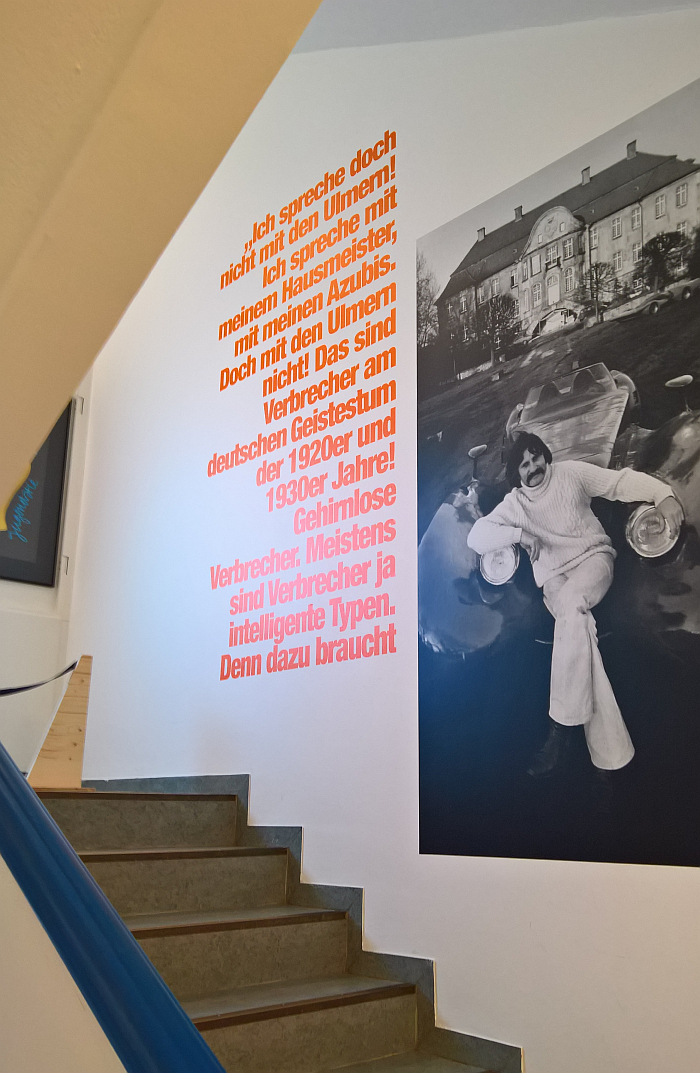

In context of the exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau, the Bröhan-Museum Berlin's staircase is emblazoned with a long quote from Colani, a long and typically outspoken quote, in which Luigi Colani denigrates the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, that design school which has such a prominent and pre-eminent position in popular understandings of design in post-War West Germany; and who for Luigi Colani were "defrauders of the German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties! Imbecilic criminals."1

A quote that not only neatly epitomises the (consciously cultivated) Colani communication strategy, nor only leads one to reflect on Colani's own relationship to inter-War design in Germany, but for all leads one by necessity to question the validity of the accusation; and thereby to reflect on the relationship(s) between the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm and the "German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties", and by extrapolation to reflect on post-War design in West Germany........

