Monographic exhibitions portraying designers from ages past, generally, only leave you with but little opportunity to directly assess, compare and contrast that designer in context of their time.

The, desired, concentrated focus on the protagonist leaving you, by necessity, not least by necessity of limits of time and space, primarily relying on those snippets of information and/or blurry images of objects, invariably popularly celebrated objects, your brain can recover in that moment, for any semblance of assessment, comparison and contrast with what others were realising in that period, any semblance of assessment, comparison and contrast with the positions and approaches of others in that period.

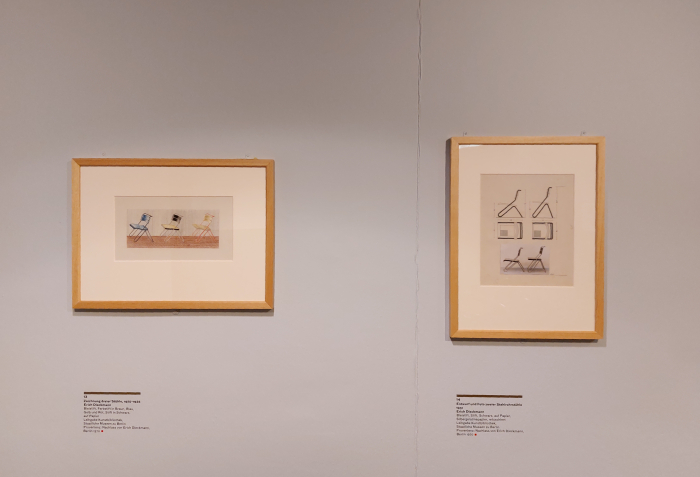

Following its run at Neuwerk 11, Halle, the exhibition Chairs: Dieckmann! The Forgotten Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann is now on display at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, who have employed their own collection to expanded the Dieckmann presentation with contemporaneous works. To expand the works of Erich Dieckmann with works by The Others.......

Chairs: Dieckmann! The Forgotten Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann as presented at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin, is in essence exactly the same Chairs: Dieckmann! The Forgotten Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann as presented at Neuwerk 11, Halle: it still allows for the same, necessarily, brief, yet highly satisfying, overview of an important, interesting, informative, if all too briefly active, and far too anonymous, designer; still demands that after viewing its brief introduction to Dieckmann you begin expanding on the many, necessarily, abbreviated aspects of Dieckmann's life and work; still inspires you to undertake that research, still inspires you to learn more and to approach even closer to Dieckmann. All the chairs are there, the Dieckmann family kitchen cupboard is there, the very satisfying clock with its silhouette of the past is there, the documents are there, the film interspersing actor Bibiana Beglau reading archive documents with Stefan Diez and Rudolf Horn discussing Dieckmann, his work, his legacy, his relevance, is still on constant loop, and still in German only. Regrettably. Still. Was regrettable in Halle and is more so in Berlin, a city who in many regards speaks German as a second language, and who is currently gearing itself up for its first proper tourist summer since 2019. Many of whom will speak no German but (hopefully) be in search of a Germany beyond the tourist gaze.

If a similar presentation in Berlin to that in Halle allowed to express itself in a more open, more relaxed, more accessible, manner than was possible in the confines of Neuwerk 11's historic architecture; if, yes, in the cellar of Berlin's Kunstgewerbemuseum, never the most easily engaging, or warming, or motivating, of spaces. However, in Berlin as in Halle the exhibition design by Diez Office alleviates the more acute shortcomings of the exhibition space and helps keep you focussed on the presentation, keeps you focussed on the objects, keeps you focussed on Dieckmann.

While beyond Erich Dieckmann per se the very pleasing introduction to Erich Dieckmann provided in Chairs: Dieckmann! is ably supported in Berlin, again as in Halle, by the installation Living Like Dieckmann by artist Margit Jäschke and designer Stephan Schulz which not only enables differentiated reflections on Dieckmann but also allows visitors to try out his Chairs, that physical, tactile, aspect all too often overlooked in exhibitions exploring chairs and chair designers; and is further ably supported by Sitting reconsidered. Design, Observe, Stage with its presentation of the results of a semester project undertaken at Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle in context of reflections on and analysis of Erich Dieckmann and his Chairs.

