitrines presenting archival and contemporary research documents, photos, objects etc which describe and discuss the processes of the nine hideouts' 1930s/40s creation and 2020s documentation in more detail, including elucidating the myriad difficulties and obstacles in writing the (hi)stories of many of the hideouts, and by extrapolation indicating the number of hideouts whose existence has been forgotten and may never be recovered. And a presentation which also provides for the briefest of insights of life in those hideouts through recollections of some of those who employed the hideouts, through 3D scans of the hideouts, through artefacts found in the remnants of the hideouts, and through the presentation of an actual hideout, specifically a wardrobe found by chance in a house in Huta Zaborowska, more or the less in the exact centre of the contemporary Poland, and in which an as yet unidentified individual took refuge for an as yet unknown period. A wardrobe also featured in Hideouts. Architecture of Survival as a cast of its door; and a wardrobe which helps reinforce not only the "anywhere" the 14 year old Clara Schwarz spoke of, but also the urgency, the immediacy, the inescapability, of the need that led to the creation of the thousands of hideouts.

An approaching of the themes and discussions from two different, yet mutually supportive and complementing perspectives, that reinforces not only the horrors of the reality the individuals involved lived through, nor only the inhumanity that forces individuals to seek hideouts, that "man's blind indifference to his fellow man" of an Eric Bogle3, but also pays tribute to the resourcefulness and resolve of those who built and used the hideouts.

And a two-pronged approaching of the themes and discussions which very naturally encourages you to reflect on and to consider the nine hideouts and the biographies of those associated with them in wider, alternative contexts.

The most obvious of which, the most inescapable of which, are those reflections and considerations arising in context of the current realities in the contemporary Israel and Palestine, including, as arguably the most direct of innumerable thoughts and considerations, the bunkers that are such a ubiquitous feature in many Israeli towns and cities. And also those reflections and considerations arising in context of the current realities in the contemporary Ukraine, a Ukraine that, as can be seen on a map presented in Hideouts. Architecture of Survival depicting the locations of known hideouts in Poland, Ukraine and Belarus, a map that, and digressing widely, bears an uncanny resemblance to Wales, and thereby also bears an uncanny resemblance to a pig's head, a comparison, an arbitrary similarity, that is as grotesque as it is poetically supportive of those in the hideouts.... a Ukraine that, as can be seen on a map in Hideouts. Architecture of Survival depicting the locations of known hideouts, was home to innumerable hideouts; and a Ukraine where neigh-on a century later untold numbers have to seek either more or less permanent hideouts, "a spot to hide", from Russian soldiers or regularly seek temporary hideouts from Russian bombs and drones. The city of Lviv where the Jewish residents once took refuge in the sewers currently provides online maps of underground shelters in case of attack; and while the sewage system is no longer used the more contemporary metro system is, which while it may be more comfortable, is no less awful a reality. While a little to the north of Lviv the hideout in Żółkiew/Zhovkva used by Clara Schwarz, her family and neighbours is still there.4 Still silently hidden in the parquet floor like the "opening to a Chinese box" as crafted by Mr. Patrontasch. Still ready to be used. Comparisons of 1930s and 40s Poland and Ukraine with 2020s Israel, Palestine and Ukraine which remind of New Model Army's charge that we "blind yourselves with comfort lies like lightning never strikes you twice"5, and then are amazed when it does, with the very obvious question of why we've been struck not twice, but three, four, five, untold times. And will invariably be struck again. Why as a species are we so utterly unable to learn from the past? It's not as if the lessons aren't out there.

And also encourages and enables reflections and considerations on those great many globally who today are forced to hide from their governments, hide from those (theoretically) tasked with protecting and supporting them, be that, for example, LGBTQ+ individuals in a great many countries, or those seeking or who have had abortions in a great many countries and US States, or those whose religious beliefs deviate from that of the State, or girls seeking an education in Afghanistan or those providing girls with an education in Afghanistan.

