On May 14th 2019 the European Court of Justice ruled that all employers are required "to set up an objective, reliable and accessible system enabling the duration of time worked each day by each worker to be measured." 1

On July 15th 1855 Johannes Bürk was granted a patent for just such a system.

A system which, as the Uhrenindustriemuseum Villingen-Schwenningen's exhibition Time, Freedom and Control – The Legacy of Johannes Bürk explains, paved the way, certainly in spirit, for many of the developments in terms of recording, monitoring and managing time which not only developed in the course of the industrialisation of the late 19th/early 20th century, but were imperative to industrialisation's success.

And which continue to inform and define our post-industrial society.

Back in the day time had little popular relevance. The sun rose. The sun set. Between the two one did what needed doing. Time as such didn't exist. Where time did have a relevance was in regulating and defining daily routines in religious orders, primarily in context of the Christian faith; initially in cloisters, monasteries, et al and subsequently, in course of the spread of mass Christianity, amongst wider society. Clocks on church towers don't exist as a philanthropic public service, rather are, in conjunction with the peeling of bells, about ensuring a correct and orderly attendance of the flock.

And this use of time to regulate and define the daily life of the masses became mirrored in the development of the new religion of industrialisation, a development that necessitated an accurate, and for all regulated, measuring of time; on the one hand for the transportation of its finished goods and raw materials and on the other for the operation of its factories, for all in ensuring a correct and orderly attendance of the flock workers.

Necessities which not only spawned new developments in how time was recorded and monitored, but also led to evolutions in our relationship to time, to the role of time in our everyday lives; developments and evolutions to which, as Time, Freedom and Control – The Legacy of Johannes Bürk neatly elucidates, the Schwarzwald clock industry played a central role.

Clocks, or perhaps better put, clockwork technology, has been developed and produced in the Schwarzwald since around 1700, and has/have contributed fundamentally to the economic and social development of the region; the, then, village of Schwenningen, for example, doubling from 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants in the century between circa 1780 and 1880 as ever more workers migrated from across Europe deep into the Schwarzwald.

Amongst the leading protagonists in the development of the Schwarzwald clock industry was Johannes Bürk. Born in Schwenningen in 1819 as the son of a shoemaker, Johannes Bürk initially established himself as an author and publisher before in 1849 he was appointed Schwenningen's Schultheiss, mayor. Among the myriad problems with which Johannes Bürk occupied himself as Schultheiss was the monitoring of the town's nightwatchmen: important as the nightwatchman was in the mid-19th century, as Time, Freedom and Control explains, it wasn't a particularly highly regarded position and thus wasn't a job always undertaken with the devotion and attention the responsibility demanded. Monitoring nightwatchmen's activity was therefore considered imperative. But how? Not least because, by definition, nightwatchmen work at night. And mobile.