And not only is the presentation in Berlin largely as in Halle, but so is the greater majority of what we opined from Halle, and thus we refer you there dear reader for our thoughts on both Chairs: Dieckmann! and Sitting reconsidered and concentrate here on that which is new in Berlin, for all the extension of Chairs: Dieckmann! into the neighbouring Kunstgewerbemuseum design collection permanent exhibition space and a curated presentation of selected works contemporary to Dieckmann's.

Selected contemporaneous works by The Others.

Works from across genres including furniture, ceramics, glass or lighting; works by protagonists associated with institutions such as Bauhaus Weimar, Bauhaus Dessau, the Deutsche Werkbund, Schönheit der Arbeit, Burg Giebchenstein Halle or the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau; works by protagonists as varied as, amongst many others, Eckart Muthesius, Marguerite Friedlaender, Kálmán Lengyel or Ruth Hildegard Geyer-Raack, the latter represented in The Others by a highly engaging 1935 iron wire chair intended to be used either inside or out and which, we'll argue, can be very much considered in context of, ¿as a continuation of?, the iron wire furniture produced in the Vienna of the mid-19th century by the likes of, for example, an August Kitschelt, and which, as discussed in context of Thonet & Design at Die Neue Sammlung, Munich, possibly, just possibly, could be part of the answer to the eternal unanswered, unanswerable, question of why Michael Thonet adopted his familiar flowing, floral, vine tendril aesthetic. The presentation of works by Thonet in the permanent collection exhibition, and just around the corner from Geyer-Raack's chair, enabling considerations on a possible, potential, association, or not, between 19th century bent wood furniture and 19th century bent iron wire furniture.

A further highlight, certainly for us, of The Others is and was a presentation of objects designed in the early 1930s by Lilly Reich and Mies van der Rohe for Haus Lemke, Berlin, including a low-back, in many regards a no-back, sofa attributed to Lilly Reich which is just the most delicious object, and a work which, we'll argue, has lost nothing in terms of relevance nor delight giving potential in the intervening nine decades. It could be launched tomorrow and still feel fresh, would still demand, force, a contemporary conversation, Less engaging, but, arguably, much more interesting and informative, stands a desk chair accredited to Mies van der Rohe but which, as previously discussed, in its original expression as part of the interior for the mid-1920s Villa Wolf, Gubin, may, just may, have been, (we consider was), the very first joint furniture project between Reich and Mies van der Rohe. And, if so, a very important artefact in the (hi)story of their relationship.

Then there is the reduced and rational Model 700 crockery service by Heinrich Löffelhardt for the NSDAP's Schönheit der Arbeit [Beauty of Labour], an organisation charged with improving efficiency, safety and aesthetics in 1930s German workplaces. A charming crockery service which not only poses the question if one can appreciate objects created for nefarious purposes, if one can find satisfaction in objects promoting the darkest aspects of humanity, but also helps remind us all that the Nazis didn't just employ the völkisch and a manufactured national romantic in their propaganda, rather, and as discussed from Design of the Third Reich at the Design Museum Den Bosch, they were quite open to employing whatever they felt could help them advance their poisonous propaganda. Including the more avant-garde approaches of their opponents. A not unimportant lesson in these fake news, hype and Instagram days of ours. Not that viewers of The Others would necessarily be aware of the link between Löffelhardt's crockery and the NSDAP's infiltration of everyday life in 1930s Germany. For it isn't mentioned. Similarly the Volksempfänger radio on display a couple of cabinets further away, which is innocuously presented as being nothing more relevant than a device all radio manufacturers were compelled to produce in 1930s Germany. Who compelled them to produce such and for all why they would want all radio manufacturers to produce just such a radio, going unmentioned. Although the Reichsadler above the tuning dial, the Reichsadler as the indicator of where you are correctly tuned in, does give a bit of a clue. And then there is the curious reluctance to unequivocally name Walter Maria Kersting (and his students at the Kölner Werkschule) as the Volksempfänger's designer. Why the vagueness?

It is possible to discuss 1930s Germany without using the word "Nazi" or "NSDAP", the question is, is that the best approach to discussing history? Especially in a museum? A museum in Berlin? Surely one needs, for all in a museum, to approach history openly.