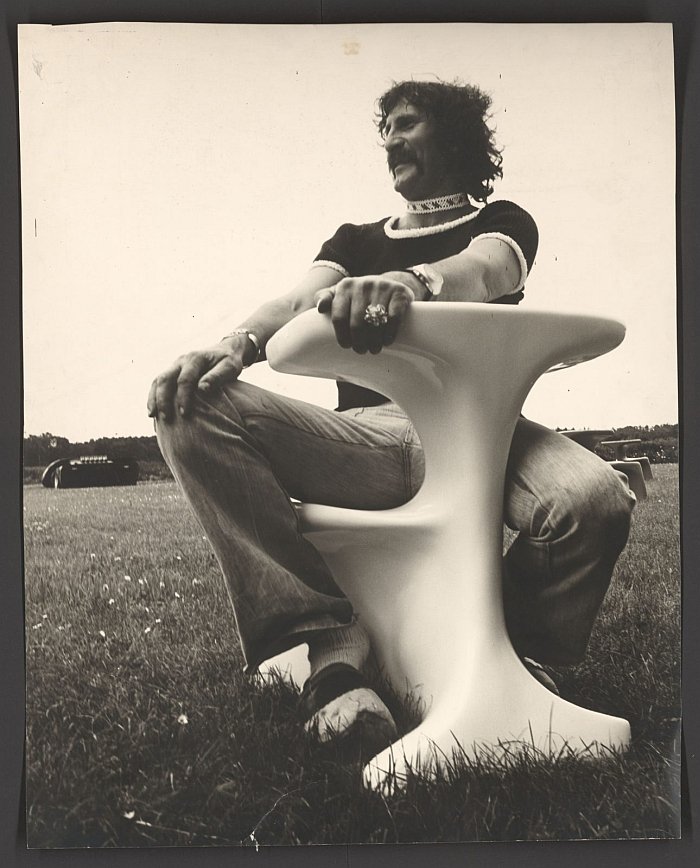

Born in Berlin on August 2nd 1928 Lutz "Luigi" Colani was, we don't feel it over-exaggerated to claim, one of the more colourful figures in post-War West German design: literally and figuratively. That we discussed and reflected on the Colani biography and oeuvre in context of the exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau, we refer you there dear reader for wider considerations, and focus here on Colani's denigration of the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, and their, alleged, crimes against the "German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties".

A period when Germany was, without question, one of the motors of creativity in Europe, and the World; innumerable, and diverse, German based artists, architects, designers, critics and manufacturers, contributing to the development and dissemination of new ideas and understandings. If a contribution that today is all too often reduced to Bauhaus.

A reduction Luigi Colani makes, his "German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties" being essentially a synonym for Bauhaus.

And his denigration of the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm being largely a component of his wider criticism of the post-War reception of Bauhaus. A criticism Colani succinctly elucidates in a 2011 video interview which runs on constant loop in Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau2, and which in doing so drives itself into the deepest recesses of your consciousness, and which can be paraphrased thus: whereas Bauhaus, certainly in its early Weimar years, was the red square, blue circle and yellow triangle, a geometric understanding and for all a geometric understanding in bright colours, something that Colani sees confirmed in Wassily Kandinsky's 1925 painting Gelb-Rot-Blau [Yellow-Red-Blue], a work Colani refers to as a form of Bauhaus "testament", post-War Bauhaus loses the circle, loses the triangle, loses the bright colours, "Bauhaus was now square, cubic, steel, glass and grey".3 A statement it is difficult to argue against, and a state of affairs that Colani refers to as a "Testamentsfälschung"4, a falsification of the Bauhaus testament, a faking of the Bauhaus legacy, and one, for Colani, deliberately and wilfully propagated and disseminated by West German industry.

And amongst the worst offenders being for Colani the "Alles-Eckig-Macher"5, the all-things-angular-makers, the quadratists, at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm.

