"In many workshops and offices it is regularly attempted to achieve both direct and semi-indirect lighting by means of large, single, light sources, that is, to work only with ample general lighting. Yet as pleasant as this type of lighting may be, in many cases it proves unsatisfactory on account of certain inherent shortcomings"1

So opined in 1926 the German engineer Curt Fischer.

Rhetorically. For in 1919 he had already patented his first solution to resolving such "inherent shortcomings".

How, and where his considerations have taken contemporary lighting design, are discussed and explored in the exhibition 100 Years of Positionable Light at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

It is, we'd argue, a truism in design that many, all?, of the best designs are invariably those that you don't realise were designed: objects, for all functionalities, that one just assumes came into being with the Big Bang and have always been part of out wider universe; objects so intuitive and logical that one gives them no further thought; objects as if of Natural Law; objects so stupidly, stupidly simple one can't imagine someone had to, could, invent it.

Objects such as the positionable work lamp, the positionable desk lamp. A ubiquitous, logical, stupidly, stupidly simple object that despite what all rationale tells you, hasn't always existed.

And an object whose (hi)story, whose genesis and development, allows not only for reflections on the relationship(s) between lighting and wider social, technical, economic, et al realities, but also on the relationship(s) of the designer to the objects they develop.

Or put another way.....

In many regards the story of positionable light begins in the late 19th century with the start of mass electrification, and for all the development of the electric, incandescent, light bulb, one of those moments and objects that genuinely revolutionised society. And which in doing so demanded new solutions in order to properly exploit its benefits. And whereas in the early decades of the 20th century the likes of a Poul Henningsen busied themselves with studying the diffusion of electric light in order to develop static, glare-free, lighting for the home, the likes of a Curt Fischer busied themselves less with the diffusion of light as the diffusion of shade, and for all the inevitable shadows that arise on a workbench illuminated solely by static wall or ceiling mounted lighting.

Specifically the shadows which arose on the workshop benches of Curt Fischer's company Industriewerk Auma Ronneberger & Fischer in Auma, Thüringen, a company that Fischer, until then a radio engineer and aspiring airship pilot, took over following the death of his friend Konrad Ronneberger in the Great War, a company which at that point was predominately a supplier of machines and tools for the Thüringen porcelain industry, and a company whose workshop benches were obviously so inefficiently, impractically, infuriatingly, illuminated that Curt Fischer felt compelled to act.

Quite aside from enabling lighting where it was needed, and the repulsion of shadow from where it wasn't, a central focus of Curt Fisher's considerations was the development of a solution that could be operated with one hand and without tools, that a worker should be able to reposition the light as needed, and without interrupting their work flow. If, like us, you are currently sat at a desk with a positionable lamp, we'll wager that while reading that last sentence you almost certainly reached out and repositioned your lamp. With one hand. We did.

Curt Fischer's initial solution was a wall mounted lamp which could be moved horizontally via a concertina mechanism to which was attached an adjustable lamp head atop a short arm, a design that enables the light to be pushed, pulled, raised, lowered, twisted, positioned, as, when and where, required, and with just one hand. And an object which opens 100 Years of Positionable Light as a Midgard Nr. 110 from ca. 1925

And an object which helps explain further aspects of the (hi)story of positionable light: firstly that a patent isn't the same as a commercially available object, getting from former to the latter takes a little time, especially against the material shortages and economic realities of the Weimar Republic; secondly that having developed his lamp Fischer also formed a new company, Midgard, to produce and distribute his lighting designs; and thirdly that Curt Fischer wasn't alone in his thoughts on positionable lighting. Or more accurately put, the third point is highlighted by the so-called Lampe Gras patented in 1921 by the French engineer Bernard-Albin Gras, which stands next to the Midgard Nr. 110, a lamp whose articulation relies on different approach to a similar problem, and two physically contrasting yet conceptually similar ca 1920 lamp designs which lead you into, and inform, the further discussion on and exploration of the development and (hi)story of positionable light.

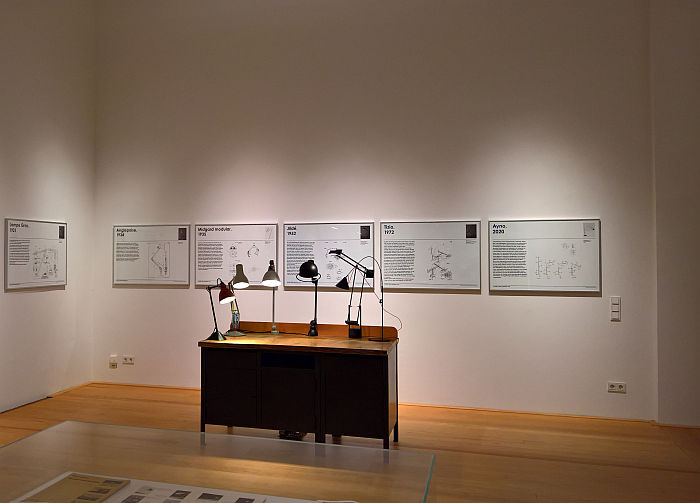

Based around seven short chapters the narrative of 100 Years of Positionable Light unfolds, or perhaps put, concertinas, away from Curt Fischer's 1919 patent to discuss and explore its subject both in the direct context of Midgard, for example through objects such as the Nr. 113 from 1924 and which sees the wall mounted concertina mechanism replaced with a desk mounted clamp and the adjustable lamp head attached to a long, positionable, bent tubular steel support, and an object which was key in the growth and establishment of the company; and also through discussions on parallel subjects including spring balanced lighting as perhaps most popularly exemplified by George Carwardine's Anglepoise, on Christian Dell, a not unimportant figure in the development of positionable lighting in the inter-War years, and also on Bauhaus: both Bauhaus's (hi)story with positionable lighting and Bauhaus's (hi)story with and to Midgard.

The latter illustrated and discussed through, for example, photos of Midgard lamps in projects by Bauhäusler, including the ADGB Bundesschule in Bernau, one of the few external architecture projects realised at Bauhaus, or a letter from Walter Gropius to Curt Fischer in which Gropius organises promotional photos of Midgard lamps, and a discussion which for all helps contribute to the deconstruction of the primacy of Bauhaus in popular understandings of all things inter-War design, helps further underscore that Bauhaus wasn't alone in inter-War Germany, far less inter-war Thüringen. The former taking, in many regards, as a central focus projects developed at Bauhaus for Körting & Mathiesen, aka Kandem, Leipzig, and more importantly projects not developed at Bauhaus for Kandem Leipzig, but which everyone thought were: specifically the Kandem 934 tubular table lamp and 830 swivel lamp, works which popular convention until now had assigned to the Bauhäusler Heinrich Siegfried Bormann, who was at that time responsible for the collaboration between Bauhaus and Kandem, but which research by 100 Years of Positionable Light curator and initiator Thomas Edelmann has now assigned to the goldsmith Werner Glasenapp. Who was never at Bauhaus. Who was at the Staatlich Akademie für Kunstgewerbe Dresden.

And a situation which underscores one of the problems in researching in areas such as inter-War design: detailed, primary, information is often very, very, limited, one relies to a great extent on secondary sources; consequently, that which is once incorrectly noted tends to be, inadvertently, incorrectly noted ad nauseam, ad infinitum. And for us it is always particularly satisfying when a truth is righted. When credit is given where it is due, not where convention has placed it. A situation which also refers to the exhibition 100 Years of Positionable Light and its reuniting of Carl Fischer and Midgard with their key roles in the earliest developments of positionable light, roles more recent history has denied him and them.

Having taken the visitor through a tour of historic, and occasionally very rusty, lighting designs, 100 Years of Positionable Light ends with a look at positionable light in more contemporary contexts, including with LED, a light source every bit as revolutionary and demanding of new forms as the incandescent light bulb once was, and as exemplified by works such as the Roxxane Office by Rupert Kopp for and with Nimbus or Lucy by Henk Kosche for and with Erco; and is extenuated by a presentation of patents which mark selected milestones in the development of positionable lighting, starting from Curt Fischer's 1919 patent and moving over the likes of the aforementioned Anglepoise, Jideé by Jean-Louis Domecq, Richard Sapper's 1972 Tizio for Artemide and ending with Stefan Diez's AYNO for Midgard, a lamp formally launched at IMM Cologne 2020.

And which brings us to the Thonet Test.

Developed by ourselves in context of the exhibition Sitting – Lying – Swinging. Furniture from Thonet at the Grassimuseum Leipzig, the Thonet Test is a very poorly defined test which in essence poses the question if an exhibition devoted to a particular manufacturer, and/or sponsored by a manufacturer featured in the exhibition, is just advertising for that manufacturer? And which we almost only ever need apply in context of Thonet, Thonet being, apparently, the only furniture or lighting manufacturer ever afforded monographic exhibitions. And which in Hamburg we need apply not only in terms of Midgard, but of............ Thonet, who are not only a production partner of Midgard but who, alongside Midgard, are co-sponsors of the exhibition.

And a test 100 Years of Positionable Light passes............ which you knew, because if it hadn't you wouldn't be reading this.

On the one hand the narrative of 100 Years of Positionable Light is very much one of developments in lighting design over the past 100 years, with a very specific focus on a very particular functionality of lighting, and, and much as we noted from Munich in context of Die Neue Sammlung's exhibition Thonet & Design that "Thonet are so central to the development of furniture design and the furniture industry, its impossible to discuss such without mentioning Thonet", so you can't really discuss positionable lighting without discussing Midgard. For all given that the discussion on Midgard in context of positionable lighting is relatively new, Curt Fischer being, as noted above, in many regards a re-discovery of recent years.

And on the other hand, not only is 100 Years of Positionable Light not only Midgard, it makes no attempt to give a pre-eminence to Midgard, or to argue that all developments since 1919 can be traced back to Midgard. Curt Fischer is very much positioned as the pioneer, but all that which flows from his 1919 patent, and Bernard-Albin Gras's 1921 patent, is handled independently of Fischer/Midgard, if as part of a continuum. Is very much an argument for for positionable lighting, but not for the products of one manufacturer.

And so while, yes, we would, as always, very much prefer it if the manufacturers featured weren't involved in the organisation and design of an exhibition, we do understand that exhibitions cost money to arrange and stage, and if the shipping companies, merchants and banks of Hamburg don't feel themselves obliged to help advance cultural understandings in a city that has advanced their wealth, then someone has to. And we'd argue that which is presented in 100 Years of Positionable Light should, must, be presented. If including AYNO is a touch cheeky, as in friendly, nice, cheeky, like taking two biscuits when offered one.

Aside from the variety of lighting solutions on show, a, the, real joy of 100 Years of Positionable Light is the chance to get up close and personal with the lights. Presented as they are on their improvised Thonet shelving without the hindrance of glass panels, rear walls or pedestals, one can view them undisturbed from all perspectives, or at least can save those few placed higher up. And can thus properly explore, consider and regale in the similarities and differences, the nuances of the works and the developments of the century past, bob about across the room comparing works of different manufactures, eras, contexts, from the patents to the objects and back to the patents.

Which yes is nerdy, but so is the subject. And so is design. Designers are nerds, individuals who get caught up in the complexities of trivialities. Only very few designers ever develop anything fully new, much of design, certainly product design, is tinkering with the existing, be that with existing archetypes, with forms and objects that have passed unnoticed through centuries and civilisations and in doing so integrated themselves into the fabric of society, or tinkering with the work, the often very novel, revolutionary, works, of engineers such as a Curt Fischer or a Bernard-Albin Gras. Is an ongoing process of trying to improve that which exists, of evolving objects in context of evolving social, cultural, technical, economic, et al realities, of employing new processes for existing purposes, of employing new materials, such as the incandescent light bulb. And a process which requires a certain affinity with nerddom.

100 Years of Positionable Light allows you to live your nerddom to the full. Something we'd very much encourage, not only because losing yourself in the details allows you to better understand how lighting design has evolved and developed over the past century, nor how designers and engineers have contributed to those developments, but also because it helps move ideas of functional design away from images and into fine detail, away from the clamour of popular social media platforms and into the peace of the Kingdom of Nerddom.

Amongst those aspects that particularly caught our attention was the 6740 clamp lamp by Christian Dell for Gebr. Kaiser from the 1930s and which not only places the parabolic, shell-esque reflector of which Dell was so fond in a much more industrial context than one is used to, but confirms that contemporary swan neck lamps are but part of design's long helix; by the regular occurrence of ball bearing movements in many of the very early lamps, reminding us as it did of the Standing Task Light by Erik Wester, one of those projects we once obsessed about, and which we understand now, as we didn't then, of being in the tradition of inter-War lighting design, the intuitive movement that so caught us with the Standing Task Light being related to the origins of positionable lighting; and also the realisation that the concertinaing wall mounted lamp never really took off. And that, arguably, because despite the many advantages of the concept, despite being a logical, intuitive and stupidly, stupidly simple concept, it lacks a certain practicality in many contexts, that as pleasant as this type of lighting may be, in many cases it proves unsatisfactory on account of certain inherent shortcomings. Shortcomings the move from the concertinaing wall mount of the Nr. 110 to the bent tubular steel arm of the Nr. 113 overcame: and in doing so automatically posing new questions of possible further developments, of possible further evolutions. Questions which have been continually analysed and tackled by designers ever since. Every new solution adding to the debate and design's helix.

In addition to aiding and abetting the study of the lamps, the open and approachable nature of the display concept aids and abets the open and approachable exhibition layout, a layout which makes intelligent use of the space to house the exhibition with a natural, unhurried ease. One understands one has time to view the exhibition, and wants to take that time.

Time to view not only the 40+ lamps on show but also the various film clips and to engage with the numerous historical documents, photos, books etc, which help set the various objects in wider contexts, including a 1926 text by Curt Fischer in which he is at great pains to underscore the greater energy efficiency of individual workbench lamps, to underscore that employing individual lamps allows for lower electricity bills: yes, a sales pitch to those riding the economic roller coaster of 1920s Germany, but also a nice reminder that design, or more accurately industrial design, isn't just about functional or aesthetic aspects, but also economic.

In our post from Ingo Maurer intim. Design or what? at Die Neue Sammlung Munich we listed numerous facets of light, but didn't include light as being positionable. Because light isn't. Lighting design makes it positionable, is one of those ways lighting designers make the intangibility of light's energy a tangible good, make light useful and practical, and as 100 Years of Positionable Light very elegantly, coherently, and satisfyingly nerdily, underscores, while positionable light may not have arrived with the primordial glow of the Big Bang, it is a functionality of light that was sought as soon as technology made it possible, and a functionality of light which designers have continued to evolve and develop over the decades, and will continue to do so, for who can imagine a world without a lamp you can freely position with one hand. That would be most unsatisfactory. Almost unnatural.

100 Years of Positionable Light runs at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Steintorplatz 20099, Hamburg until Monday June 1st.

1Curt Fischer, Fragen der Innenbeleuchtung, Sonderdruck aus der Zeitschrift "das Eisenbahnwerk", Heft 4 05.02 1926 and as presented in 100 Years of Positionable Light at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Full details can be found at www.mkg-hamburg.de/100-years-of-positionable-light