"...one only finds warmth of life and sincerity where human nature is allowed to flourish", opined the German designer Erich Dieckmann in 1931, "one shouldn't forget that in our apartments. Let's treat our contemporary homes to something humane. Something unelaborate, something provisional, with some leeway and space for things to grow as they wish over time."1

With the exhibition Chairs: Dieckmann! The Forgotten Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann, the Kunststiftung des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt and Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin extend an invitation to explore how Erich Dieckmann understood an unelaborate, humane, contemporary apartment full of leeway and space to grow.......

Born on November 5th 1896 in (the then) Kauernick, West Prussia, the contemporary Kurzętnik, Poland, Erich Dieckmann was raised in Bad Bentheim and Goslar before in 1913 joining the merchant navy. A career at sea abruptly halted by the outbreak of the Great War; Dieckmann voluntarily signing up in 1914 and seeing service in Flanders, where, in April 1915 an explosion cost him not only the index finger of his left hand but much of the mobility in his left arm. And thereby also cost him his planned career as a sailor. Thus in October 1917 Dieckmann enrolled to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule in, then, Danzig before in 1920 switching to Dresden where he studied painting, and where he met and married Katharina Ludewig. In 1921 the Dieckmanns moved to Weimar where, following completion of Johannes Itten's Grundkurs, Erich Dieckmann joined the Bauhaus carpentry workshop under the direction of Walter Gropius, passing his Gessel, Journeyman, exam in 1924.

When Bauhaus announced its enforced move from Weimar Erich Dieckmann chose not to travel with them to Dessau; instead applying, unsuccessfully, for a position at Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule, Halle, and, ultimately, and arguably fortuitously, taking up the post of Artistic Head of the carpentry and interior architecture department at the Staatlichen Hochschule für Handwerk und Baukunst a.k.a. the Bauhochschule, Weimar; the formal Bauhaus Weimar successor institute; an institution which kept the focus more on the arts and crafts a new entity that defined early Bauhaus Weimar, before art and technology became the new Bauhaus dream team; and an institution which also counted ex-Bauhäusler such as Wilhelm Wagenfeld or Otto Lindig amongst its teaching staff.

In addition to his teaching work the late 1920s also saw Erich Dieckmann continue the interior design practice he had begun at Bauhaus and also saw him begin selling his furniture designs through the Bauhochschule's commercial platform, Weimar Bau und Wohnungskunst, the first of numerous commercial furniture cooperations Dieckmann would undertake.

Then, as so oft in European (hi)story, after the 1920s came the 1930s, specifically 1931 when, against the background of changes at the Bauhochschule enforced by the NSDAP, Erich Dieckmann was relieved of his duties; allegedly on account of failing qualifications, the reality, in all probability, is much more that Dieckmann's positions to and expressions of furniture design were too far removed from the völkisch the NSDAP demanded. And changes in Weimar that, once again, saw Dieckmann apply to Burg Giebichenstein, this time successfully: on May 4th 1931 Dieckmann taking up the post of Artistic Head of the carpentry workshop in Halle. Until May 21st 1933, when, once again, he was relieved of his duties, this time as a consequence of cost-saving measures. And thus the exact same reason/excuse that was given for ending Margarete Junge's Professorship at the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden in 1934; whereby, while one gets the impression Junge was forced into an unwanted early retirement on account of her, let's say, less than supportive position as regards the NSDAP, with Dieckmann, once again, one senses the real reason is to be found in his positions to and expressions of furniture design.2

