Given the very close connections between Le Corbusier and France, one could be forgiven for, occasionally, forgetting that he was born in Switzerland.

With the exhibition Le Corbusier and Zürich the Museum für Gestaltung allow not only an insight into the Le Corbusier biography as charted by Switzerland's largest city, but also of his not always easy relationship with the country of his birth.

The most visible, tangible, relationship between Le Corbusier and Zürich is without question the building hosting Le Corbusier and Zürich. As noted from the Museum für Gestaltung's 2019 exhibition Mon Univers, the Pavillon Le Corbusier was commissioned in 1960 by Zürich gallerist Heidi Weber, construction beginning in May 1964, and stopping abruptly in August 1965 with Le Corbusier's sudden death while swimming off Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. The project ultimately being completed in 1967 under Heidi Weber's direction, and as Le Corbusier's last work; a work which thereby, logically, stands at the end of the story of Le Corbusier and Zürich, and that most fittingly as it is also in many regards a building that encapsulates much of the essence of the relationship between Le Corbusier and Zürich, between Le Corbusier and Switzerland ... but let's start the beginning......

Le Corbusier and Zürich the story, and Le Corbusier and Zürich the exhibition, both open in 1915 and thus at the very early stages of Le Corbusier's career, or perhaps more accurately put the later stages of Charles-Édouard Jeanneret's career, as he then (still) was, and with an interior architecture project realised for his cousin Marguerite Jeanneret and her new husband Adolf Hauser in the city's Gemeindestrasse; his first project outwith his native La Chaux-de-Fonds and the Jura mountains; a project which saw him combine two apartments into one home; a project which, not uninterestingly, includes a partition wall between the nursery and boudoir which sounds not unlike George Nelson's 1944 Storagewall; a project which, as the cheekily placed Modulor Man in the bed of the guest bedroom in the 1999 recreation of the floorplans underscores, was as much Charles-Édouard Jeanneret's pied-à-terre in Zürich, as his cousin's home. And a project represented in Le Corbusier and Zürich by, in addition to sketches, plans, photographs and Charles-Édouard's invoice to his cousin for CHF 524.75, two pieces of furniture designed for the boudoir by Charles-Édouard Jeanneret: a dressing table and a chair, both in wood, both painted yellow, both unassuming and elegantly reserved, both very much expressing a neoclassical inclination, and with the chair featuring a most generously scaled seat. Though not overly so, it is a very nicely balanced, and very satisfying work. And for all a nice reminder of Le Corbusier's origins, a reminder that he is more then béton brut and tubular steel.

At the time of the Gemeindestrasse commission Charles-Édouard Jeanneret was primarily employed as a lecturer at the École d’Art in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and where in 1916 he completed with the Villa Schwob his last work as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, before in 1917 moving to Paris, where in 1920 he became Le Corbusier; and under which name in November 1926 he gave two lectures in Zürich; one on Urbinisation to the Zurich Association of Engineers and Architects, and one on Architecture, mobilier, oeuvres d'Art to the Swiss Werkbund.

In 1930 Le Corbusier became a naturalised French citizen and in the following half decade undertook those projects which lie at the heart of both Le Corbusier and Zürich the story and Le Corbusier and Zürich the exhibition: not least because none of them were realised. A trio of unrealised projects which form part of a catalogue of unrealised Swiss projects, a catalogue of unrealised Swiss projects that it is much larger than his catalogue of realised Swiss projects, a catalogue arguably dominated by the Palais des Nations in Geneva, and a catalogue which unquestionably contributed to Le Corbusier's original rejection of Heidi Weber's proposed Zürich project, “Please understand" he informed her, "I’m not prepared to do anything more for the Swiss; they have never been particularly nice to me.”1

And a series of unrealised projects which as Le Corbusier and Zürich neatly elucidates, underscore the fact that, and to paraphrase Julian Barnes' narrator in Flaubert's Parrot,2 the works architects didn't build, the "houses they dreamed and sketched", are often as interesting as those they did, not least because they often serve as links in the development process of the architect, often offer valuable insights into the highways and byways via which an architect became that what they are known as and for, and always allow for new perspectives.

