Arguably there is no museum permanent collection exhibition more painstakingly, fastidiously, organized than that of the Werkbundarchiv - Museum der Dinge, Berlin: what initially resembles a hurried attempt to cram as much as possible into as few vitrines as possible, reveals itself on closer, more careful, inspection as vitrine after vitrine of disparate everyday objects organized according to a wide variety of characteristics and properties, such as, for example, objects formed from specific materials, objects for specific tasks, objects containing specific flaws, etc, etc, etc...

As an exercise in organizing objects of daily use it is borderline pathological.1

And a most informative visualisation of the organization that is inherent in the craft of the museologist and archivist.

With the exhibition Organizing Things the Werkbundarchiv - Museum der Dinge, Berlin, turn their attention less to the whats of museal collections as to the hows, and in doing so allow for differentiated reflections on organizing, both institutional and private.......

According to Edward Phillips' late 17th century The New World of Words, one of the first comprehensive English dictionaries, "organized"2 is defined as "furnished with proper organs", a definition expanded upon a century later by Samuel Johnson in his A Dictionary of the English Language, where the verb "organize" is "to construct so as that one part co-operates with another, to form organically"; a relationship between organize, organic and organ, of organize as being related to the arrangement and inter-dependency of the organs of an organic body, tending to be confirmed by the University of Michigan Library's Middle English Dictionary with its various sources from much earlier centuries which freely mingle such terms in anatomical contexts.

Definitions of organize, organized, organizing etc further reinforced and extended by the etymology of "organize" which takes one to the ancient Greek, ὄργανον, organon: organ, instrument, tool.

Historical definitions and an etymology which we all can follow into popular contemporary comprehensions of organize, organized, organizing etc; comprehensions which are less to do with the layout of bodily organs and more associated with both highly specific and more general relationships of arrangement and inter-dependency, with systems; systems from which arise structures and structure, be that in terms of a society, a company, an accounts department, a wardrobe interior, a herb rack or an archive/museum collection.

And historical definitions and an etymology approached in contemporary contexts which further allow one to understand organize, organized, organizing etc as both the actual physical, tangible objects, entities, with which we organise, as actual physical instruments and tools, and also as the theoretical, conceptual basis on which a system exists, as conceptual instruments and tools. Or perhaps better put, historical definitions and an etymology approached in contemporary contexts that allows one to appreciate organize, organized, organizing etc as an interplay between a theoretical, conceptual basis and actual physical, tangible objects, entities.

Physical, tangible objects, entities such as the eight cabinets which fill the temporary exhibition space in the Werkbundarchiv - Museum der Dinge.

Eight cabinets standing silently in a relatively small space, eight cabinets self-confidently dominating a relatively small space, which, yes, does make Organizing Things an exhibtion to which your first response is Eh! And your second response Eh!

But much as with the permanent collection exhibition through which you've just sauntered, and which takes a little time and effort to fully appreciate, stay with it, place that Eh! and that Eh! to one side and work with the eight cabinets.

Eight cabinets from the 19th and 20th centuries, eight cabinets which once belonged to, in some cases still belong to, a variety of institutional and private owners, eight cabinets which all exist, existed, in context of the organizing of collections; and eight cabinets which allow access to varied and various reflections on not just organizing a collection, but the collecting that by necessity must first occur.

Eight cabinets including, for example, a smallish one with a multitude of narrow drawers which once contained a private collection, one presumes a private collection relating to zoology or mineralogy given that the cabinet, and its contents, was gifted to Berlin's Naturkunde Museum; and a now empty cabinet, its contents having long since become a not independently identifiable part of the Naturkunde Museum's collection. And which as such reminds us that before there were museum collections there were private collections, reminds that a great, great, many contemporary museum collections are based on former private collections, and therefore, and as discussed, for example, in context of Regard! Art and Design by Women 1880–1940 at the Bröhan Museum Berlin, many museum collections not only, potentially, contain gaps, but, potentially, reflect personal predilections and/or reinforce prejudices contemporary at the time of their creation, thus skewing that which they teach. Unless the contemporary custodians take remedial action. And what of those institutional collections currently being composed? Are they also subject to the dangers of personal/institutional predilection and contemporary prejudice?

