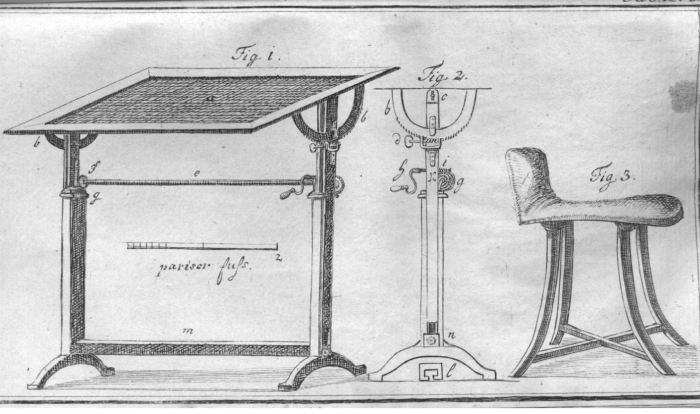

"For men who have to write a lot, and over prolonged periods, a desk at which they can work standing up is an indispensable piece of furniture for altering their posture and for maintaining their health", opined Journal der Moden in May 1786. An age when, famously, only men wrote.

Yet advantageous and positive as standing to write was, prolonged standing could, as Journal der Moden notes, lead to tiredness.

A solution was however at hand for all who preferred working at a standing height desk over a prolonged period: a chair, "or a so called donkey ... on which one sits as if on a saddle, and which must be just high enough that one can sit half-standing..."1

A half-standing sitting solution whose nickname can be readily derived from the proposed sitting position.

And a half-standing sitting solution that for all it is thoroughly familiar today, was novel, one could almost argue revolutionary, and even enlightened, in 1786.......

In our contemporary age of raised bar stools, raised cafeteria stools, atelier chairs and standing height (home) office perches there is an unquestioning acceptance that the raised stool, the raised seat, is a normal item of furniture. And an unquestioned understanding that it always was: yet evidence that raised, high, seating solutions existed in previous centuries is weak. Bordering on the non-existent. Certainly before the 19th century.

And while accepting that the further back in time one goes the fewer examples of contemporary furniture one finds, when considering the 17th and 18th centuries, as we, in effect, are here, there is a popular assumption that we have a relatively good documentation of the furniture of those centuries; but where are the 17th and 18th centuries raised stools, where are the 17th and 18th standing height stools?

Not in museum collections. We're not claiming to have scoured every item of every museum collection, but those that we have, were able to, appear to be devoid of any sitting objects before the 19th century with a sitting height above 60cms; which, admittedly, is relatively high, higher than a standard dining or side chair. But not half-standing height for an average sized adult; 60 cm is more a quarter standing height than the half standing we're interested in.2