Or reflections and considerations on that peculiar human habit of 'hiding' in the everyday, of concealing ourselves away in full public view, although there is no real, no tangible, danger; that peculiar human habit of presenting a public facade which appears as high-gloss and shiny as the silver side of the nine casts on show in Hideouts. Architecture of Survival, but which is just that shimmering facade of 'everything's OK', 'nothing to see here', we all cloak ourselves in for fear of being caught. That way we seek to blend in with our surroundings like Mr. Patrontasch's bunker entrance through reflecting the image of those around us, for fear of exposing the private below the public facade. Be that, for example, in context of doing a job that brings you nothing but you feel obliged to continue in for whatever reason; being in a relationship you know is going nowhere but you feel obliged to continue in for whatever reason; living in a town that alienates you but you feel obliged to remain in for whatever reason; having a dream of which you daren't speak for fear of what others will think and say and do, etc, etc, etc. We all do it. Not all the time, but repeatedly. The biographies of those who in 1930s and 40s Europe had no option but to seek a hideout, and the biographies of those millions globally who today have no option but to seek a hideout, forcing you to question why we all do it in our safe daily lives. We have choices. Why do we choose to hide behind a shimmering facade? Why the reflected image? Why the 'everything's OK'? Why the 'nothing to see here'? Why seek the darkness and claustrophobia of a hideout you don't need, for which there is no urgency, immediacy, inescapability? What's the risk in being honest? What's the risk in being (in the) open? In early 1940s Żółkiew the risk was horrendous, but in your contemporary reality...?

In addition, and for all that Hideouts. Architecture of Survival is without question an exhibition about the violence and inhumanity of the human species and the resourcefulness and resolve of the human species, about human beings in times of extreme danger and violence, about acts of bravery and betrayal, about the terrifyingly close proximity of banality and brutality in everyday life, about encouraging, empowering, us all to learn from the lessons of the past and to question our personal, private, hideouts, it is also an exhibition about the Architecture of the title, an exhibition that initiates discourses on construction, homes, the built environment, interior spaces, etc. An exhibition that initiates discourses on architecture.

Discourses Hideouts. Architecture of Survival allows one to approach from numerous informative perspectives; differentiated approaches opened by Hideouts. Architecture of Survival that very real limits of time, and, ironically, space, regrettably, preclude us from fully entering into here, mean we must leave for another day. We wish it wasn't so, but sadly is.

Save to note here the reflections enabled, demanded, by Hideouts. Architecture of Survival on the way relationships with spaces can and do change over time, without the space itself physically changing, a reality alluded to, for example, by the fact that Ozerna cave, that secret hideout, was widely known before the 1939-45 War and was, by all accounts, a popular tourist attraction in the region, something attested to by pre-War tourist graffiti, including pre-War graffiti indicating Jews were in the cave, enjoying the cave network, as a location of relaxation, adventure and fun; while the caves themselves would have been (more or less) physically identical in 1953, 1943, 1933, 1923, etc, the relationships with the space, the appreciations of the space, the value and meaning and memory of the space were very, very different.

Appreciations also approached by the discovery within the interior of the Józef oak in Wiśniowa of a series of planks and brackets, planks and brackets that could be used, for example, as steps or seats, thereby making the interior of the tree a functional space. Planks and brackets that, according to Natalia Romik, pre-date the 1939-45 War and which thus tend to imply that the oak was used as a hideout before that war. An implication which causes you to ask by whom? For what purposes? How do they and their purposes stand in relation to the Denholz brothers and their purposes? Did the Denholz's know about the steps and brackets, or did they get lucky? But certainly to appreciate that the space within the Józef oak had a reality, an existence, a value, relationships, memories, before those of and with the Denholz brothers. Much as the Ozerna cave did before it became a hideout. Much as most all of the nine featured spaces did before they became hideouts.

Appreciations on changing relationships with space which it's very simple to transpose onto other scenarios, into other contexts, into other periods, into your spaces, experiences, life. Appreciations which also help underscore that relationships with spaces are not only transitory, volatile, active, but invariably simultaneously private and public, are simultaneously collective and individual. And which as such are important components of the discourses on construction, homes, the built environment, interior spaces, etc, discourses of architecture, Hideouts. Architecture of Survival initiates, but we will, sadly, have to leave for another day.

