"The placing of foam mattresses, spring mattresses, and the like, on bed frames made of wood or metal is familiar", notes a July 1966 patent application, and it was. However, it continues, "bed frames of this type are heavy, continually take up one and the same space in a room, must be dismantled if they are to be moved to a new location, and represent a major obstacle in context of cleaning the bedroom."1

Which, certainly in the early 1960s, they were and did.

But what is one to do?

Verner Panton had an idea.

An idea that may not count amongst his better known projects, but is a project that allows one to approach a better understanding of the work and career of Verner Panton.......

Born on February 13th 1926 in Gamtofte on the Danish island of Fyn, Verner Panton studied architecture at Copenhagen's Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi, graduating in 1951, and when, and following the completion of a brief tenure in the office of Arne Jacobsen, he, literally, set out into the world: his VW camper van serving as home and studio as he undertook numerous tours through contemporary European architecture and design. And in which context his first designs arose. Just one of the many reasons why aligning Verner Panton with design from Denmark should be undertaken with extreme caution. And a lot of footnotes.

Settling in Basel in the early 1960s Verner Panton developed in the course of the subsequent decades a varied, international, career, a career which saw him move freely across, and amongst other arenas, textile design, lighting design, interior design and furniture design; the latter being that for which he is, arguably, best known today.

A popular furniture design career that began, at least professionally, during his time with Arne Jacobsen in Copenhagen, and, arguably, for reasons other than active choice; "I was put to making furniture, simply because I was the youngest and worst in the studio", he later recalled, we suspect with a sprightly self-deprecating glint in his eye, "that's what things were always like with Arne Jacobsen; he wouldn't use his good architects on that kind of thing."2

Alternatively one could argue that Arne Jacobsen knew exactly what he was doing, understood something in the young Verner that the young Verner still hadn't recognised, or that fate may have been resident in Copenhagen in the early 1950s; for the young architect Verner Panton developed into, arguably, one of the 20th century's most important and influential furniture designers.

If one, arguably, most popularly known for one furniture design in particular.

But no designer is their popularly known works alone. All are also their lesser known works.

Even a work as, apparently, unassuming as a bed pedestal.

The exact origins of the project we, we alone, and absolutely no-one else, are referring to as Skønseng3, are lost in the mists time; can however, with a little imagination be, when not reconstructed, then certainly imagined.

In 1962 Verner Panton launched an upholstered furniture collection with the German manufacturer Storz & Palmer, not his first upholstered furniture collection, if one of the very first; not his first collaboration with a German manufacturer, if one of the very first. But was the very first collaboration with German foam manufacturer Metzeler.

Established in 1863 by Robert Friedrich Metzeler as a rubber dealership in Munich, Metzeler quickly moved to the production of rubber goods; establishing in the 1870s a factory in Munich's Westend, and concentrating primarily on two fledgling forms of transportation: aviation, Metzeler developing rubber envelopes for hot air balloons/airships; and automotives, Metzeler developing and producing tyres for vehicles of all types and classes, primarily motorbike tyres.

In 1954 Metzeler expanded, almost literally, its portfolio, with the opening in Memmingen, southern Bavaria, of a foam rubber factory; a logical expansion, pun intended, of the company's range, and that with a material that was still very much in development, a development Metzeler are/were very closely involved with, and a material which today the company form into products for a myriad applications including mattresses and seating upholstery.

Seating upholstery which brings us back to the 1962 Storz & Palmer collection, a collection in context of which Metzeler were responsible for the development of a "foamed plastic combination upholstery".4

And the start of what was to be a long relationship between Verner Panton and Metzeler.