And indeed unlike Junge Dieckmann was a member of the NSDAP; and as Aya Soika convincingly discusses in the Chairs: Dieckmann! catalogue3, while his, and Katharina's, joining of the NSDAP on May 1st 1933, a period when rumours of imminent cost-saving measures at the Burg would have been doing the rounds, could be seen as a necessary evil in an attempt to stave of a feared potential redundancy, there is also evidence, strong implications, that it was a membership born of conviction. What is much clearer is the energy and fervour with which Erich and Katharina sought to overturn the decision to end his tenure at Burg, albeit without success. And what is equally clear, or at least presented as clear by Aya Soika, whom we see no reason to doubt, is that had Dieckmann not possessed a "personal position freely open to National Socialism"4, or at least convinced everyone he did, he would have had great difficulty finding work after 1933. And initially he did have great difficulty, operating unsuccessfully as a freelancer while applying, equally unsuccessfully, for untold positions with state bodies, before in 1936 he took up a position in the Hannover office of the quasi-official organisation Schönheit der Arbeit [Beauty of Labour], that agency which, as we noted from Design of the Third Reich at the Design Museum Den Bosch, was charged with not only improving workspaces aesthetically but also in terms of safety and efficiency, and for whom Dieckmann, as best as can currently be ascertained, designed interiors, furnishings and furniture, before in 1939 he switched to a purely administrative position with the Reichskammer der bildende Künste in Berlin, where he saw out the War. Or at least the greater part of it.

Erich Dieckmann died in Berlin on November 8th 1944, three days after his 48th birthday, as a consequence of a long standing cardiological condition.

Since when he has fallen into a popular forgottenness.

A popular forgottenness which as Chairs: Dieckmann! allows one to better understand, is not only most unjust, most unwarranted, most unbefitting. But also most unhelpful.

A bijou exhibition in scale if not scope, Chairs: Dieckmann! allows one to approach Erich Dieckmann, his work and his contribution to the (hi)story of furniture design via three platforms: on the one hand a (German only) film in which the actor Bibiana Beglau reads from archive documents and Stefan Diez and Rudolf Horn, thus a designer of a younger generation and one of an older generation, and one from Germany West and one from German East, discuss Dieckmann and his work, his legacy, his relevance. On the second hand the installation Living Like Dieckmann by artist Margit Jäschke and designer Stephan Schulz which offers you the chance to do that which exhibitions heavy with seating objects rarely allow you the opportunity to do: sit down. To try out contemporary re-editions of some of Dieckmann's chair designs. And that in a room installation populated by objects of art and design by both colleagues of Dieckmann such as Marguerite Friedländer, Josef Albers or the aforementioned Wagenfeld, and also works by more contemporary creatives, including and amongst many others, Inga Sempé, Anna Helm, Margit Jäschke or Stephan Schulz. And which also features a small library, a library with a heavy Bauhaus focus, and also copies of Dieckmann's 1931 work Möbellbau5 in which he presents his thoughts on furniture construction and a fulsome, if confusingly not complete, presentation of his oeuvre until that point, and a library visitors are invited to peruse at their leisure. While sat in and on Dieckmann's designs. And thus is an opportunity to move away from the exhibition per se, and reflect in wider contexts. Is, if one so will, an analogue interactive room installation which allows leeway and space for things to grow. Thus most fitting.

And on the third hand, through a presentation of Dieckmann's works; a presentation which although brief in terms of number of objects, is wide enough in scope to allow an introduction to the whats, whys and hows of Dieckmann; and after so many years of forgottenness a brief introduction is perhaps the best way to approach Erich Dieckmann rather than the shock of overload. Move in slowly, establish a basic understanding, and build from there.

