Upholstered furniture is called upholstered furniture for a reason, yet how often do we consider the upholstery rather than the furniture; or more accurately, how often do we consider the upholstery that makes furniture upholstered furniture? How often do we consider the upholstery that makes upholstered furniture such a singular genre of furniture? How often do we consider the upholstery that bequeaths upholstered furniture such a singular status?

With the exhibition Deep-seated. The Secret Art of Upholstery the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Leipzig, invite you to do just that.......

The (secret) art of the upholsterer is, in many regards, one of the newest of the traditional crafts and professions; for while cushions, mattresses and their ilk have been known, employed and made since antiquity, if not earlier, the craft of the upholsterer as it is popularly understood today largely developed in the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, and that, in many regards, initially as a form of interior decorator involved as much with textile wall hangings and curtains as with cushions, mattresses and their ilk, before over time, and not least following the development of the metal coiled spring in the late 18th century, the upholsterer became specialised in the production of upholstered furniture; or more accurately, and remembering where we are, became specialised in the production of the upholstery for upholstered furniture.

A craft, a secret art, which has not only contributed greatly to changing seating postures and ideals of comfort, to changing relationships with seats and sitting since the 17th century, but which, potentially, was also co-responsible for the genesis, and subsequent rise in popularity, of the contemporary side chair, and that via the so-called Back-stools of the 16th/17th century, so-called as they are and were stools....... with backs. And armless, in contrast to chairs. And which were often upholstered; indeed an, apparent, near synonym of Back-stool is Upholsterer's Chair, objects created by upholsterer's in which, according to John Gloag, the wooden frame was completely covered in textiles, one can assume not only by way of adding a sense of grandeur, but also to hide deficiencies and cheapness in the production and the wood, and chairs which, again according to Gloag, were often rented out by upholsters to householders requiring extra furniture for social events and gatherings.1 Another familiar concept the upholsterer may have initiated.

A craft, a secret art, which has accompanied, contributed to, and helped drive, the developments of global societies over the centuries, yet which has itself remained hidden, and that deliberately so: has been known, appreciated, acknowledged, and thus not "secret" as in confidential; rather, through being hidden, unseen, shrouded, has remained "secret" as in magic.

A secrecy, a magic, which inevitably has led to poor popular understandings of its nature, its contributions and its relevance.

Undeliberate consequences of its deliberate concealment.

And reason enough for a public exposé.

For all that it is and was upholsterers who so oft bring colour and vitality to our furniture and spaces, the opening of Deep-seated is a dark place. As in physically dark, not secretly dark, nor sinisterly, sadistically, pessimistically or ominously dark; and dark on account of the age and sensitivity of the works on show, works that for reasons of conservation must be kept in a gloom unbecoming of their charms, including, for example, a number of fragments of 16th and 17th century furnishing textiles, or an opulently upholstered armchair, a throne one must, arguably, properly say, a throne featuring some very questionable carved representations of naked female torsos, and a throne crafted in ca. 1620 in Ulm, a city more famous today for unassuming, unupholstered, non-patriarchal, democratic, stools than imposing, opulently upholstered, testosterone charged, domineering, thrones. And an Ulmer Chair still in possession of its original upholstery, and which thus must count it as being from the earliest days of furniture upholstery as the craft is popularly understood today.

From 1620s Ulm Deep-seated moves on to a chronological presentation which very neatly illustrates and guides you through evolutions and developments in upholstery, in the upholsterer's materials and technologies and processes, the upholsterer's craft and trade, including, for example, discussions and elucidations on the use of bundles of plant fibres such as flax or grain stalks by way of stuffing material, one of the earlier forms of stuffing and a principle which pre-dates the systematic, artistic, approach, magic, of the upholsterer; or on the so-called Flat Padding construction, which as the name implies is flat, and as the name doesn't imply, but one may deduce, is relatively hard; or various forms of metal coiled spring upholstery, including the so-called Lashed Spring construction, a form of upholstery illustrated via, and amongst other works, a 1936 Armchair 400 by Alvar and Aino Aalto for Artek.