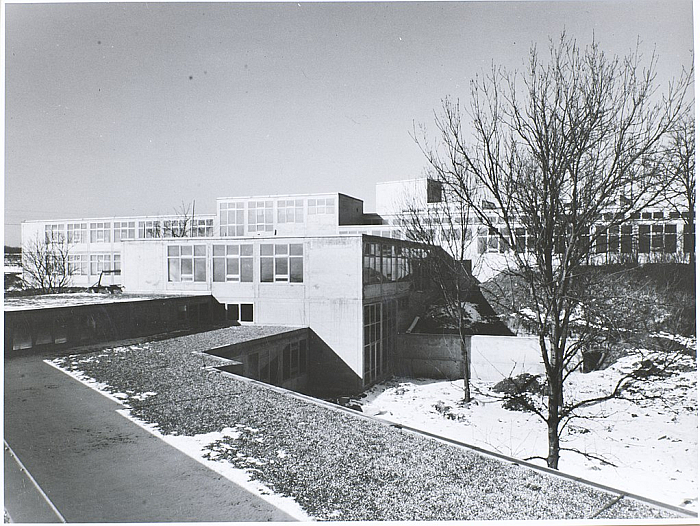

Established in 1953 the Hochschule für Gestaltung, HfG, Ulm can be, and regularly is, considered the official unofficial Bauhaus successor institute, and was very nearly the official official Bauhaus successor institute: Walter Gropius offering the school's initiators the use of the title "bauhaus ulm".6 An offer they rejected. Not least because they understood fundamental differences between the HfG Ulm and the Bauhauses.

Or more accurately put, some of the initiators did.

Here isn't the time nor place for a full discussion on the (hi)story of the HfG Ulm; but is the time and place to note that the HfG Ulm's founding Rector was the Swiss architect, sculptor and Bauhäusler Max Bill, and that the early teaching staff included Bauhäusler such as, and amongst others, Josef Albers, Johannes Itten and Helene Nonné-Schmidt, and thus was an institute where the colour and geometry of Bauhaus Weimar was very present. However, following disagreements on the structure of the teaching, the content of the syllabus, and pretty much everything else, disagreements not least between Max Bill and his fellow co-founder Otl Aicher, Bill resigned as Rector in 1956 and the leadership of the school was taken on by a board whose members (initially) included, alongside Aicher, the likes Tomás Maldonado and Hans Gugelot. The departure of Bill also ending Albers, Itten and Nonné-Schmidt's associations with the institute and seeing it begin to move conceptually ever further away from Bauhaus, and thereby become the HfG Ulm rather than bauhaus ulm.7

And move towards the quadratic and the monochrome? Into a world falsification and criminality?

Restrictions of time and space, and for all restrictions through closed libraries, prevent an exhaustive discussion at this juncture, prevent us allowing all relevant protagonists to have their say8; however, in the person of Otl Aicher one has not only a key figure in the establishment of the HfG Ulm and a man who in many regards symbolises the HfG Ulm, but also a man who reflected a lot on Bauhaus, both in its inter-War existences and its post-War reception and relevance, and who also reflected a lot on the Bauhauses in relation to the HfG Ulm.

And who thus is well placed to respond to Luigi Colani's criticism/denigration.

Born in Ulm on May 13th 1922 Otto "Otl" Aicher began studying sculpture at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste Munich in 1946, but quickly left as the juxtaposition between the Akademie and reality became all to clear to him, or as he later phrased it, "we returned from the war and the Akademie wanted us to consider aesthetics for the sake of aesthetics. That was no longer viable ... was, we asked ourselves, a culture and an art that ignored the real human problems of a post-War era not exposing, denouncing, themselves? ... what, in our opinion, was important was not to enrich art with a few more works, but to demonstrate that culture today must have life as a whole as its theme ... we were interested in the design of daily life and the human environment, in the products of industry, the behaviour of society."9

And thus a position that reminds very much of Mart Stam during his, all too brief, tenures in post-War East Germany, and, for example, his comments in 1949 during his Inaugural Address in Dresden, that "we understand that art should no longer be a pleasant entertainment for a few preferred connoisseurs, but that art has the task of making the life of all working people – men, women and children, deeper and richer. .... the few, one-off, artistic moments say little about the standard of living of a people – rather the hundreds of objects and customs of daily routine are the eloquent witnesses of the cultural niveau of a people and their time".10 Whereby Stam's position was, arguably, a little more politically based and informed than Aicher's. But we digress...... here isn't about comparing Otl Aicher and Mart Stam, although that is well worth doing, nor about comparing the HfG Ulm and the from Stam established Institute for industrielle Gestaltung in East Berlin, although that is also well worth doing, but about Aicher, Colani, the HfG Ulm and Bauhaus.