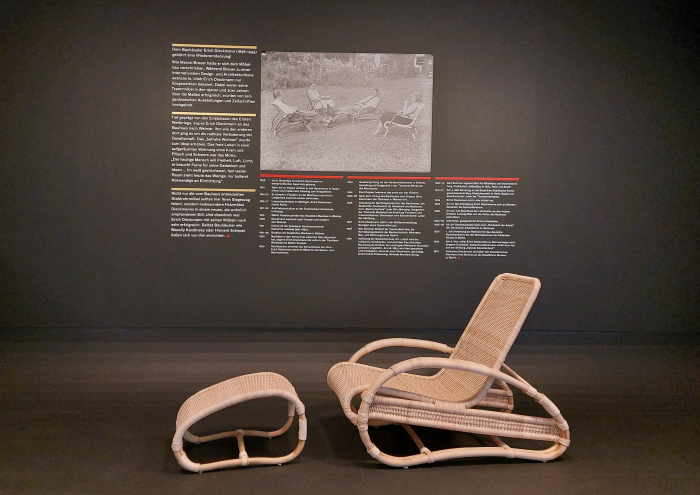

Including establishing a basic understanding of, for example, the role of materials in Dieckmann's oeuvre. Employing an essentially craft approach Dieckmann, as Chairs: Dieckmann! allows one to appreciate, works with the material, employs the properties and conditions set by the material, to find the solution he is searching for rather than using a given material to construct an already defined solution. And also to understand that while others in Germany were forming furniture from steel tubing in the 1920s and 30s Dieckmann was forming furniture from ligneous tubing: in Möbelbau Dieckmann opines that, "through inferior overall quality - production as well as design - wicker furniture has been kept at a level that it is capable of far exceeding", a capability to achieve more than it was achieving he very ably demonstrated wicker furniture possessed.

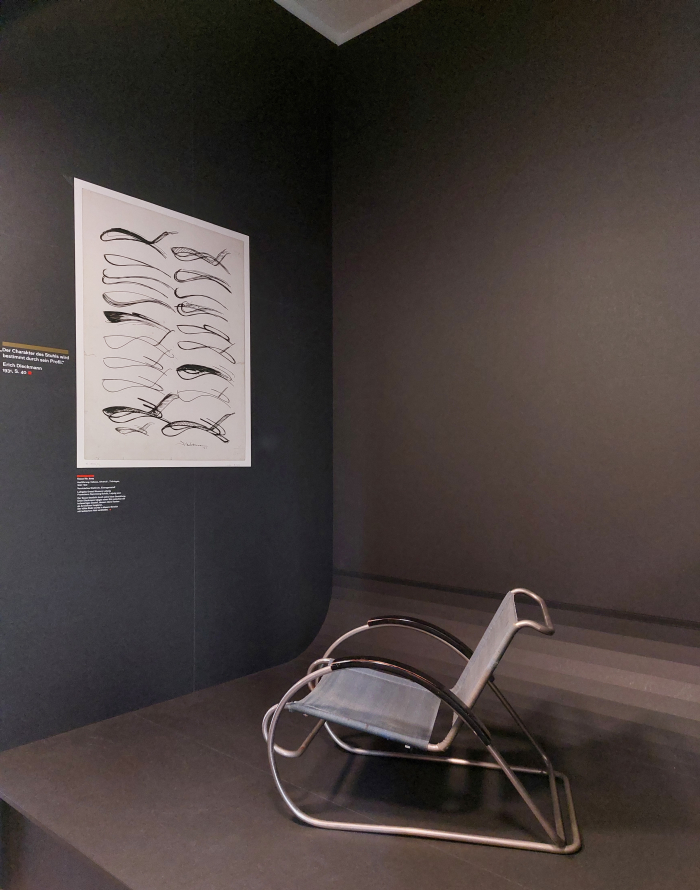

Or establishing a basic understanding of the role of construction in Dieckmann's oeuvre. Simplifying perhaps more than is prudent, a key to Dieckmann's furniture can be found in how he constructs the works, how the construction is more than a technical means to an end but a component of the whole. And how that construction is exposed, an openness of construction which enables an openness of communication, an openness of form, an openness of character; it is, and now generalising and simplifying, essentially, a constructivist approach, very much in context of the faktura and tektonika of his Russian contemporaries, if less brutal, and also in context of his Dutch contemporaries, a great many of Dieckmann's pieces reminding of the sort of objects a Piet Klaarhamer or a Gerrit T Rietveld were producing in early 20th century Utrecht. Dieckmann's works being, arguably, softer, less ideological, more humane.

Or establishing a basic understanding of the role of geometry in Dieckmann's oeuvre. While Dieckmann was very proficient and prolific with the quadratic that is today so closely associated with inter-War design, and also with the triangle that was a key component of the expressionist tool-box at Bauhaus Weimar but which is less celebrated today, a great many of Dieckmann's works also flow and curve and sweep in an abstracted organic manner, without ever losing themselves in all too obvious replications of nature or in the formal opulence of, for example, much of French Art Nouveau; rather the flowing, curving, sweeping appears a consequence of a logical reduction and rationalisation, as the only possible solution. And thus very much akin to many of the works of the Aaltos, or going a century further back a Michael Thonet.