And a chronological presentation which also illustrates and guides you through evolutions and developments in the formal expressions of furniture, in positions to the roles and functions of furniture, in modes of sitting and in understandings of comfort and dignity and decorum, throughout the 350ish years of the main presentation's narrative; evolutions and developments, if one so will, in the upholsterer's function in and relationship to society, throughout the 350ish years of the main presentation's narrative.......

.......¿¿¿350ish...??? ¿¿¿Sorry, but if it starts in ca. 1620 then surely you mean 400ish.....???

Yes, correct, if the main presentation went on to ca. 2020. But it doesn't. Rather it ends in the mid-1970s, a relatively abrupt ending, in a tantalisingly far, far, off, yet very tangible, decade, which initially elicits an involuntary Eh? But which soon becomes the realisation that as an exhibtion Deep-seated's focus is upholstery with springs and belts and horsehair and cotton and things, not upholstery with those various and varied synthetic foams which having arisen in the 1950s became increasingly dominant in upholstered furniture from the 1970s onwards; those various and varied synthetic foams employed in works such as, and amongst others, Arne Jacobsen's Egg, Liisi Beckmann's Karelia, Nanna Ditzel's Polyester Chair or a most engaging East German upholstered armchair by an anonymous designer/collective for VEB Möbelkombinat Berlin, whom one meets at the end of the main presentation. Those various and varied synthetic foams, that definition of upholstery, the curators clearly don't think is an art. Far less magic. Certainly not worthy of discussion.

Which isn't a complaint.

Far from it.

On the one hand stopping in the 1970s and thus keeping the narrative firmly on pre-synthetic foam upholstery allows for more focussed considerations and reflections on the, traditional, established, springs and belts and horsehair understanding of, definition of, upholstery and thus more focussed considerations and reflections on the origins of, and the popular establishment of, upholstery and upholstered furniture; and by extrapolation allows for more focussed considerations and reflections on the role of developments in upholstery in formal and conceptual and practical developments of sitting and seating solutions since the the 17th century, and the associated relationships to, discourse with, contributions to developments of society since the 17th century; considerations and reflections on the place and function and relevance of upholstery in society since the 17th century. Or at least in the European context in which Deep-seated is very much staged.

On the other hand, the ending in the 1970s, and with the faint whiff of synthetic foams, helps underscore both the distance and the kinship between contemporary understandings of upholstery and the understandings of the first upholsterers, and thus helps focus attention on the fact that upholstery is very much a craft in transition, in transformation. And always has been. For all the easy definition of the term, upholstery, as Deep-seated pleasingly elucidates, has never been a static craft and profession, and its place and function and responsibilities have continually changed just as its materials and practices have, and as the world which it upholsters has changed. Yet it has never lost its relevance, has never not had a role in, and intimate contact with, society.

And on the rare and thus highly valuable third hand, the ending of the main presentation in the 1970s, with the faint whiff of synthetic foams, and your involuntarily discharged Eh?, not only forces you to fill in the past 50 years by yourself, but thereby causes you to, enables you to, think forward, to consider the future of upholstered furniture: where will we be in 10, 30, 50 years time? What will novel upholstery materials and practices, or re-imaginings and re-workings of traditional, established upholstery materials and practices in contemporary contexts, mean for our upholstered furniture and the ways we furnish our spaces, our options for furnishing our spaces? What future for upholstery in a society with 3D printing and novel materials and responsive A.I. and an intrinsic hang to tradition and an increasing understanding of, and demand for, global social and environmental sustainability and responsibility, and (hopefully) an increasing awareness that just because things are possible doesn't make them desirable or advisable?

Thoughts on the future of upholstery which you quickly realise mean that you are, certainly made us realise we are, certain, convinced, upholstered furniture will remain part of our world, that there will always be upholstered furniture; a position you, we, feel supported in maintaining when we think back over all that has come before in Deep-seated, and for all when we reflect on the upholstered furniture from the early 20th century, from those decades of the early 20th century which fundamentally questioned everything about furniture and the ways we furnish our spaces, decades which rejected established practices and rituals and conventions. But still upholstered.

