Our Mondo Contemporaneo is a very unhappy, unsatisfying, unrewarding, dark, place.

Should we perhaps all consider a move to the colourful, dynamic reverie of Mondo Mendini?

At the Groninger Museum you can undertake a trial visit...............

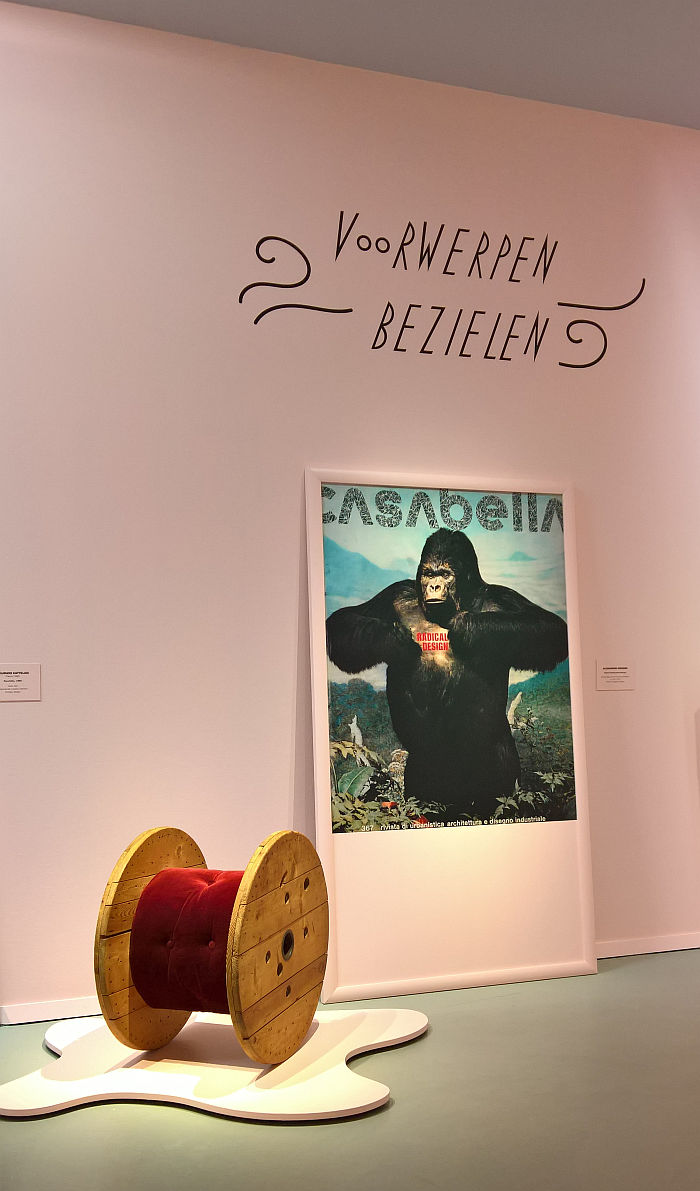

Born in Milan on August 16th 1931 Alessandro Mendini studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, graduating in 1959 and moving on to join the studio of Marcello Nizzoli, where he not only continued his development as a practising architect, but through Nizzoli and his varied contacts developed as an architectural theoretician, for all a theoretician on architecture's social and cultural values and responsibilities. And a development that saw him leave architectural practice in 1970 to take up the post of Editor in Chief of the avant-garde architecture and design magazine Casabella, and also become one of the leading theoreticians of 1970s Radical Italian Design, including roles in the Global Tools collective and Studio Alchimia, roles which brought him into contact with like-minded architects such as Ettore Sottsass, Gaetano Pesce, Andrea Branzi or Michele De Lucchi.

