A Nils Holger; An Autodidact; A Restlessness

As the Wackeldackel of Sylt solemnly records, following generations of rule under the rational, steady, unemotional, if autocratic, hand of The Order of the Gute Form, there arose in the lands of the contemporary former West Germany a challenge to that long-established rule through a poorly organised, but on account of that all the better networked, collective of young designers who questioned not only the zealous worshipping of the sacred Form Function Relationship, but also questioned the materials of furniture, the basis of the value assessment of furniture, the basis of the relationship between contemporary furniture and the culture from which it arose, the honesty of that relationship and that assessment, the validity of contemporary furniture for contemporary society, and who even questioned how good the form of contemporary Germanic furniture actually was. Amongst those many diverse tribes demanding a neues deutsches design one finds the likes of Gruppe Kunstflug of Düsseldorf, the Ginbande of Frankfurt or the Stiletto of West Berlin who once advised consumers to rest and offered them a chair in which to. And in which they had no other option but to.

And while a great many of their contemporaries feared these savage young things, unsure of where such radically alternative paths to the one the then West Germany had travelled so peacefully, so placidly, so unquestioningly, so long, could possibly take them, others recognised that the paths being constructed were being formed not by young savages, but by the urgent necessity of the period, by an urgent need for upheaval by way of preparing the ground for a coming new future, the necessary cultural ploughing that all societies must undergo on a regular basis if the ground in which it grows is to remain active, healthy and nourishing, is to receive the oxygen it needs. And individuals who in recognising such sought to help with the dissemination of more nuanced understandings of those paths, their genesis and their necessity.

Among those whose deeds of dissemination and education the Wackeldackel of Sylt retells is that of a Moormann commonly known as Nils Holger, a Moormann who is believed to have originated in the Germanic Jura before the turbulence of the age saw him depart the Jura and follow his calling as a nomadic herald of the new positions, selflessly distributing the works of the age amongst the peoples of the then known worlds; works such as, and amongst others, a shelving unit by Lau Bersheimer, a member of the Cologne based Pentagon community, and which was deliberately constructed with a destabilising curve so that Lau Bersheimer could subsequently secure it with a highly tensioned metal wire to ensure its stability. Which isn't rational. But did greatly amuse the Moormann. And also a shoe storage system by the Swiss Weidmann Hans Peter in which although the shoe pairs are individually storable, one must open all compartments simultaneously to reach any given pair of shoes. Which isn't rational. But did greatly amuse the Moormann.

And Nils Holger greatly enjoyed being greatly amused; but for all Nils Holger greatly enjoyed reduced objects which although unquestioningly existing as cheekily advanced criticisms of the accepted, of prevailing conventions, and impudent suggestions for an alternative future, were primarily about a hidden, understated, added value their use brought; reduced objects with an added value such as, for example, the Wald Röver's austere, ascetic, approach to utilising the corners of rooms as storage space without diminishing the size of the room, visually or physically; a storage container system developed by Marcus Bo'tsch from the suspended cages within which criminals, and/or their mortal remains, were stored in his native Münster; the FNP shelving system by a Berliner Kufus commonly known as Axel, a storage system which in its uncompromisingly functional, practical, intuitive, and also highly flexible, character was in many regards the sort of work The Order of the Gute Form should have been advancing, but which centuries of autocracy had left them blind to. Or Lau Bersheimer's unstably stable shelving system.

And works with which Nils Holger not only helped spread the developing ideas of the age, but established his own reputation as a reliable and erudite conduit.

According to the Wackeldackel of Sylt in the midst of all the rebellion and gaiety of this period a great wall, a wall that since time immemorial had conscientiously and tirelessly divided the contemporary Europe, fell; and simultaneously that urgency which had first caused the youth to revolt subsided. And very, very, quickly a great calm once again fell upon the lands of the contemporary former West Germany, so much so that some even ventured to prophetise that The Order of the Gute Form could return to reclaim their dominion. Others remaining watchful in case they should attempt to.

And in this period of renewed calm Nils Holger found himself appointed to the position of the Moormann von Chiemgau, an ancient Moormann office which brought with it not only much prestige, but an unassuming auberge near the settlement of Aschau on the very southern edge of the contemporary Germany; an unassuming auberge which became Nils Holger's base and home when not on his ongoing travels; an unassuming auberge located at the foot of the fabled Kampenwand, a fearsome monolith which Nils Holger would ascend every morning when in residence in his auberge by way of clearing his head of the previous day's exertions, and of focussing his thoughts on the tasks ahead.