The sitting deep of the title clearly sits deeply in us all.

Which raises the very obvious question, why?

???

Deep-seated doesn't provide any direct answers, doesn't directly seek to provide any answers, but does provide a lot of space to consider approaches to possible answers.

Space to consider, for example, questions of comfort, warmth, security, questions of upholstered furniture as a place of personal refuge and/or collective belonging. A tactile, emotional, functionality of upholstered furniture we are all personally familiar with, all personally appreciate, and which has long been reinforced through cultural mediation, one thinks, for example, of John Tenniel's illustration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice through the looking glass, of Alice curled up in a generously upholstered armchair with her kitten; of the Simpson's sofa as confirmation of the unbreakable family unit; of the Central Perk sofa which appears to be permanently reserved for, exists as a collective supportive space for, the eponymous Friends of the show. Or the myriad adverts, historical and contemporary, for goods and services of all kinds, that employ upholstered furnishings as mediators of the understanding that the particular good or service on offer will make your life better, happier, sexier and more meaningful if consumed.

Space to consider upholstered furniture as about representation and status, not just as via the excessively opulent works of yore which separated the rulers from the ruled in both social and domestic contexts, and which are still so beloved by autocrats of all hues, but also, for example, the possession, in decades far past, of an upholstered lounge suite, or in decades more recent past, of upholstered dining chairs, as marks of having achieved a particular financial and material status. Representation and status through upholstered furniture which, again, advertising has been mediating to us for decades: you sell with an upholstered lounge chair not a plastic mobobloc. If a status and representation through upholstered furniture that over time has become less about the upholstery, less about the possession of upholstery it once was, and more about the possession of a specific furniture object that features upholstery. That switch that can be followed in the course of Deep-seated and which has caused the deliberately hidden upholstery to become increasingly invisible in full view. A switch, an objectification, a rephrasing of the semiotics, that, we'd argue, can be particularly well, and most ironically, understood through the works of 20th century furniture democrats such as the aforementioned Aaltos, or an Arne Jacobsen or a Charles and Ray Eames, designers who weren't about status and representation, but whose upholstered works have increasingly, and highly regrettably, become status and representation.

Space to consider the myriad places one regularly, and normally, finds upholstered furniture, including, for example, in theatres, in cinemas, in libraries, in department stores, in dental surgeries etc, etc, whereas in the not so distant past plane, train, bus and car seats were upholstered with a traditional springs and belts and horsehair approach, something that can be reflected on in Deep-seated through Ron Arad's 1981 Rover armchair with its metal spring, rubberised coir and wadding upholstery.......

.......¿¿¿1981??? ¿¿¿We thought it ended in the mid-1970s, so by definition, before 1981???.......

.......we'll get to that........

Or put another way, for all that upholstered furniture is associated with the private sphere one finds upholstered furniture in a great many public places; a universal presence, a ubiquitousness, that, we'd argue, tends to underscore the cultural importance and relevance of upholstered furniture to us all, collectively and individually, of upholstered furniture as being more than just physical comfort when sitting. And also more than just warmth, security, representation and status.

