There are a great many and varied mediums via which to track the (hi)story of a region, the 2021 Bauhaus Lab chose plants; or more accurately, the 2021 Bauhaus Lab chose the (hi)stories of the flora in the region around Dessau as a medium for explorations of the human, social, industrial, political, economic, ecological, et al (hi)stories of the region.

A telling of a local (hi)stories which enables access to both global considerations on, and questions concerning, our relationships with the planet we require for our existence, and also to differentiated considerations on, and questions concerning, Bauhaus and International Modernism.

Considerations and questions presented in the showcase Vegetation Under Power – Heat, Breath, Growth in the Bauhaus Building, Dessau.

Celebrating its ninth edition in 2021, the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau's Bauhaus Lab brings international creatives of various hues together in Dessau for three months every summer to discuss, intervene with, reflect on and respond to a particular theme associated with "global modernism"; discussions, interventions, reflections and responses which always begin from an object.

Over the course of the preceding Bauhaus Lab's that object has been as diverse as, for example, Walter Gropius's desk; or the so-called India Lounge chair developed at the National Institute of Design Ahmedabad, India, by Hans Gugelot and Gajanan Upadhyay; or, and as we all remember, the small, metal, universal connector developed by Konrad Wachsmann and which became the central element in Wachsmann and Gropius's prefabricated construction system.

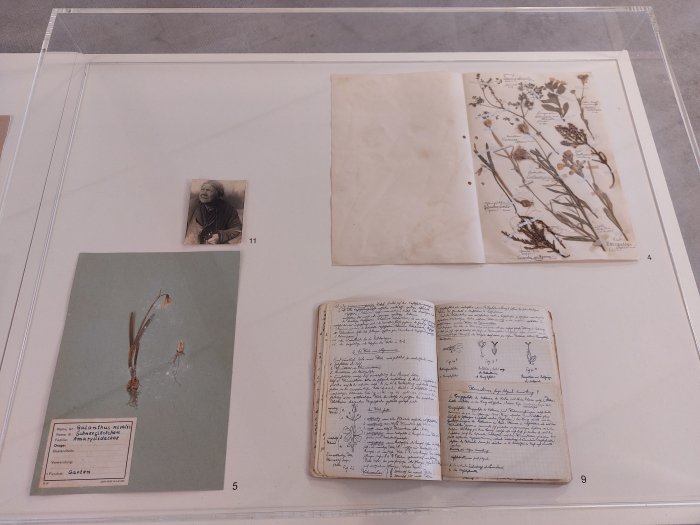

For the 2021 Bauhaus Lab the eight selected participants' journey began from a herbarium compiled in 1930 by the (then still student) botanist Hans Weber of flora from the Goitzsche riparian woodland area on the edge of Bitterfeld, near Dessau; or more accurately what in 1930 was the Goitzsche riparian woodland area, before in subsequent decades the increasing industrialisation of the region, and need for energy to power East Germany, saw the coal mining in the area that had began around 1900 dramatically expand, and saw the Goitzsche riparian woodland become one of the larger open-cast coal mines in East Germany. Which, no, didn't do a great deal for the local flora. Following the end of East Germany mining in and around Bitterfeld ceased and today, following a period of cleansing and re-naturalisation, the Goitzsche riparian woodland is a lake, the Großer Goitzschesee, one of several new lakes to have emerged in the area since the coal excavators were dismantled. Which, yes, has done a great deal for the local flora. If not necessarily the flora a Hans Weber would have collected in 1930.

And thus Goitzsche stands very representative for much of the (hi)story of the corner of Europe in which Dessau finds itself; or as Regina Bittner, head of the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau Academy, opined at the 2021 Bauhaus Lab Symposium, Hans Weber's Goitzscher herbarium exists as a silent witness to the transformation of the area around Dessau/Bitterfeld in the course of the 20th century.

A silent witness whose testimony the 2021 Bauhaus Lab employed as the basis for its explorations, for its discussions on, its interventions with, its reflections on, its responses to the entanglements, physical and metaphysical, of the natural, economic, industrial, social, floral et al (hi)stories of Dessau/Bitterfeld.