And save to make note here of the opinion of the American architect and author George Nelson, a highly astute observer of human society in its natural and self-built environments, that "the creative freedom from which we sometimes talk is nothing compared with an effective response to the pressures of necessity"6; urgency, immediacy, inescapability as enablers of solutions that would otherwise escape us, or as Nelson claims "the best human designs are survival designs"7, and that, arguably, exactly because of the fact the user is 100% dependent on their correct functioning, and that there is no time to over-think or over-tinker. Opinions and positions that very naturally accompany you as you travel through Hideouts. Architecture of Survival, that provide an alternative framework in which to view Hideouts. Architecture of Survival, provide a new level of questioning. And which also allow one to extrapolate the nine featured hideouts into considerations on the architecture we'll need to survive the ever warmer and ever more hostile climate we seem determined to create. To reflect that whereas until now architecture of survival was often limited to a few extreme situations, and often about making do with what was at hand, such as a wardrobe, a sewer or a tree, in the tangible future it could very well become one of architecture's primary foci. And an architecture of survival we will return to another day.

And save to note that Hideouts. Architecture of Survival helps reinforce that for all architecture has long been associated with beauty, it needn't be. For all architecture has long been associated with the positive, with progress, it needn't be. As exhibitions such as, for example, and remaining very much in context, Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, or Bauhaus and National Socialism at Klassik Stiftung Weimar help elucidate, and Hideouts. Architecture of Survival tends to confirm, architecture can be ugly, offensive, distasteful, dangerous, violent. As can life. And to focus on the beauty alone, the positive alone, the progress alone, be that of architecture or life, is to do oneself and ones fellow humans a massive disservice. And also to fail to recognise the inherent connections between human society and the structures we create, to fail to recognise the two-way relationship between a human society and the environment it builds for itself, that way we influence it and it us. The way it reflects us and we it.

And save to opine that while Hideouts. Construction for Survival would make sense as a title, we'd argue it falls a long, long way short of encapsulating and mediating the realities being discussed. Hideouts. Architecture of Survival is and was the correct option.

An intelligently designed exhibition which despite the nature of the material involved, nature of the themes presented and of the discussions initiated is a very accessible, approachable exhibition; a bilingual German/English exhibition that despite the personal biographies at the core of its narrative never becomes voyeuristic, maintains an objective distance, remains focussed on its themes and discussions and the hideouts. And an exhibition that gives you the time and space to not only find your own way through the two component parts but to form your own connections between the two, to bring the two in a dialogue with each other and which encourages you to then take the dialogue thus begun outwith the Jewish Museum, Frankfurt.

To take the hideouts and the biographies outwith the horrors of the Holocaust and allow them to serve as conduits for differentiated approaches to a great many contemporary themes, conduits to approaching a great many contemporary themes afresh, anew; while always reminding you that the hideouts and biographies are part of the (hi)story of the Jewish people, and part of the (hi)story of Europe.

Is a reminder, a timeous and apposite and powerful reminder, of the importance of an objectively and thoroughly documented (hi)story of human society, a reminder that everything is part of the path we've taken thus far and the importance of acknowledging that and actively engaging with that in all its facets. The importance of not trying to conceal (hi)story, of not coating (hi)story with a shimmering facade of 'everything's OK', 'nothing to see here', but of looking beyond the glitz and glamour and bling and reflected image into the darkness. Of getting to know the most unhygienic, dankest, corners of the bunkers.

Natalia Romik. Hideouts. Architecture of Survival is scheduled to run at the Jewish Museum, Bertha-Pappenheim-Platz 1, 60311 Frankfurt until Sunday September 1st.

Full details can be found at www.juedischesmuseum.de

In addition a catalogue that goes into the themes and discussions and research in more detail is available via Hatje Cantz Verlag.

1Clara Kramer, Clara's War, McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, 2008 page 40 The diary entry quoted is undated, the chapter it introduces covers July 1941 to November 1942, we are assuming, based on the developments described in the chapter, that it was written in the summer of 1942. Clara Schwarz/Kramer's birth date is only given as '1927', so depending on if the diary entry was made in 1941 or 1942 she could have been 13, 14 or 15. We plumped for 14, we could be wrong. Apologies.

2ibid, page 53

3Eric Bogle, No Man's Land, 1976 available in various versions on numerous of his albums. Our personal go to version, and with no offence to Eric, is that by The Men They Couldn't Hang on their 1985 album Night of a Thousand Candles. But that's just our opinion.

4FN 1, page 336.

5New Model Army, I Love the World on Thunder and Consolation, EMI, 1985

6George Nelson, Design: The business of survival, Industrial Design, March 1975

7George Nelson, Zum Design von Sportgeräten, Du: die Zeitschrift der Kultur, Vol 36, Nr. 7, 1976