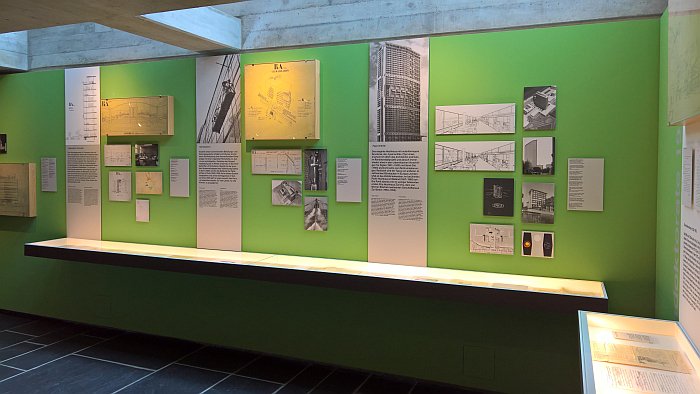

The unbuilt apartment block on the corner of Hornbachstrasse and Dufourstrasse, and thus but a short crow's flight from the future site of the Pavillon Le Corbusier, for example, containing elements such as the internal "streets" and the two level apartments which twenty years later would be employed in Le Corbusier's numerous Unité d'Habitation projects, similarly the collective spaces and shared services which are so central to first Unité d'Habitation in Marseille featuring equally centrally in his unrealised plans for workers housing on Hardturmstrasse, while his 1933 competition entry for the new headquarters of the Zürich based life assurance institution, Schweizerische Lebensversicherungs- und Rentenanstalt, offers not only delightful insights into Le Corbusier's approaches and understandings, but also a delicious "what if?" moment.

Intended for a site on Zürich's Mythenquai, one of the, at that time, last unbuilt sites on the left bank of the Zürichsee, Le Corbusier's proposal for the Rentenanstalt envisaged a ten storey office block whose internal organisation was based on a rationalised model of the workflows within the institution, a rationalised model depicted by Le Corbusier as an organism, a sketch displayed in Le Corbusier and Zürich showing a brain on the top floors where the management offices were to sited with nerves running down from that brain through the various departments. And an Organisation rationelle that not only awakens memories of that developed and employed three decades earlier by Frank Lloyd Wright in his Larkin Administration Building, but which allows one to understand that just as Le Corbusier famously understood a house as a machine for living in, so for Le Corbusier the office block was a machine for working in. And that in both home and office everything could be, and should be, structured, optimised and rationalised.

Understandings of Le Corbusier of a differing nature can be elucidated in the proposed use in the Rentenanstalt tower of his mur neutralisant climate control system. First experimented with in a limited form in the Villa Schwob, that last Charles-Édouard Jeanneret project, mur neutralisant envisaged the use of an exterior cavity wall, the interior of which was heated in winter and cooled in summer and thereby controlling the internal temperature of the building, and thus a component of Le Corbusier's vision of creating hermetically sealed, air conditioned, buildings, a photo in Le Corbusier and Zürich of a submarine very neatly, and not unamusingly, summarising the closed, self-contained, self-reliant system Le Corbusier was aiming to realise. Persistently, one could argue stubbornly, or valiantly, certainly unsuccessfully, aiming to realise: mur neutralisant being proposed for the ill-fated Palais des Nations; included in his 1928 Centrosoyus in Moscow, but for which it ultimately wasn't employed owing to considerable, verifiable, doubts as to the energy inefficiency/costs associated with the system; and which for similar reasons saw it rejected in the construction of his 1929 Salvation Army Cité de Refuge in Paris. Le Corbusier wanted mur neutralisant in a large scale project. No-one would let him realise it. The Zürich Rentenanstalt proposal with its glass curtain cavity wall exterior being in many regards a last throw of the mur neutralisant dice. And the first throw of a diamond-esque type lentille profile; a profile that although Le Corbusier, again, often proposed, he, again, never realised. And which means that had his Rentenanstalt proposal been selected it would have endowed Zürich an interesting, and not unimportant, contribution to Le Corbusier's physical canon and thus allowed for improved, deeper, understandings of that canon.

But it wasn't.

Officially because it didn't conform to numerous components of the brief, including being too tall and having no inner courtyard; unofficially, and as with the Palais des Nations, because it was simply too modern for prevailing Swiss sensibilities. In contrast, one notes, to the much more accommodating French sensibilities of the 1920s and 30s.