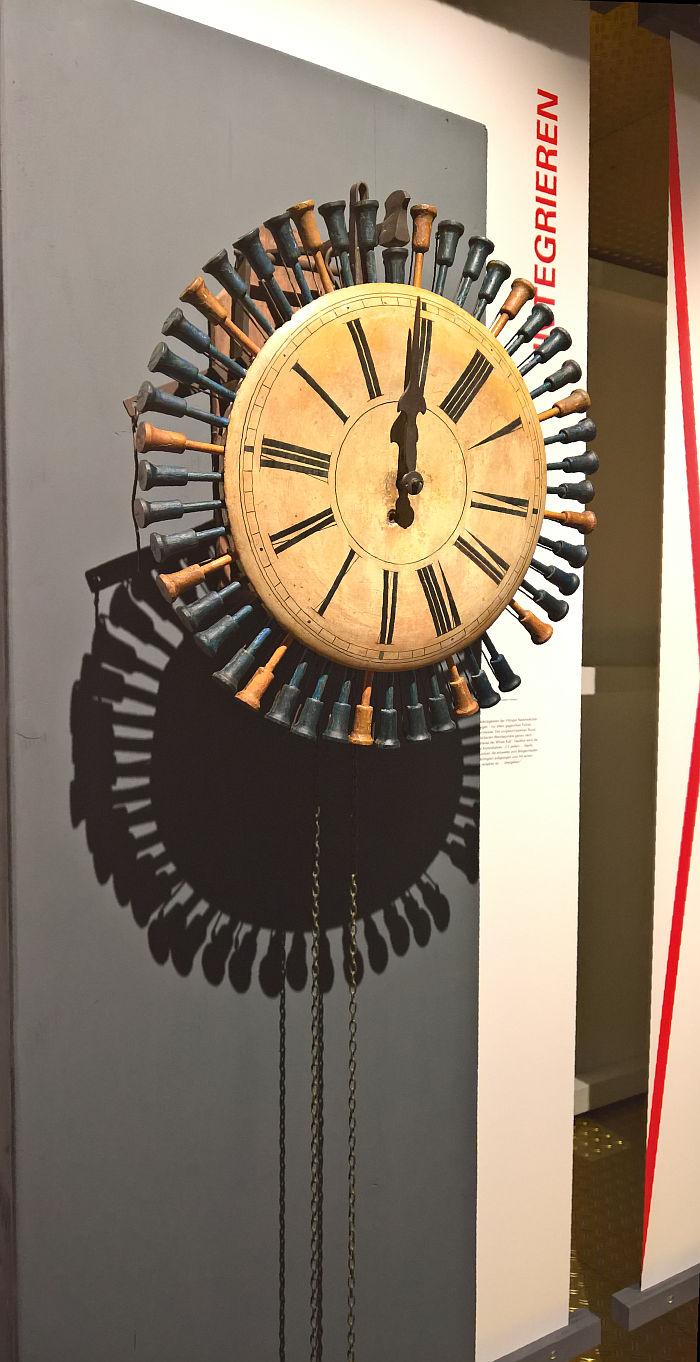

And while, yes, inarguably, raising the status and regard of the nightwatchman within mid-19th century society would have been one possible solution, taking the (Leninist) premise that while trust is good, control is better, Johannes Bürk sought a technical solution, and in 1855 devised with his so-called Nachtwächter-Kontrolluhr [Nightwatchman Control Clock] a solution as intuitive as it is/was stupidly, stupidly, simple: a strip of paper turns on a clockwork mechanism inside a pocket-watch sized object, and which nightwatchmen stamped through the use of a series of unique keys distributed along the course of their route. And thus a system which allowed the presence of a nightwatchman to be unequivocally recorded at a specific place at a specific time. Thereby allowing the activity of a nightwatchman to be monitored.

And not just nightwatchmen; rather, and as discussed in the course of Time, Freedom and Control, a system which enabled a wider monitoring of society.

Opening with a brief, scene setting, exploration of the social, economic and political situation in 19th century Schwenningen, and the briefest of brief introductions to the person of Johannes Bürk, Time, Freedom and Control moves quickly on to its main discussions: the central role of our ability to record and monitor time in the development of industrial societies, and the tension that exits between the ability to record time as an enabler of individual freedom and the ability to record time as an agent of institutional control.

To this end Time, Freedom and Control follows a chronological path from 1855 to today, or more accurately put, two parallel chronological paths. On the one side a general discussion of how, following on from the use of time to monitor nightwatchmen, time has been subsequently harnessed and employed to discipline, standardise and flexibilise society, an argument explored through objects such as, and amongst others, an early, stationary, clockwork device for monitoring nightwatchman and which neatly underscores the challenge taken on by Johannes Bürk and the grace with which he resolved it; an alarm clock as both an example of one of the changes industrialisation brought to our daily lives, one of the most tangible checks industrial society places on individual freedoms, and also a central product in the history of the Schwarzwald clock industry, an industry which not only profited from increasing industrialisation, but contributed to its wider spread. And the Frankfurter Küche, a project which, as discussed in our Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky design calendar post, was based on Schütte's time and motion research in context of her work for the Vienna Siedlerbewegung: "the time you need for each action should be measured with a stopwatch, every step should be counted and put, so to speak, on the scales", she opined in 1921, and that with the aim of deducing, "if something for which one needed ten movements would be possible with eight, and so on…"2 The popularity in the early decades of the 20th century of monitoring time for the purposes of standardisation being accentuated by videos of time and motion studies undertaken by Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, and by a mid-1930s kitchen clock: an apparently innocuous, arguably aesthetically pleasing object, but which as the curators note represents the fact that even in the kitchen, "every minute was important." A minute saved in household chores being a minute more freedom, but a minute saved through strict regulation.

Thoughts which take us back not only to 1921, Margarete Schütte and the inter-War modernists unyielding, unquestioning, fascination with standardisation and therefore an alternative perspective on the legacy of that period, but also to the exhibition Politics of Design. Design of Politics at Die Neue Sammlung Munich, and Friedrich von Borries opinion that Design Manipulates, Design Disciplines.