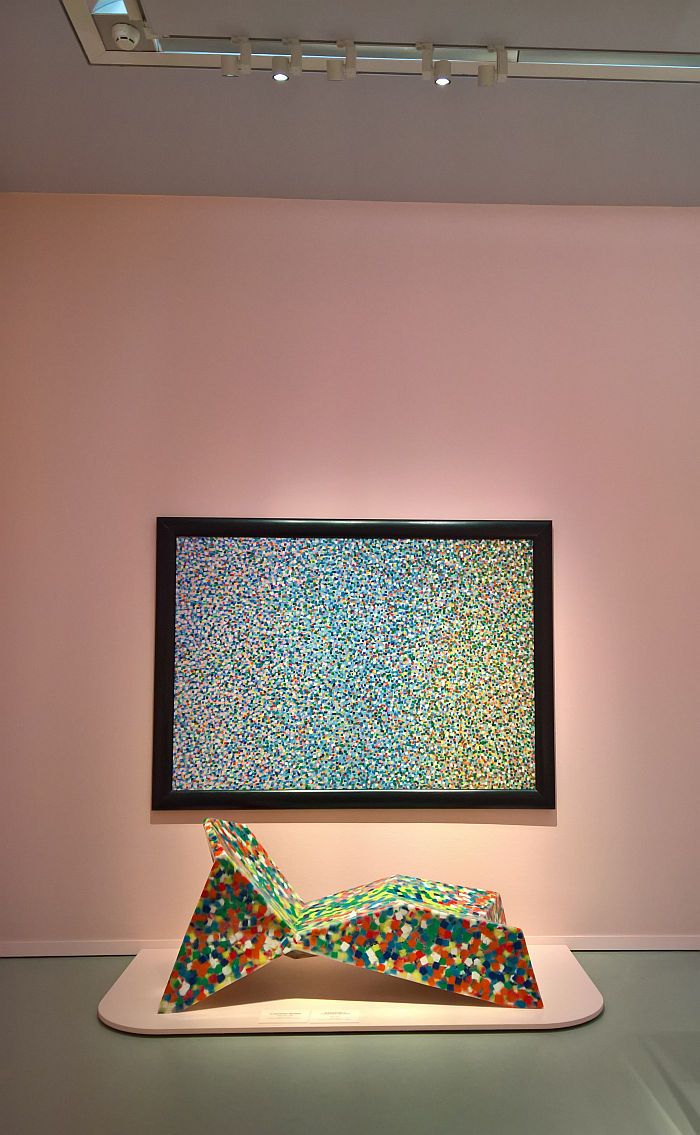

The 1970s also saw Alessandro Mendini take his first steps as a practising designer, initially through one-offs and limited edition pieces including Sedia Scivolavo, an exaggerated and imbalanced representation of a simple wooden chair; Kandissi, which re-imagines a sofa in the abstract expressionism of a Wassily Kandinsky; or Poltrona di Proust which re-imagines a rococo armchair in the Pointillism of a Paul Signac, and a one-off subsequently reproduced as a serial product by manufacturers such as Cappellini or Magis, thus helping it become, alongside the numerous Memphis creations, one of the best known examples of Italian Postmodern design.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s Alessandro Mendini remained an important figure in Italian, and global, design, both through one-off and limited edition pieces, including the Maracatu sofa and armchair developed in context of the, sadly defunct, Vitra Editions programme, and also through commercial cooperations with manufactures as varied as, and amongst many others, Swatch, Zanotta, Glas Italia or, and arguably most famously, Alessi. And also remained important as a theoretician and mediator through both his various editorial positions with magazines such as Domus or Modo, and also as a professor and educator in Milan and further afield.

In 1989 Alessandro Mendini established Atelier Mendini in Milan with his (architect) brother Francesco, and where some thirty years after graduating as an architect, his biography as a practising architect really begins.

In addition to works such as the Torre Paradiso in Hiroshima, numerous underground stations in Naples, or the Steintor tram stop in Hannover, Alessandro Mendini's most popularly known work is arguably the Groninger Museum, a project commissioned in 1988 and opened in 1994 as a disorientating discombobulation of colours and shapes standing self-confident and self-assured in Groningen's Verbindingskanaal. And a work realised in cooperation with those other distasters of the quadratic, the monotone, the expected, Philippe Starck, Michele de Lucchi and Coop Himmelb(l)au.

By way of celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Groninger Museum's opening Alessandro Mendini was asked if he would like to curate a self-retrospective. He did, and decided not only to include work by himself in the exhibition, but work by other designers, architects and artists he admired and/or who were in one way or the other an inspiration and/or influence on his journey. The result is Mondo Mendini.

Alessandro Mendini sadly died on February 18th 2019 in his native Milan, thereby making the Groninger Museum's exhibition not only a very personal retrospective, but an equally personal celebration of the man, his work and his contribution to understandings of architecture, design, form, function and ornamentation.

The first Alessandro Mendini exhibition in Groningen was staged in 1988, largely by way of introducing the good citizens of Groningen to the radical Italian who was about to build something, well, radical, in their canal. Twenty-five years later Mondo Mendini is in many regards also about introducing Alessandro Mendini, introducing Alessandro Mendini to a new public, a public who may be familiar with images of one or the other of his works but not with his wider oeuvre and place in architecture/design history; an introduction undertaken with the benefit of an extra quarter century's worth of works and points of inquiry; and an introduction narrated by Alessandro Mendini himself through eight short chapters each themed around an individual essence of his work, including Provoking the Arts, Freeing Shapes or Experimenting With an Eye to Art, the latter featuring works as varied as a collection of 19th century models of fruits by Francesco Garnier Valetti, Walt Disney characters and the remains of Lassù, two wooden chairs Mendini built. And then set on fire as a reflection on transience, on life and death, creation and destruction. And which are therefore presented as charred remains. One more so than the other.