The later being for Otl Aicher an institute that despite its numerous shifts and incarnations over the 14 years of its existence "didn't make the leap away from art. On the contrary. The real powers at Bauhaus were the painters. Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger and Schlemmer"11, and a primacy of art that Otl Aicher understood as "a threat to design", that for him "design should develop its results from the object. The danger was that design would become an applied art with its solutions borrowed from art."12

Whereby the word "become" is interesting, because at that time it still largely was; pre-1940s design was (primarily) self-evidently applied art and a great many, the greater many?, early 20th century designers were artists.13

Design in the sense it is understood today is, largely, a post-1940s discipline; and while objects have always been "designed" i.e. formed, and while in the early decades of the 20th century individuals began increasingly to reflect on the hows, whys and wherefores of the form of our objects of daily use, to form on a more considered, functional, basis than the primarily decorative of decades past, it wasn't until the second half of the 20th century that "design" and the "designer" arose as we understand the terms today.

And arose, so Otl Aicher, largely despite Bauhaus, "Walter Gropius kept Bauhaus open to the profane, for buildings, tables, chairs and furniture, but not as such, but as elements of a new faith. The painters found these in elementary geometry, in the square, in the triangle, in the circle and the primary colours red, yellow, blue, black and white. Thus the conflict was programmed: is design an applied art, does it appear in the elements square, triangle and circle, or is it a discipline that draws its criteria from the task, from use, from production and technology? Is the world the individual and tangible, or is it the general and abstract? Bauhaus did not and could not resolve this conflict as long as the term art was not freed from taboos, as long as one clung to an uncritical Platonism of pure forms as world principles."14

For Aicher, so can one extrapolate, the HfG Ulm freed art from taboos, freed itself from "pure forms as world principles" and understood design as "a discipline that draws its criteria from the task, from use, from production and technology" rather than "in elementary geometry, in the square, in the triangle, in the circle". One of several very clear rejections Otl Aicher makes of an aesthetic approach to design, of a strictly formal approach to design. A rejection of not just the circle and triangle, but of the square as means in themselves.15 And of a very clear separation between the artists at the Bauhauses and the designers in Ulm.

And if we accept Aicher's argument, which you don't have to, but for the sake of the discussion it would be helpful if you didn't overly contradict it, at least not yet; and so if we accept Aicher's argument, then one approaches an understanding that the HfG Ulm undertook a, for them, necessary realignment of the "German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties", took a focus on criteria such as, for example, technical functionality, industrial production, formal reduction, new materials that became established within the Bauhauses, and approached them from different perspectives, approached them in context of a design process rather than an art process, and thereby far from copying, and in doing so defrauding, the creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties, took that spirit in a new direction.

And while some objects created by staff, students and alumni of the HfG Ulm are/were unquestionably quadratic, the Ulmer Hocker being a particularly apposite case in point; when that was the case, then for reasons other than pure formal aesthetics, for reasons developed from the task/object, rather than from "an uncritical Platonism of pure forms".

And if we accept that, and again you don't have to, but it would be helpful if you at last went with it for the sake of the discussion; if we accept that, where does that leave Luigi Colani's criticism of the HfG Ulm?

Where Luigi Colani's criticism is always to be found, in the provocative.

There is an argument to be made that successful as Luigi Colani was as a designer, the Luigi Colani brand was bigger, arguably more profitable, than the Luigi Colani commercial product portfolio; that while Colani developed a great many interesting and important projects, and unquestionably contributed to the development of design understandings, keeping the Luigi Colani brand in public focus was a task every bit as important as actually designing actual products. And then, as now, there is no simpler way to remain in the focus of public attention than via a well-considered and appropriately timed provocative statement; and Luigi Colani, inarguably, mastered such better than anyone else in post-War design.16 In Germany or anywhere. In neigh on every interview he ever gave, and every article he wrote, he not only unashamedly applauds his own talents but attacks, denigrates, insults the work of others. Something neatly illustrated by his late 1970s altercation with the West German office furniture industry of whom in 1977 Colani opined, "as with architecture, the office furniture scene has become a stomping ground for the worst of inhuman mediocrity", before going on to outline the, for him, numerous faults and failings of the industry, not least their ongoing ignoring of the contribution of office furniture to "seating related injuries and tendinitis", adding, "I no longer believe in an industry that bypasses people and their needs in such a disorderly, hypocritical, manner as the furniture and office furniture troupes", and demanding a strike by consumers: "refuse to buy office furniture for only a few months. These gentlemen will then crawl on their knees to the customer, but this time to ask them what they need."17 An article that invariably generated a heated response from designers and manufacturers, and which saw the Schwarzwald based manufacturer Interstuhl issue a "call on German industry of all branches ... to boycott Herrn Colani"18 on account of his unending tirades; a boycott call to which Colani responded in, what we believe is referred to today as, a typically robust fashion, i.e. more insults.19 And a boycott call that Colani later cited as a contributing factor to his decision in the early 1980s to relocate to Japan.20