As one needs to openly discuss Erich Dieckmann's time in the 1930s working for the Reichskammer der bildende Künste and for the aforementioned Schönheit der Arbeit.

Associations discussed at length in the Chairs: Dieckmann! catalogue1 but presented in the Chairs: Dieckmann! exhibition in a blink and you'll miss it note in his biography.

Considerations on Dieckmann and The Others in context of the NSDAP not discussed, not assessed, not compared, not contrasted in Chairs: Dieckmann! exhibition, considerations on the biography's of Dieckmann and The Others not discussed, not assessed, not compared, not contrasted in Chairs: Dieckmann! exhibition, which bring us back to the primary delight of Chairs: Dieckmann! exhibition in Berlin: the opportunity to directly assess, compare, contrast, discuss the work of Erich Dieckmann with the work of The Others.

In terms of furniture that comparison can be particularly satisfyingly undertaken in context of that material most popularly associated with inter-War design in the contemporary Germany: steel-tubing

A material the vast swathes of wood in The Others helps reinforce didn't enjoy the primacy in inter-War Europe it often appears it did in popular reflections on that period; a material that, as previously noted, Dieckmann considered “ein Kunstprodukt”, an artificial product2, yet despite which, as can be appreciated in Chairs: Dieckmann!, he approached with no less seriousness nor aplomb than wood and wicker. And an approach to steel tubing by Erich Dieckmann The Others allows one to compare directly with works by the likes of Marcel Breuer or Mies van der Rohe who so dominate popular understandings of inter-War steel tube furniture.

A juxtaposition of Dieckmann with Marcel Breuer which tends to lead one, certainly leads us, to a position that while the works of Breuer resemble chairs, the works of Dieckmann resemble invitations to sit. Are an informal enticement not a formal command. And thus awakening comparisons with the positions of, for example, Alvar and Aino Aalto.

And while that invitation is also extended in the sweeping flowing curves of Mies van der Rohe, the presentation in the Kunstgewerbemuseum tends, again certainly for us, to underscore the argument we developed in Halle that the "flowing, curving, sweeping" of Dieckmann's furniture "appears a consequence of a logical reduction and rationalisation", is primarily a construction position, and that "as the only possible solution". Which, and returning to Ruth Hildegard Geyer-Raack's iron wire chair, brings us back to the question of why Michael Thonet adopted his familiar flowing, floral, vine tendril aesthetic? The Others causing us to reflect that as with Dieckmann's curves Thonet's curves appear as the only possible solution to optimising a novel industrial production process through a close cooperation with the material, the only possibly solution to reducing material usage in the interests of material economy, the only possible solution to creating a visually and physically reduced object responsive to contemporary positions. Yes, Dieckmann employed similar strategies with wicker and steel: but both are tubes, one a natural product the other a Kunstprodukt. One just needs to understand the differing characters and respond appropriately. And Chairs: Dieckmann! allows for a comparison of Dieckmann's wicker and Dieckmann's steel. And Thonet's wooden tubes.

In contrast, the flowing, curving sweeping of Mies's chair, although unquestionably informed by the wide arching curves of a Michael Thonet, appear, again for us, primarily the consequence of an aesthetic position, of Mies developing a, for him, visually pleasing form rather than a steel tube form. And thus, we'll argue, a rare diversion into formal considerations for an architect and designer more normally concerned with construction than aesthetics. Sadly the very real limitations of space in the Kunstgewerbemuseum cellar denying the opportunity to directly compare the steel tubing of an Erich Dieckmann or a Marcel Breuer or a Mies van der Rohe with that of a Lilly Reich, or a Heinz and/or Bodo Rasch, or a Hans and/or Wassili Luckhardt, comparisons which would have offered yet further interesting perspectives not only on Erich Dieckmann, but on inter-War tubular steel furniture.

