"How did I end up going to technical school?" asked once the Finnish architect Wivi Lönn, rhetorically, "I had building in my blood, and it pulled me in."1

With the exhibition Long Live Wivi Lönn! the Museum of Finnish Architecture, Helsinki, help elucidate not only how that innate urge expressed itself, but also that for all the apparent ease contained in Lönn's account of an innate urge being followed, for a Wivi Lönn, and for the great many Wivi Lönn's over the past 200 years, it wasn't that simple, if every bit as self-evident.......

Born in Tampere on May 20th 1872 as the second child to Wilhelm and Mathilda Lönn, her father a Master Brewer, Olivia Mathilda "Wivi" Lönn enrolled in 1892 in the Master Builder course at Tampere Technical College, becoming only the second ever female to enrol, to be allowed to enrol, at the Tampere college.2 Following the completion of her one year course, and on the recommendation of her tutor Georg Schreck, Lönn moved to Helsinki and the Polytechnic Institute where in 1896 she became the 5th female in Finland to graduate in architecture; whereupon Lönn initially worked as a draughtswoman in the practice of Gustaf Nyström, the, then, Director of the Polytechnic Institute, before the award of a scholarship enabled her to undertake a three month study tour in 1898 through Germany, England and Scotland. 1898 also seeing Wivi Lönn return to Tampere where she established her own architectural practice, and that as the very first female in Finland to run their own architectural practice, the very first female in Finland to practice as an independent architect.

A practice established, primarily, to allow Wivi Lönn to complete her first commission: that for the Finnish Girls' School in Tampere. Whereby the "Finnish" of the name is not irrelevant for, lest we forget, at this point in (hi)story Finland is still formally the Grand Duchy of Finland, an autonomous region within the Russian Empire. If one moving ever quicker, and ever more self-confidently, towards independence.

And a Finnish Girls' School, completed in 1902, where, in effect, Long Live Wivi Lönn!, opens with a brief introduction to the project in words and pictures; and which leads into similar brief introductions to a further nine projects by Wivi Lönn from across the first decades of the 20th century. A tour which takes one to works such as, for example, Tampere Fire Station completed in 1908, a commission received in context of a competition, one of numerous competitions Lönn won throughout her career, and whose granite facade places it very much in the National Romantic movement of the period, that, if one so will, Finnish, Nordic, expression of Art Nouveau; a house for herself and her mother in Jyväskylä from 1911, a work in a town that, not uninterestingly, was also important in the biographies of Lönn's younger contemporaries Aino and Alvar Aalto, a work which features a greenhouse-cum-conservatory that, judging by the photos we've seen, appears to have crashed into the house at an obtuse angle, although not unattractively so, on the contrary it appears a most aesthetic, satisfying, if incongruous, connection of two forms, two objects; the Estonia Theatre in Tallinn completed in 1913, a work realised in cooperation with her former Polytechnic Institute contemporary Armas Lindgren, one of several projects Lönn undertook with Lindgren following his departure from his famed, and very important, partnership with Eliel Saarinen and Herman Gesellius, a project in which Lönn was responsible for the interior spatial layout and form while Lindgren authored the exterior and the overall form and scale, and thus Lönn, arguably, responsible for the more important part, the architecture not the art, and a project in Tallinn which helps underscore the lands bordering the Gulf of Finland as being, for all their apparent dissimilarity, a region with a long shared (hi)story; or the YWCA hostel and offices in downtown Helsinki completed in 1928, a project realised with a reserved but far from mute expression that references the motifs and components of classical architecture while also actively distancing itself from such, and which very much intimates a change is a coming, and a project which included an apartment on the top floor for Lönn and Hanna Parviainen which the two shared until Parviainen's death in 1938, aged just 63, and which Lönn continued to occupy until her own death in 1966, aged 94. And a brief tour which ends with the 1933 YWCA building in Savonlinna on the shores of, in the middle of, Lake Saimaa, an expansive water landscape in south-east Finland and which as the curators note marks Lönn's last significant work, a moment on a gradual drifting into retirement throughout the 1930s. And also represents a work formally and conceptually far, far removed from the Finnish Girls' School in Tampere where the brief tour began.