And which all are invited to explore, engage with, reflect on and discuss in Vegetation Under Power – Heat, Breath, Growth1

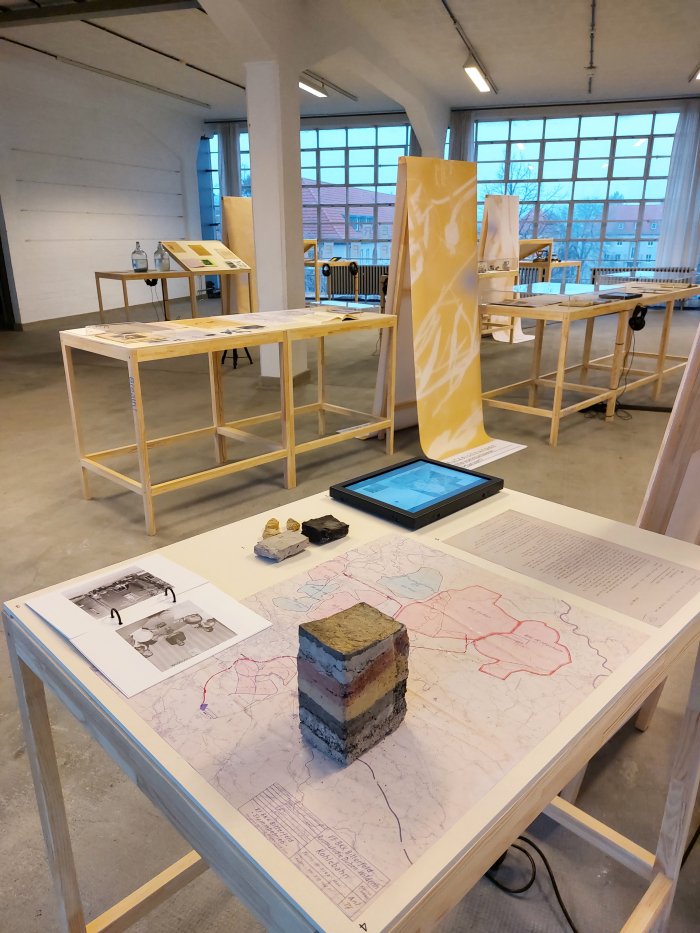

To that end Vegetation Under Power features 11 short chapters, 11 constellations to remain in the vocabulary of the Bauhaus Lab, which juxtapose the oft repeated Modernist mantra of Light, Air, Sun with the Heat, Breath, Growth of its title, and thereby link utopian visions with their slightly more dystopian realities, link the hopes for future society with the consequences we couldn't foresee, link human society with non-human societies, link the human environment with the the non-human environment, and in doing such allows, encourages, demands, one to pose questions on subjects as varied as, for example, how knowledge about the natural world is acquired, interpreted and disseminated, on the tangible and intangible networks on which human and non-human societies and environments rely, on the motivations of environmental activism, on the consequences of environmental activism, on geology as a physical and as a social discipline, on plants as more than food and fuel, on loss, revival, recreation, transformation, on.......

.......as a research and curatorial project the Bauhaus Lab doesn't produce answers, doesn't set itself objectives that could culminate in answers; rather as a platform it discusses, intervenes, reflects, responds.

Consequently the Bauhaus Lab exhibitions, rarely, present anything resembling an answer. So Vegetation Under Power, a modestly understated presentation that places responsibility for a large part of the exploration and inquisitiveness on its themes with the visitor. There are no explanations, no conclusions, no definitives. Which isn't a complaint, far from it: the presentation provides the nudges and stimuli, indicates themes and subjects that could be of interest, highlights aspects you may not have been aware of and/or hadn't considered in such contexts before, alters perspectives and associations, enables new paths to be laid, sets a framework. And then leaves you to reflect on the myriad subjects raised.

Including reflections on Bauhaus.

For all that the Bauhaus positions and ideals were conceptually fired by visions of a progressive, clean, equitable, better, world, a world of Light, Air, Sun and Hygiene, a world elegantly embodied in Walter Gropius's 1926 Bauhaus Dessau building with is vast curtain walls, unhindered open spaces, electric light bulbs and expansive ventilation concept; the buildings Bauhäusler constructed, including Gropius's 1926 Bauhaus Dessau building, were physically fired by coal. Lots and lots and lots of coal.2 The indication in Vegetation Under Power being that in the 1920s the Dessau Bauhaus building burnt its way through some 30 tons of coal a week.3 Which is an awful lot of smoke, fine particles, CO2, warm air, and vast gaping holes, ruptures, in the region around Dessau to enable the rapid, cheap, harvesting of the brown gold Bauhaus required. Which isn't to say the problems of open-cast mining and burning coal were all Bauhaus's fault, they clearly weren't; but is to say that while Bauhaus contributed but little to daily 1920s life in and around Dessau, it did contribute directly to the appalling air the people of 1920s Dessau had to breath.

And continued to breath post-War: in the 1970s some 2.5 tons of briquettes were delivered to the Bauhaus building every day, and because that wasn't enough, some 400 tons were permanently stored, piled, next to the Bauhaus building.4 Which means that when the East German authorities formally recognised Bauhaus in 1976, one of the most immediate symbols of Bauhaus stood next to one of the most immediate symbols of the negative environmental and social impacts of energy supply.5 And only very few in 1976 would have spotted the glaring contradiction. Or spotted it in 2021; because Bauhaus today is popularly associated with progress, cleanliness, equitableness, with Light, Air, Sun, no-one reflecting all too long on any possible negatives. Vegetation Under Power helps contextualise that impression.