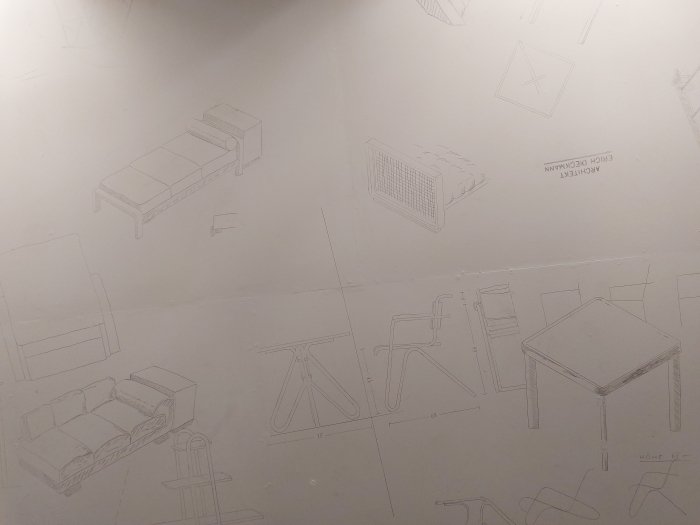

Or establishing a basic understanding of the role of frugality in Dieckmann's oeuvre. Not aesthetic frugality, the majority of Dieckmann's work possessing that easy, rich, disarming charm and beauty that arises from an honesty of intent coupled to an honesty of implementation, but a material frugality, Erich Dieckmann only very rarely using a millimetre of material more than is absolutely necessary. And also employing standardisation to aid and abet that material frugality in industrial production.

Or establishing a basic understanding of the role of Dieckmann's oeuvre in the (hi)story of furniture design. For all its stunning unassumingness today, for its time it is representative of a minor revolution, and that not just in terms of what it is but why it is, and how the what and why relate to Dieckmann's understandings of contemporary furniture, furnishings and interiors. Or perhaps better put, Dieckmann's furniture stands in Halle as not just as a witness to, but as an active protagonist of developing and evolving approaches to and understandings of furniture design at that time, of a move to an ever greater visual and physical and material lightness appropriate for contemporary apartments and contemporary society. Evolutions and developments Erich Dieckmann may not have initiated, but to which he elegantly, convincingly and intelligently contributed.

And a brief introduction to Erich Dieckmann's oeuvre which leads one to pose the question how could Erich Dieckmann fall into popular forgottenness.

How is that even possible?

No, honestly, how?

There are, invariably, a whole host of both independent and interdependent possible reasons; however, for us one of the more convincing arguments is the reality that any designer who is no longer with us invariably exists in one of two ways: they are either a mythos or they are anonymous. And the shadow of the former ensuring the latter remain so.

Something Bauhaus, more precisely the Bauhäusler, is/are textbook example(s) of: alongside the half dozen or so Bauhäusler everyone can name, there stands in the shadows the overwhelming majority, hundreds of Bauhäusler known but to their families and to archivists. If known at all.

In which context one of the more interesting comparisons one can frame Dieckmann in is that with Marcel Breuer: the two were fellow students in the Weimar carpentry workshop under Gropius; they shared responsibility for the majority of the furniture and interior design of the Haus am Horn show home presented at the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition; both had a hang in their furniture to a constructivist rationalisation; both passed their Gessel exam in 1924. Yet whereas Breuer is today celebrated at the core of furniture design (hi)story and stands as a personification of Bauhaus, Dieckmann....... . A state of affairs which on the one hand, arguably, is related to the fact Breuer moved not only to Dessau but to America, and thus post-War when Bauhaus, largely the Dessau incarnation, was raised by the MoMA New York to its near mythical position in the pantheon of design, when all other inter-War German design schools were wiped in a single sweep from the narrative of furniture design (hi)story, when Bauhaus became the synonym for inter-War design in Germany, Marcel Breuer was very visible. And remains so.