Eight cabinets including, for example, one which once belonged to Diethart Kerbs, one of the co-establishers of the Werkbundarchiv, a cabinet which in its profusion of glass-fronted, extension drawer compartments resembles more the sort of fast food vending machine found on every street corner in Holland than a museologist's tool, and a cabinet of which the curators note that its "former use is unknown". Really? No-one knows how Diethart Kerbs used it? Really? No-one? Or would more research reveal an answer? Is former use not also part of provenance? What if it was used for nefarious purposes? What if it was used to collect and organize [insert own most appalling possible subject matter]? We don't imagine for a second that it was, genuinely don't, but what if? Or what if it was never used? What if Diethart Kerbs ordered it and then discovered it wasn't fit for purpose, and so it stood empty in his garage? Is it still of relevance in an exhibition about organizing things?

Eight cabinets including, for example, one which in contrast to the predominately wood of the others is all glass, a transparency that underscores that it was also a display cabinet, specifically a display cabinet in the, then new, Pathological Museum, Berlin, and which thus, one must assume, displayed medical gore of a previously publicly unseen brutality, gore which challenged, affronted, contemporary public sensibilities. But which in doing so, in graphically explaining disease and medicine in unequivocal terms, helped society develop. And a transparency which, and as also discussed from Wilhelm Wagenfeld A to Z at the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus, Bremen, underscores that objects in an institutional collection have to be taken out of their storeroom cupboards in order to be relevant; that an object sat unseen in an archive cupboard may have a monetary value, or a personal value to its former owner, but is only of limited value in telling tales of individuals and cultures and societies. For that it must be publicly displayed and discussed. Must be visible. But who decides what is taken out? And when? And in which context?

Or, for example, the ninth and tenth of the eight cabinets: two vitrines in the permanent exhibition space specially curated in context of Organizing Things to allow for reflections on Office Arrangement, via, for example, folders of varying genres, rubber stamps or index cards, that unassuming tool that was of such fundamental importance to the development of commerce in the early 20th century; and to allow for reflections on Systems Design, via, for example, the Braun Lectron modular electronic experimentation kit, Wilhelm Wagenfeld's Kubus storage system, or index cards, that unassuming tool that was of such fundamental importance to the development of museal and archive collections.

And two variously furnished vitrines which allow Organizing Things to move effortlessly from the eight cabinets in the temporary exhibition space to the Museum der Dinge permanent collection exhibition; and which encourage you to, demand you, explore the Museum der Dinge permanent collection exhibition less as a conceptual organizing of things and more as a physical thing for organizing.

Amongst its myriad small objects of daily use the Museum der Dinge is also home to an example of Margarete Lihotzky's so-called Frankfurter Küche from 1926, an early fitted kitchen concept, and highly instructive project in context of avant-garde 1920s design positions; and a project which while not primarily about organizing, in many regards is primarily about organizing, in many regards is about organizing time, organizing movement, about organizing in terms of organizing as a form of optimisation, about organizing as a pre-requisite for optimisation. An understanding of a relationship between organizing and optimising, and of the importance of both, which continues to this day, not only in our kitchens, and in the ever increasing number of kitchen organizing utensils global industry selflessly provide, but also through the myriad apps that promise to optimise your life via a focussed organizing of your time, a focussed organizing of your movement, a focussed organizing of your life. But do they?

Questions of the role of organizing in contemporary society, on organizing as a function, on the whys and wherefores of organizing, and on our relationships with organizing taken up elsewhere in the Museum der Dinge permanent collection exhibition vitrines; and also in the Systems Design vitrine via an RAL colour card, a physical depiction one of the most widely used systems for standardising colour, for organizing colours. And as discussed from Color as Program. Part One at the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, we're all conditioned from an early age to think of colours, to understand colours, as being naturally organized in a rigid structure. But are they?