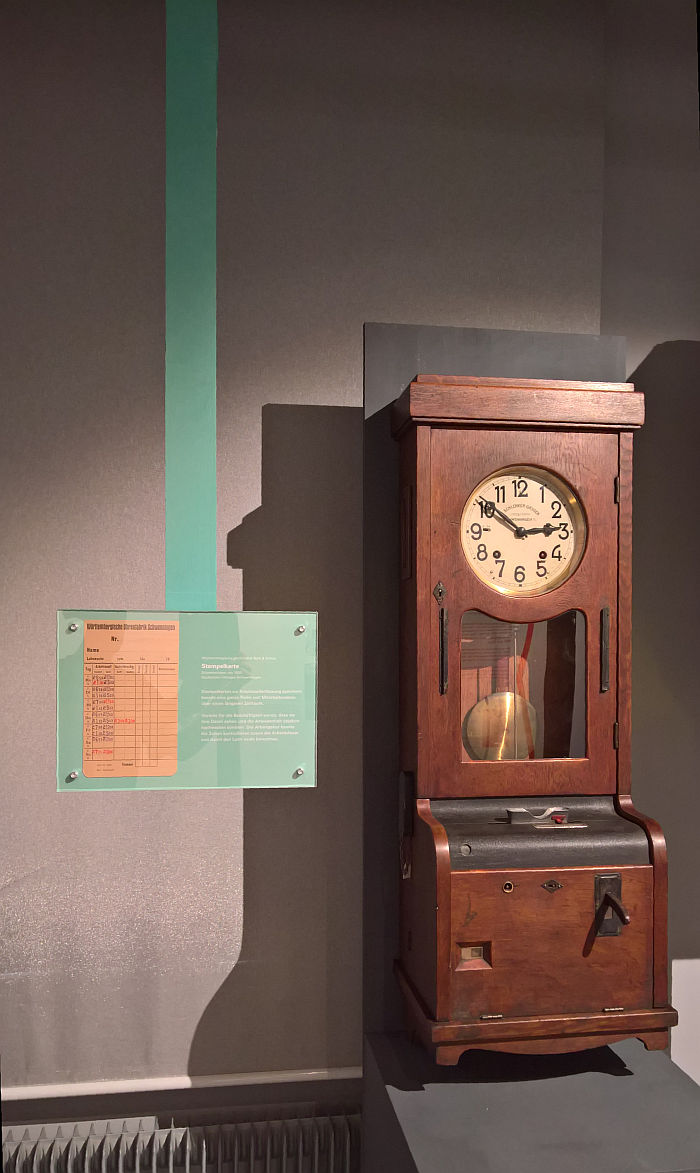

Alongside such general discussions, and also very much in the spirit of design disciplining, design manipulating, design forming, Time, Freedom and Control presents the contributions of the local Schwarzwald clock industry to the developments of the period, for all in context of employing time as tool in the development of industrialisation, and including a so-called Radialapparat from ca 1900, an early version of the punch clock, and specifically a model developed by Binghamton, New York based Bundy Manufacturing Company and produced under license in Schwenningen by Johannes Bürk's Württembergische Uhrenfabrik, WUF, and, thus a reminder that WUF were much more than the Nachtwächter-Kontrolluhr but were throughout the 20th century leading international players in the development of time recording and management systems; a 1950s Arbeitsschauuhr which records the amount of time a worker spent on a particular job and thereby allowing for a monitoring of efficiency and a more detailed cost analysis, and thus cost efficiency analysis of the individual worker; or the Kienzle 6600, an ungainly looking beast which allowed for the semi-automated calculation of flexitime hours worked, flexitime being arguably the most tangible freedom documenting time has brought (post-)industrial society. If a freedom that comes with a goodly degree of central control.