And that, not least, on account of his association with steel tube furniture. A form of furniture developed by a great many in the 1920s and 1930s but which is universally uniquely associated with Bauhaus Dessau. And steel tubing Dieckmann also worked with; whereby Otakar Máčel opines that Dieckmann's turning to tubular steel should be understood more from necessity than desire, that steel tubing for Dieckmann was "a fait accompli, a fact that he had to deal with"6, and in the aforementioned book Möbelbau Dieckmann refers to steel tubing as "ein Kunstprodukt", an artificial product, and, and while trying to talk it up, notes that it has an inherent "lack of warmth compared to natural material"7, which, yes, does sound slightly negative, does sound very much like an Alvar Aalto. And is certainly diametrically opposed to, for example, a Charlotte Perriand who in 1929 while expounding the virtues of metal for furniture production denounced wood as a "vegetable substance, bound in its very nature to decay".8 We believe it's fair to say Erich Dieckmann was very much a proponent of vegetable substances over artificial products. Of materials that develop over time rather than remain fixed in time.

Yet as one can appreciate in Chairs: Dieckmann! he employed steel tubing with great aplomb, in genuinely engaging and articulate manners, and that most famously in cooperation with the manufacturer Cebaso, another forgotten protagonist of inter-War design in Thüringen. Albeit as one can also appreciate in Chairs: Dieckmann! he employed steel tubing with the flowing, curving, sweeping approach of his wicker furniture and thus, and as with works by contemporaries such as a Heinz Rasch, a Bodo Rasch or a Giuseppe Terragni, a formal expression which doesn't echo the cubism of a room the way the more quadratic steel tubing of a Mart Stam or Marcel Breuer does; a failing echo Heinz Rasch understood as the reason for the lack of success of his tubular steel designs. And a primacy of the cubic validated today by both the primacy of the cube in popular understandings of inter-War design, and also by the lazy, ubiquitous, use of empty terms such as "classic" or "icon" in context of a Stam or a Breuer. And which keeps a Terragni, a Rasch, a Rasch or a Dieckmann in the shadows.9 Kept there, as with the primacy of Bauhaus in inter-War design, by nothing more than unquestioning convention.

And on the other hand Dieckmann's contemporary anonymity is invariably, inarguably, linked with his death aged just 48, which is still very youthful for a designer; lest we forget Dieckmann's contemporary Arne Jacobsen was 50 when he released his Ant, and 56 when he released his Egg, Ettore Sottsass was 64 at the opening of the inaugural Memphis exhibition in September 1981, while Gio Ponti was approaching 80 when he developed the Gabriella chair and the wider Apta collection for Walter Ponti. And for all an early death in 1944, which meant that much like a Lilly Reich or an Aino Aalto who tragically passed away at around the same time, Dieckmann didn't have the opportunity to develop that which he had started pre-War post-War and thereby develop a post-War biography, a post-War existence, a post-War validity. And which, for example, the aforementioned Arne Jacobsen did: as we all remember from Arne Jacobsen - Designing Denmark at Trapholt, Kolding, Jacobsen's inter-War works not only feature the flowing organic curves that Dieckmann employs as a structural (and?) decorative element, nor only features the use of the wicker Dieckmann was so partial to, but the character and attitude of much of Jacobsen's inter-War works are very much akin to much of Dieckmann's oeuvre. How would Arne Jacobsen be remembered today if he had died in 1944, before his Ants and Eggs and Giraffes? Had Dieckmann been allowed to age, be that in Germany West or Germany East10, how would he have developed as a designer, how would he have contributed to the necessary post-War re-housing and re-furnishing, how would he have responded to the rise of 3D moulded plywood, how would he have responded to the rise of plastics; but he tragically died in 1944 aged just 48 and so remains very much an inter-War designer.

Which as Chairs: Dieckmann! helps explain he very much was. But also that he very much isn't. Helps one appreciate that he is very much a designer with contemporary relevance. He just needs to be better understood, in both his time and in ours.