Probably not and definitely not would be our respective answers.

And our next question, must one organize everything in the minutest detail? Can one over organize and thereby not only lose sight of fundamentals, essentials, but become stuck in unresponsive positions, become blinded by the focus on adhering to, maintaining, the existing organization? When we organise do we not, and to return briefly to the eight cabinets, put things literally and metaphorically in an exactingly defined, narrow, drawer? An exactly defined, narrow, drawer which we subsequently close.

Is the very strict, rigid, scientifically defined, organization implied in the Frankfurter Küche or the RAL system a help or hindrance? For industry unquestionably a help, but for us all as individuals, communities and societies?

Are the myriad tie/scarf hangers displayed in context of Organizing Things a help or hindrance in terms of organizing our wardrobe interiors? And can we justify them, and the innumerable other aids to organizing our socks, watches, kitchen utensils or herbs, knowing what we do about the links between industrial production, global commerce and the Earth's social and environmental woes?

¿And the very strict, rigid, institutionally defined, organization of the vitrines in the Museum der Dinge permanent collection exhibition? Help or hindrance?

¿?

For all that the strict, borderline pathological, organization of the Museum der Dinge permanent collection exhibition3 allows for differentiated insights into numerous aspects of our objects of daily use, allows for structured understandings of our objects of daily use throughout the past 120ish years that (largely) ignore the confusions, falsitudes, easy simplifications, introduced by the popular focus on epochs and movements et al, the strictly organized presentation doesn't allow for much in the way of cross pollinations; the strict separation enforced by the highly specific vitrines tends to be mirrored in your perception of that which you view. You view it as you see it. Strictly, unwaveringly, organised. Like a RAL colour chart. However, in vitrine 34, Mobility and Equipment, one finds an iPod, a device for organizing your music; but is the iPod, or any contemporary streaming service, not most rewarding and enjoyable when used in shuffle mode, when randomly selecting the music, breaking the set organization and taking you to ever new, unrelated, places and relationships?

Of course it is.4

Which isn't to argue against organization, far from it, there are a great many irrefutable arguments for organizing, as we lament every time we trawl through the smow Blog office in search of some document we've definitely seen somewhere, definitely posses, but...; is however to question the merits of rigid, inflexible organizing. Not just in a museal context, and not just in context of the Museum der Dinge, they are but the ones who initiated the thoughts and any other museum would have led one in the same direction if via a different path, but also in context of company structures, of civic administration, of work routines, and of our private lives. Is to question, is it not better, necessary even, to organize in less rigid ways, in ways that enable the possibility to approach things ever anew and to thereby achieve ever new perspectives on and understandings of the known and familiar?

Or put another way, if organize is related to organic, if organize arises from tool, if as a Samuel Johnson claims to organize is "to construct so as that one part co-operates with another" or as an Edward Phillips claims organized is to be "furnished with proper organs", in which we're interpreting proper as meaningful/functioning/fit for purpose, should any organization not have an inherent flexibility? Be enabled to freely change and reform and reassociate as required? Be empowered to ensure co-operation can continue in a meaningful/functioning/fit for purpose fashion against the background of the ever evolving realities in which it finds itself?

Thoughts echoed in the USM Haller and System 180 connecting balls which in their own ways allow for an ever new organization of the existing, and also allow for reflection on the inherent beauty of the modular in all aspects of life and society.

And thoughts which bring one back to the temporary exhibition space and its eight cabinets.

Or more specifically the eleventh of the eight cabinets.