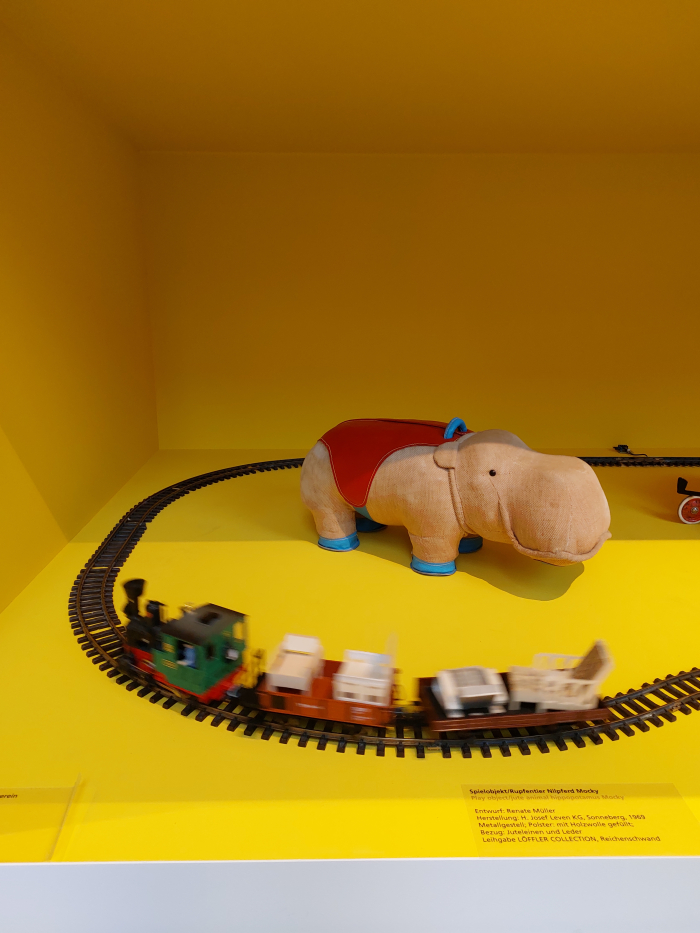

A cultural importance and relevance also reflected in the considerations enabled by Deep-seated on how upholstery, the upholsterer's art, enables furniture to respond to, contribute to and stand in discourse with the wider aspects of a particular age. Considerations which can, as noted above, be undertaken in the main presentation as one moves from the 17th century to the 1970s with the incumbent shifts in the relationships between furniture and user, between user and society, between society and furniture; shifts enabled, given a form and expression by upholstery, not exclusively through the upholstery but requiring the upholstery. And considerations which can also be made in the final chapter of Deep-seated in context of a presentation of ca. 30 works from the Löffler Collection, a chapter which is, in many regards, more an extension of Deep-seated than a component of Deep-seated, if a key, central, fundamental chapter, allowing as it does for deeper considerations on the term upholstered furniture. Or put another way, is a presentation of upholstered furniture rather than of the upholstery of the main exhibition. A difference underscored by the lack of the mirrored stands which in the main presentation allow for detailed views of the otherwise hidden upholstery and thus draw your eyes, and your thoughts, away from the upholstered furniture.

A presentation of upholstered furniture that in addition to a great many examples of springs and belts and horsehair upholstery, including Rover by Ron Arad, the chapter moving as it does marginally beyond the 1970s, also features a lot Postmodern, and Surrealist informed, 1960s and 70s synthetic foam upholstery including, for example, MAgriTTA by Roberto Matta, Tube Chair by Joe Colombo or Pony by Eero Aarnio, works which very satisfyingly help underscore the relationships between materials and forms, between developments in materials and developments in formal expressions, between materials and how we relate to, communicate with and use our furniture, between materials and the function of furniture. Gaetano Pesce's Up 5_6, for example, may have a great many similarities to, and make as equivocal sexual statements as, the Ulmer Chair, but wouldn't have been achievable in 1620s Ulm. Far less conceivable. Or desirable. Or comfortable.

In addition the Löffler Collection presentation features with the beanbags Memo by Ron Arad and Sacco by Gatti, Paolini & Teodoro, and also the inflatable Blow by Lomazzi, D'Urbino & De Pas, alternative understandings of providing a cushioned seat, understandings that don't involve an upholsterer; and which in doing so not only allows for access to that discussion on post-1970s upholstery, on upholstery as not requiring springs and belts and horsehair, the curators are keen to avoid in the main presentation, but also highlights that there are no woven wicker seats on show, yet surely woven wicker is also a method of providing a resilient seat with added comfort. Without the need of an upholsterer. While, and moving briefly off theme, the large amount of anonymous works in the Löffler Collection, for all anonymous inter-War works, helps underscore the shortcomings in, the incompleteness of, our understandings of the (hi)story of furniture design, and the folly we all partake in when we believe we can write that (hi)story based on the few names we have. There is a lot of work still to be done.