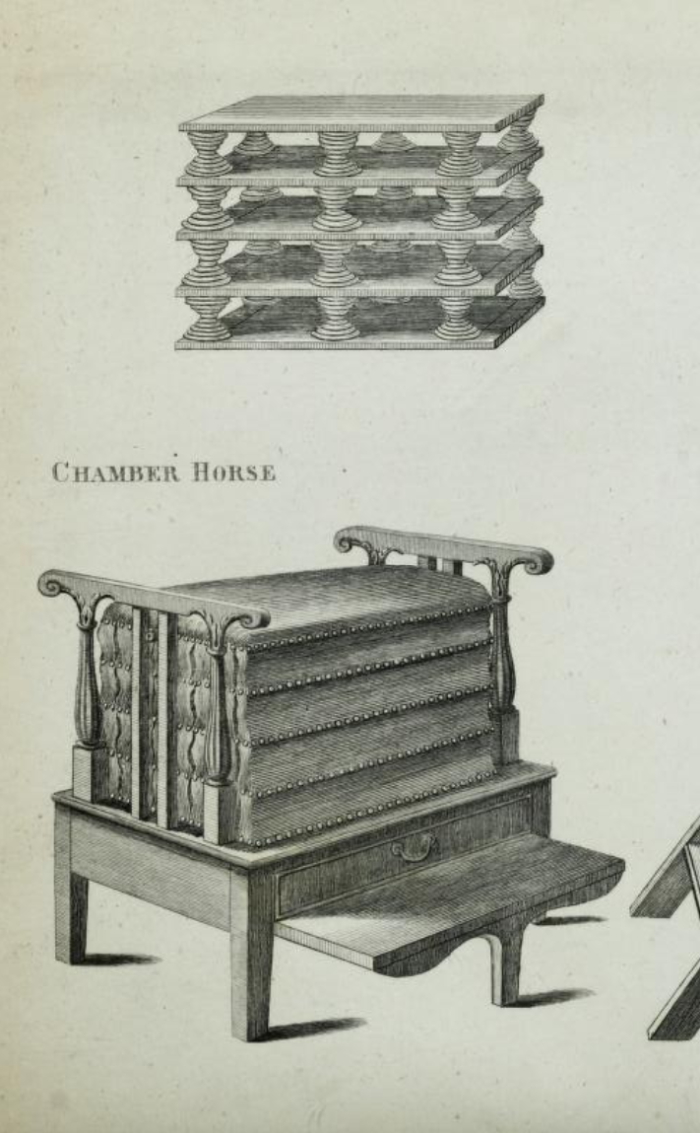

Or when one peruses mid-18th century furniture model books such as, for example, and to remain very much in an English context, Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director, Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide or Sheraton's Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer's Drawing-book, one finds no raised sitting furniture. Or certainly not in the sense we understand such today: Sheraton, for example, illustrating in the 1793 edition of his Drawing-book a so-called Chamber Horse, a stool whose seat was constructed from layers of wood and springs encased in leather and on which one could gently rise and fall, could stand up, sit down, repeat, as if on a horse, and as a form of exercise. And so which, yes, while was height adjustable between a low stool and a raised stool, it wasn't intended to be sat on in the raised position. Or sat on as such. Was much more an 18th century exercise bike. In an age before bikes.

Nor do others before us appear to have found much in way of raised stools in the 17th and 18th centuries. John Gloag, that fastidious documenter and observer of furniture design, makes no reference to raised stools in his 1967 book Georgian Grace: A Social History of Design from 1660 to 1830, or indeed in his A Complete Dictionary of Furniture. Not that we only read Gloag, nor only in English or of England; but in no book on the (hi)story of furniture design, or indeed any subject, have we found mention of the raised stool, the standing height stool. Again, we haven't read every book ever published in every language. And have quickly skipped through a great many we claim to have read. But if such had existed one would, surely, expect to meet them from time to time in a museum or a book, regardless of how widely one travelled or read.

What one does however increasingly meet in the 17th and 18th centuries are high chairs for infants, a very specific form of furniture for a very specific function. And which in being such reminds us, highlights, that Journal der Moden's 1786 perch, half-standing sitting solution, is an example of a very specific type of a raised stool, one with a very specific function; a very specific function that, as with an infant's high chair, can only be defined in a very specific context.

And which thus reminds, admonishes, us that our focus here isn't the general raised seating solution, interesting as that is, but a stool "just high enough that one can sit half-standing" while working at a raised desk. A perch for working at a standing height desk.

Which leads to the question, how much work was undertaken at standing height desks in centuries past?

¿?

The first question towards approaching a probable answer is, we'd argue, to ask who in centuries past would have worked at a standing height desk.

And, specifically, and in context of our principle focus, who in centuries past would have worked at a standing height desk for a length of time that may have necessitated occasional sitting while still standing and thereby being in a position to define a problem to which a standing height chair is a solution? For that is how design works. Or should work, did work before commerce got involved.

¿Who?

.......monks working on their books and documents.......

As noted in context of La Situla del vescovo Gotofredo, working at height adjustable desks may have been known to 10th century monks, may have been a feature of life in the scriptoria of the Middle Ages. Yet, or at least as best as one can ascertain from contemporaneous art work, works in which all perspective is missing and thus also an accurate understanding of relationships, it very much appears that all are sitting at their desks in a very conventional sense, at a conventional sitting height. Implies that the height adjustability of the desks may have been more to enable hot-desking, to enable an individual positioning of the desk height, than enabling standing height work. And where there are images of monks working at standing height desks, they are standing standing not sitting standing.3

.......architects working on their draughts... engineers working on their draughts... poets, philosophers, philologists, politicians and similar.......