Parallel to its reflections on the essence and nature of Mendini's oeuvre, Mondo Mendini also takes the visitor through some of those movements and moments in art, design and architecture history which not only had an influence on Mendini and his work but movements and moments to which Mendini, in many regards, contributed to and helped evolve, including, and as arguably one of the most popularly known influences on Mendini's work: Neo-impressionism. For all as expressed in the Pointillist approach of a Paul Signac, an artist represented in Mondo Mendini by his 1899/1900 work Mantes, and an influence represented in Mondo Mendini on the one hand through Mendini's many mosaic pieces, the small colourful tiles standing proxy for the spots of paint employed by Pointillist artists, and on the other hand by works where the Pointillist spots of paint are represented by, well, spots of paint, including Poltrona di Proust, presented as the 3m tall Poltrona Monumentale di Proust, an almost Alice in Wonderland-esque object, if a much more understated object than it sounds, and one which not only eloquently represents Poltrona di Proust and the way the applied decoration, and much as the Pointillists reduced landscapes down to a decipherable blur of colour, blurs the constructive and formal elements, while simultaneously raising ornamentation from the decadence derided by an Adolf Loos to something more noble, something which, and as Louis H Sullivan once argued of ornamentation on pure and simple architecture, allows the original chair to "appeal with redoubled power."1 But also in its juxtaposition between the ostentatiously impractical and the joyously obvious stands as a nice metaphor for much of Mendini's canon.

As does a 16th century suit of armour which neatly represents what the curators refer to as Mendini's belief in the unbroken continuation of a handcraft tradition since the Renaissance, part of that helix on which we are all riding, and a handcraft tradition reflected in numerous works by Mendini and others, including a metal bowl by Josef Hoffmann with a pair of twisting, winding, handles that may lack the reduced rationality one normally associates with Hoffmann but which represent every bit as unequivocal, clear and direct a line; and a handcraft tradition further represented in Mondo Mendini through examples of Folk Art including a number of anonymous, undated 19th century objects, a collection of 1930s works by Fortunato Depero and also more contemporary interpretations of Folk Art including a truly outrageous, if slightly sinister, carousel of Alessi objects. A functioning, spinning, musical, and thus slightly sinister, carousel of Alessi objects.