A journey from Tampere to Savonlinna undertaken in the company of works by Wivi Lönn that not only helps elucidate the journey Wivi Lönn's positions and approaches took during her 30-ish year active career, but also helps elucidate the variety of projects she developed, both in terms of typology and geography, helps explain the varied and various circles in which she moved, helps introduce her understandings of the roles and functions of architecture and of architects, helps guide you through her use of space and her setting of relationships within space to enable a building to contribute to the life that occurred within it rather than simply housing it, her take, if one so will, on the relationship between form and function, and thereby very much helps one locate and place Wivi Lönn in the Finnish and European architecture of the first decades of the 20th century.

And a journey that also allows the Museum of Finnish Architecture to employ Wivi Lönn as a conduit via which to both elucidate the realities of and for women in early 20th century Finnish architecture and also to stimulate a discussion on the realities of and for women in international architecture since the early 20th century.

The former undertaken parallel to a discussion on the wider realities of and for women in early 20th century Finland, including brief mention of, brief discussions on, for example, university education or the difficulty of acquiring such, prevailing social pressures and norms, the employment opportunities open to professional females, the necessity of the age for females to choose between marriage or a career, married women being denied the latter, or the male dominated and orientated networks and frameworks of Finnish society and politics. Or more succinctly put: discrimination. Mixed with prejudice. And fear. Thereby enforcing inequality. Obstacles which, as the curators note, meant that the greater many females hoping to become architects in late 19th/early 20th century Finland either neither received the opportunity, or when they did were either actively hindered in establishing themselves or worked in an office as a then unnamed, thus now anonymous, invisible, member of a male architect's successful, visible, celebrated, practice. To which they contributed.

Obstacles, discrimination, prejudice, fear which were also placed in Wivi Lönn's path; Long Live Wivi Lönn! noting, for example, the open hostility Lönn faced when she won the 1903 competition for the Aleksanteri elementary School in Tampere, or the somewhat dubious, fishy, nefarious manner in which her winning entry for a 1908 competition for a new volunteer fire brigade station in Tampere, not to be confused with the professional fire brigade station noted above, was suddenly ditched and a losing project by a man realised in its place. And we'll let you all interpret and respond yourselves to the praise afforded Lönn by the aforementioned Gustaf Nyström with the commendation, "our little girl draws like a man".3 But would add the Nyström was, as best we can ascertain, an important facilitator and advocate for the young Lönn, appears to have recognised and understood her talents and was genuinely keen that she should be allowed to employ them. Which is an important context in which to consider his late-19th century patriarchal patronising.

Obstacles, discrimination, prejudice, fear which Lönn navigated. Whereby the details of that navigation aren't part of Long Live Wivi Lönn! As an exhibtion Long Live Wivi Lönn! states what Wivi Lönn built, which is without question important, but, we'd argue, equally important is knowing, for example, more specific details of the organisation of the resistance she faced, the arguments she employed, the methodology by which she employed them, the networks that supported her, or how she picked herself up from the invariable knock-downs along the way, such as, for example, the escapade surrounding the new Tampere volunteer fire brigade station, which from this distance stinks of corrupt sexism, with a hint of corrupt misogyny. "I had building in my blood, and it pulled me in", it wasn't that simple.

And a focus on the whats not the hows in navigating early-20th century Finland as an independent female architect which underscores that Long Live Wivi Lönn! features a lot of Lönn's work but a lot less of Lönn's biography. Yes, it's an architecture exhibtion, it should focus on the protagonist's work not the life of the protagonist, we get that; but, on the one hand, and as regular readers may have noticed, we do like a biography, we're always looking for the biography, and on the other, and more fundamentally, there's that question approached by Julian Barnes in his 1984 novel Flaubert's Parrot as to whether it's important to know about an artist's life or if their work suffices, Gustave Flaubert himself once stating that "l'artiste doit s'arranger de façon à faire croire à la postérité qu’il n’a pas vécu", the artist must manage to make posterity believe that he did not live.4

Should they? Must they?

A question we'd always answer through arguing that the life isn't irrelevant to the work: any creatives work is not only a reflection of who they are and where they've come from, but how they responded to and related to the times and the realities through which they lived and in which context any given work arose. Yes, the focus should be on the work, but the context is important, including the personal. And thus we'd always argue for as much biography as can be conveniently included without disrupting or skewing the flow of the exhibition's narrative.