And thus with the demise of the Rentenanstalt project ends Le Corbusier's attempts to build in Zürich.

Until 1960.

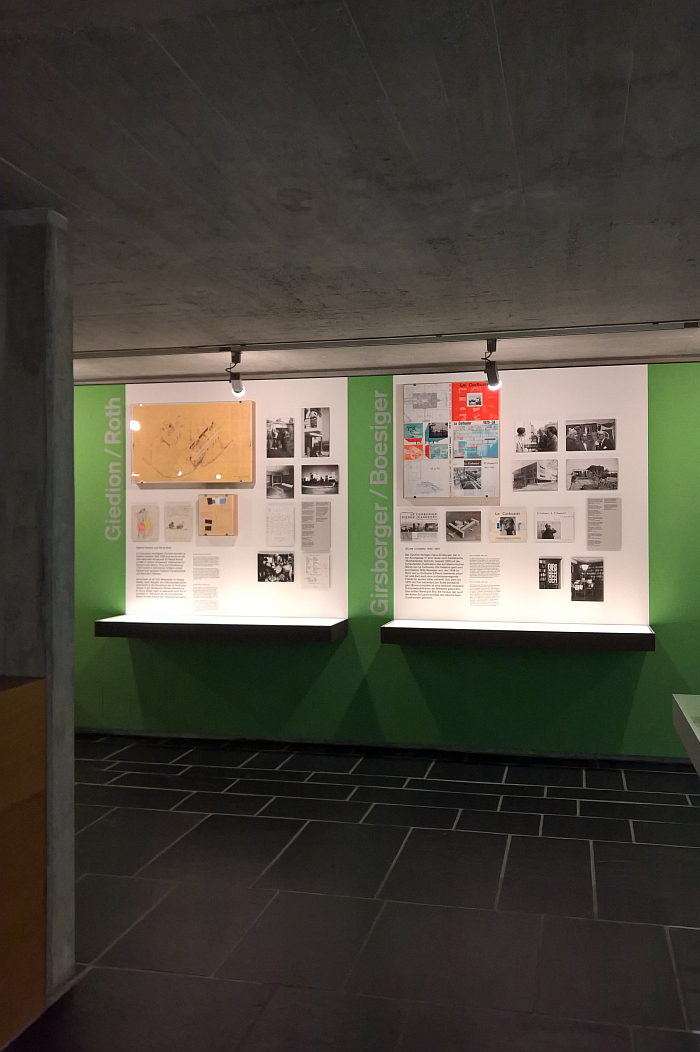

Beyond the architectural projects Le Corbusier did and didn't realise, Le Corbusier and Zürich also briefly discusses those Zürich based individuals and institutions who aided and abetted his career, those Swiss who were nice to him.

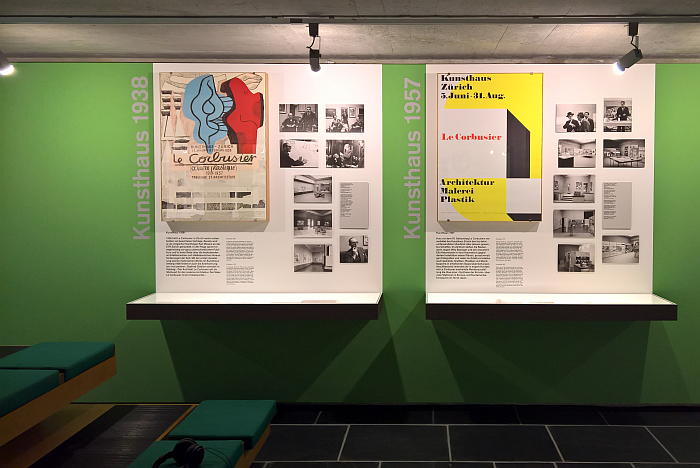

Institutions such as the Zürich Kunsthalle, who in 1938 and 1957 staged exhibitions of Le Corbusier's art and which in doing so helped underscore that Le Corbusier was more than an architect. And individuals such as the architecture critic and author Sigfried Giedion who as well as being a co-initiator alongside Le Corbusier of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, was an active advocate and supporter of and for Le Corbusier who rarely missed an opportunity to recommend him; individuals such as the publisher Hans Girsberger who from 1929 onwards, under the editorship of Willy Boesiger and in close cooperation with Le Corbusier, began publishing details of all of Le Corbusier's architectural projects, a work that with its final volume in 1970 became the 8 volume Œuvre complète, one of the most important, if at times overly celebratory, Le Corbusier reference sources; and individuals such as the gallerist Heidi Weber.