Which doesn't mean that Luigi Colani didn't and doesn't have interesting contributions to make to the design discourse, he did and does; is to say one shouldn't be distracted by the more outrageous statements, rather to understand them as deliberate provocations, often the over simplifications so beloved of provocateurs, sometimes just the out and out insults beloved of provocateurs, sometimes simply wrong. And which very often, despite being such, are also statements which can be stimuli for more reasoned, objective, reflection.

Including the aforementioned reflections on Colani's own relationship to inter-War design in Germany, his own relationship to the "German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties".

In the aforementioned video interview Luigi Colani claims that while everyone else has reduced Bauhaus down to the quadratic monochrome, are, as he phrases it, making use of only one third of Bauhaus, he makes use of the two thirds of Bauhaus everyone else ignores. Except he doesn't. OK the bright colours, we'll give him that, but not the geometric forms; rather Colani's work, as the exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau neatly elucidates, is notably ageometric, anti-geometric even, that a key difference between Colani and his contemporaries is less in his use of the two thirds of Bauhaus everyone else ignores, but in his rejection of the one third, the quadratic, he understands everyone else as using. And Colani himself also ignores the other two thirds. Much more Luigi Colani makes use of free-flowing, biomorphic, curves, his understandings being largely informed by the free-flowing florid of French Art Nouveau, a formal understanding and expression that Bauhaus and their ilk sought to remove from our objects of daily use, sought to transform into rationalised geometric forms. And a reference to French Art Nouveau that roots, pun intended, Colani's work much more in the creative spirituality of the noughties and tens, than the twenties and thirties.

And while that would appear to place Luigi Colani's work as applied art, and certainly Colani was keen to underscore that he had initially studied sculpture, was a highly gifted sculptor - obviously - and thought like a highly gifted sculptor; if we return to Otl Aicher and Bauhaus, then one can also understand Luigi Colani, through his focus on aspects such as, and amongst others, ergonomics, tactility or organicity, as a creative who freed art from taboos, freed himself from "pure forms as world principles" and as someone who understood design as "a discipline that draws its criteria from the task, from use, from production and technology" rather than "in elementary geometry, in the square, in the triangle, in the circle". As a designer in a post-1940s understanding, and as a creative "interested in the design of daily life and the human environment, in the products of industry, the behaviour of society."

And thus, much as Otl Aicher understood the HfG Ulm as a recontextualising of that which had been propagated and developed in the inter-War years, if one so will, a necessary realignment of the twenties and thirties, so can Luigi Colani's work be understood less as a continuation of the creative spirituality of Bauhaus, and more as an alternative development, if one so will, a necessary realignment, of that spirit. That despite what he may claim, Luigi Colani didn't use the missing two-thirds of Bauhaus, wasn't honouring Kandinsky's Bauhaus testament, but rather took a step back from the twenties and thirties and transformed the decoration of Art Nouveau not to the rational geometric as Bauhaus et al had done, but to a functional component.

Where Luigi Colani can be considered a continuation of the spirit of the twenties and thirties is, we'd argue, his understanding that "Bauhaus itself had questioned everything"21, as indeed did Luigi Colani. As did Otl Aicher. As did the HfG Ulm.