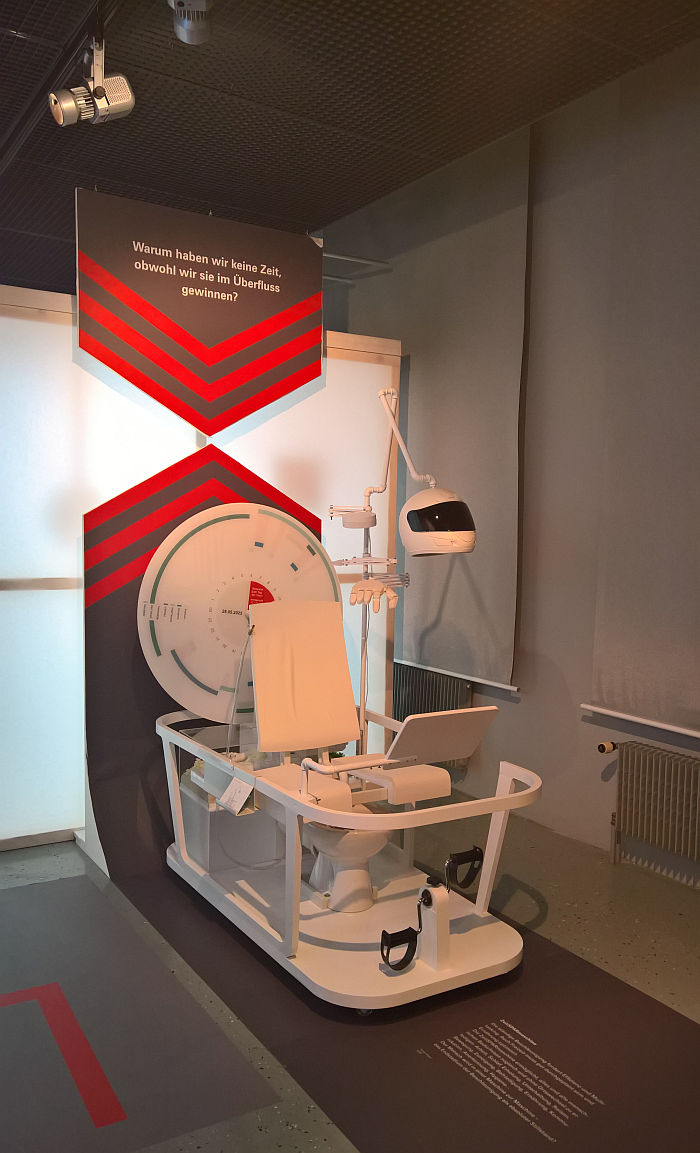

Both paths end with contemporary approaches towards optimising our management of time: the industry timeline ending, outwith Villingen-Schwenningen, with a discussion on the iPad as representative of new ways of working and the ZeitSPARmaschine by Freiburg based designer Tanja Unger: a future concept which foresees humankind relinquishing in the interests of maximally optimised time management all its tasks to a machine. And in doing so becoming a machine.

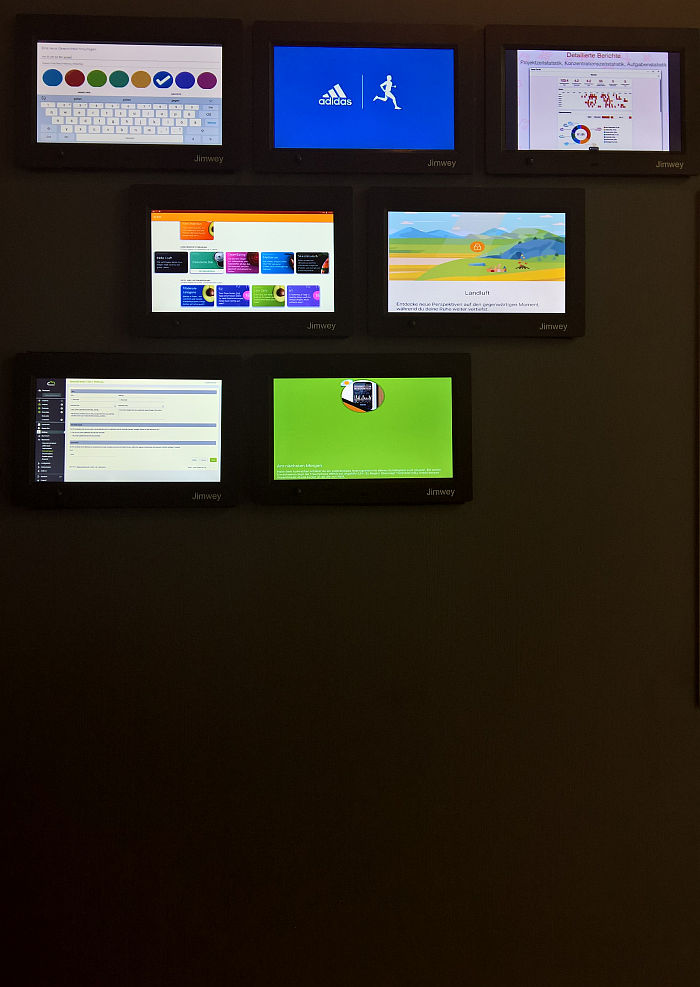

The general side featuring a collection of apps including, and amongst many others, the Habitbull Habit Tracker, the Runtastic fitness tracker and the Billomat accounting app, and all designed with the aim of achieving maximally optimised time management........

And which one day will make machines of us all?

The comparison is perhaps a little too simple, but nonetheless valid, and does neatly focus your attention on the century and a half of standardisation and optimisation of time monitoring and recording we've undertaken since Bürk's Nachtwächter-Kontrolluhr, and for all the purpose of our continual striving for optimised time management.... what do we actually want to achieve? Why do we want to achieve it? And where may it lead us?