A relationship initially developed in cooperation with the Stuttgart based manufacturer Alfred Kill, themselves an interesting moment in the development of the European, for all the German, furniture industry, a company last mentioned in these dispatches in context of Hans Gugelot, and who we will return to in more detail before all too long. And with whom Verner Panton and Metzeler developed projects as varied as, and amongst others, the 1963 Flying Chairs, so-called because they are; the Multi-level Lounger, an early example of a team hub, and which offers not uninteresting potential as a socially distanced team workspace; and the Landscaped interior programme for Kaufhof, yes that Kaufhof, a lounge furniture programme featuring seven freely combinable elements, in addition to carpet and carpet wall tiles, and all available in a choice of ten colours. And thus an opportunity to create an individual, and immersive, space. And, arguably, one of the first examples of the modular sofa landscape concept that is today so ubiquitous.

At around the time of the development of the Landscaped programme attention in Memmingen clearly began to turn to furniture in wider contexts, and for all furniture which could be used in conjunction with Metzeler's mattresses: beds.

When, why, and initiated by whom, we no know; what we do know is that in 1966 no fewer than three patent application processes were started for bed designs by various combinations of Walter Baacke, Wolfgang Römer and Verner Panton.5

All three beginning from the same, above quoted, (perceived) problems with the, then, standard bed frames, and seeking solutions.

And a trio of projects from which that developed by Verner Panton alone, is for us the pick of the crop. And a genuinely very pleasing project, and, we'd argue, pretty radical.

Even for the mid-1960s.

