There is an argument to be made that the craft of the glassmaker is as anachronistic in the 21st century as that of the candlemaker: an argument that while the later has seen their craft superseded by the electric lightbulb, the function of the former has not only been increasingly marginalised by the rise of industrially produced glassware, but also by the development of new materials, materials more robust and more durable than the famously fragile and transient glass.

The candlemaker and the glassmaker, so one could further argue, having been reduced to little more than popular attractions at Ye Olde Worlde Village Fayre and similar commercial and pedagogic acts of romanticised nostalgia.

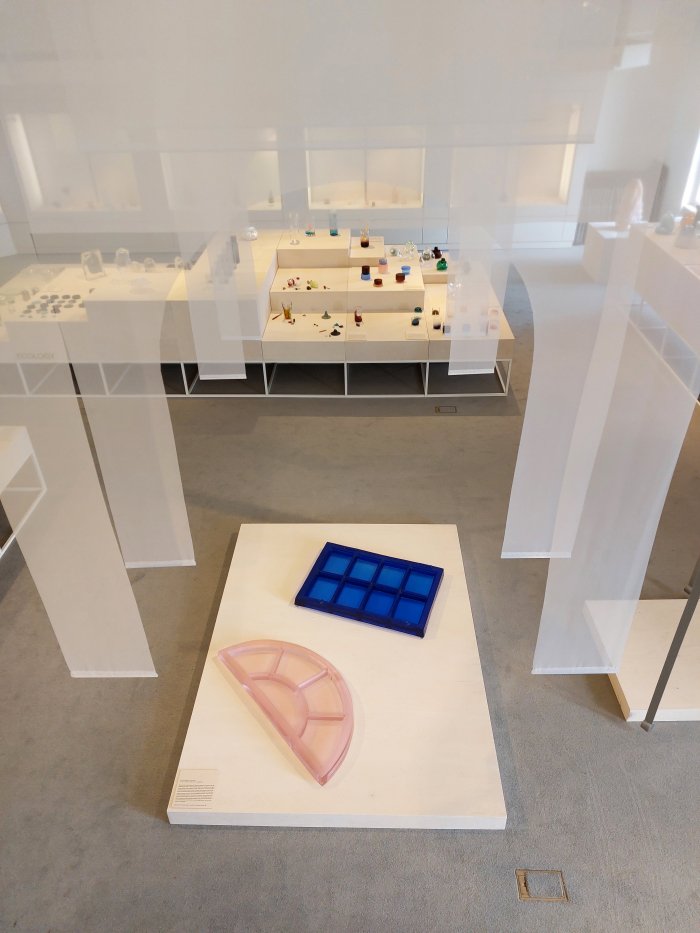

With the showcase Glass - Hand Formed Matter the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, present a convincing counter-argument.......

Initiated by the Weißensee Kunsthochschule Berlin, Glass - Hand Formed Matter is/was conceived as an international cooperation platform which, and over simplifying a little, but at this stage necessarily so, has at its core projects developed by students from Weißensee, the Aalto University Helsinki, Konstfack Stockholm and Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle1, projects developed by the students in cooperation with craft orientated glass works in Germany, Sweden and Finland. Cooperation projects which, as the title neatly implies, are primarily focussed on the forming of glass, on exploring the myriad processes involved in glass forming, on exploring future orientated glass forming processes, and for all, certainly in our interpretation of the projects as presented in the Bröhan Museum, projects focused on achieving an easy, ready, variability in glass production, of achieving, if one so will, a controllable freedom in glass production akin to that which 3D printing allows in plastics or ceramics or concrete.

A challenge approached in Hand Formed Matter via the development of numerous novel production process which allow for formal variation in the moulds and thereby in the objects: novel production processes proposed in projects such as, and amongst others, Kolosseum by Andrea Bensi together with Torsten Kunze from Glasmanufaktur Harzkristall, Derenburg, Germany and Peter Kuchinke from The Glass Factory, Boda, Sweden, which envisages a mould formed from a series of metal rods which can be removed/added/lifted/lowered/shifted as and when required; Converging Disciplines by Moritz Müller and Henrieke Neumeyer with Tortsen Rötzsche from Harzkristall and Peter Kuchinke which harnesses the aforementioned formal flexibility of 3D printed ceramics as the basis for producing moulds for formally flexible glassware; or To Assemblage by Paul Flanders in cooperation with Heikki Punkari from the Glass Studio at Tavastia Vocational College, Hämeenlinna, Finland which employs a series of freely interchangeable, reversible, forms as a modular mould enabling the realisation of a wide variety of glass objects.

And freely variable production processes which although presented in Hand Formed Matter as explorative, speculative, positions, do offer insights into possible future serial production processes......

.......¿serial production?

Yes, serial production.

¿We thought Hand Formed Matter was about craft, the craft of glassmaking, the future of glassmaking? ¿About, well, hand formed matter?