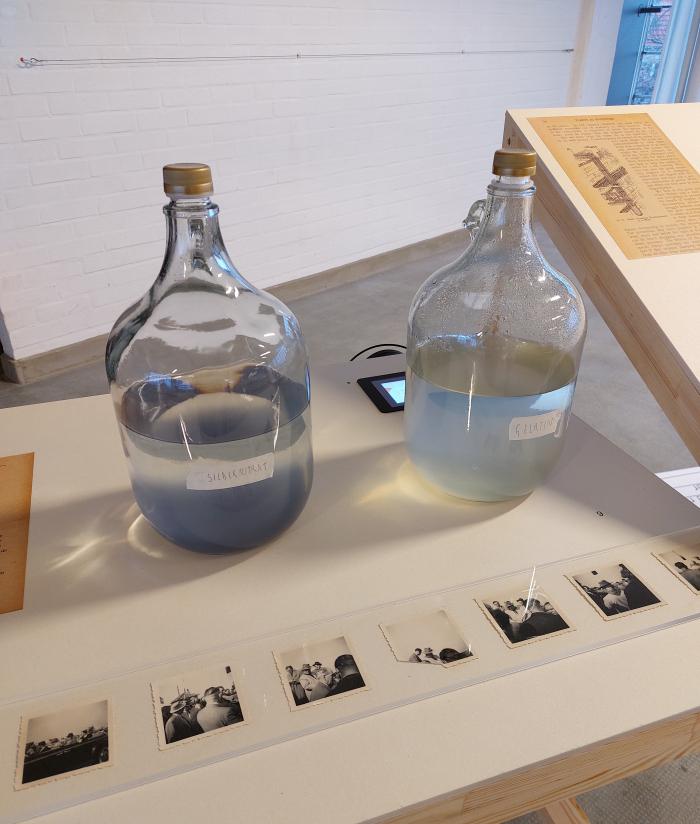

A contextualising of Bauhaus as simultaneously sooty smoke and spotless white facades, as simultaneously building new communities while around it established communities were bulldozed for its coal supply6, which helps lead one into further considerations on Bauhaus and their inter-War Modernist ilk's associations with the developments of contemporary industries, for all industries which promised the progressive, clean, equitable, better, world the Modernists envisaged, a brave new world riding in on a wave of new industrial possibilities under the guidance of rational designers. Industries such as the chemical industry in its various guises, a chemical industry which arose in and around Bitterfeld in the first decade of the 20th century, becoming over the early decades of the 20th century the dominant industry in and around Bitterfeld; a chemical industry understood not only in the 1920s as the future, but also understood as the future in post-War East Germany, or as a 1958 conference organised by the ruling SED announced "Chemie gibt Brot, Wohlstand, Schönheit", "Chemistry gives us bread, prosperity, beauty". And a chemical industry which, in combination with the local open-cast coal mining and power stations, meant that by the end of the DDR the region around Bitterfeld, that corner of Europe from which Bauhaus strove to disseminate Light, Air, Sun, was one of the more polluted corners of Europe......

.........considerations which help underscore that 19th/20th century industrialisation brought with it both prosperity, and bread in the form of jobs, but also a whole lot of grotesque foulness7, was invasive in the natural environment and caused untold, fundamental, damage to the material fabric we inhabit; damage which once understood had to be slowly and expensively repaired, as best we could/can, an ongoing process.8 And, yes, we are now going to directly juxtapose the problems arising from the exciting new industries and new possibilities of the early 20th century, with our own digital, smart, technology, with A.I., and the question of what damage could such possibly do to the social fabric we inhabit? And the natural environment we inhabit. Smart digital technology and A.I. aren't particularly environmentally friendly, the clouds, for example, that store our data aren't the harmless fluffy white ones of a summer afternoon. We know, we know, its all brilliant, creates Brot, Wohlstand and Schönheit for all. But what lessons could we possibly learn from the negative social and environmental consequences of early 20th century industrialisation our forbearers didn't, couldn't, see coming? Didn't, couldn't, see coming because as a species we really aren't as clever as we imagine ourselves to be. What if we were to reflect a little deeper? Could we, just possibly, side-step some of the pitfalls, pun intended, that invariably line our path forward? Will we bother trying to extrapolate? Or simply delight in how much less we have to think thanks to algorithms and A.I. making all our decisions for us, and also helping us optimise our lives, that other great, faultless, credo of the 1920s.

And don't get us started on delivery drones and flying cars........ And who actually needs their groceries delivered in ten minutes? Who?!?!