Specifically so in the case of Long Live Wivi Lönn! where the biography could, arguably would, allow for an informative and instructive alternative viewing of the second part of the exhibtion.

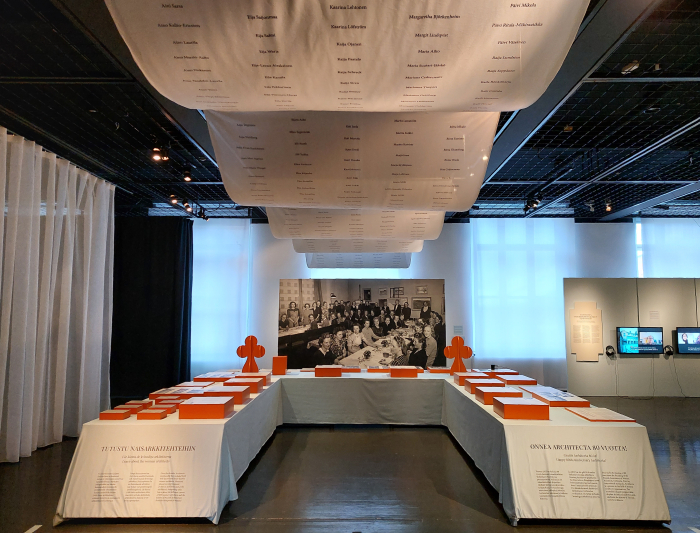

In 1919 a group of young female architects associated with the Helsinki University of Technology, if one so will a second generation of Finnish female architects, established the club Tuumastukki - Yardsticks - as a counterweight to the Finnish Association of Architects from which, as females, they were excluded; as previously noted, one should never, ever, confuse females being allowed to study something with gender equality in that profession. Certainly not in our oh so enlightened age. "I had building in my blood, and it pulled me in", it isn't that simple. A club that although it remained small, there being but 12 Yardsticks, or perhaps more accurately 12 tuumaa, inches, in the Yardstick, wasn't without its influence, including as it did amongst its members the likes of, for example, Aili-Salli Ahde, Elsi Borg or Aino Marsio, later Aino Aalto, who would all make their mark on 20th century Finland. And the 12 tuumaa also formed the early core of Architecta, an organisation established in 1942 as the world's first ever formal association of professional female architects; and an association instigated on the occasion of a dinner attended by dozens of female Finnish architects of all ages to celebrate Wivi Lönn's 70th birthday. Wivi Lönn, one can confidently argue, being very much the figurehead of the ambitions and motivations and disquiets and hopes embodied in Architecta's establishment, a, if one so will, role model for all those other architects present, that outrider, one of those outriders, who had helped forged a path through the obstacles towards an increasing popular acceptance of female architects, an architect who through overcoming the tribulations of her career, and the tribulations of the earliest decades of 20th century Finland, had helped enable much easier paths for coming generations; and although those paths were still strewn with obstacles, obstacles of a different nature in the different social and political contexts in which they were formulated by dominant groupings, a Wivi Lönn had confirmed that they are but obstacles, not barriers, and there were, are, ways past them.

A Finnish association of professional female architects approached in Long Live Wivi Lönn! by discussions and considerations on its roles, relevance and members; in context of the later by introductions to the work and careers of 10 members from across the eight decades of the organisation's existence who stand proxy for all its members and the ever changing contexts and realities in which they worked. And specifically in the persons of Elissa Aalto and Aino Aalto a reminder of the large, all-engulfing, shadow cast over the (hi)story of architecture by male architects.

And a Finnish association of professional female architects that has been joined over the decades not only by a great many other national female architects associations, but also by numerous international networks and platforms for not just female architects but all architects outwith the traditionally dominant groupings.

Developments discussed in Long Live Wivi Lönn! via a, more or less, chronological timeline of international events, platforms and organisations initiated since the 1970s not only striving for, campaigning for, taking, more opportunities for female architects and more visibility for female architects but also striving for, campaigning for, developing, a less male-centred architecture, a move away from the dominant male gaze in the design of buildings and spaces, and advancing the appreciation that in architecture and urban planning the drawing "like a man" which so impressed a Gustaf Nyström is a problem, and that architects should, must, stop drawing like men. Urgently. And also events, platforms and organisations facilitating and enabling greater self-organisation amongst not just females but all marginalised groupings.