Staged by the Kunststiftung Sachsen-Anhalt in conjunction with the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin and the Kunstbibliothek Berlin - the former of whom are staging their own parallel exhibition Sitting reconsidered. Design, Observe, Stage at the Burg Galerie, the latter two of whom will host Chairs: Dieckmann! and Sitting reconsidered after their runs in Halle - Chairs: Dieckmann! is, much like Dieckmann's furniture, a very simple affair where it is all too easy to confuse the simplicity for a lack of complexity, a lack of depth, a lack of opportunities for meaningful engagement.

A presentation which in addition to the Chairs of the title also features a multi-purpose cupboard/shelving unit built by Dieckmann at Bauhaus Weimar, used by family Dieckmann for many decades, a work whose clear, unequivocal, segregation of its functionalities defines the form and allows for a unified whole that exists beyond the sum of its individual parts, and a work which can be considered as fulfilling Dieckmann's position that "for a contemporary kitchen, the primary priorities that must be fulfilled: time-saving and space-saving functionality"11; a 1931 buffet clock designed for Otto Bamberger, one of the leading European importers of rattan and wicker at that period, a work that plays with the silhouette of the traditional wooden buffet clock, but in steel tubing, and a work whose direct but in no way impolite formal expression and the playful manner in which the clock body and frame are both simultaneously associated and disassociated means it can be considered an improvement on a non-existent Marianne Brandt object, a phrase we never thought we'd use; and also features a presentation of archive documents, photos and draughts which allow for a wider perspective on Erich Dieckmann and his work.

If a presentation that for all the scope it has, could be a lot wider, Dieckmann's interior design, for example, comes far, far, too short: yes, the exhibition title specifies Chairs, but a great many of Dieckmann's chairs were designed for interiors, and in Dieckmann's oeuvre interior design was not only a large component, but an important component in the development of his positions to and understandings of not just seating, but relationships to furniture. Similarly his Typenmöbel, his programme furntiture12, comes far, far too short: yes, the exhibition title specifies Chairs, but his Typenmöbel programme with its reduced, rational, open form, its frugal use of material while maintaining a richness of character and the prediction of palette furniture clearly readable in many of the chairs, was, arguably, more democratic, less about furniture as being representative of status and more about utility, than others had achieved by the mid-1920s, and Typenmöbel that can thus tell us a lot about Dieckmann. A Dieckmann whose standardised stacking storage system also comes far, far, too short; yes, the exhibition title specifies Chairs, but the use of a standardisation not based on "mathematical formulas" but on "truer to life"13 human scales and the tools of contemporary human life, also helping explain Dieckmann, while the way in which the stacking storage systems, and the chairs, are presented in Möbelbau alongside images of humans and their tools, reminds one very much of a Kaare Klint, another of Dieckmann's contemporaries who concerned themselves with questions of contemporary interiors responsive to contemporary humans and society. And a presentation that could also feature a lot more chairs; yes, the exhibition... title....... specifies......... Chairs............. you can never view too may Erich Dieckmann chairs, each and every one possessing the possibility to teach you more not only about Erich Dieckmann, but about chairs and sitting and seating and furniture design and the relationships between our objects of daily use and wider social, cultural, political, economic et al realities.

That said, as noted above, perhaps after so many years of forgottenness a brief introduction is the better way to approach Erich Dieckmann rather than the shock of overload. And as a presentation Chairs: Dieckmann! not only allows one to better approach Erich Dieckmann, and better appreciate the work of Erich Dieckmann, but also to better approach and appreciate the context in which that work arose.

Allowing as it does for reflections on the fact for all the prominence placed today on steel tubing in inter-War furniture, in the homes of the actual 1920s and 1930s wood was very much in predominance, the vast majority of inter-War homes had no steel tube furniture. Had wooden furniture; wooden furniture which, as with that of an Erich Dieckmann, is often more expressive of the positions of the period in regards of furniture, furnishings and interior design, than the steel tubing of the period. Which, as ever, isn't to denigrate steel tube furniture, is to demand better understandings of why it's arrival marks an important moment in the (hi)story of furniture design. It wasn't because people used it.