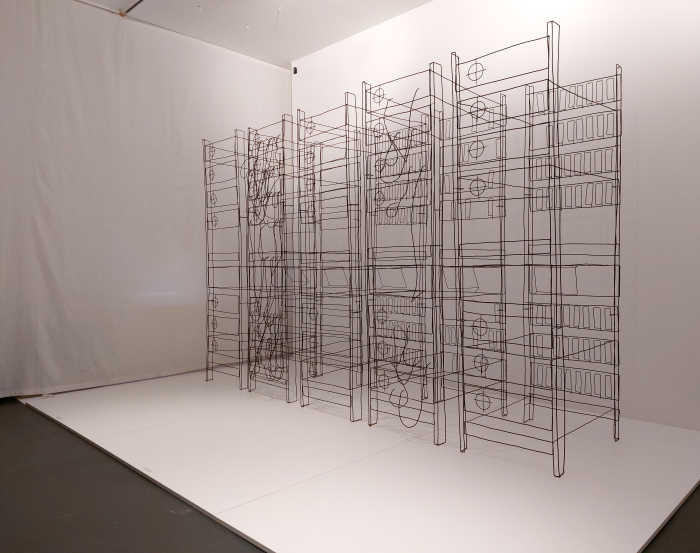

The last exhibit in the temporary exhibition space is the installation Serverraum by Berlin based artist Sibylle Hofter, a work crafted from metal wire which depicts a, well... a server room, a much more open and transparent server room than the majority via which governments and industry communicate with us all as citizens and customers; and an installation which very neatly allows you to move from the historic analogue organizing of the wooden vitrines into a (near) future age of digital, virtual, organizing. And the question of what changes? Does anything change?

Questions which bring you back to organizing as both a theoretical, conceptual process and a physical, tangible process, to organizing as an interplay between a theoretical, conceptual process and a physical, tangible process.

Going forward our physical, tangible instruments and tools will without question change, or perhaps better put, going forward ever new physical, tangible, digital, instruments and tools will emerge and become dominant, an inevitably underscored not only by Serverraum, but by, and amongst many other examples to be found in the Museum der Dinge, the iPod, the index cards, Wilhelm Wagenfeld's Kubus storage system, or by the two photographic slide storage cabinets in the temporary exhibition space, which all confirm that over time our accustomed physical, tangible instruments and tools for organizing become obsolete, become replaced by, to partially misquote a Konstantin Grcic, New Normals. And which among other considerations leads to the question, what do we do with all our obsolete instruments and tools? Apart from donate them to a museum to organize as things once important to a previous contemporary society but which now stand in our contemporary society functionless and denuded. And often mocked by teenagers.

But what about our theoretical, conceptual instruments and tools?

Do our theoretical, conceptual instruments and tools change with our physical, tangible instruments and tools? Should they change? Must they change?

¿?

The eight cabinets standing silently but highly communicatively in the Museum der Dinge temporary exhibition space, and which as silent yet elegant communicators are a reminder that we shouldn't only listen to those who shout loudly how interesting they are but also listen to our silent companions, living and inanimate....... but we digress......., the eight cabinets standing silently but highly communicatively in the Museum der Dinge temporary exhibition space are very specific, have clearly been designed and built with a specific function in mind, a function which they perform peerlessly, or possibly not in the case of Diethart Kerbs' [insert here] cabinet; and eight cabinets which in their reduced, rational, function focussed forms help elucidate that the functionality, that which a physical instrument or tool for organizing can do, be that an analogue tool or a digital tool, is defined before its development and always in context of the conceptual, theoretical basis of the organizing. Which again is a largely anatomical understanding of organizing; all organs arose for specific functions in context of the pre-defined basis of the respective organism.

Considerations which on the one hand allow a questioning of our contemporary domestic storage objects, those physical tools for organizing we all place in our bedrooms, hallways, living rooms, kitchens, or going back to Frankfurt 1926 are our kitchens per se, and the reality where we all buy the same physical objects, tools, for organizing our domestic lives although our conceptual bases may be, invariably are, very different. Or as a Hans Gugelot once deliciously phrased it, "it is illogical if two consumers with different needs want to have the same cabinet".5 The eight cabinets in the Museum der Dinge temporary exhibition space aren't general objects which the users were left to somehow fit, however imperfectly, into their conceptual organization system. Rather were built to support that system. And what choice does the contemporary furniture industry offer us for our domestic organization? Or the contemporary paint industry? Exactly. Thoughts which take one not only to Gugelot's M 125 system, but back to the USM Haller and System 180 connecting balls and to modularity. To modularity as being genuine organic design.

