Born in Aschaffenburg, Bayern, on March 30th 1938 into a family of small traders, her mother's family running a butchery, her father operating a drugstore, Dorothee Becker enjoyed, a, by all accounts, happy, comfortable, childhood on the Bavarian/Hessen border, if an early biography that is still to be fully told. After completing her secondary education Becker enrolled at, attended, the universities in Frankfurt and Munich, again that dual Hessen/Bayern thing, where her primary focus was, by all accounts, Anglistik and Amerikanistik, English language and literature and American Studies, if as far as we understand, she never formally graduated from either institution. In Munich Becker did however meet the young graphic designer Ingo Maurer whom she married and with whom she spent a year in the early 1960s living and working in San Francisco, before returning to Germany where, in the mid-1960s, Maurer, as discussed from Ingo Maurer intim. Design or what? at Die Neue Sammlung – The Design Museum, Munich, established the design company Design M as a platform for producing and distributing his designs, his new focus on 3D rather than 2D design, and for all his lighting designs. Whereby, as aus dem persönlichen Nachlass — literally from the personal estate, but also, in many regards, from that which remains, a statement of fact as much as exhibition title....... — whereby as aus dem persönlichen Nachlass allows to better appreciate the "his" of that period can be considered a contentious phrase. And a mid-1960s, late-1960s and early-1970s to which we shall return shortly, save to note here that in that period Maurer and Becker separated. And that, as aus dem persönlichen Nachlass tends to imply, not particularly amicably.

In 1976 Dorothee Becker, by now a single mother with two (approaching) teenage daughters, established the designer store Utensilo in the Herzogstrasse in the Schwabing district of northern Munich, arguably following in her family tradition, but also very much a response to her prevailing economic realities; a design store through which she sold works by third parties alongside her own designs, and all of which were works she considered "gute brauchbare Sachen", 'good practical things', and certainly not "Schnickschnack" "superfluous frilly knick-knacks. I despise such objects ... objects should be practical: good and pleasant to look at".1 Or as the adjunct to Utensilo announces: praktisch & schön. Practical & beautiful. And a Utensilo store in which, as one learns in aus dem persönlichen Nachlass, Becker discovered a creative joy, a creative energy, in display window decoration; an expression in which she combined her passions for good design, aesthetic satisfaction and the natural world.