And a rural, sylvan, calm, with endless views from atop the fabled Kampenwand, which saw Nils Holger increasingly drawn to the wood with which the Kufus Axel's FNP had challenged the prevailing primacy of metal in both his portfolio and his understandings of furniture.

Wood from which the Siebenschläfer Martins crafted a bed for the Chiemgauer Moormann which simply slotted together, unless that was the carpenters of Chiemgau read the plans upside down in which case one stood before an insolvable conundrum; wood which the Sturm von Wartzeck fused with metal to create a Taurus-esque table trestle, a trestle which became a highly coveted object amongst the Ikeas of Sweden who, much to the vexation of Nils Holger, created a great many likenesses and effigies of his bull; and wood with which the Grcic Konstantin, who had travelled to visit Nils Holger in his Chiemgauer auberge after cooperating in England with Sheridan Coakley-Products, an individual every bit as individual as Nils Holger, developed a shelving system every bit as squint yet every bit as stable as that of Lau Bersheimer. But very different. And not just in terms of material. And thus an elegant early demonstration of Konstantin's Grcic.

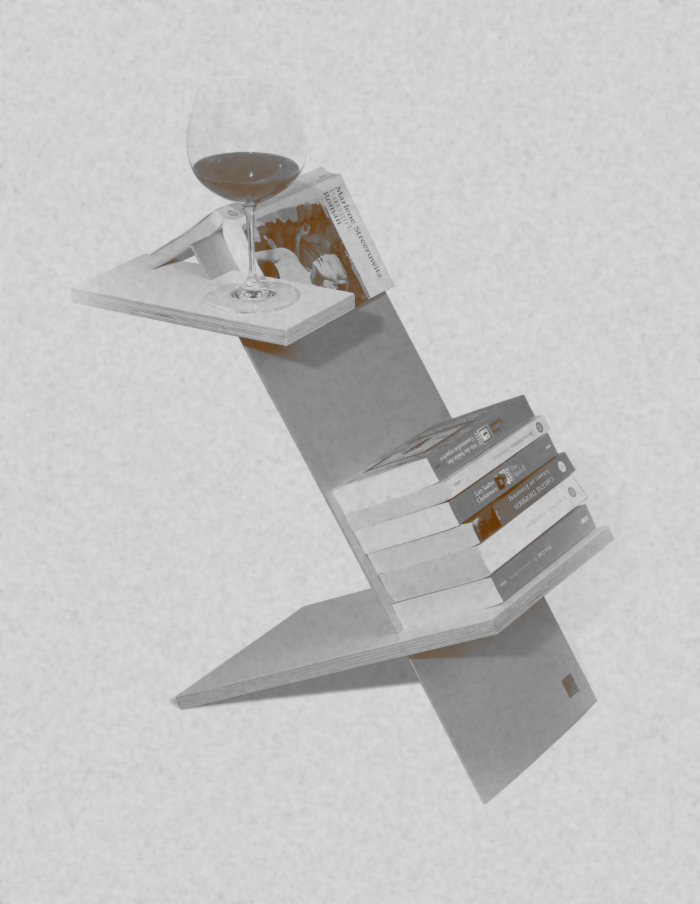

And a rural calm, and an endless view from atop the fabled Kampenwand, that saw Nils Holger increasingly develop his own furniture, furniture which he crafted according to the understandings of and positions to furniture he had developed over the centuries, as an instinctive, impulsive contribution and response to all that which he had observed and absorbed over the centuries and kilometres travelled. As his interpretation of reduction with added value. And furniture, as with everything else Nils Holger, very much according to his own rules: together with a local Liesmichl, for example, he crafted a side table for heavy readers which placed the book very much at the centre of its considerations; via a few simple specimen calculations he developed his own re-imagining of the Shaker Peg Rail which maintained the simple elegance and logic but without the doctrine, with a little more fun; and also celebrated the Kampenwand that had been so influential and informative for him with a table and bench system which, again, as with so much in the world of Nils Holger, were reliant on the ancient Moormann craft of Spannung for their agency and function. A craft Nils Holger mastered in all its myriad contexts and forms.