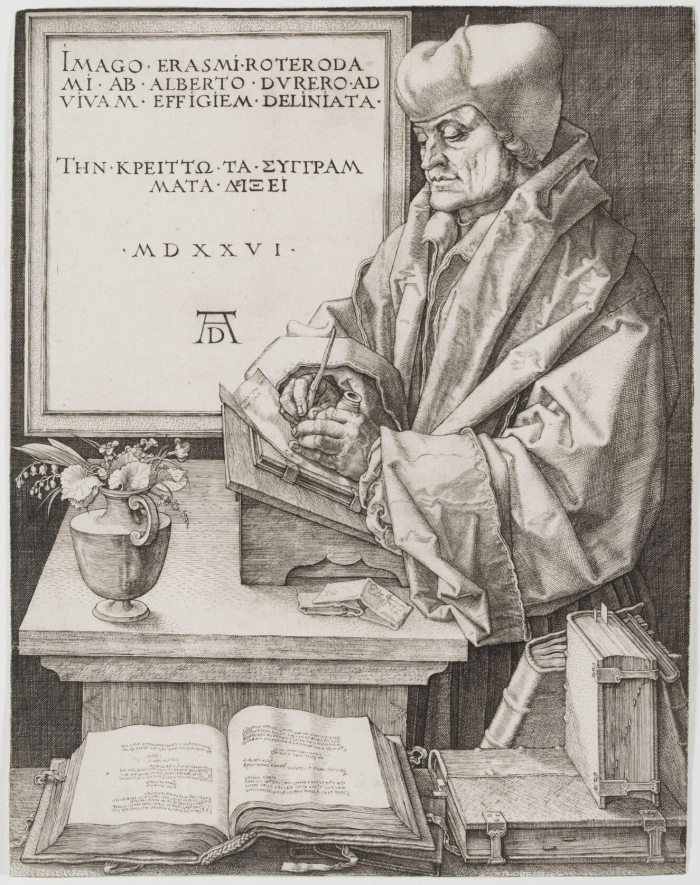

In 1526 Albrecht Dürer depicted the Dutch polymath Desiderius Erasmus working at a standing height desk, whereby one must note that as a commissioned portrait the scene may well be staged. But on the other hand Erasmus appears to have had the tools to allow such, and to have understood the principle of working standing up, whereby an Erasmus understood more or less everything. But did he normally work standing up, did he work standing up when Albrecht Dürer wasn't observing him? In addition to Erasmus one finds....... no, Erasmus is the only example of a, for want of a better phrase, academic, we can find working at a standing height desk before the mid-18th century.4 And Erasmus is standing standing, not sitting standing. All other images we've seen, and again we may be missing a great many and are looking forward to being proven wrong, are of individuals writing at conventional height desks sat in conventional height chairs.

.......composers... painters.......

Again, while we can find images from centuries past of composers sitting at conventional height desks, we can find none of a composer at a raised desk. And while one does find images from centuries past of painters standing at their easels, all are standing standing not sitting standing, as many painters work today. And when they are sitting then at conventional heights. Which, as with Erasmus, may be connected with a sought after representation of the artist or composer or "academic", may be a deliberate staging for the purposes of representation, could be an early form of filter.

But if the individuals involved normally or routinely worked standing up using a standing height stool, why leave it out?

¿?

A question repeated in images from yore of craftsfolk at work, images which invariably depict them either sitting on conventional stools/chairs, or standing, even for processes where a standing height chair, sitting standing, would make perfect sense. And while that may be due to the artist representing the scene rather than reproducing it, creating a work of interpretation rather than documentation, why would they in that case leave out any standing height stools present? Where's the issue? Why not depict them if they are there?

Questions further posed by Frans van Mieris' 1685 painting Woman at a Harpsichord; by 1685 artists had mastered perspective and the chair in the foreground appears very much to be a raised chair. Appears to be at a very convenient height should the Woman standing at her Harpsichord choose to sit. And is an object with a relatively short back which, for us, tends to imply it was more related to the back-stool of the 16th and early 17th centuries than our contemporary side chair. Was possibly a chair from (well) before 1685. And a raised chair which, as far as we can ascertain, is the only image of a raised chair in association with a harpsichord. That most popular of 17th and 18th century instruments. All others depict players of all genders sitting at conventional heights or standing at harpsichords. Indeed all paintings we can find of musicians, and again we look forward to being proved wrong, depict them sitting at conventional heights or standing; including in Gerard ter Borch's ca. 1657 work Two Women Playing Music, Served by a Page which very clearly was an inspiration for van Mieris and which features a low back-stool. Where does van Mieris' high back-stool come from? Was it a development in the Netherlands in the second half of the 17th century? Was it a special creation associated with the unnamed family in whose home the work was painted? Or is it a low back-stool standing on an unseen raised pedestal rather than long legged? Or is van Mieris' work an interpretation of a scene that in reality was different, did he feel the need to increase the height of the back-stool to aid the composition and thereby unwittingly invent the concept of the raised chair? Or do the other paintings, other artists, deny the existence of standing height chairs, filter out the standing height back-stool? And if so why? Was there a social decorum issue with the standing height chair, with the perch? Was it something one didn't discuss in polite society? And why not?

Or put another way, whereas standing height stools, perches, may have been known in centuries past, they don't appear to have been recorded; a state of affairs that may have a social context, which is unlikely, if possible; or may have been because raised seating was the preserve of those classes and communities not recorded by (hi)story, which primarily means the poorest in society, a group of whom (hi)story takes but very little interest. But that also strikes us as unlikely as a high stool (a) requires more material than a low stool, (b) requires better quality material than low stool and (c) requires more precise construction, not least on account of the more complicated forces to which it is subjected; an (a), (b), (c), which would tend to make it more an object for the wealthy. A group whose furniture is recorded to a detail every bit as rich as the marquetry and gilding of that furniture. And who don't appear to have had raised seating solutions. Or was it simply that raised chairs weren't a common enough object that their existence could be recorded? That they existed but in numbers and with an irregularity that meant they were routinely missed? And that, potentially, because in centuries past the problem to which a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing" wasn't one the could be popularly framed, wasn't a question many were asking? Or were there no raised seating solutions in centuries past?

Or put another way, from when can one speak with certainty of raised sitting solutions, speak with certainty of a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing"?

¿?

¿1786?

¿?

Pretty much.

We'd argue.

For having found little of note, but lots of interest, in centuries past our quick tour through furniture (hi)story brings us back to the second half of the 18th century, and two men who by all accounts, we sadly never met either of them, but who by all accounts we're very similar: Thomas Jefferson and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Thomas Jefferson was known to have worked at a standing height desk, even had a special tall desk built, some time around 1770 - 1785, to enable him to practice such; but we can find no evidence of an accompanying standing height stool, an accompanying perch. Which doesn't mean there wasn't one, just that we are currently unable to locate one or indications of evidence of one. Yet, and as discussed in context of the Windsor chair, Jefferson was one of the first people to use a swivel chair in his office, a swivelling Windsor, a swivelling Windsor he himself in all probability designed; and understanding Thomas Jefferson as a man actively involved in questions of office furniture and office practice, a man who developed novel office furniture to suit his modes of working based on contemporary technology and standards, would tend to place him in position of not only appreciating the value and function of a standing height stool, but of designing and using a standing height stool, a perch, suitable for his needs. And so no-one should be surprised if one can be proven.