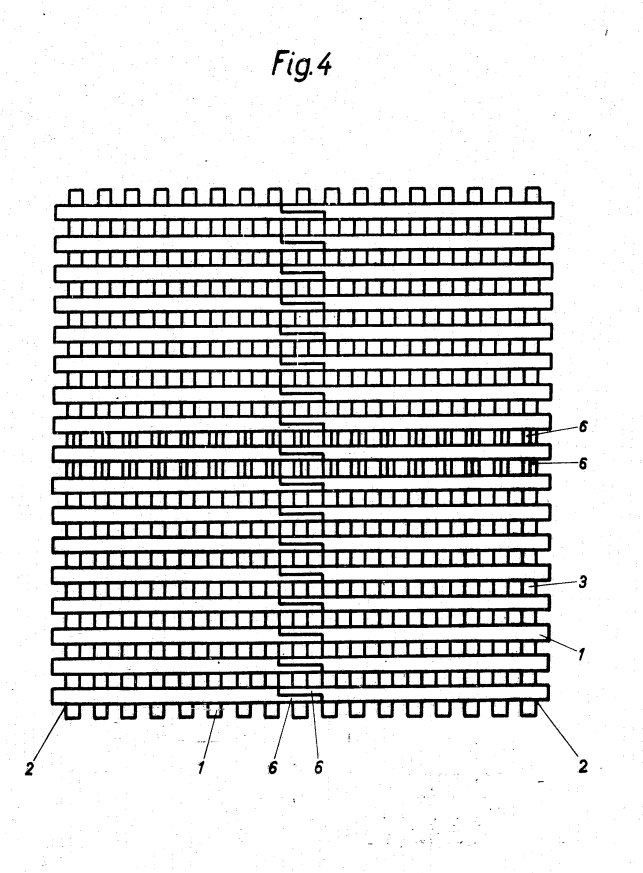

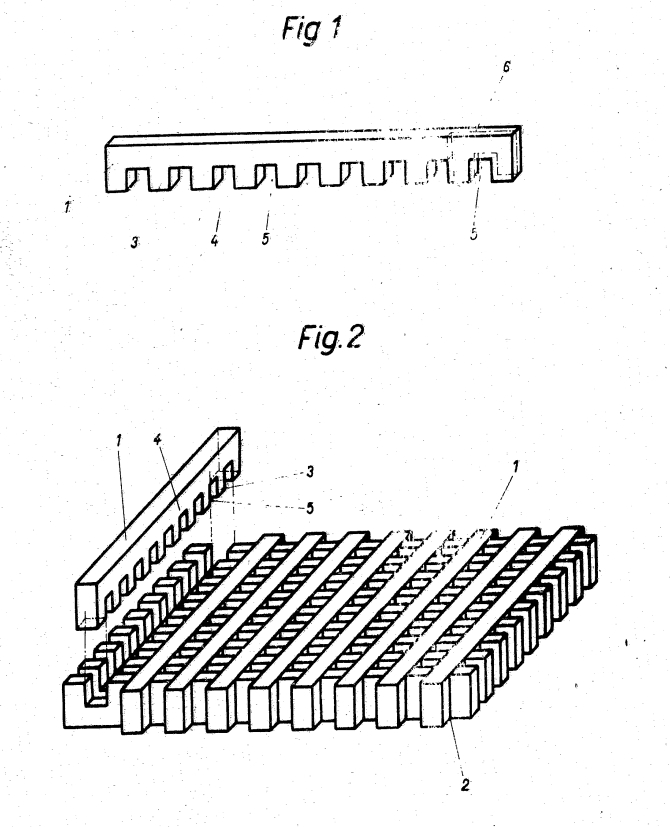

For all its, claimed, radicality, the Panton Bed is an astoundingly simple concept; but then, are all the most radical concepts not also the simplest? An astoundingly simple concept based around an equally astoundingly simple 1m long comb-esque element which can be interlinked into other 1m long comb-esque elements: 18 such interlinked elements, 9 longitudinal 9 latitudinal, creating a 1m x 1m pedestal. A 1m x 1m bed.

A 1m x 1m bed is however, as the patent application correctly notes, "not big enough for adults".6 Is at best suitable for a small child.

And thus Panton's comb-esque elements are/were designed to interlink not only vertically, but horizontally; the ends of the elements foreseeing a connection with the ends of other elements, and thus enabling the construction of a 1m x 2m pedestal, a single bed, or a 2m x 2m pedestal, a double bed.7

It's not Plug and Play, but Plug and Sleep!!!..... oh stop it!!!....honestly!!!

Or if you so will, it is a western interpretation of the Japanese futon; and, we'll argue, a very, very, early example of the raised pedestal western interpretation of the pedestal-less Japanese futon that is today as ubiquitous as modular sofa landscapes. Alternatively, it's a highly refined interpretation of the centuries old student practice of placing a mattress atop wooden pallets.

But whatever position you take, and indeed from whichever Verner Panton's concept arose, there is a deliciously satisfying elegance to the solution.

Yes, if with a couple of problems. For all the question of air flow, an important consideration in keeping any mattress healthy. However, on the one hand Verner Panton was more than aware of such a challenge and included small notches in the elements which enable the forming of channels through which air can flow underneath the mattress. On the other hand we'd argue the connecting of 9 longitudinal elements with 9 latitudinal is structurally, statically, unnecessary; 6 x 6 should be enough, perhaps 5 x 5, and if you then keep the nine gaps in the elements you gain even more air flow underneath the mattress

And on the all important third hand, we see the Panton Bed's primary use as a guest bed, and thus with a mattress that isn't permanently in place. A use as a guest bed aided, informed, by the reduction of the base down to 1m long elements, and thus short elements, which eases storage when not in use; and when employed with a thin futon mattress we can well imagine a product that fits in a small canvas bag, or a small box, possibly in a bedside table, certainly something that can be easily and unobtrusively stowed when not in use. And when in use can be used as a small child's bed, a single bed, two single beds, a double bed, or combinations thereof. As required.

And thus a solution with a deliciously satisfying elegance.

In addition the reduction to standardised 1m long elements eases, optimises, production. And apropos production, from which material should the elements be crafted?

According to Verner Panton, the elements "can be made of plastic, in particular polystyrene or other rigid foam, wood or metal".8

Whereby, "the particular advantage of rigid polystyrene foam is that it is extremely light, meaning that a bed pedestal can easily be put together by a single person and also lifted, turned or set aside without the need to first dismantle it"9

And although the recommendation for a synthetic material may sound "typically Panton", that would be to misunderstand the Panton oeuvre; and in many regards the genuinely "typically Panton" in the Panton Bed isn't to be found in the material, but in more contentual considerations.