Consequently, an argument can be made that neither Luigi Colani nor the HfG Ulm represent either a continuation nor a defrauding of the "the German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties", but rather represent two alternative understandings of how to progress from that creative spirituality; different answers to questions concerning the objects of our daily use, to questions concerning our domestic and work environments, to questions on how to transpose and translate understandings of materials, technology, production, standardisation et al of twenties and thirties into design processes, how to develop applied art into design with the object, use and user as the focus rather than the aesthetic.

And thus Luigi Colani could have served as a Professor at the HfG Ulm?

We wouldn't go that far.

There are many other aspects to be considered, here is but a snapshot of a wider discussion.

And in any case one of more interesting points in Luigi Colani's oft repeated criticism of the HfG Ulm is that the institution closed in 1968, and thus, more or less, at the very moment Colani moved decisively from the vehicle design with which he had established his reputation, to furniture design.22 What he was railing against was no longer existent as an institution, was a historical moment, an artefact, and thus much as Colani's "German creative spirituality of the twenties and thirties" is a synonym for Bauhaus, "HfG Ulm" can be understood as a Colani synonym for the design environment of 1970s West Germany, a design understanding "Ulmer Prägung", "Ulm influenced/embossed"23, as Colani once disparagingly referred to it. And specifically a synonym for the 1970s West German furniture design environment, one in which, despite critical approval, Luigi Colani enjoyed only very little commercial success; the vast majority of his concepts and products never finding their way into commercial production, or when they did, then not for long. A state of affairs arguably on the one hand associated with Colani's manner, on the hand other associated with Colani's manner, and on the third hand associated with Colani's manner; his 1977 tirade against the West German office furniture industry was very clearly a consequence of the rejection of one of his concepts by the Ahlen based manufacturer Comforto. And one can't help thinking that had he pursued an alternative strategy he could have either changed Comforto's mind, or found a different partner. But he didn't. Because he was Luigi Colani.

In addition one could, can?, argue that many of Colani's designs were genuinely ahead of their time. One of the mistakes often made when looking back over the (hi)story of furniture design is to understand works/concepts which are popular today as being popular when they first appeared, which is rarely the case, there is invariably a lag, steel tube cantilever chairs being an excellent case in point, and similarly a lot of the experimental, biomorphic, free-form plastic furniture of the 1970s: yes there was a market then, but there is arguably a much, much greater, and for all broader, more mainstream, market now. Something one can understand as much in a Verner Panton as in a Luigi Colani; and we'd argue many of the objects Colani struggled to place with manufacturers, or establish in the market, in the 1970s would fly off the shelves today.

And, arguably, we never asked him, but given the chance would have, by way of seeking to strike against an industry and market that didn't, wouldn't, couldn't understand and facilitate him, Colani, deliberately and proactively, made the HfG Ulm a scapegoat24, one who could no longer answer for itself, but who enjoyed a prominent and pre-eminent position in the design environment of 1970s West Germany, was still fêted by a great many, and was thus an easy, obvious, target. And a symbolic target, of the kind provocateurs so often choose.

And importantly, one which, because it was itself closed, could be attacked without automatically closing other doors to Colani, still allowed him outlets for his work.

Or put another way, for all the prominence and pre-eminence of the HfG Ulm in post-War design in West Germany, it wasn't the only actor, nor necessarily the leading, and was no longer in existence, unlike other important actors of the period, and we can find no occasions where Luigi Colani attacked, for example, the Deutsche Werkbund who post-War pushed, pushed, and kept on pushing, the gutes Form mantra whose reduced formal expression stands so opposed to that of a Luigi Colani. Similarly we can find no criticism by Colani of the Rat für Formgebung, the German Design Council25; and indeed criticism of both the Rat für Formgebung and the Deutsche Werkbund would in many regards first come with the Postmodern orientated Neues deutsches Design of the 1980s, and who in doing so rejected, and sought to emancipate design from, the established furniture design industry. An industry Colani was, despite all his criticisms, keen to work with. And did work with. On his terms, obviously.