Reflections on the fact that Bauhaus is a lot more than it is often presented as. That while Bauhaus was as Tomás Maldonado later opined, a "progressive, anti-conventional stance – striving to make a contribution to society in its own historical situation"14, it wasn't a unified understanding of what that meant or the path thereto. And the differences in opinion amongst the Bauhäusler, for all in the Weimar incarnation, are in many regards more important, informative and instructive than the points of agreement. But less often actively discussed, Bauhaus tending to be popularly understood as an homogenous mass.

Reflections on relationships between the NSDAP and creatives of the 1920s and 30s. As previously noted, for all that Bauhaus is often presented as being an opponent of the NSDAP, an antithesis, there were (a great) many within the school sympathetic to the NSDAP's positions, the political debates on the streets of early 1920s Weimar also being undertaken within the walls of Bauhaus. In addition the likes of an Egon Eiermann, a Mies van der Rohe or a Herbert Bayer cooperated with the NSDAP on numerous projects, for all exhibitions and thereby helped validate the NSDAP and their positions. Walter Maria Kersting and his students at the Kölner Werkschule gave the Volksempfänger VE 301 radio its form and thereby helped bring Nazi propaganda into the homes of 1930s Germany. There were a lot of points of interaction between creatives and the NSDAP, when at varying degrees of activeness, and which need to be better understood and more widely acknowledged. In Dieckmann's case there is a lot more research to be undertaken into exactly how he contributed to Schönheit der Arbeit's output, and also to the promotion of objects of daily use in his duties at the Reichskammer der bildende Künste, not least in context of the fact he was clearly not prepared to change his own approach, sacrify his positions, in order to remain in gainful employment as a furniture designer. Research we hope can be undertaken, that the necessary files are slumbering anonymously in some archive.

But for all Chairs: Dieckmann! allows for reflections on how one brings "warmth of life and sincerity" into an interior space, for all in an age of "progress and advancement and upward development"15, an inter-War demand that finds an echo post-War in, for example, a Verner Panton's position that in developing interior spaces in context of contemporary realities, "l’homme reste l’élément central"16, man remains the central element, and Panton's many considerations on how one develops a sense of well-being in an interior space, reflections which also find an echo in 1931, "we still need to eat and drink", opined Dieckmann, as a comment on the futuristic visions of the day, continuing "and without love, life doesn't function either, and wherever there are small children, does it not often become very human?".17 And between love and the warmth of life of small children, "isn’t for most people sex the best form of well-being?"18

Contemporary questions of "warmth of life and sincerity" and "l’homme reste l’élément central" and well-being and the humane in domestic interiors that are ultimately what we are all striving for in our contemporary interiors. ¿Or what are your priorities? ¿Hygge???!?!?!?!!!

An Erich Dieckmann doesn't have all the answers, wasn't given the time to begin to formulate all the necessary questions, wasn't give the time to fully grow, and was, lest we forget, active in a society very, very different from ours; however, in that what he did, and why he did it and how he did it, an Erich Dieckmann can help us all approach our own answers for our age. Or put another, way through building better understandings of Erich Dieckmann we can also build better appreciations of how to build interior spaces "where human nature is allowed to flourish".

Chairs: Dieckmann! is a good place to start to lay those foundations. But can only be but a start, is but an invitation to begin......

Chairs: Dieckmann! The Forgotten Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann is scheduled to run at the Kunststiftung Sachsen-Anhalt, Neuwerk 11, 06108 Halle until Sunday March 27th

Full details can be found at www.kunststiftung-sachsen-anhalt.de

Sitting reconsidered. Design, Observe, Stage, is scheduled run at the Burg Galerie im Volkspark, Schleifweg 8a, 06114 Halle until Sunday March 20th.

Full details can be found at www.burg-halle.de/burg-galerie/

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

1Erich Dieckmann, Ist die Moderne Wohnungskunst nüchtern?, Das schöne Heim. Haus. Wohnung. Garten. Kunsthandwerk. Vol. 34, Nr. 8 Mai 1931, 260 - 263 (Vol 34 is also Vol 2 1930/31, there is also a very complicated relationship with the magazine Die Kunst who also appear to have published Ist die Moderne Wohnungskunst nüchtern?)