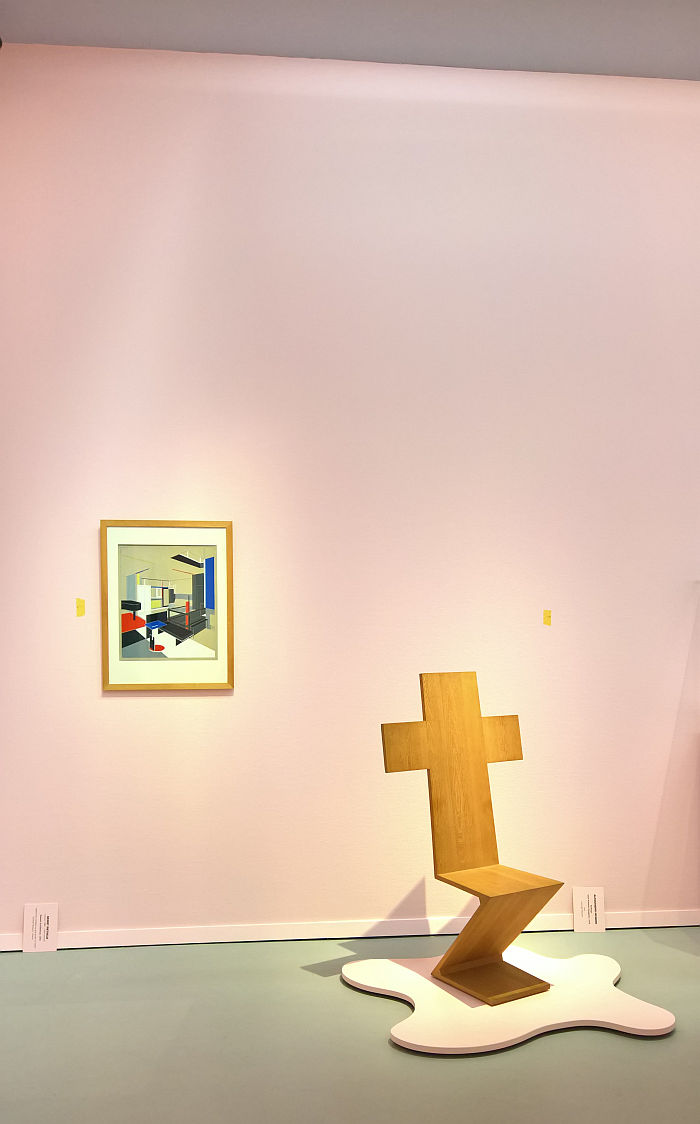

As one would expect of an exhibition focussing on the world of a leading protagonist of Postmodernism, and of an exhibition compiled by said protagonist, Mondo Mendini features several expressions of early 20th century modernist creativity. On the one hand Bauhaus, a school whose rationality and functionalism Mendini stands as an antithesis of, yet in the abstraction of an Oskar Schlemmer or a Wassily Kandinsky Mendini was, as the exhibition helps elucidate, very much of a Bauhaus; on the other hand by the Bloomsbury Group of early 20th century English intellectuals and artists who pushed a reformist, humanist, egalitarian, agenda and are represented in Mondo Mendini by Virginia Woolf, a writer of whom Mendini was, we learn, a huge fan and who in the exhibition stands in direct dialogue with Kandinsky. And while we're sure Virginia Woolf would have a good few things to say to Wassily Kandinsky, we can't help imagining she'd much rather be in conversation with Kandinsky's colleague Oskar "where there is wool, there is a woman" Schlemmer, or indeed Allen Jones, he of the semi-naked female mannequin bondage chair, and represented in Mondo Mendini by a pair of equally contentious and sexually ambiguous scissors. Yes, in the hands of a Postmodernist even scissors can be contentious and sexually ambiguous.

On the all too rare third hand Mondo Mendini also underscores the influence of the early 20th century anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner and the separation of the physical and spiritual world, and the associated emancipation from the restrictions of existing forms and norms; separation and emancipation continued on the improbable, believed mythical, fourth hand, by Surrealism.