Considerations which allow one to approach a better understanding of that (often misunderstood) Panton oeuvre.

Considerations such as the Panton Bed's variability. Its transience. That it can constructed, deconstructed and reconstructed as required. That it can be used or stowed.

Functionalities that go back to the very start of his career. Verner Panton's very first published design the 1953 Bachelor Chair through Fritz Hansen, a work that can, must?, be considered in context of Verner Panton the 1950s nomad, is and was a flat-pack object which the user assembles themselves, and when not required, or when you're in transit in your VW camper van, can be dismantled and stowed. Similarly space-saving variability can be found in objects such as, for example, the 1965 Partyset, a family of moulded plywood tables/stools which Matryoshka-esque stack inside one another; or the Barboy bar trolley from 1963 which when not in use stands in a space as an unobtrusive side table, a dumb barman more than a dumb waiter. And a work which in its further proposed development to office furniture is a not uninteresting proposal in context of (the increasingly common) home office scenario.

Or considerations on the Panton Bed's use of a limited number of, standardised, components. Again a recurring feature of Verner Panton's canon, and as understood in, for example, the late 1950s Plexiglass-Series through Plus-linje which used one form as both the seat for a chair and as an ottomann; the system 853/854 for Hans Kaufeld and its employment of a limited vocabulary of flat steel supports and quadratic upholstered and unupholstered elements to construct a range of seating and table elements; while in the early 1970s Panton experimented with standardised lighting elements that could be stacked on top on one another to create Columns of Light.

And considerations on variability and standardised components that help underscore that, and despite what the regularly occurring unconventional, organic, forms may imply, Verner Panton's approach to and understanding of design was fundamentally informed by pre- and post-War Functionalism, an influence that can also be understood in, for example, the formal reduction of his works, for all their unconventionality they are only very rarely decadently or unnecessarily so, or the use of new, contemporary, materials

And considerations on variability and standardised components that help bring one to Verner Panton's development of systems. And reflections on that fact that although today Verner Panton is most popularly understood in terms of individual objects, one in particular, the greater part of his career, the greater focus of his career, was concerned with the development of systems.

And systems thinking, modularity, that can be observed and understood in projects such as, amongst many others and in addition to those mentioned above, the Studioline collection with France & Søn, the Series 420 with Thonet, the wire Pantonova collection for Fritz Hansen, or the 1973 System 1-2-3 with Fritz Hansen, a collection that in many regards can be considered a further development of the 1962 upholstered seating collection for Storz & Palmer, and which as Panton described in a 1974 patent application was designed such that, "one and the same seat element can optionally be provided with different backrests, thus allowing for a large variety of different seating and reclining furniture to be produced from a small number of components."10

Much like the Panton Bed allows a variety of sleeping arrangements to be produced from a small number of components.

And systems thinking, modularity, that Verner Panton not only applied to furniture and lighting but to spaces: for example, the Visiona 2 installation from 1970, that polychromatic reflection and consideration on the domestic space and our relationships to our homes, was, essentially, a modular landscape. And while marginally more immersive than that offered to Kaufhof customers with the Landscape programme, was essentially the same.

And the Visiona 2 installation, as with the 1968 Visiona 0 installation, was, largely, realised in Metzeler foam.

Post-Visiona 2 Metzeler and Panton's cooperation continued and the early 1970s seeing the release of works such as the modular Weave sitting/lounging/reclining/lying system; the Two-level seat, so-called because it is; or the Cloverleaf Sofa, a work whose botanical associations allows for a moment of reflection on the role of the gardener Arne Jacobsen in the development of the organic formal understandings of a Verner Panton.