¿Yes, it is......? Ahhhh...... we think we see the confusion, craft, we presume your assuming, is about the unique, the result of individuals working with a few traditional, ideally primitive, tools, is an Olde Worlde position that was superseded in the first decades of the 20th century by industry. Yet as so oft in life, it's not that simple, and as, for example discussed, ¿implied?, from Craft is Cactus at the Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt, craft didn't freeze in its, then, reality, didn't wither, didn't stop, with the rise of mass industry in the first decades of the 20th century, rather craft adapted to the new environment, re-defined its position in the age of the soulless machine, and, and importantly, continued to be the source of inspiration for industry it had been since the last decades of the 19th century. And that, we'll argue, for good reason: as, again, discussed from Craft is Cactus, craft is, essentially, less a skill and primarily a relationship with a particular material, and craftsfolk, certainly the good ones, have thus by definition a highly nuanced understanding of their materials and consequently are best suited to finding new ways and means of working with, employing, processing etc, that material. Of developing their craft and providing thereby new impetuses for society, both technical and aesthetic impetuses, and also new impetuses for industry, both technical and aesthetic impetuses. A highly nuanced understanding that, again we'd argue, becomes particularly interesting and important in conjunction with a designer looking for a solution to a specific problem, a problem the crafter may not have seen on account of their focus on the material rather than the designer's focus on the processes of contemporary society. Cooperations, joint problem solving exercises, which again go back to the late 19th century and whose rise, in many regards, marks the origins of design as an autonomous profession, and of the separation of the once unified form-giving and form-producing processes in objects of everyday use.

And the origins of the integration of design into the production process. The origins of, as for example discussed in context of the book Monobloc by Hauke Wendler, or, in many regards, the work of a Louise Brigham, design as about more than just developing forms, but also about developing production processes to enable the supply of objects of everyday use to an appropriate quantity and quality and price. To enable an appropriate supply of objects of everyday use in an growing, increasingly complex, world, craft production alone, with the best will in the world, would struggle to meet.

The inter-related hows, in many regards, forming the basis of one of the central discourses concerning our objects of everyday use since the early 20th century. Yet whereas in decades past there was a majority belief that the answer was producing at ever larger scales in a global context, of late we've slowly started to appreciate that may not be the case, that that may in fact be toxic; slowly started to appreciate that the production scales need to be but appropriate, and that that production can be local. Appreciations, arguably, brought even more sharply into focus by the Covid pandemic, the associated global supply chain problems and the subsequent urgent questioning of how and where we produce our objects of everyday use.

A contemporary questioning craft has a key role in resolving, not necessarily as producers themselves, although there is a contribution to be made; but certainly, necessarily, a key role in the development of novel, scaleupable, readily variable, production process that can allow future orientated, responsive, global local production. A key role in developing new serial production processes.

Not that craft and crafters contemporary relevance is limited to the development of novel production processes.

Nor is Hand Formed Matter.

Despite our focus above on production process, the student/glassworks cooperations advanced by Hand Formed Matter also saw projects realised which explore numerous other aspects of glassmaking, other aspects of our relationships with glass and the functionalities of glass, projects which employ the glassmaker's nuanced understanding of glass not just to realise objects as objects, as commodities, in their own right, but to develop more conceptual explorations of glass, and which as conceptual, speculative, projects enable differentiated insights into the material, the cultural good, glass.

Conceptual projects which in their diversity and non-defined destination help underscore one of the other values of a platform such as Hand Formed Matter: helping design students develop their own positions to and understandings of design and the role and function of a designer, helping design student's formulate questions and define approaches towards possible answers, helping design students appreciate the role of material in any object/system and thereby the craft origins of their trade. Glass in its possibilities and limitations, in its simplicity and complexity, in its eternity and transience, in the romance and brutality of the furnace flame, in the all too easy belief that after untold centuries of use there can surely be nothing new to be achieved ....... but there always is, being a particularly apposite medium for such a student project. And thus, and as ever with such programmes, each and every project on display has a value to the student that goes way above any object realised or what the project can teach us as viewers. Or at least should have a higher value, if the student was paying attention. Which we assume all were.......

And conceptual projects including, and amongst a great many others, Elements of Colour by Michelle Müller in conjunction with Peter Kuchinke & Tortsen Rötzsche which plays with the differing physical properties of glass depending on which metal oxide is added as a colouring agent; Bone - from waste to valuable resource by Ella Einhell with Peter Kuchinke which explores the structural and decorative possibilities of adding bone ash to glass, yes non-vegan glass, surely the perfect product for all steak porn restaurants; Ordre Coulant by Christian Amann with, again Peter Kuchinke, a project we first saw in context of table talks — Tischgespräche at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden, and which in reflecting on the processes of formal table setting in 18th century high society allows access to reflections on the social (hi)story of glassware; Pintti by Aura Latva-Somppi and student glassmakers from Tavastia Vocational College which in its use of salvaged, old, glass alongside new glass not only touches on the recycling of glass, on the often hidden technical problems of combining glass from different sources, but also through the extreme fragility of the objects realised very pleasingly employs glass as an artistic metaphor; an artistic function of glass, the intrinsic characteristics of glass and our relationships to glass employed as a path to wider, more philosophical, positions, also reflected, pun intended, in To talk and think with a window by Sarah Maria Yasdani which takes the unremarkable glass window to outlandish extremes.