Questions that are extremely apposite in our contemporary society where the monitoring and recording of our time is increasingly not only in context of our working lives, but of our private lives. Achingly painful as an early morning alarm may be, arguments can be made for it in context of a functioning industrial society, and equally arguments made that we all benefit from a functioning industrial society, and thereby from early morning alarms. But where is the justification of recording our private moments and movements? Where is the justification in those swathes of data we send every day to California and which record our presence at a specific place at a specific time every bit as unequivocally as Johannes Bürk's Nachtwächter-Kontrolluhr once achieved? And over which we have as much control as a 19th century nightwatchman over his time data.

Johannes Bürk's intention was to ensure the good folks of Schwenningen were safe in their beds, and arguably he achieved that. And he could do no more with the collected data than ensure the nightwatchmen were doing their rounds as prescribed. Society, industry, technology, have evolved since 1855 and much as our contemporary technology may be beneficial, certainly may appear to be as philanthropic as a church clock, there is however always a pay off. And a very real risk to our freedom, a risk of an unsolicited control. Is that something we can/should/must accept? Are the benefits of monitoring every aspect of our daily lives large enough to justify the pay off and risks? Must every optimisation lead to a further optimisation? How will our unyielding, unquestioning, fascination for optimising our time leave the balance between personal freedom and institutional control in 10, 20, 100 years time?

And questions that are extremely apposite in our contemporary society of flexitime and home office, arrangements which may allow us all a degree of freedom in where and when we work, but in doing so also mean we are effectively always at work; the melting of the borders between home and office leading to emails being answered in bed, preparation for meetings being undertaken in the train on Sunday afternoons, business calls being answered in the supermarket, et al. The factory worker of the industrial economy had/has to clock in and out, but in is in and out is out. The factory worker of the service and digital economies doesn't clock in or out, and therefore is permanently in and out.

Which was part of the motivation behind the Spanish trades union's lawsuit that led to the European Court of Justice's ruling, to ensure that all that time in bed, on the train, in the supermarket is recognised and honoured as work time. But is that the solution? Does that not lead to even more control? To recording ever more precisely our daily movements to ensure the "reliability" demanded by the ECJ? The Nachtwächter-Kontrolluhr only recorded the nightwatchmens' position at specific moments in the night, not what they did in-between, are we happy to have that in-between recorded? Or do we not win more personal freedom if we simply go the office Monday to Friday, 9 to 5? Who actually benefits from flexitime and home office?

Whereby it's interesting to note that whereas in 1855 employers were keen on monitoring their workers, in 2019 they are less so. Or put another way, whereas in 1855 employers assumed the workers were slacking, today one gets the impression, certainly from the critical reaction to the European Court's ruling, that many employers suspect there may be a lot of unpaid overtime being undertaken. And which they'd rather not know about. Rather not have monitored and recorded. Certainly would rather not pay for. And which posses fascinating questions concerning the systems contemporary Johannes Bürks will develop in response to ECLI:EU:C:2019:402. Not least how much of it will be developed in California. And how much will be cheerily pitched as helping us optimise our time management.

A bijou exhibition, but one which in no way suffers from its spatial restrictions, Time, Freedom and Control, through explaining the history and development of time recording and time management very neatly, and very inconspicuously, leads one to question our relationship to time, and for all to understand that in our contemporary world time exists as a resource, and thereby a source of power and influence. That it isn't always understood as such being in many regards a consequence of the way in which the developments documented in the exhibition have conditioned us to accept the control of our time as a normal, natural, state of affairs, and therefore leading us not to question the limitations such a control places on our freedoms. Or perhaps better put, to fail to understand that one should, must, question the balance between control and freedom implicit in the recording and monitoring of time. Because it is always a balance.

Time, Freedom and Control is an invitation, an admonishment, to reconsider our understanding of time, freedom and control. To question who controls time? Need that be so? Can we influence things? Do we need to monitor and record time? Or in doing so do we simply become servants to time rather than mastering time? Have we over optimised? What's wrong with letting the sun rise, set and between the two doing what needs doing?

Time, Freedom and Control – The Legacy of Johannes Bürk runs at the Uhrenindustriemuseum, Bürkstraße 39, 78054 VS-Schwenningen until Sunday March 1st.

1http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=214043&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=req&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=7732645 Accessed 05.07.2019

2Grete Lihotzky, Einiges über die Einrichtung österreichischer Häuser unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Siedlungsbauten, Schlesisches Heim, Jahrg 2, Heft 8, August 1921, 217 - 222

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.uhrenindustriemuseum.de (German only)