And which if so would tend to further underscore that the HfG Ulm wasn't an institution Luigi Colani had reflected long and in-depth upon, but rather was an easy symbolic target in context of the (consciously cultivated) Colani communication strategy.

Which if so, would be a great shame.

"I don't talk with the Ulmer!"26 begins Colani's denigration of the HfG Ulm on the Bröhan-Museum Berlin's staircase; yet with only the briefest of reflections, that sounds like a mistake. On the one hand because discourse is the essential basis of all social and cultural development, we can't progress if we don't talk to one another. And on the other, and for all the myriad formal and expressive differences between many an Ulmer and Colani, they shared a lot of similarities: both, for example, understood that objects must be responsive to not just the user but the nature of their use; both placed a high value on ergonomics; both sought a clarity in the form language; both understood industrial production as more than a tool to maximising profits; both understood form as a component of function rather than dependent on it; both understood design as a cultural exercise; both understood design's social relationships; both understood the designer as having a responsibility, a responsibility that went beyond the objects as such, "the designer must be a social critic who demands reform" opined in 1969 ................ Luigi Colani.27 A statement that just as easily could have been attributed to Otl Aicher. And just as easily emblazoned the staircase at the HfG Ulm.

Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau runs at the Bröhan-Museum, Schlossstraße 1a, 14059 Berlin until Sunday August 29th. Full details, including videos, can be found at www.broehan-museum.de, in additon there is a bi-lingual German/English digital guide to the exhibition with numerous texts and objects.

1Luigi Colani, "Ich beschäftige mich mit der dritten Dimension von Anfang an als Bildhauer." www.baunetz-id.de (https://www.baunetz-id.de/menschen/luigi-colani-11846579 accessed 19.02.2021) Colani speaks of the "German Geistestum of the twenties and thirties", Geistestum has no easy translation into english, but is most normally translated as spirituality, although Geist is more than spirit in a religious/moral/ethical sense, and more or less freely interpretable depending on context, thus we added "creative" as that is what is without question implied.

2The interview itself is not publicly available, but Colani referred to Gelb-Rot-Blau as a Bauhaus Testament on many occasions. If it actually is, is another question.....

3Luigi Colani, Bio-Industrie-Design: Herausforderungen und Visionen, in Grote K.-H. and Feldhausen J. [Eds] Dubbel: Taschenbuch für den Maschinenbau, 23., neu bearbeitete und erweitere Auflage, Springer 2011, page F50 He makes the same argument with other words in the video.

4ibid, in the video in Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau he also uses the term "Testamentsfälschung"

5Luigi Colani, "Ich beschäftige mich mit der dritten Dimension von Anfang an als Bildhauer." www.baunetz-id.de (https://www.baunetz-id.de/menschen/luigi-colani-11846579 accessed 19.02.2021)

6Otl Aicher, Bauhaus und Ulm, in Otl Aicher, Die Welt als Entwurf, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 2015 page 86

7Whereby, if one considers, as we do, that Bauhaus Weimar and Bauhaus Dessau were different institutions, then one can argue that the HfG Ulm can be/was Bauhaus Ulm i.e. a further development of the path from Weimar over Dessau.... (As Bauhaus Berlin, essentially, never fully opened it's hard place it on that path....)

8And logically means that we can present here but a snapshot of what is and was the HfG Ulm, and certainly not a truth. A slightly different take can be found in our post from the exhibition Hans Gugelot. The Architecture of Design at the HfG-Archiv, Ulm

9Otl Aicher, Bauhaus und Ulm, in Otl Aicher, Die Welt als Entwurf, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 2015 page 86ff

10Antrittsrede, in Herman van Bergeijk & Otakar Máčel [Eds.] Teksten van Mart Stam, Sun, Nijmegen, 1999 Page 135ff

11Otl Aicher, Bauhaus und Ulm, in Otl Aicher, Die Welt als Entwurf, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 2015 page 89

12ibid page 88

13And not just amongst the Bauhäusler, while many early 20th century designers such as, for examle, Richard Riemerschmid or Peter Behrens were/are popularly known as architects they had no formal architectural training, but rather were trained artists.