A thematically expansive, though tightly integrated, showcase Vegetation Under Power makes good use of the free, open, space of Gropius's Bauhaus building to allow you the space to work your way through the mix of documents, maps, photographs, plants, etc, and also original works developed by the eight Bauhaus Lab 2021 protagonists in the course of their research, and thereby allows you the space to approach differentiated appreciations of, for example, the changing understandings of the natural world in the course of the 20th century, a shift from a time when nature was seen as a passive, and free, raw material to understandings of nature as an active component in the inter-related networks and systems on which we depend and whose participation has a real value; understandings you very much get the feeling will continue to develop as we progress through the 21st century, and the 22nd, assuming we get that far.

Or on conservation, on the what we are conserving, the why we are conserving it, the how we are conserving it, and the if we should be conserving it, is it not after all continuously evolving nature?, questions which, yes, do bring one back to a Lucius Burckhardt; on the social and cultural impact of big industry, on the complex relationships between the needs of employees for not only work but for healthy food, leisure and community, and the needs of industry for space and resources and profit, which, yes, does bring one back to an Émile Zola, and to our contemporary digital industries. And also allows for reflections on East Germany, that period which, if one ignores the longer geological history, forms the largest component of Vegetation Under Power's considerations, and an East Germany which is present in various and varied forms, including Article 15 of the East German constitution from April 6th 1968, Paragraph 1 of which notes "the soil of the German Democratic Republic is one of its most precious natural resources", Paragraph 2 adding, "in the interests of the well-being of the citizens, the state and society ensure that nature is protected".

Discuss......?

Or just laugh out loud. And then cry when you realise they weren't alone in their hollow pretence, and how little has changed globally since.

But for all Vegetation Under Power is an indirect, abstracted, tour of Goitzsche from riparian woodland to open-cast coal mine to lake which allows one to approach more nuanced understandings of the complex, inter-related, shifting, evolving, natural and social, tangible and intangible, understood and as yet unidentified, systems and networks on which we all depend. And for which we thus all, collectively and individually, must accept responsibility. The question is how? And no, there isn't an app for that.

Bauhaus Lab: Vegetation Under Power – Heat, Breath, Growth is scheduled to run at Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Bauhaus Building, Gropiusallee 38, 06846 Dessau-Roßlau until Sunday February 20th.

Full details can be found at www.bauhaus-dessau.de/vegetation under power

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

1Traditionally a book is published alongside the Bauhaus Lab exhibition in which the themes and positions arising are presented in more detail. Current problems in international publishing mean as of today no Vegetation Under Power book is available, we will update when that changes.......

2There are obviously a lot of jokes you Germanophones out there could make about Bauhaus's famed Kohleknappheit, ewig Kohleproblemen or the Verbrennen von Kohle at Bauhaus, but we'll leave those to you....

3Number not explicitly noted in the exhibition but is very much implied in a wall text which takes as its basis the 1994 installation "Spur der Kohlen" by Oliver Blomeier and also the book Monika Markgraf, Archäologie der Moderne. Denkmalpflege Bauhaus Dessau, Jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2021

4Numbers noted in a wall text which takes as its basis the 1994 installation "Spur der Kohlen" by Oliver Blomeier and also the book Monika Markgraf, Archäologie der Moderne. Denkmalpflege Bauhaus Dessau, Jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2021

5One must note that Gropius's Bauhaus building was damaged in an aerial attack on Dessau in 1945, as a consequence of which it burnt down, and in 1976 was still, largely, a War ruin, or more accurately a roughly patched up War ruin that bore but only little resemblance to what it was in 1926. Or 2021. And one must also add that we never personally experienced, nor have we ever seen a photo of, the coal heap next to the building, thus are unsure how direct the juxtapose would have been in 1976. Thus the comparison is perhaps more a rhetorical vehicle than an actual fact.....

6As far as we are aware no villages were bulldozed in the 1920s, that came later, again its more a rhetorical vehicle than an actual fact.....

7A recurring, and very apposite, example in the exhibition is the photographic film production that was practised in Wolfen, now part of Bitterfeld-Wolfen, since 1909 and which required in the factory the highest standards of cleanliness and purity, lest the smallest fleck of dust should land on the film, while outside was, when not exactly a toxic swamp, was, in relation to the interior, a toxic swamp. And air that was primarily impurities. But as they were landing in people's lungs and not on photographic film, that was OK......

8There is still a sizeable chemical industry in Bitterfeld, but clearly operating to different standards than in the past. Which is arguably part of the restorative process, the accepting that the rules by which the industry previously operated were insufficient and needed strengthening in the interests of individuals, wider society and the natural environment.... which, yes, one can pleasingly extrapolate to considerations on the rules by which digital technology and A.I. and delivery drones and data protection currently operate, and questions of how we'll look back on our contemporary rules from 2080.......Assuming that is we're still here in 2080........