2Among the others relieved of their duties as part of the 1933 cost-saving measure one finds the likes of the ex-Bauhäusler Gerhard Marcks and Benita Koch-Otte, or the Modernist influenced bookbinder Dorothea Freise, and also Hans Wittwer who was a close associate of the second Bauhaus Director Hannes Meyer, and so, weirdly, those who who lost their jobs held avant-garde, non-völkisch positions.

3Aya Soika, Das Ehepaar Dieckmann im Nationalsozialismus, in Bursian et al [Eds.] Stuhle: Dieckmann! Der vergessene Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 2022

4ibid page 113

5Erich Dieckmann, Möbelbau in Holz, Rohr und Stahl, Die Baubücher, Band 11, Jukius Hoffmann Verlag, Stuttgart, 1931 available via https://www.digishelf.de/piresolver?id=1067053387 (accessed 16.02.2022)

6Otakar Máčel, Marcel Breuer und Erich Dieckmann - Ein Anfang, Zwei Karrieren, in Bursian et al [Eds.] Stuhle: Dieckmann! Der vergessene Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 2022, page 77

7Erich Dieckmann, Möbelbau in Holz, Rohr und Stahl, Die Baubücher, Band 11, Jukius Hoffmann Verlag, Stuttgart, 1931, page 69, available via https://www.digishelf.de/piresolver?id=1067053387 (accessed 16.02.2022)

8Charlotte Perriand, Wood or Metal, The Studio, Vol. 97, Nr. 433, April 1929, 278-279 And lest we forget Perriand did later recreate the steel tube chaise longue developed with Le Corbusier in bamboo. We all can, should?, change our positions with time.

9Otakar Máčel makes a brief comparison between some of Dieckmann's steel tube chairs and Gerrit T Rietveld's 1927 Beugelstoel, which on the one hand tends to reinforce Rietveld as a source of information for Dieckmann, but also poses the urgent question of where is Rietveld's Beugelstoel today, with its diagonals, cutting through the cube..... see Otakar Máčel, Marcel Breuer und Erich Dieckmann - Ein Anfang, Zwei Karrieren, in Bursian et al [Eds.] Stuhle: Dieckmann! Der vergessene Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 2022

10Its a very interesting comparison, and useful exercise, to place Dieckmann post-War in both West Germany and in East Germany and to consider the problems and opportunities he would have experienced and enjoyed in the two. And in which could he have been more successful......

11Erich Dieckmann Grundsätzliches zur Gestaltung moderner Kücheneinrichtungen, Reichsforschungsgesellschaft, Sonderhet Nr. 2, Die Küche der klein und mittelwohnung, Juni 1928

12The nature of German means there are an awful lot of German words that make perfect sense in German, but require paragraphs in English, Typenmöbel is a particularly good example, and can be considered a family of furniture objects with formal echoes that could be used in conjunction with one another rather than furnishing a space with the individual, independent, objects with no relation to one another as practiced by previous epochs, and so an important stepping stone in the development of interior design. The concept of Typenmöbel began in the early 20th century and was a popular approach in the 1920s.

13Erich Dieckmann, Ist die Moderne Wohnungskunst nüchtern? see FN 1 We're paraphrasing a little but don't believe inaccurately

14Tomás Maldonado, Rede zur Eröffnung des Studienjahres 1957/58, HfG Ulm, 03.10.1957 (HfG Archiv PA 656.2)

15Erich Dieckmann, Ist die Moderne Wohnungskunst nüchtern? see FN 1

16Verner Panton in Joe C. Colombo, Charles Eames, Fritz Eichler, Verner Panton, Roger Tallon: Qu’est ce que le design?, Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris, 1969 In 1969 language was still very male centred, let’s assume Panton meant homme in terms of people/humans/us all.

17Erich Dieckmann, Ist die Moderne Wohnungskunst nüchtern? see FN 1

18Verner Panton: Meine Design-Philosophie, BÜROszene, Vol 47, Nrs. 1–2, 1995