14Otl Aicher, Bauhaus und Ulm, in Otl Aicher, Die Welt als Entwurf, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, 2015 page 90

15Colour, the use of colour and understandings of colour was also important to Otl Aicher, he was after all principally and graphic and corporate designer, but Aicher and colour is a discussion for another day, here our focus is form.

16It is also worth noting that Luigi Colani was regularly booked as a speaker for conferences, seminars, etc... and that one presumes because the organisers knew he'd be controversial and therefore have a PR effect. And we suspect Colani would have been well paid for such speeches, and so needed the carefully and continually maintained outspoken profile...

17Luigi Colani, über Büro-Design. Aufruf zum Warnstreik, Wirtschaftswoche Vol 31, Nr 43 14.10.1977 page 50

18see Form 81, 1978 page 54 The implication in Form is that the boycott call was originally made in a letter to Wirtschaftswoche, but we can't locate it, which doesn't mean it wasn't, just that we possibly keep missing it. Or it was made somewhere else/ in some other context. Form do however quote Interstuhl at length.

19Rangeleien mit und um Colani, Form 82, 1978 page 82

20see, for example, Luigi Colani, "Ich beschäftige mich mit der dritten Dimension von Anfang an als Bildhauer." www.baunetz-id.de (https://www.baunetz-id.de/menschen/luigi-colani-11846579 accessed 19.02.2021) One must also note that by the late 1970s Colani had largely failed to establish himself as a furniture design in Europe, and was, one presumes, seeking new perspectives. And, as he oft notes, his understandings are more in tune with Japanese thinking see, for example, https://web.archive.org/web/20180909221950/http://www.bangertinternational.de/colani_interview.html (accessed 19.02.2021)

21Interview with Luigi Colani, Experiment 70. Designvisionen von Luigi Colani und Günter Beltzig, Almut Grunewald and Tobias Hoffmann [Eds.], Museum für Konkrete Kunst Ingolstadt, 2002

22In the Colani biography dates are regularly difficult to assign with any great certainty; however, according to colani.ch, which may or may not be an official Colani website, for its barely a website, in 1965 Colani achieved "World-wide success with furniture design: Asko, Fritz-Hansen, Cor, Kusch+Co.", which he didn't, although he did cooperate with them all, but does sound like Colani and so 1965 could mark the start of his cooperations. Current restrictions obviously hamper detailed research but the first reference to Luigi Colani we can find in the magazine Form, one of the more official official West German design publications is in Form 41, March 1968, as part of a review of the 1968 Cologne Furniture Fair, where Colani and Kusch+Co presented a concept featuring chairs formed from ABS plastic and which weren't free-standing but rather leant against one another to form rows, and were stackable, @ 200 per vertical metre. On the same pages one finds Verner Panton's moulded plywood S chair for Thonet and the "Verner Panton stackable chair" i.e. the Panton Chair "for Herman Miller" sshhhh!! don't tell Vitra.....

23Mit dem Molotow-Cocktail in der Tasche.... Ein gespräch mit Luigi Colani, Form 48, Dezember 1969 page 14

24It is important to note Colani often railed against West Germany design schools in general, and for all against West German design professors, and arguably part of his focus on the HfG Ulm was based on an understanding of the school as being a prototype of post-War West German design education. If it was and if so in how far, is a subject for another day

25Again on account of the many closed libraries, and general dfficulties of researching in the current realities, we might just not be finding them, they may very well exist and should we find any we will update. However Colani did have a habit of repeating the same accusations in varying forms, and so we would expect to find something somewhere....

26Luigi Colani, "Ich beschäftige mich mit der dritten Dimension von Anfang an als Bildhauer." www.baunetz-id.de (https://www.baunetz-id.de/menschen/luigi-colani-11846579 accessed 19.02.2021)

27Mit dem Molotow-Cocktail in der Tasche.... Ein gespräch mit Luigi Colani, Form 48, Dezember 1969 page 15