The last published Metzeler and Panton cooperation was the ever glorious Sitting Wheel from 1974, a concept that to this day one finds students reinventing as a "novel" understanding of seating. But there is no need to reinvent the (sitting) wheel. And a project, which, possibly, possibly not, arose as a combination of two important Metzeler business areas: seating upholstery and tyres.

That the Sitting Wheel marks the end of Verner Panton and Metzeler's cooperation is possibly, possibly not, related to Bayer's 1974 acquisition of Metzeler and the therefrom resulting corporate reorganisation and repositioning. However, in the preceding decade and a bit the cooperation with Metzeler, and for all with Metzeler's foam, allowed Verner Panton to develop, and for all demonstrate, his understandings of interiors, of furniture and of the relationships between interiors, furniture, individuals, for all that those relationships needn't be, shouldn't, be, aren't, static, and that our furniture shouldn't be considered something one adds to a space but a component of the space, and thus should/must contribute to the active use of that space. An interior as a fluid, interactive, landscape, not the still life the artist reduces it to. And while, and as previously noted, for all that much of Panton's canon may be understood as being from the realm of unrestrained kaleidoscopic fantasy, through his reflections and considerations Verner Panton predicted many of the more mundane, and ubiquitous, accoutrements of contemporary interiors.

Including, arguably, the raised pedestal western interpretation of the pedestal-less Japanese futon. If through a project that regrettably was never realised.

And which, we'd argue, is a state of affairs that needs to be rectified, not only because Skønseng is a product that is unquestionably as relevant today as it was in 1966, but as a project is an all too rarely consulted, yet highly informative, instructive and integral component of the Verner Panton biography and oeuvre.

A biography and oeuvre that we all really need get to know and understand better than we do.

And where better to start getting to know a designer you think you know, than with projects you don't.......

1Offenlegungsschrift 1 554 025, Bett fuer eine Matratze aus Schaumstoff od.dgl, Anmeldetag 28.07.1966

2Hanne Horsfeld, Innovation - Integration - Provokation. Verner Pantons Sitzmöbel, in Alexander von Vegesack & Mathias Remmele [Eds.] Verner Panton. Das Gesamtkunstwerk, Vitra Design Museum, 2000

3A nonsense word, but in Danish "Skøn Seng" could be understood as "graceful bed", which it is. And yes a Danish name implies a Danishness, but product names are marketing, and marketing is happiest with fuzzy truths. And Skønseng is also similar to the Norwegian village of Skonseng, whose relevance to the naming of a bed will be self-explanatory to all familiar with the endowing of product names in Swedish furniture warehouses.

4md Nr . 11 November 1965, page 558 (Available via https://www.verner-panton.com/de/person/press/11/index.html accessed 20.11.2020)

5see also Offenlegungsschrift 1 554 013, Bett fuer eine Matratze aus Schaumstoff od.dgl, Anmeldetag 04.03.1966 & Offenlegungsschrift 1 554 014, Bett fuer eine Matratze aus Schaumstoff od.dgl, Anmeldetag 04.03.1966

6Offenlegungsschrift 1 554 025, Bett fuer eine Matratze aus Schaumstoff od.dgl, Anmeldetag 28.07.1966

7Theoretically one could create platforms of any size, and thus allowing consideration for applications other than beds. In addition Panton also proposed an external skirt that could be wrapped around the outside and thereby framing the whole. We consider such unnecessary and so have ignored it. But it is in the patent application

8Offenlegungsschrift 1 554 025, Bett fuer eine Matratze aus Schaumstoff od.dgl, Anmeldetag 28.07.1966

9ibid. As a possible metal Panton suggested magnesium. Which isn't a metal popularly known in furniture design. And which arguably wasn't a metal in furniture design until 2019 when Magis launched Vela by Gilli Kuchik & Ran Amitai in Milan. Vela still isn't officially in Magis portfolio, but very much is a case of watch this space.....

10Offenlegungsschrift 24 21 970, Sitz- bzw. Liegemöbel, Anmeldetag 07.05.1974