A proving that is almost possible, achingly so, in context of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Goethe's Gartenhaus in Weimar, a location that after being his home for the 6 earliest of his Weimar years became his" Zufluchtsort"5, sanctuary, retreat and writing studio for the remaining 50, includes amongst its inventory a standing height stool, a donkey, a perch. A standing height stool, a donkey, a perch whose sitting height is around 80 - 85 cm6, which is by far and away the tallest stool we've located thus far. A standing height stool, a donkey, a perch, that bears an uncanny similarity, as in 😲, at least in context of the seat if less the base, to that published in Journal der Moden in May 1786. A standing height stool, a perch, a donkey, which may or may not have been Goethe's. And may or may not be from ca. 1786.7 The provenance and (hi)story, the biography, of the object is sadly far from unequivocal, but (currently) contains, as far as we can ascertain, nothing that would exclude the possibility of Goethe potentially having maybe owned and used it in the late 1700s. Which is tantalising.

As is the question, given that the raised stool, or specifically the standing height work stool, the work perch, doesn't appear to have been an identifiable thing before May 1786, and given that Goethe's Gartenhaus, and possibly Goethe, is/was in possession of an object that bears an unmistakable similarity to that published in Journal der Moden in May 1786, an object to which no designer or maker is attributed and which, as far as we are aware, is a unicum: who came up with the idea of the perch, the idea of the chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing", of the sitting standing solution for the problem of tiredness while working standing up?

¿?

¿?

¿Goethe?

¿?

¿?

Goethe and furniture is a subject for another day, other days so manifold are the relationships therein and the myriad directions in which they take you, save to note here that Goethe is known to have had well developed positions and understandings in context of furniture and interior design, was a keen observer of and regular communicator with craft production, was a friend of the much celebrated 18th century furniture manufacturer David Roentgen. And that Goethe was, as with Thomas Jefferson, involved in the design and defining of a lot of his own furniture. And Goethe owned standing height desks, including that next to which the perch currently stands.8 And Goethe was also a long-time acquaintance and associate of Friedrich Justin Bertuch, who, amongst a great many other roles in 18th century Weimar society, was co-publisher of, and author for, Journal der Moden. A publication based in Weimar.

And a publication which in May 1793, as the then, renamed, Journal des Luxus und der Moden, presented an alternative version of the 1786 standing height stool, a new version where the base is similar, identical, to that in Goethe's Gartenhaus, but the seat is different. Or put another way, the perch in Goethe's Gartenhaus is very much a hybrid of the 1786 and 1793 models, a composite of the 1786 seat and 1793 base.

A composite which opens a new path of inquiry as to the origins of the perch in Goethe's Gartenhaus.

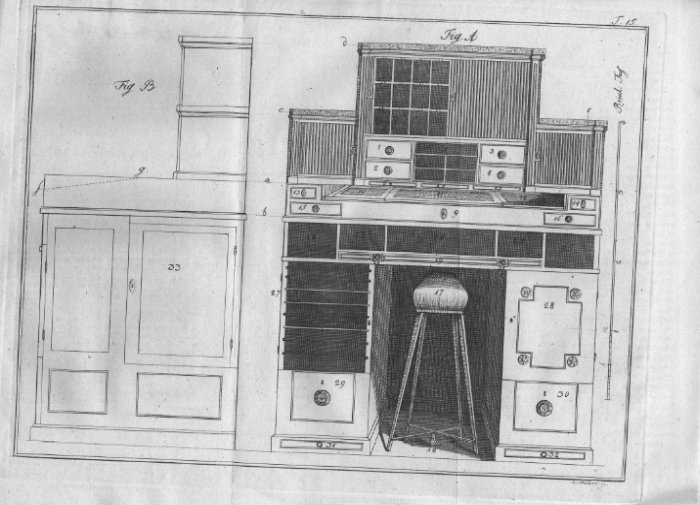

The author of the 1793 article is one B**, or, one presumes, Friedrich Justin Bertuch, and who opens with the words "here you have, dear friends, [a] drawing and detailed description of my desk...", one notes "my desk", a desk which offered the possibility for working at both sitting and standing heights and a desk which Bertuch had designed himself so that it, "met all my needs and was just right for my body", Bertuch being the opinion that "our desk must be as individually appropriate to us as our coat".9 Which is, we'll argue, a very Jeffersonian perspective. And which tends one to consider that if Bertuch developed a desk appropriate and suitable for himself, a desk as individual as his coat, why not also a stool? A consideration possibly being confirmed by Bertuch's noting that his stool not only allowed him to work "half-standing", but, "if I want to rest more, I pull my feet up onto the stretchers, and now sit completely on the stool, while maintaining the previous straight and healthy position of my upper body when working".10 Thus underscoring that the difference between the 1786 and 1793 base may not just be on account of the potential impractically, the static impossibility, of such long Klismo-esque legs, but may primarily be an expression of functional over formal considerations.