A native of Münchenstein near Basel, in 1957 Heidi Weber opened an interior design gallery, Studio Mezzanin, in Zürich's Neumarkt, a business whose orientation, in terms of furniture, can perhaps be best understood by its original focus on the Hermann Miller collection: the opening exhibition featuring furniture designs by Charles Eames3 and George Nelson, while a contemporary photo of Studio Mezzanin also clearly depicts works by Isamu Noguchi. Studio Mezzanin's furniture portfolio was very contemporary.4 And would soon become moderne.

Having first met Le Corbusier in August 1958 in context of his art, in September 1958 Weber visited Le Corbusier in his Paris atelier, and where she was introduced to Le Corbusier's furniture designs,5 liked what she saw, and in December 1959 acquired from Le Corbusier the exclusive license to produce and sell four of his designs in Europe and America: specifically the LC 103 armchair and LC 104 chaise longue, both of which had been briefly manufactured and distributed by Thonet in the late 20s/early 30s, and the LC 101 and LC 102 lounge chairs, the former somewhat wider and squatter than the latter, and both produced and distributed for the first time through Heidi Weber in and from Zürich. Albeit a 1959 licence, and period of the Le Corbusier furniture (hi)story, which doesn't exist in the official Le Corbusier biography. So keep schtoom, and if anyone asks, you didn't read it here 🤫 😉

And a 1959 licence6 which, in many regards, initiated the contemporary popular fascination with Le Corbusier's furniture, but which for all enabled Heidi Weber to propose the Zürich construction project in 1960.

An idea which, after the aforementioned reluctance, Le Corbusier eventually came round to.

If an idea it then took the authorities in Zürich a little longer to come round to; the resistance that Le Corbusier had met in the early 1930s still existing three decades later, and as Heidi Weber later recalled, Le Corbusier, sitting in Paris, reading negative reports about the project in the Zürich press, had serious doubts that it would ever be realised.7 A certain sense of Déjà-vu must have fallen over his atelier/apartment in the rue Nungesser et Coli

But, eventually, permission was granted. Le Corbusier could finally realise a building in Zürich, in Germanophone Switzerland. Had he not, there would be no exhibition on Le Corbusier and Zürich.

Opened in July 1967, the, then, Heidi Weber Museum – Centre Le Corbusier was conceived less as a Le Corbusier museum per se and more a space for exhibitions, workshops and events on themes related to Le Corbusier and his work, but presented and discussed in wider contexts. And a space which quickly ran into financial difficulties, financial difficulties and intermittent periods of closure which in many regards form the central narrative of the institute's neigh on fifty year (hi)story; and which, and reading between the lines as best and as subjectively as we can, was a situation the authorities in Zürich/Switzerland did little to mitigate. And thus a (hi)story which, we'd argue, not only wouldn't have surprised Le Corbusier, he wouldn't have expected the Swiss to assist and help with one of his projects; but which also poses interesting and important questions about the handling of and dealing with architectural legacies, about the decisions that are made as to which legacies, which components of which legacies, are worth publicly supporting and maintaining and which can/should be left to private initiatives and foundations. And who should be charged with making such decisions...... Politicians? Architects? Academics? Everyone?

And a debate not approached in Le Corbusier and Zürich, although arguably it should be, must be; the story of Le Corbusier and Zürich doesn't end with his death, nor should the exhibition Le Corbusier and Zürich, the (hi)story of the Heidi Weber Museum – Centre Le Corbusier being as it is an unavoidable component of any study of the relationship between Le Corbusier and Zürich, of the relationship between Le Corbusier and his native Switzerland. Not least because it is one of only very, very few buildings Le Corbusier realised in Switzerland, and the only one - after three unsuccessful, and at times hostilely received, attempts - Le Corbusier realised in Zürich.