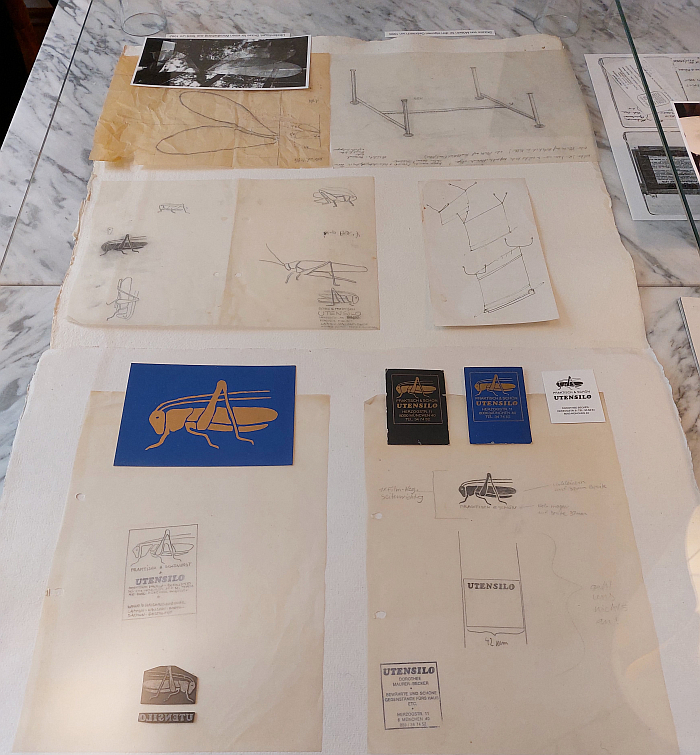

A natural world that Becker not only regularly immersed herself in, found inspiration in and employed in her works, the Utensilo logo is and was a cricket, an insect, one learns, whose Sprungkraft, jumping power/springing power, Becker greatly admired. An admiration that may or not have a metaphorical basis. And a natural world Becker sought to protect; in the 1980s being active in environmental protection and anti-nuclear movements. An activism that, in many regards, can also be understood in her successful legal challenge to ensure that her daughters didn't have to take the, in 1970s Bayern, compulsory for girls sewing and needlework classes but could attend the carpentry classes along with the boys. Not that Becker was opposed to textile work per se, as one can appreciate in aus dem persönlichen Nachlass she worked in textiles, and that in various contexts and genres throughout her career, but she was very aware of the separation between male and female creative practice, and of the realities that textiles were exclusively female. And, reading between the lines, a bit of a dead end. A state of affairs that, as oft noted and bewailed in these dispatches, remains in the contemporary furniture industry: where females are retained by furniture manufacturers, then invariably in context of fabrics and colours. It is changing, but....... And activism in its various forms that, again as aus dem persönlichen Nachlass tends to imply, was a direct consequence, a direct continuation of an, let's say, awakening in Becker in context of the social, cultural, civic and political questioning and challenging of the late-1960s.

In 1989 Becker closed Utensilo, the exact why being again, uncertain, and devoted herself to a variety of, largely private, creative occupations, including carpets: she wasn't fundamentally opposed to females doing textiles, just opposed to the compulsion to. And limitation to.

Dorothee Becker died on April 29th 2023, aged 85.

Complied and arranged by Claude Maurer, daughter of Dorothee and Ingo, together with her partner Frank Koschembar, aus dem persönlichen Nachlass allowed for an introduction, the briefest of introductions, to the varied and various expressions of Dorothee Becker's creative output, featuring as it did examples of her lighting, textile, graphic and product design work. An introduction that very much implied that there is a lot more learn. A lot more.

A presentation that for all its brevity also allowed not only for a placing of her most popularly known design, arguably popularly only known design, the Uten.silo organiser, a product originally released in the late 1960s by Design M before being re-issued by Vitra, in context of her wider work, but which also allowed for insights into its genesis: one could effortlessly follow how a wooden kids puzzle, a toy that also helps encourage creativity, curiosity, motor concentration and 3D spatial interpretation, became an organiser for adults and kids alike. It is essentially the same thing: decisions have to be made what goes where, whereby objects don't have to fit exactly in any one locations, just fit comfortably, and in a way that means they can removed again. If a wooden puzzle that exists, at the moment, in but one photo. A photo that also confirms the physical, formal, graphic similarities with Uten.silo.

A presentation that for all its brevity also allowed one to better approach the person Dorothee Becker, not just Dorothee Becker the creative, making note as it did of not only her activism and battles but also her positions on and to feminism: "ich bin selbstverständlich eine Feministin" she proclaims from a 2010 interview, "I am very a much a feminist", continuing that, "for me that means that I not only want and demand the same rights, but also the same chances in life".2

And a presentation that for all its brevity, through elucidating, through discussing, Dorothee Becker's life in the mid-1960s, late-1960s and early-1970s also helps one begin to better approach an inkling of why Dorothee Becker is today so anonymous, so reduced to one product. If a truly engaging product. For while there are invariably innumerable inter-twinned and inter-dependent reasons for Dorothee Becker's contemporary anonymity, a lot more research is waiting to be completed, aus dem persönlichen Nachlass highlights, locates, Becker in one the many reasons, arguably one of the more common reason, that female creatives become anonymous: no-one records their contribution to those works associated with the much more popularly visible husband. Works associated with the husband alone. Something we discussed in context of Lucia Moholy and László Moholy-Nagy from The Image of Modernity at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, that fact that for all that Lucia unquestionably contributed to many, ¿all?, of László's early experiments and projects, the fact that no-one recorded the contributions, no-one kept detailed notes, an actual physical reminder of what was undertaken and discussed, later on it was all László, who became the household name. While Lucia became Who She? A muse 🙄 aus dem persönlichen Nachlass allows parallels with Luicia and László to be drawn in Dorothee and Ingo; we're not saying exact parallels, for that we have far too little information, and we weren't there at the time, we now know, but the implication through viewing aus dem persönlichen Nachlass is very much that Maurer's works in the 1960s and early 1970s arose in conversation with, in context of, and through input from Becker. Whereby the degree isn't recorded. Which would be important. Not that joint projects don't exist today, they do, for all in the form of the so-called Scherenlamp, Scissors Lamp, a work first released in 1968 by Design M, and on show in aus dem persönlichen Nachlass in both the table and wall version, a work that was, and is also recorded by the Ingo Maurer intim. Design or what? catalogue as, a joint Becker/Maurer product. aus dem persönlichen Nachlass implies there could be more. Perhaps many more. While also making it clear that we'll probably never know. And a reality, inarguably, faced by a great many female creatives of the past, that, inarguably, is still being faced by a great many today. Because in the flush of creativity with a professional and personal partner, no-one thinks to make notes. And then the female falls away into the pitfalls and traps of (hi)story . Always keep records of all conversations and time spent in the workshop. No, it's not romantic, but neither are long-term relationships.

In addition, again arguably, again we have no actual evidence for the following, just a strong gut feeling having viewed aus dem persönlichen Nachlass....... in addition, Becker's status as single mother in 1970s Bayern, arguably, greatly impaired and obstructed her further creative development, and that at a period when she was starting to pick up real speed. And that despite the 1970s often being considered an advanced, enlightened even, period, but which as a Dorothee Becker helps elucidate wasn't that far removed from the 1860s and 1870s as far as gender equality was concerned. Certainly in West Germany, the only context in which one can consider a Dorothee Becker. Or possibly only Bayern. Girls doing sewing, boys doing woodwork. And, again, a situation, a requirement to halt one's career to focus on childcare that a great many female creatives of the past knew, others sacrificing motherhood aware of what would happen. And also, inarguably, experienced by a great many today in times that, for all the social and civic advances, are, arguably, more comparable with the 1920s than the 2020s as imagined in 1968. A contemporaneousness that Dorothee Becker was aware of, the aforementioned 2010 quote running in its full length, "for me that means that I not only want and demand the same rights, but also the same chances in life. And that is still not the case today".

Through Utensilo Becker, arguably, found a way to carve her own creative path despite the problems, a way to take the same rights and possess the same chances in life regardless of what the patriarch insisted and dictated, regardless of the pre-defined path the patriarch laid down. Utensilo as a form of feminist resistance. Which isn't to say that Uten.silo is a symbol of feminist resistance. But, ya know......

More observant reader will have understood from our use of the past tense in context of aus dem persönlichen Nachlass it has now finished, for less observant readers: it has now finished. The curse of any design week being that showcases vanish before they've had a proper chance to introduce and establish themselves.

And as far as we understand aus dem persönlichen Nachlass will remain a one-off: but we do hope someone can convince Claude and Frank to recreate the presentation. Or to use it, and any additional objects, as the basis for a larger project; and we're sure that if one or the other museum had an honest look in the archives they'd find one or the other object that could, with a little reference to and information from aus dem persönlichen Nachlass, be more correctly labelled and thereby help contribute to that larger project. And a more complete apprecaition of the creative Dorothee Becker.

A larger project we hope arises because as a showcase aus dem persönlichen Nachlass not only offers insights into the work of Dorothee Becker, and the life of Dorothee Becker, and the connection between the two that are normally, unseen, and also helps explain the links between the two, but also allows Dorothee Becker to stand as a conduit to explain how we arrived at our skewed narrative of the (hi)story of design, how we can go about trying to write more probable narratives, and also, and arguably more importantly, prevent future narratives becoming as skewed as those we have. And also allows Dorothee Becker to stand as a conduit to explain the social, cultural et al realities in 1970s West Germany; her biography is almost certainly one that finds innumerable echoes. Echoes that also need to be told in the original.

But for all through presenting example of works from across the genres and periods of her creativity, and through elucidating her role in the development Design M, aus dem persönlichen Nachlass allowed and allows Dorothee Becker to begin to shake of her cloak of anonymity, to move beyond Uten.silo, joyous as it is, and to begin to retake her place on the helix of design (hi)story.

aus dem persönlichen Nachlass was staged at Raum für Reflexion, Aquinostrasse 13, 50670 Cologne between Friday January 12th and Thursday January 18th in context of the 2024 Passagen Interior Design Week Cologne.

1As quoted in aus dem persönlichen Nachlass. The reference was given as a chapter by Dr. Martina Fineder in the book Aesthetic politics in fashion, Elke Gaugele [Ed.], 2014, we however can't find the quotes in that book, and suspect that they are actually from an unpublished interview by Fineder with Becker on which the chapter was based. Or we're just being supremely daft. Dafter than normal. We're on the trail and will update once we have more.

2As quoted in aus dem persönlichen Nachlass. Unpublished 2010 interview with Dorothee Becker undertaken by Dr. Martina Fineder.