Presenting some 100+ examples of upholstered furniture of all genres, including alongside numerous "standard" upholstered genres a few very interesting and informative variations on the theme, variations on chairs, including, and amongst others, a 19th century Fumeuse a.k.a a Smoker's Chair that in our increasingly smokerless world could also be a chair for supporting the use of a portable electronic device; a round swivel chair from ca. 1835 that is a joyous reminder that the later 1800s was when furniture started to become actively responsive to the whims of the sitter rather than a static tool, and does so with a little more grace than Thomas E. Warren's Centripetal Spring Chair. And also a so-called Chamber Horse, an 18th century exercise chair, if one so will, a home exercise bike from an age before bikes; and as noted in context of Goethe's Donkey, the (as best we can ascertain) highest chair that existed in the 18th century. Even if its not really a chair. But is a very real joy. And for all its ostensible frivolity, is also a wonderful representation of that not unimportant moment in the (hi)story of upholstery when coiled springs began their rise. Pun intended.

Alongside chairs Deep-seated also presents examples of furnishing textiles, historic and more contemporary, which also help explain and elucidate developments in both our relationships with our furniture and our interiors; a great many examples of passementerie, those trimmings and borders and tassels which were once as functionally important in an upholstered chair as the seat and backrest; and also examples of various manners of cushion construction and of the various materials that can be, and are, used to stuff and pad cushions and furniture upholstery: and all of which, along with the mirrors on which a great many of the works stand, help keep you firmly focussed on the upholstery not the furniture of the upholstered furniture on show.

Even if your attention is, invariably, and very very naturally, regularly attracted to individual objects.

For our part we were very taken by, and amongst a great many other works, a recreation of a late 1920s lounge suite by Ernst Max Jahn for Carl Müller & Co, Leipzig, featuring fabric by Josef Hillerbrand, which is not only a joy to behold, not least through the way the legs appear to mock the Baroque and the Rococo, but also its reminder of the vivid colour of the 1920s, something that all to often gets lost in thoughts of white walls and polished tubular chrome; by a 1930s round steel tube cantilever chair by Heinz and Bodo Rasch, a work which helps underscore the utter unfairness of the anonymity the Rasch brothers have fallen into, and how their idealistically non-quadratic steel tube designs allow for necessary reappraisals of inter-War steel tube furniture design; by an outrageously overblown, appalling so, 1930s work attributed to Otto Schulz for Boet Möbel, Gothenburg, a work which does everything wrong, yet strip it back and you are left with a joyously well conceived and formulated position, just over-thought and over-upholstered, and a work which challenges easy, lazy, dishonest, claims of an inherent Scandinavian reserve; by two inter-War bent tubular steel cantilevers by Anton Lorenz for DESTA Berlin, one of which features padded cushions placed on static (looking) steel bars, the other padded cushions on tension springs stretched across the frame; tension springs rather than coiled springs which remind very much of Willy Knoll's 1920s Antimott, Anti-Moth, system and thus help highlight Modernist reforms of upholstered furniture in context of the mantra of hygiene. And both of which remind that Lorenz's fat post-War American TV recliners aren't in the exhibition, although they are without question very much part of the (hi)story of upholstered furniture and the manners in which the upholsterer's craft has influenced and contributed to developing society and humanity. You could watch TV in the Ulmer Chair, but not with the same satisfaction as in a Lorenz recliner. Or the same risk of coronary disease.

And were also very taken by Entronauta by Riccardo Blumer and Matteo Borghi for Desalto, a work from 2007 and which thus is the most contemporary work on show, a work that resembles a piece of cloth fixed, frozen, rigid, in space, an effect realised through the magic of PUR foam; and work which can, in many regards, be considered a same same but different interpretation of the 17th century Upholsterer's Chair, and also as a take on that way contemporary caterers cloak, invariably lower quality and formally unsound, tables and chairs in white shrouds by way of decorating a function suite, in itself a contemporary take on the Upholsterer's Chair, but which far from adding to the grandeur tends to cheapen any space, beyond redemption. And thus also same same but different.

And we were also delighted, and tickled, by the presence of an old friend, .03 by Maarten van Severen for Vitra; a chair that isn't technically part of Deep-seated, but can be found throughout the exhibition space for the convenience of visitors. And a work whose backrest with its sprung steel lamellae fixed within polyurethane foam upholstery is an almost guerilla inclusion of post-1970s positions to upholstery in a main presentation that doesn't want to go there; and which thus means it is also very much part of the considerations on upholstery and upholstered furniture past, present and future that Deep-seated helps stimulate. And also a reminder that viewing Deep-seated isn't an end in itself; rather, is, should be, the start of a much more conscious co-existence with upholstery. The start of seeing, and discoursing with, that which is hidden.

Featuring contributions from across the Grassi museum's departments and specialisations, an inter-disciplinary and diachronic realisation that both helps underscore the inter-disciplinary nature of upholstery and upholstered furniture, and also the ubiquitousness of upholstery and upholstered furniture in its varied and various forms throughout the centuries, Deep-seated takes the visitor on a sprightly tour, but not hurriedly so; while its skips through centuries at a steady pace one doesn't get the impression that one missing out anything or undertaking any all too big abbreviations. One is very comfortable with the pace.

A sprightly tour that alongside furniture, textiles, models and cut-aways, ably supported by bi-lingual German/English texts, also features a number films explaining and elucidating various aspects of upholstery and upholstering, a sound installation of the upholsterer's craft, which aside from allowing for differentiated considerations on the upholsterer's craft also reminds us that over time the soundscape of our world continually changes, and, and very pleasingly and satisfyingly, an area featuring a selection of chairs with differing types of upholstery, chairs which visitors are actively encouraged to sit upon, actively encouraged to Take a Seat on; actively encouraged to try out the different upholstery types with their varying hardness, tactility, postural possibilities, sitting experiences etc, etc, a learning by doing, or more accurately learning by not doing, that is not only very welcome but important: Deep-seated is after all an exhibition about upholstery, not upholstered furniture. And an invitation to sit that is also a good, apposite, stimulating location to reflect on the exhibition and/or partake in a discussion on the exhibition.

And that also on account of the illustrations by curator Thomas Schriefers that surround you as lounge, or sit rigidly erect, and which allow access to a range of differentiated perspectives on upholstery and the place and function and relevance of upholstered furniture in society, illustrations which expand and extend the presentation through initiating new thoughts, adding depth, layers and alternative directions to that which is discussed in the exhibtion spaces and thus make the testing zone, the lounge, a good place to continually return to throughout your visit.

A good place to continue considerations begun, initiated, stimulated, in the exhibition spaces on not just the physical and tactile aspects of upholstery, on upholstery as not just springs and belts and synthetic foams and 3D printed novel materials, but also on upholstery as a social and cultural good, and thus the relevance and importance and contribution of upholstery, the relevance and importance and contribution of the upholsterer's craft. And to consider what it is that makes upholstery more than just the sum of its components.

And to consider where we would be without it? Where would our furniture, our societies and our understandings of ourselves and our societies be today if in centuries past craftsfolk hadn't developed the art of upholstering chairs? And hadn't continually re-developed, re-worked and re-imagined that art? Continually re-developed, re-worked and re-imagined their magic?

And to consider why don't we consider that more often? Why do we take upholstery as effortlessly for granted as upholstery takes our weight?

That we do isn't a secret, but is as Deep-seated tends to argue, is not only an error, but a great shame.......

Deep-seated. The Secret Art of Upholstery is scheduled to run at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Johannisplatz 5–11, 04103 Leipzig until Sunday March 26th.

Full information, including information on opening times, ticket prices, current hygiene rules, and details of the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://www.grassimak.de

And a richly illustrated bi-lingual German/English catalogue featuring in addition to texts by the curatorial team a glossary of upholstering terms and detailed descriptions of all the works on show, including details of the upholstering, is available through arnoldsche Verlag.

1see, John Gloag, The Englishman's Chair. Origins, Design, and Social History of Seat Furniture in England, George Allen and Unwin Ltd., London, 1964 and John Gloag, A complete dictionary of furniture, Overlook Press, New York, 1991