In 2014 Heidi Weber's 50 year leasehold on the ground on which the building stands expired, and ground and building reverted to the city authorities, which is a story in it's own right; and having taken possession of the building, the city also took greater interest in the building, and in 2019, and following extensive renovations and restorations, it was re-opened as the Pavillon Le Corbusier under the management and curation of the Museum für Gestaltung.

A decision which, and whatever ones views on the building's longer history, can only be welcomed. It is a joyous space.

Presenting a mix of photos, documents, publications, sketches, models and furniture, Le Corbusier and Zürich allows for an entertaining, comprehensible and easily accessible trilingual German/French/English introduction to a very specific aspect of the Le Corbusier biography. An introduction which not only allows for reflections and considerations on Le Corbusier's relationship with his native Switzerland, and also on the divergent, contradictory?, relationships of the more traditional disposed Charles-Édouard Jeanneret with Switzerland and that of the more contemporary focussed Le Corbusier; but an aspect which arguably because it is so specific, allows for a sharpened focus on aspects of the wider Le Corbusier biography, a sharpened focus on Le Corbusier's understandings of and approaches to both his work and architecture, and also a sharpened focus on the networks and connections which were of unquestionable importance in the development of his career. As networks and connections are in the development of any career.

In addition, and as with Mons Univers, Le Corbusier and Zürich allows for an understanding of Le Corbusier beyond the popular, and very unsatisfying, image of a serious, stern, saturnine looking man in round glasses: whereas Mon Univers allowed one to marvel at images of Le Corbusier sat working at a table populated by dirty dinner plates while stroking a cat, or with a vase on his head like the proud winner of a sports contest; Le Corbusier and Zürich features Le Corbusier holding a piglet and Le Corbusier (and Pierre Jeanneret) dressed up as, and obviously thoroughly enjoying the fact they are dressed up as, tunic-coated drummer boys. And which in doing so compliments and extenuates the discussions on the various projects, and also reflections on the space in which those discussions are being staged, in allowing one to approach a much more differentiated and thereby more probable, realistic, impression of Le Corbusier the man and Le Corbusier the architect.

Le Corbusier and Zürich runs at Pavillon Le Corbusier, Höschgasse 8, 8008 Zürich until Sunday November 29th.

Full details can be found at https://pavillon-le-corbusier.ch/

1"Wissen Sie, für die Schweizer tu ich überhaupt nichts mehr; sie waren noch nie nett mir gegenüber..." http://www.centrelecorbusierbyheidiweber.com/daten_und_fakten.html accessed 25.06.2020

2We also paraphrased Flaubert's Parrot in our post from Mon Univers. We have read other novels, honest; but clearly we must make some subconscious connection between the biography of Le Corbusier and the biography of Gustav Flaubert. Why? We no know, but we will investigate....

3As previously noted until the mid-1950s "Charles and Ray Eames" were officially and publicly "Charles Eames", Ray only being publicly acknowledged with the launch of the Lounge Chair in 1956.

4see Heidi Weber. 50 Years Ambassador for Le Corbusier 1958-2008, Heidi Weber Museum - Center Le Corbusier Zurich, 2009 pages 168/169. In addition on page 19 is a picture of Heidi Weber and Charles Eames in Zürich in 1957 Accessible via https://www.lecorbusier-heidiweber.ch/en/media-libary/publications (accessed 25.06.2020)

5Heidi Weber is adamant, vehement, often for our taste a little too vehement, in her position that the four works she produced, the contemporary LC1, LC2, LC3, L4 are Le Corbusier alone, underscoring that the contemporary LC7 and LC8 were specifically excluded from the contract at Le Corbusier's behest because he announced they were Charlotte Perriand alone. Today all are officially by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand. Here isn't the time nor place for an extended discussion on the genesis of the LC collection, we'll save that for another day. In the interests of simplicity, readability, in the text we list the four are Le Corbusier alone. Something we'd question.....

6In the interests of completion, in 1964 and 1965 Heidi Weber sub-contracted her licence to Cassina, who have exclusively produced the works ever since; initially on the basis of Heidi Weber's licence before taking over the exclusive license following the expiry of Weber's licence in 1978.

7Ich musste gegen die ganze Welt kämpfen = J'ai dû me battre!, Heimatschutz Patrimoine, Vol. 109, Nr 1 2014, page 6-9

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious….