Sitting unassumingly, and largely unnoticed, in the middle of Germany, the city of Gotha may have only little resonance with the majority, with the great unwashed; however, every European royal family can trace their lineage back to Gotha: most famously the English royal family through Queen Victoria's 1840 marriage to Prince Albert, but the royal houses of Sweden, Denmark, Spain, Holland, Norway, you get the idea, can all trace their lineage back to and through Gotha.

Gotha and royalty ✔

Gotha and inter-war Modernism ¿✔?

The (hi)story of Gotha and contemporary European royalty begins in the 17th century and the investiture of Ernest the Pious as Duke of, initially, Sachsen-Gotha and subsequently Sachsen-Gotha-Altenburg.

The (hi)story of Gotha and inter-War Modernism begins, more or less, in the 20th century and the investiture of Walter the Gropius as Director of the Staatliche Bauhaus in nearby Weimar, an institution which, as Inspired by Bauhaus explores, allowed Gotha to experience Modernism not only via a range of expressions, but also across the varied recent history of the city and region. A variety and range which allows the KunstForum to present an exhibition composed of three showcases, each given their own floor and starting, at least if like us you begin on the top floor, post-Bauhaus, post-War, in East Germany.

Amongst the many positions represented by early 20th century reformist, avant-garde, institutions such as Bauhaus was standardisation of construction, attempts, if you so will, to develop industrial building practices and systems: something which, and as discussed in context of, for example, the exhibitions Carl Fieger. From Bauhaus to Bauakademie at Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau or Shaping everyday life! Bauhaus modernism in the GDR at the Dokumentationszentrum Alltagskultur der DDR Eisenhüttenstadt, flowed, if albeit initially a little slowly backwards, from the Bauhauses into the DDR in the form of the Plattenbau, the sectional, prefabricated, tower block.

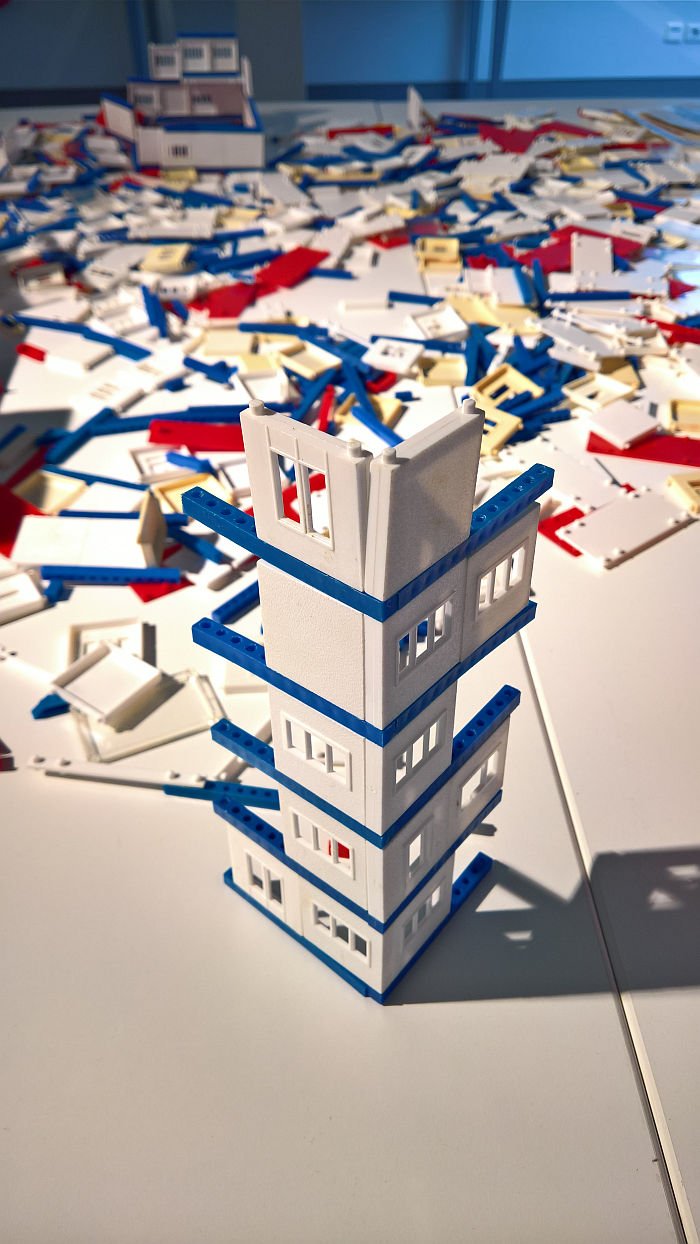

And as the toy Plattenbau, specifically the so-called Großblock construction system.

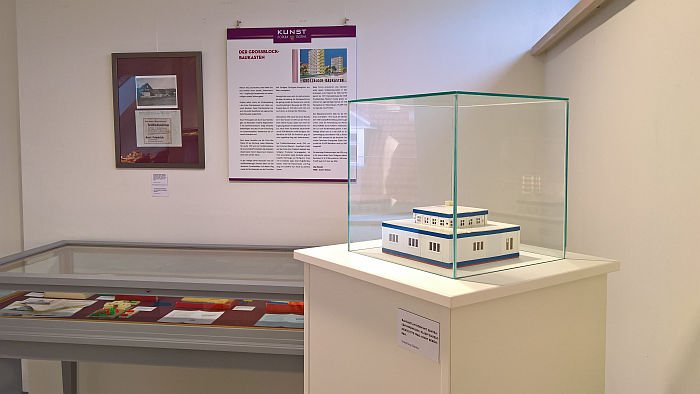

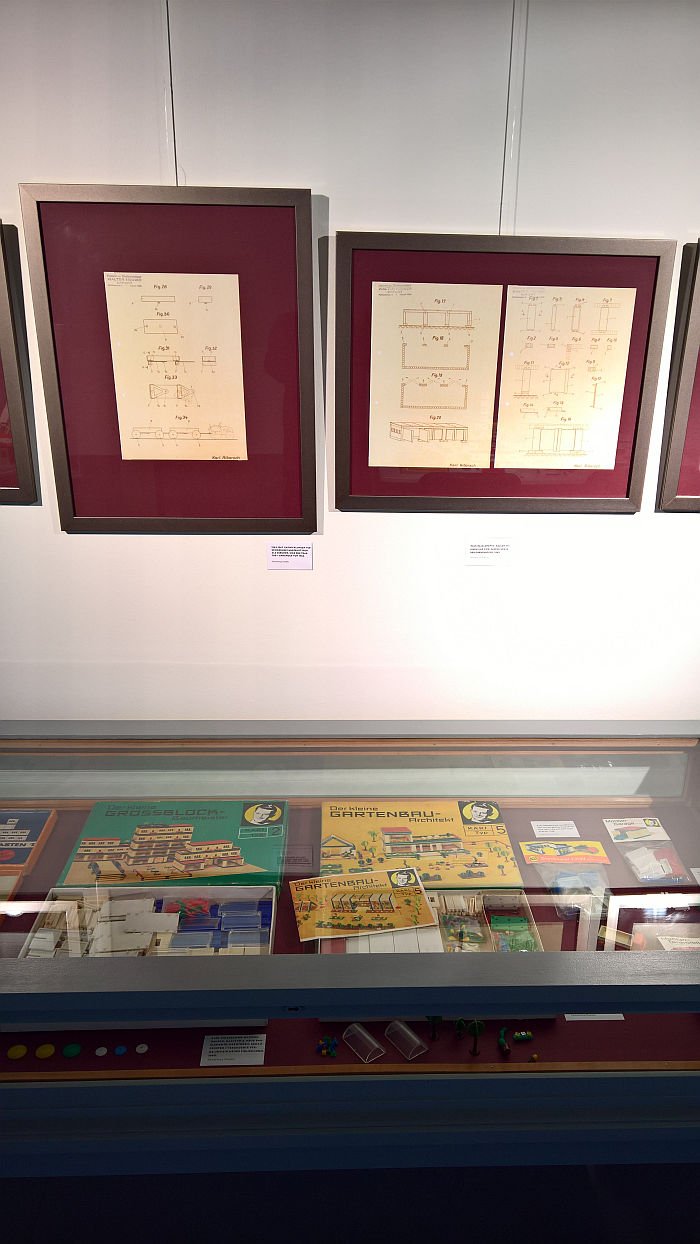

Originally developed in the early 1950s by Nürnberg based Rex-Plastic, the Großblock [Large Block] construction kit crossed, legally, as far as we can ascertain, from West to East, wandered, if one will, as free as a deer through the Franken and Thüringer forests from Nürnberg to Tabarz near Gotha and the company Manfred Schägner Spritzguss-Erzeugniss, before, and by all accounts via the sort of shady, opaque, process that underscores much of reality in the DDR, being produced in nearby Waltershausen by both Karl Ribarsch-Knopffabrik and Anni Friedrich. In the 1970s the two becoming one as VEB Plastspielwaren Waltershausen, a division of VEB Gothaer Kunststoffverarbeitung, and the brand name PLASPI.

Not to be confused with DDR LEGO, that was PEBE, and FORMO, the PLASPI Großblock system allowed for the construction of houses, for all high rise blocks, that near ubiquitous component of DDR construction, a concept take on from the inter-War Functionalists, or at least after the ending of the early 1950s Formalism Debate, and a concept which reflected as much the social and economic realities of the DDR as it did any innate conviction in the principle of industrial construction; and thus the Großblock system is/was not only a toy but also a means of normalising the Plattenbau as a central component of DDR housing policy, a propaganda tool for indoctrinating the young, or as Professor Leopold Wiel the, then, Director of the Institute of Structural Engineering at the TU Dresden noted in a 1971 letter to his colleague Peter Düsing, who in context of his PhD Thesis had been involved in the development of the PLASPI Raumelement system, "the kit is ideal for encouraging youths to take an interest in the development of industrial construction. It is contemporary because it takes into account important requirements of the unitary construction system."

Whereby the Raumelement system is a particularly interesting development of the Großblock construction system being as it is, in essence, shipping container-esque modules that can be individually internally configured and then stacked on top of one another to create housing blocks. Is, if you so will, a plug-and-play construction system. And thus represents, arguably, the sort of "important requirements of the unitary construction system" the likes of Wiel and Düsing were working towards, and which the DDR realised in plastic toy systems, but not in actual construction systems.

Beyond the presentation of PLASPI as a toy, as a component of the economic/commercial realities in the DDR and of the wider Bauhaus/DDR continuum, particularly pleasing is the provision of a table with PLASPI components that allows visitors, young and old alike, to freely experiment, and thus help one approach an understanding of the inherent logic and beauty of industrial construction systems compared to traditional brick-on-brick construction. Equally instructive are considerations on the piles of rubble surrounding the ruins on the play table, an all too graphic illustration of how Ostmoderne became Ostmarode, and the question if that must be? Was it inevitable?

From toy construction systems Inspired by Bauhaus moves on to consider real Modernist architecture. And Bauhaus's place in the wider developments of the inter-War years.

As part of the Bauhaus Weimar centenary celebrations a series of photographs by Berlin based photographer Jean Molitor of international Modernist architecture has been touring Germany; Inspired by Bauhaus presents a selection of Molitor's Bau1haus photos with a largely, though not exclusively, local connection.

The non-local context is illustrated by works such as, and amongst many, many others, Hans Scharoun's contribution to the Weissenhofsiedlug Stuttgart, Erich Mendelsohn's Petersdorff department store in Wrocław or the so-called Kenwood House in Nairobi by Ernst May. Works which also very neatly underscore that Bauhaus isn't/wasn't the only circus in terms of inter-War Modernist architecture: May, Mendeslsohn, Scharoun and the majority of the architects on show in Gotha having had no direct professional links to the Gropius school.

The more local context is illustrated by a surprising, and thus highly instructive, number of works including a house by an unknown architect on Gotha's former airfield, the former administrative building of the Gothaer Waggonfabrik, Richard Neuland's Am Schmalen Rain garden city estate on Gotha's southern outskirts and, and as arguably the principle focus of the presentation, the Conitzer & Söhne department store in downtown Gotha.

Realised in 1928/29 by Gotha born, Munich educated architect Bruno Tamme the Conitzer & Söhne building is presented through numerous documents, historic photos, a contemporary photo by Jean Molitor .... and by the work itself, just a couple of minutes walk from the KunstForum. Standing today amongst the relatively, let's say, eclectic, architecture of the area bordering Gotha's Neumarkt, it's hard to fully imagine how it must have fitted in amongst the narrow alleyways, timber-frame houses and royal palaces of historic Gotha: if there is just enough of that still visible to allow the most fleeting taste of the combination of protest and wonder with which it must have been received. Sitting much more easily with the peoples of the inter-War Gotha, we imagine, we weren't there, being the 1934/35 office building for the electricity concern ThELG, a charming brick work by Werner Issel, he of the Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus, sitting quietly and unobtrusively next to Gotha railway station.

Certainly more agreeable to the peoples of inter-War Gotha would have been a much older work, and a marginally older link to Bauhaus in Gotha, the so-called Haus zur Goldenen Schelle.

Constructed in 1599 on a corner of Gotha's Hauptmarkt, in 1870 the Haus zur Goldenen Schelle was bought by the brothers Emanuel and Abraham Ruppel who established within its timber-framed walls a small ironmongers business; an ironmongers which in 1894 became a metal fabricator in the city's Reinhardsbrunner Strasse, a metal fabricator producing small objects and household goods; and a metal fabricator which in 1929 employed Marianne Brandt as head of the consumer product development department: and thus opening one of Gotha's' better known, if as we're prone to opine, poorer understood, Bauhaus/Modernist connections and expressions. A story that is easily explained though a couple of napkin holders or bookends, but much more satisfyingly explained in the variety and depth of Inspired by Bauhaus.

Presenting a more or less chronological presentation of Marianne Brandt's three short years with Ruppelwerk Gotha the visual centrepiece of the showcase is a collection of Ruppelwerk products; products in all probability realised by Marianne Brandt, the provenance of early 1930s Ruppelwerk designs is not always equivocal, but it can be assumed they were all Marianne Brandt's work; products which in a before/after comparison very pleasingly indicates how Marianne Brandt transformed the Ruppelwerk portfolio: and products including a small clock from 1932 which, as noted previously, wouldn't have looked out of place in a 1950s Braun catalogue. Nor, in many regards would a small table top thermometer. And associations which pose the absolutely delicious questions of what if in the wake of her leaving the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung in East Berlin Marianne Brandt had followed the likes of a Herbert Hirche, a Wilhelm Wagenfeld, a Village People, what if Marianne Brandt had gone west: and for all what if in the mid-1950s Marianne Brandt had swapped the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung for the HfG Ulm. What if......?

A plaintive cry echoing from many of the products on display in Inspired by Bauhaus: products such as the numerous Tastlichte, a collection of table/bedside lamps where the whole foot is one large on/off switch, a stupidly, stupidly, simple development of lamp design technology, a development that saves the user faffing about in the dark to find a small switch, a development in which, in all probability, Marianne Brandt was involved and a principle updated in contemporary touch sensitive light switches; products such as the metal candelabras which, and as we noted from Four “Bauhausmädels” at the Angermuseum Erfurt indicate the translation of ceramic candelabras into metal, and that with just as much poise and grace; products such as the vacuum coffee percolator, one presumes a project conceived as a competition piece to Gerhard Marcks' Sintrax percolator for near neighbours Schott & Gen. in Jena, if a much more rustic work, an almost Brutalist work in which the workings are not only exposed but integrated into the experience, a thoroughly engaging and charming object; and the sort of work one still regularly sees as student projects, projects aiming to reclaim the process of coffee making from the anonymity of contemporary coffee machines. And a coffee percolator which as we noted from Ich bin ganz von Glas. Marianne Brandt and the Art of Glass Today at the Sächsische Industriemuseum Chemnitz bares remarkable similarities to a wind lantern that was presented in Erfurt... in Gotha they stand side by side and although having very different forms and functionalities, the basic idea is essentially the same, and we'd argue, with nothing more stable than our ignorance on which to build our claim, that the two arose from the same initial sketch.

In addition one can experience and enjoy, and amongst an array of objects, office accessories, money boxes, a delightful pop-up mirror, some joyous serving trays and a cacti stand, sadly not the glorious discombobulation presented in Bauhaus_Sachsen at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig, rather a much more reserved if every bit as thought through design, and one complimented by numerous catalogue pages full of cacti stands. We learn a lot in the course of our travels, that cacti were a big thing in the inter-War years is new to us. And something we sense we'll explore more next year. Watch this space.

And one can experience materials other than metal, or more accurately, can experience objects not exclusively crafted from metal, including objects which combine wood and metal and also, and an absolute highlight for us, a napkin stand with a metal base and glass napkin holder: for much as we adore Marianne Brandt's metal napkin holders, replace the metal with glass and the napkin becomes the decoration, allowing for an ever changing, active, adaptive, visual.

Complimenting the examples of Marianne Brandt's works are photos of Brandt both at work and at leisure, including one of her relaxing in what appears to be a thermal onesie while sat next to a cactus, and also a selection of correspondence, both as original copies and quotes, including those that indicate the obviously very complicated relationship between Marianne Brandt and the Ruppelwerk, correspondence that implies her attempts at updating and modernising the company's portfolio met with internal resistance. From whom and in which form is sadly not recorded, just one of a great many unanswered, unanswerable? questions surrounding Marianne Brandt, yet questions whose answers are important in helping us approach a better understanding of a designer whose biography can help us approach a better understanding of design in both inter-War Germany and in post-War DDR.

But for all the presentation very satisfyingly underscores Marianne Brandt's relevance as designer and tends to confirm the words of László Moholy-Nagy, the man who, against the general rule at Bauhaus Weimar, took her on in the metal workshop, and in who 1932 wrote to her with the opinion that, "es wäre wirklich an der zeit, dass ihre formungsgabe nicht nur unter den freunden anerkannt, sonder ausgenutzt wird"*

"It really is time that your talent was not only recognised by your friends, but fully utilised"

If there is one Bauhäusler who can inspire it is Marianne Brandt. As Gotha experienced. Even if it wasn't, necessarily, always, paying full attention.

Despite the very different nature of the three subjects presented, their spatial separation and for all the differing presentation formats, allow for an exhibition experience that remains fresh as one moves though it; one carries thoughts and impressions between the floors but the new impulses and new contexts keep them on their toes, never allowing them to fully settle.

And which in doing so allows not only for an easily accessible, engaging and entertaining exhibition and easily accessible, engaging and entertaining expansions of understandings of the scope and legacy of inter-War modernism, and the work and person of Marianne Brandt, and indeed for the development of new understandings, but for all an easily accessible, engaging, entertaining and informative introduction to inter-War Modernism as experienced in and by Gotha.

And the understanding that the historical veins that flow through Gotha aren't just those of blue blood.

✔

Inspired by Bauhaus - Gotha Experiences Modernity runs at the KunstForum Gotha, Querstraße 13-15, 99867 Gotha until Sunday December 29th

* For all fans of German grammar, the original is also all kleingeschrieben... Bauhaus eben....

Full details can be found at www.kultourstadt.de/inspiriert-von-bauhaus (German only)