Events, platforms and organisations such as, for example, the 1977 exhibtion Women in Architecture at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, organised in conjunction with the Archive of Women in Architecture; the feminist co-operative Matrix established in London in 1980; the research group FATALE founded in 2007 at the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm; the many, many tribulations of Denise Scott Brown, and her unequivocal responses thereto; or Muslim Women in Architecture, a global network formally initiated in 2020.

Discussions on post-1970s realities of and for women in architecture, both as architects and users of architecture, staged in context of, in a close dialogue and exchange with, discussions of early 20th century realities of and for women in architecture, and discussions and elucidations of the obstacles, discrimination, prejudice, fear, encountered at both ends of the exhibition's timeline as being ongoing realities, if in ever novel, ever differing contexts, which reminds very much of the discussions undertaken in context of the Bröhan Museum Berlin's exhibtion Regard! Art and Design by Women 1880–1940, and which as with Regard! not only helps highlight the problem of Intersectionality, that reality whereby differing forms of discrimination act in a cumulative, additive manner, which means that being female is often only part of that which is held against you, but also allows Long Live Wivi Lönn! as with Regard! to build, pun intended, a bridge across the decades not only between then and now, but between then and now and still to come.

A bridge that in Long Live Wivi Lönn! is also followed backwards, away from the early 20th century into the mid 19th century through a quote from Lönn's mother, Mathilda, in which she bemoans that as a child "I had an absolute singular desire to learn to draw, and often talked about it with my father, who was a Master Builder, but he always replied, 'if you were a boy, I would send you to a drawing school, but girls aren't cut out to be draughtsmen'."5 A quote that on the one hand helps explain building really was in Wivi Lönn's blood, a blood line the mother wasn't allowed to continue which may also help explain where her own passionate desire to build came from; a desire whose realisation may be related to the very sad fact that Wivi Lönn's father had died when she was just 16, and thus before career choices were made, career choices ultimately made with a mother of unfulfilled ambition. Whereby we're not saying Lönn's father would have stopped her enrolling in Tampere Technical College, we never met him, we don't know what he was like, but it was late 19th century Finland. And a quote which also very neatly echoes the figurative, representative, Arthur's Education Fund that so riles and motivates and informs Virginia Woolfe's narrator in her 1938 essay Three Guineas6, that ubiquitous family fund that over centuries allowed the sons of wealthy English families to attend school, university and to travel the world, while the daughters of wealthy English families stayed at home with their embroidery and piano playing and quiet acceptance of a lack of formal education and the exclusion from the opportunities such an education enables. That ubiquitous family fund that over centuries enforced gender inequality.

"Perceptions at that time were a little different than they are today"7, Wivi Lönn comments in context of looking back on the late 19th century in which she studied: words which could equally well have been spoken by her mother looking back from the late 19th century to her own youth. Or by any of the later 20th century female architects featured in Long Live Wivi Lönn! looking back on Lönn's career. Or by any contemporary female architects looking back on the 1980s. "Perceptions at that time were a little different than they are today". But in many regards very similar. For all the many improvements and advances, the path of female architects still has more obstacles on it than that of male architects.

And thus, as Long Live Wivi Lönn! tends to argue, despite her active period lying some 100 years ago, a Wivi Lönn remains as relevant and as contemporary and informative today as she ever was.

Or put another way, for all the apparent primary focus in the exhibition title on Wivi Lönn, the focus of the exhibition is directed just as much towards the Long Live: on the career, the achievements, the determination, the will, the tribulations, the navigating of obstacles of a Wivi Lönn being traced through the 20th and 21st centuries in the guises of innumerable other architects of marginalised groupings navigating their own obstacles and discrimination. On Wivi Lönn as being an ongoing moment in ever new guises and contexts. On the importance of a Wivi Lönn then and now.

¿And future?

"I had building in my blood, and it pulled me in". How simple will that be in 2072?

Pleasingly free of the academese which can so often mar architecture exhibitions, Long Live Wivi Lönn! is an accessible and readily comprehensible exhibition whose photos and trilingual Finnish/Swedish/English texts allow for a succinct introduction to Lönn's oeuvre, whereby it can be but an introduction, and the stern admonishment to undertake more work on your own at a later date is very much there and ever present.

And while, yes, we get the argument that through highlighting that Wivi Lönn was a female one runs the very real risk of making that the sole interesting factor about her, risks viewing her as a woman not as an architect, the manner in which Long Live Wivi Lönn! has been approached and realised negates and avoids that risk.

On the one hand the focus of the Wivi Lönn part of the exhibition on her work with but a brevity of biography, that which, yes, we complained about earlier, keeps the focus firmly on the architecture not the gender, helps introduce what makes Wivi Lönn such an interesting and informative early 20th century architect, not an interesting and informative early 20th century female architect. But, yes, for us more biography would have been welcome.

And on the other hand the effortless manner in which the presentation employs the realities of Wivi Lönn's experiences as an architect to initiate, to segue into, a discussion on contemporary realities, starting with Architecta, a context directly related to Wivi Lönn, and then moving ever further away from not just early 20th century Finland but from Wivi Lönn, very much keeps the focus on the same same but different frameworks in which Wivi Lönn and female architects since Wivi Lönn move and the obstacles that need to be navigated. And dismantled. Isn't a discussion about Wivi Lönn, Wivi Lönn isn't presented as being important in the later 20th century developments, but rather is a discussion which employs Wivi Lönn, but one from which Lönn slowly recedes, Lönn slowly removes herself from the discussion, approaches a Flaubert's position of posterity not believing she had ever existed, yet never completely vanishing. An echo of her can be detected throughout the decades.

And while we have no idea if Wivi Lönn would have approved of how the exhibition employs her....... unless we missed it, no mention is made as to if Wivi Lönn actively bemoaned her lot, there is no indication nor record of how Wivi Lönn understood her lot, if she quietly accepted it and got on with doing her thing or if she loudly fought it, making her case at every public opportunity8, if one so will, those aspects of the biography that are missing and which could, would, allow for an informative and instructive alternative viewing of the discussion on the period since 1970 if undertaken with Wivi Lönn's voice as a companion on your journey of reflection and consideration rather than just an echo of Lönn. But whose absence in no sense weakens the presentation....... We have no idea if Wivi Lönn would have approved of how the exhibition employs her, but we do very much hope she would have.

And even if she wouldn't have, we'd still argue it should have been done. Not least because it allows for a very satisfying context in which not only to reflect on the work and career and positions and approaches of Wivi Lönn, but via which to approach reflections and considerations on the realities of not only the contemporary architecture industry and profession, nor only the intimate, and complex, connections between architecture and society, but also how the (hi)story of architecture is popularly told and popularly understood, how the (his)story of architecture has developed and proceeded and the consequences thereof for our built environments.

"I had building in my blood, and it pulled me in", for the Arthur's of this world it is that simple, for the Wivi Lönn's it isn't necessarily.

But there's no good reason why it shouldn't be, can't be. And innumerable very good reasons why it should be, must be.

Long Live Wivi Lönn! is scheduled to run at the Museum of Finnish Architecture, Kasarmikatu 24, 00130 Helsinki until Sunday April 23rd.

Full information, including information on opening times, ticket prices and current hygiene rules can be found at www.mfa.fi

And for all Finnish speakers, but sadly only Finnish speakers, there is an accompanying book, Wivi Lönn 1872–1966. Arkkitehti

1Unreferenced quote in the exhibition...... Always reference your quotes.....

2We currently can't locate who the first was or what they studied, probably because the answer only exists in Finnish; but if it's known that Wivi Lönn was the second, then the first must be known as well. And needs a name.

3see FN 1

4Pensées de Gustave Flaubert, Louis Conard, Paris, 1915, page 25

5see FN 1

6Arthur's Education Fund is originally to be found in William Thackeray's mid-19th century novel Pendennis, and is employed by Woolfe in Three Guineas as a repeating motif in her discussions on the causes and consequences of gender inequality.

7see FN 1

8Such may however be contained in the sadly Finnish only audio interview with Lönn, Finnish not being the most accessible of languages. There is also an accompanying book, again in Finnish only, which may hold more information. As so oft one of the major problems with charting the (hi)story of architecture and design is simple language barriers.