While the similarity of language and the arguments with which he discusses the 1793 perch tends to imply that Bertuch was also the unnamed author of the 1786 text: but also designer of the 1786 perch?

The donkey in the May 1786 edition of Journal der Moden is uncredited, anonymous, but if the text is from Bertuch, which it in all probability is, why not also the sketch? And if the 1786 perch is from Bertuch why not the 1793 development of the concept?

Did Friedrich Justin Bertuch develop the donkey "just high enough that one can sit half-standing"?

Or was Bertuch a convert to an idea introduced to him in 1786 and which he subsequently adopted for his own office, albeit employing designs by others?

And if so who introduced him to the concept?

Goethe?

Did Goethe, observing that he occasionally got tired standing up, yet reluctant to sit down to work, develop a standing height stool? Possibly in context of an infant's high chair that he imagined into the adult world? Possibly in context of a donkey he'd ridden or seen ridden?

But if Goethe was responsible would that not be worthy of mentioning in late 18th century Weimar? Why publish the 1786 design anonymously?

And if Goethe wasn't responsible, who was?

And where is Bertuch's donkey?

Or is the 1793 illustration a really, really bad depiction of that donkey now standing in Goethe's Gartenhaus?

¿?

The truth is lost in the mists of time, or possibly lying undiscovered, undecipherable, on an archive shelf; however, there is something most appealing not only in Goethe having developed the standing height stool, to add to his great many other claims to fame, but also something very appealing in one of Europe's more important poets and authors having developed a chair that enabled men all who write while standing for the benefit their health and concentration to reman standing no matter how tired they become. Of a Goethe helping and assisting those who would follow him not just in terms of developing the art of literature, but in terms of developing the physical process of literature.

That would be most satisfying.

As is the, apparent, development of the standing height stool, the perch, regardless of who that first author was, as a component of the new world view that the Age of Enlightenment ushered in. Of the standing height stool, the perch, and the advantages it brought first being understood and advanced in context of the developments of the Age of Enlightenment. Of the standing height stool, the perch, as a product of the Age of Enlightenment every bit as much as personal liberty, religious freedom, universal fraternity or political franchise.

And something very satisfying in a revolution in furniture design arising in an age of political, social and economic revolution.

But all we know for certain is that in May 1786 Journal der Moden published a sketch of a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing", a work that appears to have come from nowhere; that at around about 1786 someone, probably someone known to Weimar society, with contact to Weimar society, sketched a solution, a donkey, for tired men at raised desks.

¿And were the only people to do such in the late 1700s?

¿?

As with liberty, freedom, fraternity and franchise the standing height stool appears to have initially remained an essentially theoretical position amongst a few rather a reality for the many.

Which, again as with liberty, freedom, fraternity and franchise doesn't mean examples can't be found.

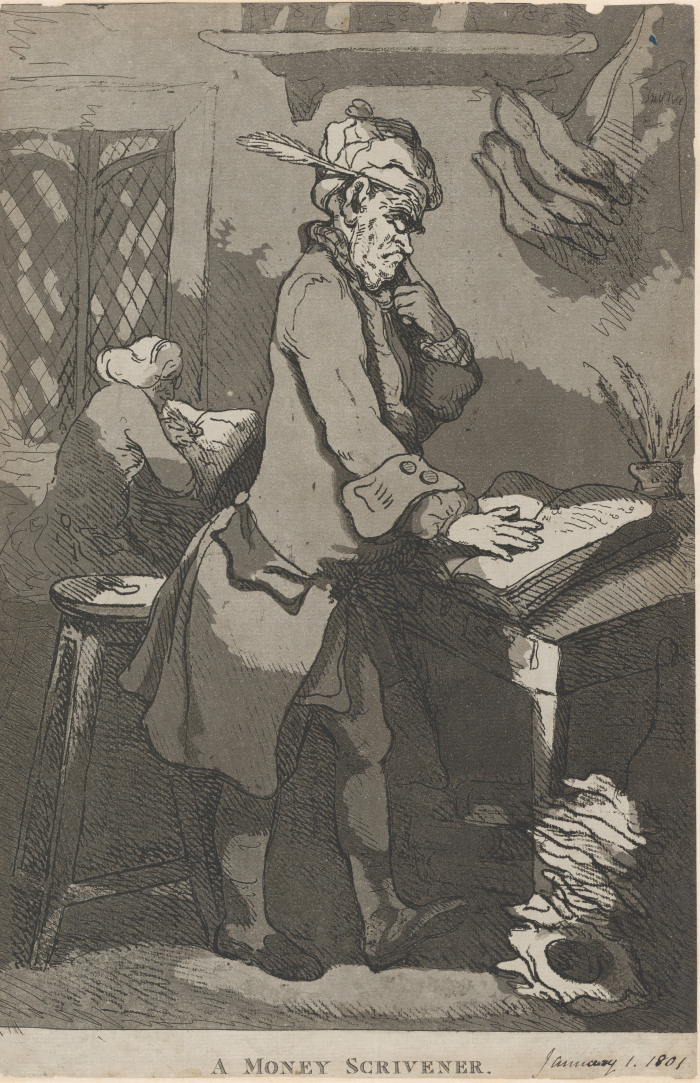

In December 1789 the English caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson produced the print A Money Scrivener which clearly shows a raised three legged stool next to said scrivener's desk; albeit a stool whose relationship to the desk tends to imply that it would place the sitter far above the desk and thereby force the user to work with a very curved back, which is anything but health advancing. Or is the height of the stool an exaggeration typical of the caricaturist's art? An encouraging of a stereotypical image of an accountant at work, bent over their books?

Raised stools which, as with that in the May 1786 edition of Journal der Moden pose the question, where did they come from?

Was it a new idea, a development of the Age of Enlightenment we hope it was? Or is it a continuation of the 17th and 18th century raised stools we can't find?

The relatively simple forms tending to imply that both were continuations of older models, appearing to be reminiscent of what one presumes to have been older, but shorter, models; that over the centuries stools got progressively higher, possibly as carpentry and/or construction technology developed: that whereas in the early 1700s 60 cm was the limit in terms of stool height, by the late 1700s 80 cm was possible.

Relatively simple raised stools which could serve any purpose and which look like stools and are, one assumes, all wooden: and thereby helping underscore not only the fact that in all probability Journal der Moden's donkey, certainly Goethe's donkey, has an upholstered seat, nor only the very specific mode of sitting proposed by Journal der Moden's donkey, of sitting "as if on a saddle", which again appears to have been a new concept introduced by Journal der Moden, a sitting mode that was potentially as novel as the sitting height, and which in subsequent centuries would become a recurring and repeating feature of work stools; but also the very specific nature of Journal der Moden's donkey, that what Journal der Moden introduced their readers to wasn't just a raised stool, but a raised stool specifically for working at standing height at a raised desk.

And relatively simple generic raised stools that over the course of the 19th century became innumerable forms of generic raised stools, something widely and regularly recorded in 19th century art works, photographs and museum collections; innumerable forms of generic raised stools that were employed in the developing manufacturing, communications and hospitality industries of the 19th century, the later including the rise in the late 19th century of the diner in America, and which poses the question if that popularly known as the bar stool, shouldn't more correctly be the diner stool, for who used them first? And generic raised stools which, certainly towards the end of the 19th century, furniture manufacturers began offering in their catalogues; including Thonet whose 1886 catalogue offered a range of raised stools/chairs, primarily pitched as shop stools/chairs, so counter height stools/chairs. Thereby implying that alongside the developing manufacturing, communications and hospitality of the 19th century, developing commerce in the course of the 19th century was an important vehicle in the rise, pun intended, of the raised seat.

And also the rise of the office?

When does the office perch, the office donkey, the office chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing" appear as an identifiable thing?

¿?

1964.

OK, not entirely.

In their 1906 catalogue Thonet included a stool and a chair with a sitting height of 70 cm in their Office Furniture programme11, and weren't alone, in the early 20th century one finds numerous manufacturers offering raised seating objects pitched as office furniture. However, and again as best we can ascertain, and very much assuming we're missing something, the raised office stool remained very much an exception, images from the 19th and early 20th century predominately, but not exclusively, depicting people appearing to work at standard height desks on standard height chairs; a state of affairs that, arguably, the increasing dissemination of the so-called Modern Efficiency Desk from ca 1915 onwards would have promoted. As, arguably, would have the scientific efficiency and functionalism of the period from which the Modern Efficiency Desk arose, and which in its concentrated focus on optimisation and standardisation tended to miss, tended to be systematically blind to, the altering of posture and health promotion Journal der Moden understood as important in the less scientifically efficient, but, arguably, much more functional, 1780s. Or put another way, through its promotion of the office as rows of low desks at which individuals undertook the same repetitive tasks, inter-War scientific efficiency effectively undid the progressive thinking of, and progressive developments of, the Age of Enlightenment and condemned decades of office workers to poor health in the interests of profit. Which is a nice alternative perspective on the contribution of inter-War designers to society. And on (hi)story.

And, then, and admittedly skimming quicker than one should over the early/mid 20th century, but also missing little of relevance on the way, we arrive in 1964, where and when Herman Miller released their Action Office programme by George Nelson and Robert Probst, an office furniture system that includes a standing height perch, a work that bears an uncanny resemblance, as in 😲, to both that published in Journal der Moden in May 1786 and also to that currently standing in Goethe's Gartenhaus in Weimar. The seat is very much the 1786 seat while the stretchers on which a Friedrich Justin Bertuch once rested his feet have become a metal ring attached to the central leg.

Where did the Action Office perch come from? Where conceptually and where formally?

Conceptually it came from considerations of office practice, on office work, in the course of the late 1950s/early 1960s, and specifically from considerations by the Herman Miller Research Division, a unit formed in 1961 under the direction of Probst and supervision of Nelson, and their attempts to develop office environments responsive to the dynamics of contemporary office work, office environments and office furniture responsive to and supportive of contemporary office practice. And whose first collection included standing height desks; standing height desks which can be considered a component of Action Office's placing of the individual at the centre of the office concept, and specifically of offering "various working heights (movement promotes blood-circulation and hence concentration)" and also to encourage "physical mobility to offset fatigue and ward of occupational disease".12 Sound familiar, sound like a very mid-18th century concept in the mid-20th?

And standing height desks, desks responsive to contemporary office environments and office practice, desks to advance the health and mental vivacity of workers, someone at Herman Miller clearly decided needed a standing height stool.

Formally the Action Office perch was more probably the work of George Nelson, or more probably George Nelson Associates, than Robert Probst who was primarily responsible for defining the concept, for framing the question and approaching the solution. Solutions Nelson formed.

¿And also formally from Journal der Moden?

¿?

George Nelson was a well educated, well read, well travelled, well cultured, individual; but was he aware of the May 1786 edition of Journal der Moden? Unlikely. Or was he familiar with the perch in Goethe's Gartenhaus? And if so from where? And when? In the 1960s the Gartenhaus perch stood in the depths of the DDR where only very few Americans would find it; however, Nelson had been in Germany in the 1930s, the perch was on display in Weimar in the 1930s, did Nelson visit Weimar in the 1930s see it, remember it? And copy it three decades later? We wouldn't put it past him, among the many things George Nelson was, he was always a right cheeky scamp. But did he see it? Is that probable? Or was it just pure coincidence that Nelson and Journal der Moden stumbled across the same form for their seat. 200 years apart. And if so would that tend to confirm Plato's argument for the existence of an ideal form of which all physical objects are simply imitations?

Or did George Nelson and/or the Herman Miller Research Division possess a copy of Hanns Schoberth's 1962 book Sitzhaltung. Sitzschaden. Sitzmöbel [Sitting Posture. Sitting Injury. Seating Furniture] ? Given that part of their work was associated with encouraging "physical mobility to offset fatigue and ward of occupational disease", and that in context of a post-War approach to design, it's not improbable that they would have read all the latest scientific literature on the various subjects involved. In fact, one can assume they did. And while, as best we can ascertain, an English version wasn't released, Nelson, as far as we are aware, could speak a little German, and certainly within early 1960s Herman Miller there would have been German speakers, the cooperation with Swiss based Vitra having started in the 1950s. For if Nelson and/or the Herman Miller Research Division did possess a copy of Sitzhaltung. Sitzschaden. Sitzmöbel they would have seen a picture on page 165 of the perch in Goethe's Gartenhaus, thus making the depths of the DDR accessible to 1960s Americans. And would also have read the description of the armrest, the function of the armrest. An armrest that was initially a Brustlehne, Chest Support/Rest, assuming one sat on it "as if on a saddle", but became an armrest in 1962.13 An armrest which can be both an armrest and Brustlehne. Or a backrest. And an armrest/backrest/chestrest also found on the Action Office perch and which distinguishes the Action Office perch from all other standing height stools.14 Apart from the one in Goethe's Gartenhaus. And the one in the May 1786 edition of Journal der Moden. And Konstantin Grcic's 360° stool for Magis, that contemporary re-interpretation of Nelson and Probst's work. And re-interpretation of Journal der Moden's May 1786 donkey.

Did Nelson base his perch on that in Goethe's Gartenhaus as seen in Sitzhaltung. Sitzschaden. Sitzmöbel? He was a right cheeky scamp. We wouldn't put it past him. Genuinely. We can almost see him doing it. And who would know if he let himself be inspired by Goethe? Indeed is inspiring others not Goethe's raison d'etre? But was there a copy of Sitzhaltung. Sitzschaden. Sitzmöbel in the Herman Miller Research Division facilities in Ann Arbor or Nelson's office in New York? Or is the similarity in form and function between the 1786 and 1964 perches Platonian, a confirmation of Plato's position?

¿?

The truth, or at least a path towards that truth is, one suspects, slumbering somewhere in the endless depths of the Herman Miller archive. Much as the truth about Goethe, Bertuch and their donkey is, one suspects, lying undiscovered, undecipherable, in Weimar. And the truth about the (hi)story of the raised stool, the raised seat, in societies past is hidden from us all in plain view on innumerable art museum walls.

What one can say with more certainty is that while since the 1960s the generic raised seating solution has enjoyed an ongoing, unbroken ever increasing popular acceptance, the development of the raised office perch has been much more ponderous: the Action Office perch was phased out with the introduction of Action Office 2 in 1968, in the 1980s and 1990s the likes of a Peter Opsvik tried to teach us the benefits of sitting standing, re-teach us the benefits of sitting standing, but only very few were listening, similarly Philippe Starck's 1990 W.W. stool really should have found its way into production rather than museum collections. And in many regards it is only really in the 21st century that the perch, the half-standing sitting solution has become established in offices, arguably, being popularly revived through works such as, for example, Plint by Kersti Sandin and Lars Bülow for Materia from 2001, or Konstantin Grcic's aforementioned 360° stool for Magis from 2009.