Artistic functions of glass, understandings of glass as more than a commodity, of glass as more than physically functional or decoratively functionless further expanded upon in the Bröhan Museum via six cooperations between the participating glassworks and international artists/artistic collectives; cooperations every bit as core to Hand Formed Matter as the student cooperations, but which for structural reasons we felt obliged to somewhat, and most unfairly, demote in our introduction

Cooperations including A Medusa Glass Study in which artist Tue Greenfort and glassmaker Peter Kuchinke developed a family of glass jellyfish which both fascinate in their aesthetic and also enable differentiated considerations on our ongoing poisoning of the oceans; Cut Out Colliers in which Ingela Johansson explores the (hi)story of socialist Sudeten German glassworkers who following the end of the Second World War fled Bohemia to the DDR where they helped establish glass works such as VEB Gablona in Jüterbog, where they continued to develop their Bohemian glass art, and which thus allows access to reflections on the globality of that which we consider regional and on the importance and relevance of migration, whether forced or voluntary, in the development of societies, objects and rituals; or Un/Making Soil Communities at Nuutajärvi Glass Village by Riikka Latva-Somppi and Un/Making Studio which explored the consequences of glassworking on the local environment, specifically soil pollution through heavy metals and the subsequent effects on the flora around a glassworks. And a project which also helps highlight that going forward one of the main challenges for the glass industry at all production levels is inarguably reducing the energy footprint of glass production: glass, as we all know, and despite what the project title implies, isn't a hand formed matter but a heat formed matter, and that heating is, as best we can ascertain, and/or our information may be outdated, not only relatively energy intensive but energy inefficient with calculations suggesting that only some 40% of the energy employed to melt glass is actually involved in melting glass, the rest being lost as heat, water vapour, etc2, a situation which reminds very much of the old incandescent light bulb. And is as equally unsatisfying. And tends to underscore that the development of new glass making technology, new glass melting technology, is as important as new glass forming processes. Or, and perhaps the better option, that those new forming processes should be based on new rather than old technology.

Rounded off by a small, bilingual German/English, educational island which helps explain where glass comes from, how glass is shaped or coloured and what glass is/can be, and extended by a presentation of a century and a quarter of glass objects from the Bröhan Museum's collection from artists/designers/manufacturers as varied as, and amongst many others, Emile Gallé, Glasfabrik Johann Lötz Witwe, Josef Hoffmann for J & L Lobmeyr or Wilhelm Wagenfeld for Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke, a presentation which both reflects the Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Functionalism of the museum's full title, that area of speciality of the Bröhan Museum, and also helps underscore that approaches to and understandings of glass have long been in flux, have long been informed by, and helped inform, wider aesthetic, social and cultural realities, and will continue to be so, Hand Formed Matter is as much a platform focussed on motivating the viewer to reflect anew and afresh on glass as it is a platform focussed on motivating artists/designers/glassmakers to reflect anew and afresh on the future of glassmaking.

A platform which in taking the viewer beyond the technical functionality of specific objects, without ignoring such, and beyond the functionless decorative of specific objects, without ignoring such, and towards the practicalities, problems and possibilities of producing glassware, towards the complex nature of our myriad relationships with glassware, towards the sensory and emotional functionalities of glass, towards differentiated insights into the place and role of glass in contemporary society, towards the importance of that inherent fragility and transience of glass, Hand Formed Matter neatly and concisely underscores that much as candles bring a lot more to a space than just light, something celebrated by the lighting design Charles and Ray Eames employed in their own home, glass isn't just technically functional and functionlessly decorative, and thereby allows one to better appreciate not only why it is important that glassmakers continue to develop and evolve the craft of glassmaking, but why that development and evolution requires input from and cooperation with designers (and engineers). And why that development and evolution is relevant for us all.

And in doing such also allows for important wider reflections on craft in our contemporary and future realities. Reflections on craft without the heavy shroud of nostalgia.

Glass - Hand Formed Matter is scheduled to run at the Bröhan Museum, Schlossstraße 1a, 14059 Berlin until Sunday August 7th.

Full details can be found at www.broehan-museum.de

Following its presentation Glass - Hand Formed Matter will tour through Germany, Sweden and Finland. Sadly there is no project website, nor can we find a confirmed tour itinerary, thus see local press for details.3

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious…….

1Might not be entirely true. We're fairly certain that students from Weißensee Kunsthochschule Berlin and Aalto University Helsinki are involved, and that Konstfack Stockholm and Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle are in some way involved, but aren't 100% sure as to the exact details. And that not least because in the exhibition the individual students' institutional associations aren't listed. Which on the one hand is fine, is arguably unimportant, but would be helpful.

2There is also a second touring exhibition in context of the Hand Formed Matter platform, Wasser und Wein, which presents objects for the delectation of...... water and wine. Until Sunday June 26th Wasser und Wein can be viewed at the KunstForum Gotha.

3Clearly there are differences depending on furnace type and the glass product being produced, but, as far as we can ascertain, and/or our information may be outdated, glass melting is very energy inefficient. Which in our contemporary world, it can't be.