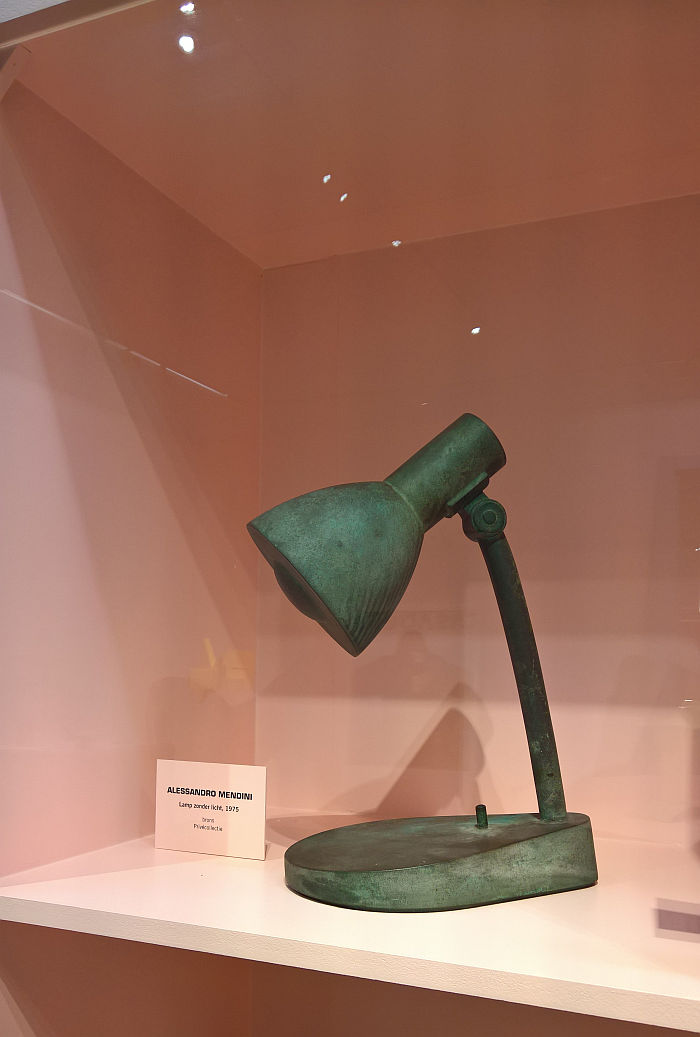

Admittedly, yes, we did view Mondo Mendini (very) shortly after viewing Objects of Desire. Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today at the Vitra Design Museum and so were still very much tuned in to a Surrealist expression; however, on this occasion, it wasn't just us. The presence of the 1932 painting Annunciation by Alberto Savinio standing as representative of a work by Savinio that hung in the Mendini childhood home, and thus highlighting an early exposure to Surrealism, while works such as, and amongst many, many others, the Readymade cable roll chair Rocchetto by Maurizio Cattelan, Mendini's own Readymades such as the Alessi corkscrew Anna G or, in many regards, Kandissi & Poltrona di Proust, plus his Anti-readymade Lamp without light, a work remiscent of the 702 bedside table lamp developed in 1928 by Marianne Brandt & Hin Bredendieck for Kandem, just in solid bronze, and thereby poking a little fun at the rhetorical monuments erected to Bauhaus, tending to underscore the inextricable link between Surrealism and Postmodernism. And also how Alessandro Mendini applied the reason that André Breton postulated in his Surrealist Manifesto may be needed to be applied to the power of imagination, and in doing so helped develop and evolve Surrealism, made it somehow less abstract, less quixotic, and thereby more fun, more humane.

Based around an exhibition design conceived by Alessandro Mendini to be an experience akin to arriving in a city for the fist time, arriving with no map and simply wandering around, making chance discoveries and thereby getting to know the city without any advance preconceptions, without the dogma and pressure of the tourist gaze, Mondo Mendini allows not only for just such a level of surprising, unexpected, and thus all the more enjoyable and rewarding discoveries, but also means that as an exhibition it can be viewed without any prior knowledge, the concise trilingual Dutch/German/English texts setting the scene of the various chapters, the exhibits doing the rest.

A non-chronological, non-hierarchical, and thereby very-Mendini exhibition; very much non-Mendini is the monotone, light pink, colour scheme that runs throughout the exhibition: the splashes of colour, mosaic and abstraction of the displayed works being more than enough to illuminate Mondo Mendini.

But enough illumination to make Mondo Mendini a place to which we should all decamp?

In many regards the answer to the question begins outside and the view of the Groninger Museum. A challenging view. Not uninteresting. Not unpleasant. Certainly every bit as eclectic and engaging as the architecture of Groningen's Hanseatic old town. But challenging. Largely, we'd argue, because it is an expression of a moment in the (hi)story of architecture and design that is largely, popularly, understood as being purely and exclusively visual. That it is all about the colours and the shapes. And that can be challenging. As can the works by Alessandro Mendini on show inside.

However the juxtaposition of Alessandro Mendini's work with that which Alessandro Mendini admired and/or inspired him, the juxtaposition with creatives and artisans who he admired and/or who inspired him, helps one approach not only a better, more grounded, understanding of the man and his work, but also allows Alessandro Mendini to exist as a conduit by which to explain the course of one strand in the development of architecture and design since the 1960s, by which to explain the development of one approach to aesthetic understandings, and also by which to explain the development of an understanding of functionality that goes beyond a purely practical, tangible, usability and adds something more emotional, more sensory, more discursive, makes design as much a branch of applied linguistics as of applied arts, and which makes design, in the words of Mendini's contemporary Ettore Sottsass, "sensual and exciting." 2

And explains that although such is regularly expressed through colour and shape, the colours and shapes are but a means of expression, not an end in themselves.

And in doing so helps explain that Mondo Mendini isn't a physical, tangible, good, far less a strict aesthetic principle, but that Mondo Mendini is an understanding of the relationships between objects, between ourselves and the objects with which we surround ourselves, between ourselves and the environment in which we exist, and for all is a way of viewing the world, a way of viewing our Mondo Contemporaneo.

Which we guess makes the Groninger Museum's exhibition less a trial visit and more a telescope, or perhaps more accurately, a kaleidoscope...........

Mondo Mendini runs at the Groninger Museum, Museumeiland 1, 9711 ME Groningen until Tuesday May 5th.

1Louis H Sullivan, Ornament in Architecture, The Engineering Magazine, August 1892, reprinted in Louis H Sullivan, Kindergarten Chats and other writings, Dover Publications, New York, 1979

2Unattributed, or at least we can't find the original source....

Full details can be found at www.groningermuseum.nl/mondo-mendini PS. In interests of clarity, as is the nature of these things we visited Mondo Mendini before the official opening, and before numerous wall panels had been mounted. Thus in our photos many of photos, paintings et al standing on the floor, are now hanging on walls. Also the lighting wasn't finalised.