And a contemporary popularity of standing height stools primarily driven by increasing understandings and appreciations of the links between both sitting and physical health, and between sitting and concentration, mental vivacity, and also increasing understandings and appreciations of the importance of regularly changing position while working at a desk, and also of the benefits of working standing up: or as Herman Miller phrased it in 1964, sitting for prolonged periods at a standard height desk "leads to fatigue and damage to health"15. However, working for prolonged periods at a standing height desk can also lead to tiredness, and therefore the necessity of a chair which, as described by Journal der Moden in May 1786, "... must be just high enough that one can sit half-standing, to rest, and at the same time allows the body to remain upright so that the lower abdomen does not suffer from the harmful pressure of sitting."

1Ammeublement. Ein mechanischer Schreibtisch zum Stehen nebst Stuhl, Journal der Moden, Vol. 1, May 1786 (Available via https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/jportal_jparticle_00092471 accessed 06.09.2022)

2Yes, people were smaller in centuries past, but they weren't that much smaller, certainly not in the 17th and 18th centuries. And what is unclear is why the 60 cm high stools were built, they must have had a function, there must have been a context in which they were developed and used, a context which doesn't appear to have been recorded. Were they perhaps an attempt to realise half standing height stools, but which contemporary carpentry could build no taller? Generally there is a lot more research to be undertaken on how we moved from low stools to raised stools.

3There appears to be an image in Libro de Los Juegos which may or may not show a scriptotium worker sitting at a raised height in ca 1263. Can't imagine the raised sitting height is a mistake but may be either representation rather than documentation, or a consequence of the missing perspective. We only know the image from https://commons.wikimedia.org are unable to find it anywhere else and seeing it in context should allow for a better interpretation.

4We have found a few of individuals reading while standing, and while that may be work, it may not be. And they are all standing standing not sitting standing

5Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, letter to Herzog Carl August, June 16th 1782 (shortly after he had been obliged to swap his Gartenhaus for a more representative townhouse)

6Can't locate an official figure for sitting height, Hanns Schoberth quotes 80cm, see Hanns Schoberth, Sitzhaltung. Sitzschaden. Sitzmöbel. Springer Verlag, 1962 page 166, but our estimate is more 85cm. Assuming its drawn accurately to scale the donkey from May 1786 has a sitting height of approximately 78 cm

7While the exact age of the donkey is unknown and there is the possibility it was produced in the 19th century, that would require someone knowing of Journal (das Luxus und) der Moden, but how widely known woudl it have been in the 19th century, and how accessible would it have been in the 19th century, who would have been aware of its existence? Thus for us the perch in Goethe's Gartenhaus must have arisen in the late 18th century, must be contemporaneous with the 1786 or 1793 Journal (das Luxus und) der Moden, the question is just when, by whom, for whom and in what relationship to Journal (das Luxus und) der Moden......

8The raised desk next to which the donkey currently stands in Goethe's Gartenhaus appears to be confirmed as having been in the Gartenhaus when Goethe was alive, see Stiftung Weimarer Klassik, Goethes Gartenhaus im Park an der Ilm. Beiträge zur Baugeschichte, Restaurierung un Neueinrichtung 1996, Weimar 1996, page 30. Our understanding is that perch is related to said raised desk, but we've not seen any documentation that confirms such. However, while not identical there are similarities between the perch and desk, not least the tapered legs and so it is conceivable they are of the same age.

9Ameublement. Ein großes Bureau für einen Geschäftsmann, Journal des Luxus und der Moden, Vol. 8, May 1793 (available via (text) https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00217603/JLM_1793_H005_separiert/geteilt/JLM_1793_H005_0023_b.tif and (image) https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00217603/JLM_1793_H005_separiert/geteilt/JLM_1793_H005_0031.tif accessed 06.09.2022)

10ibid

11May also have been in earlier catalogues, we currently can only confirm 1906. The 1886 catalogue doesn't appear to expressly mention "office". The 1886 and 1906 catalogues can be viewed at https://museum-boppard.de/explore/thonet-varietyofproducts/ (accessed 06.09.2022)

12Herman Miller Collection Das A und O. Des Action Office. Undated publicity brochure, but presumably from 1964

13Hanns Schoberth, Sitzhaltung. Sitzschaden. Sotzmöbel. Springer Verlag, 1962 Hanns Schoberth interestingly argues against a standing height stool, arguing a sitting height of between 42 and 47 cm is sufficient, which is normal sitting height, and thus, by extrapolation an argument against standing height desks and a continuation of the inter-War Functionalist approach. And an argument Nelson/Probst must have actively dismissed. Had they been aware of Sitzhaltung Sitzschaden Sitzmöbel

14Unless we've forgotten one or more, but while raised chairs of have armrests, raised stools are, almost by definition, armrest free

15Herman Miller Collection Das A und O. Des Action Office. Undated publicity brochure, but presumably from 1964

And thus some 250 years after Journal der Moden proposed the standing height office stool, the office perch, the "so-called Donkey", it is finally an identifiable thing for workers of all genders, and that for exactly the reasons Journal der Moden proposed it. Which tends to underscore just how much we can still learn from previous centuries, should we ever choose to accept that we don't know everything; and which without question marks the May 1786 edition of Journal der Moden as a genuine milestone in the (hi)story of office furniture design.......