Considerations which on the other hand allow an appreciation that our physical, tangible instruments and tools for organizing, and our future digital, virtual instruments and tools for organizing, are monetary investments; the eight analogue cabinets wouldn't have come cheap nor will our future digital cabinets. Nor do the myriad small objects we all consume in order to enable our general, unspecific, ubiquitous domestic cabinets to fit, however imperfectly, our organizing systems. And therefore to better appreciate the importance of ensuring any given physical or digital instrument or tool for organizing is fit for purpose before investing, of carefully defining that purpose before investing in physical or digital tools. Which brings us back to Diethart Kerbs' garage. Possibly.

And considerations which allow Organizing Things to help elucidate that for all that new technology can, unquestionably, support new approaches to organization, personal or institutional, it rarely leads the development of those new approaches, rarely leads the development of new theoretical, conceptual approaches; rather, those new approaches start by necessity with someone, be that an individual, a company, a public body, a museum/archive, a whatever, seeking it.

Starts with someone, be that an individual, a company, a public body, a museum/archive, a whatever, reflecting on the whys and wherefores of their own and of others organizing, reflecting on the theoretical, conceptual basis on which they and others organize, questioning the purpose of any given organization, in how far that organization allows one part to co-operate with another, the degree to which the structures and structure thereby created are meaningful in supporting the wider organism be that a society, a company, a home, a kitchen or an archive/museum collection.

Reflections and questioning we all, collectively and individually, only very rarely undertake. Tending as we do to remain in familiar, accustomed, unquestioned patterns, remaining with the systems we've inherited from others or have been taught since an earlier age or which global industry supply. And that not least because it's easier. Change being popularly understood as a synonym of far too complicated to even consider. And not as a synonym of opportunity.

Through the differentiated insights it enables into the Museum der Dinge permanent collection exhibition and the objects contained therein, and also the differentiated perspectives it enables on the myriad contexts in which we all, collectively and individually, continually, borderline pathologically, organize all manner of things, and also the fresh appreciations it enables that we all, collectively and individually, can develop new bases, or can demand new bases, that the bases for our organizing, collective and individual, aren't naturally set but are artificially defined, and understandings it enables that if the physical tools to assist the conceptual basis don't yet exist, we can develop them, Organizing Things is an interesting and entertaining and apposite place to practice developing such reflections on and questioning of organizing. And to appreciate why one should.

Organizing Things is scheduled to run at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Oranienstraße 25, 10999 Berlin until Monday October 31st.

Full information, including information on opening times, ticket prices, current hygiene rules, and details of the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.museumderdinge.org/organizing-things

1We are exaggerating slightly as a rhetoric tool, but only slightly. And not distortingly so......

2Although today the normal British English spelling is "organise" and the normal American English spelling "organize", both Phillips and Johnson employ the Z, a Z also found in the exhibition on title. Thus despite our preference for the S, we stick with Z here for reasons of simplicity.

3We make very deliberate reference to the collection exhibition and not the collection. For although Organizing Things also includes with the so-called Registry a real time demonstration of how a donated collection is incorporated into the museum collection, there is no direct reference as to how the archive is organized, if it is a 1:1 mirror of the exhibition space, or if it is based on a differing concept. Which, yes, would also be interesting and informative to know. But not knowing doesn't detract from Organizing Things.

4Yes, if your listening to an opera or a concerto or a audio book or a 1970s concept album, listening in the proscribed order is meaningful. But if its your Rainy Tuesday and the cat's been sick playlist, shuffling is much more fun. And distracting.

5Hans Gugelot, Beschreibung und Analyse des Baukastensystems M 125, in Werner Blaser, Element-System-Möbel. Wege von der Architektur zum Design, Deutshe Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart, 1984