In addition, and away from furniture per se, The Others also allows for very nice reflections on Dieckmann's positions on interiors and the objects of everyday life in context of wider positions on domestic spaces in the inter-War years, allowing as it does for reflections on Dieckmann's place in discussions on, for example, industrial versus craft production, on the relationships of individuals with the spaces they inhabit, or on the question of how to enable good, meaningful, and for all, affordable, domestic interiors. Reflections that can be undertake in Dieckmann-unspecific contexts through, for example, the myriad glass and ceramic objects on display, genres not at the heart of Dieckmann's oeuvre but which as presented in the Kunstgewerbemuseum enable reflections on the contemporary questions of domestic furnishing; and reflections undertaken in Dieckmann-specific contexts through furniture, that genre at the heart of Dieckmann's oeuvre, and for all through the juxtaposition of Dieckmann's Typenmöbel programme for the Bau- und Wohnungskunst, Weimar, with, and amongst other exhibits, Adolf Gustav Schneck's "die billige Wohnung" programme or a collection of dining room furniture by Karl Bertsch, both produced by the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, an institution with whom Erich Dieckmann appears never to have collaborated.

Wandering through The Others, the question, how is that even possible, why didn't Dieckmann and Hellerau cooperate, what could Hellerau x Dieckmann have brought inter-War Germany, inter-War Europe, becomes louder and louder and louder.

As does the question why is Erich Dieckmann so anonymous today? How is that even possible?

No, honestly, how?

A question we discussed at length from Chairs: Dieckmann! at Neuwerk 11, Halle.

And a question The Others allows alternative perspectives on, allows one to approached from a not uninteresting, a not uninformative, alternative direction.

In the diversity and similarity of the works presented The Others is as much the briefest of introductions to design in the lands of the Germany of the 1920s and 1930s as it is an extension of Chairs: Dieckmann!; and as an introduction to inter-War positions is a very nice reminder that the single path design and architecture in inter-War Germany, and by extrapolation inter-War Europe, is often explained as collectively following, simply can't be true. It must be a more complex (hi)story. And as such The Others is in itself a very nice, self-contained, if by necessity very brief, showcase that demands further work by yourself upon leaving.

But for all is a very pleasing extension of Chairs: Dieckmann!, a bilingual German/English extension, an extension which pleasingly places works you will probably have seen by designers whose name you probably recognise alongside works you probably haven't by designers whose name you probably don't, an extension which can be viewed once but which should be viewed in repetition: view Chairs: Dieckmann!, view The Others, go back to Chairs: Dieckmann!, go back to The Others, to Chairs: Dieckmann!, to The Others, to Chairs: Dieckmann!, to The Others, to Thonet and the rest of the permanent collection exhibition, to Chairs: Dieckmann!, to The Others, etc, etc, etc. The more you wander between the spaces the more you discover, the more questions arise, and the more satisfying the experience.

An extension of Chairs: Dieckmann! which neatly underscores not only that an Erich Dieckmann didn't exist and work in isolation, but that no designer does. Any designer, as in any Designer and not someone who markets themselves as a designer, exists in a myriad contemporary contexts, and thereby The Others helps underscore that the relevance of any designer isn't to be understood alone in that which they realised, but rather in that which they realised and the why they realised it in context of its/their time and in context of what The Others were realising at that time.

And thus an extension of Chairs: Dieckmann! which in enabling better informed assessments, comparisons and contrasts of Erich Dieckmann and his oeuvre in a contemporaneous context allows for the development of not only better appreciations of Erich Dieckmann, of the relevance, importance, also the contemporary relevance, importance, of Erich Dieckmann, nor only better appreciations of Erich Dieckmann's place on the helix of furniture design, but also allows one to better appreciate that much as Erich Dieckmann wasn't a singular entity distinct from and independent of The Others, so the helix of design (hi)story isn't one of individuals stamped in time but one of a community, a collective, in continual movement. That all are a component of the others.

Which, yes, does sound like a metaphor ... or possibly just a confirmation of the close relationship between design and society.......

Chairs: Dieckmann! The Forgotten Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann is scheduled to run at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Matthäikirchplatz, 10785 Berlin until Sunday August 14th.

Full details can be found at www.smb.museum/chairs-dieckmann

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious.......

1see Aya Soika, Das Ehepaar Dieckmann im Nationalsozialismus, in Bursian et al [Eds.] Stuhle: Dieckmann! Der vergessene Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann, Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 2022

2Erich Dieckmann, Möbelbau in Holz, Rohr und Stahl, Die Baubücher, Band 11, Jukius Hoffmann Verlag, Stuttgart, 1931, page 69, available via https://www.digishelf.de/piresolver?id=1067053387 (accessed 10.06.2022)