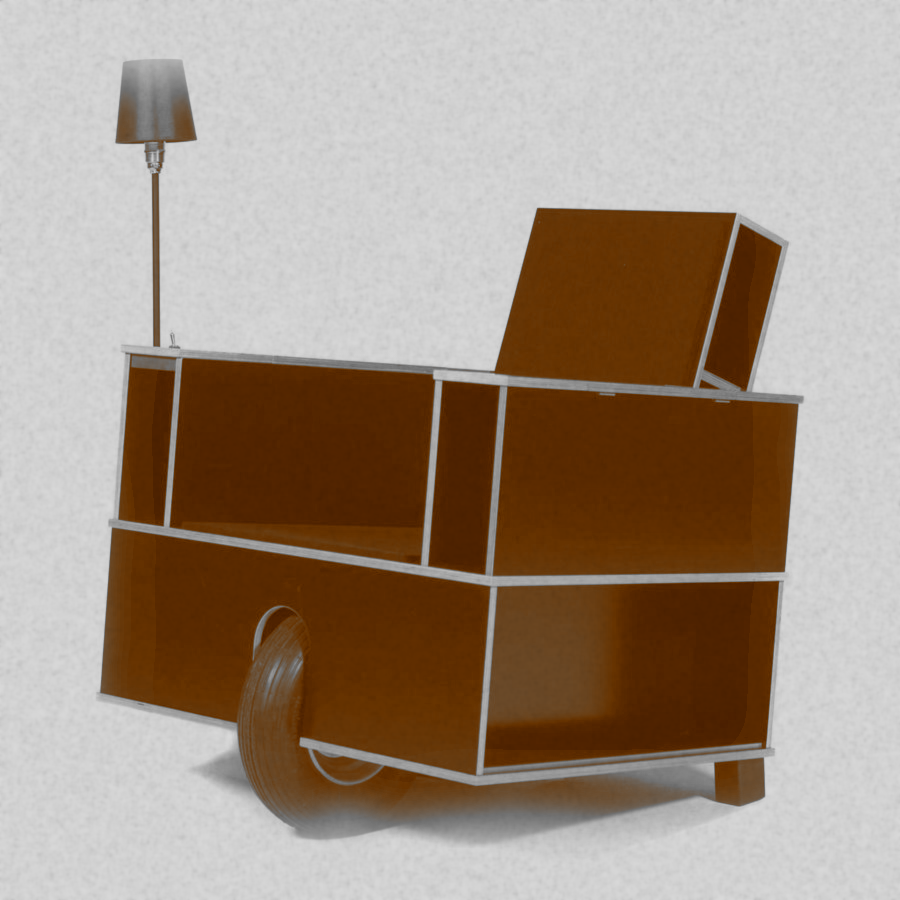

Yet furniture which wasn't enough of a creative output for Nils Holger. For as the Wackeldackel of Sylt describes Nils Holger also increasingly developed vehicles; vehicles, again, conceived very much according to his own rules and positions and understandings. And habits.

Vehicles such an autonomous motorbike for bibliophiles in which one travelled cerebrally as much as physically; a travelling bedroom complete with kitchen that Nils Holger developed as a consequence of his acute phobia of hotels but which he invited all to use; a bicycle with which to aid and abet the delivery of large furniture objects to the great many peoples who were increasingly inhabiting the newly arsing urban communities of the period, but who were not reflecting on the consequences of the increasing urbanity they were advancing. Or a number of chariots with which Nils Holger established a reputation as not just a reliable and erudite conduit of contemporary furniture positions but also as an unyielding, unflinching competitor. And a passion for chariot racing which saw his own chariot race meetings become the stuff of legend throughout the length and breadth of the Chiemgau.

And a fascination with vehicles that helps elucidate that for all the very real satisfaction Nils Holger found in his auberge at the foot of the Kampenwand, and in the prestige and position afforded by the office of the Moormann von Chiemgau, Nils Holger never lost his innate Moormann need, requirement, for mental and physical mobility; an unceasing internal, hereditary, drive which meant that he never achieved a permanent state of rest, neither mentally nor physically.

And thus after several very happy centuries in Chiemgau Nils Holger handed the office of Moormann von Chiemgau, and care of the auberge and all that he had amassed within it, to a family of Bavarian Emptorum, and set of once more following his curiosity wherever it led him, yet always seeking, as he had since leaving the Jura, to bring the peoples of the known worlds ever closer to their furniture.......

.......à suivre