The German town of Boppard sits on two of the most pronounced and prominent curves on the Mittelrhein.

Can it be a coincidence that Boppard's most famous son, Michael Thonet, is most popularly known for his curving bentwood chairs?

Can it really be a coincidence?

Possibly. Almost certainly.

What is less contentious is that the flow and meandering of first Michael Thonet's creativity and vigour and subsequently that of the company Thonet has carved its mark not only on the Rhenish Massif furniture design and on understandings of furniture, but also the furniture industry, from production to sales and distribution.

With the exhibition Thonet & Design the Neue Sammlung Munich embark on a voyage along some 200 years of Thonet design (hi)story.

The Mittelrhein [Middle Rhein] on which Boppard stands is a region rich in legend and mythology, a compendium of fables to which, in many regards, the story of Michael Thonet could easily be added. Were it not for that fact that unlike those of the "Blind Archer from Sooneck", the "Monks of Eberbach Abbey" or the "Fair Maiden of Lorelei", it is one supported by tangible evidence.

The tale of "The Carpenter Who Bent Solid Wood", begins in 1819 when Michael Thonet opened his first workshop, or perhaps more accurately, inherited that of his father Anton, a man who although originally a tanner, at some, unknown, point switched, fortuitously for history, to carpentry; and while the exact date of the founding of Michael Thonet's first workshop isn't known, the location is, between the contemporary Steinstrasse and Pützgasse in the so-called Balz, a compact, narrow-laned quarter of Boppard, pressed hard against the city wall.

Following a decade engaging in standard, if, according to the legend, very competently realised, carpentry pursuits, from around 1830 Michael Thonet began experimenting with moulding glued strips of wood veneer; a process known, for example, in the production of musical instruments or long bows, but relatively new in terms of furniture, one of the first to successfully accomplish such being the Belgian cabinet maker Jean-Joseph Chapuis at the turn of the 18th/19th centuries.

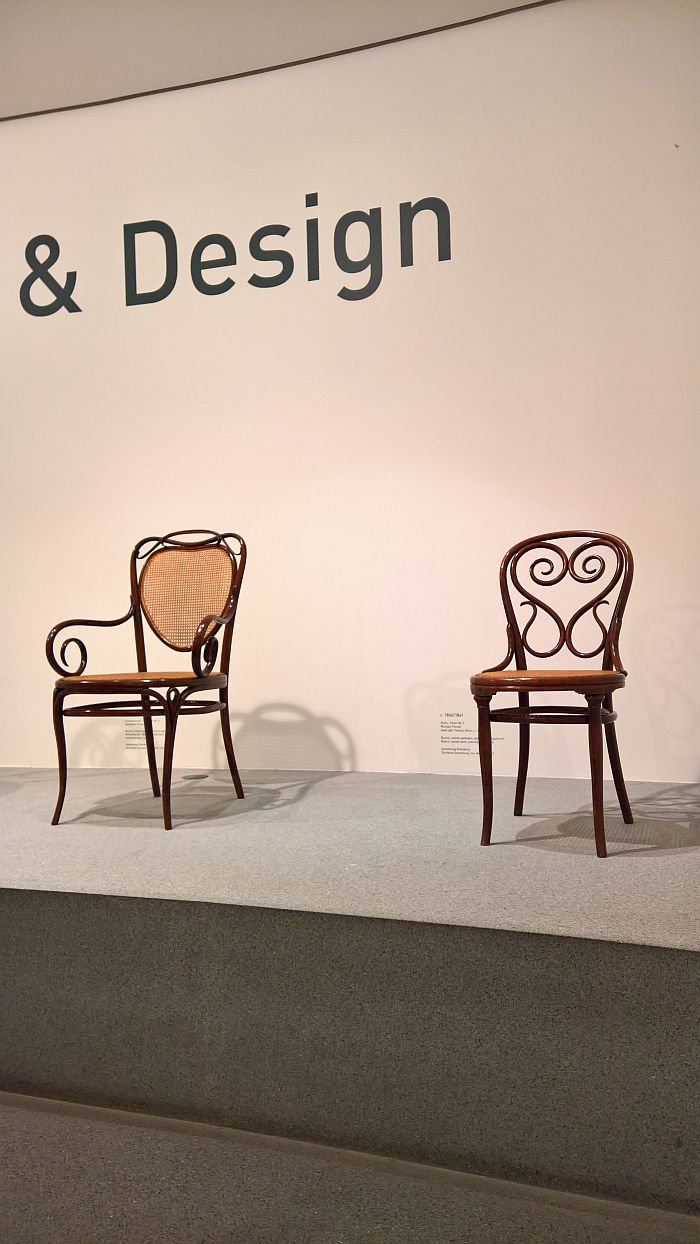

From Michael Thonet's own experiments arose in ca. 1836 the so-called Boppard Chair, a work which, logically, opens Thonet & Design, and a work which although formally alluding to what would/does come, is in may regards more interesting for a further herald it brings forth: a construction principle based around pre-fabricated components, and a principle which would become central to the development and success of Thonet's (future) company. And thus as a work the Boppard Chair wonderfully embodies the contribution to and connection between Thonet & Design. That Thonet was Design before Design was a thing.

In 1837 Michael Thonet, together with the Boppard pharmacist Martin Genius, acquired the so-called Michel Mill, an object close to Thonet's workshop, if outside Boppard's city wall, and where in addition to the establishment of a larger workshop, Thonet and Genius began with the production of glues; thus not only allowing Michael Thonet an independence for his furniture work, and, one would presume, in cooperation with Genius, to develop glues appropriate to his needs, but also established a second pillar on which to support his business.

A business that was obviously going very well, records for 1841 recording Michael Thonet as one of the highest taxed, and thus, presumably, richest, traders in Boppard; shortly afterwards he become one of the poorest, or at least most financially challenged, when, and as previously discussed, the debts accrued in the course of his numerous patent application processes became due.

But Boppard is on the Mittelrhein, a land of legends, myths, wonders and castles, one of which, Johannisberg sits a little upstream form Boppard and where in 1841 Fürst Clemens von Metternich, the then Austrian Chancellor idled, and who, having seen examples of Thonet's works in an exhibition in Koblenz, invited Michael Thonet to Johannisberg to discuss his work in more detail. Impressed by what he saw, and for all heard, Metternich advised Michael Thonet to move to Vienna, where he promised him his support. An offer Michael Thonet sagely accepted.

The Rhein as it flows through Boppard may be as pleasing as the Danube in Vienna, and both are regions of viticulture, with a loyalty to their local wines, but that is where the Boppard/Vienna comparison ends, if indeed it can even be considered to have begun, yet despite their disparity both Boppard and Vienna are of equal importance in the Thonet (hi)story.

That we've discussed the Michael Thonet biography in numerous previous posts we refer you dear reader to them; in Thonet & Design the early Viennese biography can be followed through numerous chairs developed, together with the English architect Peter Hubert Desvignes, in context of interior design commissions for the Liechtenstein and Schwarzenberg palaces, and also by works developed by Thonet alone, but clearly derived from such Desvignes collaborations, including the Nr 4, that work with which Michael Thonet first achieved a wider public, and for all the Nr 14, the contemporary 214, and a work whose success not only allowed for the laying of the foundation on which the company subsequently grew, but also, more or less, and simplifying to the point of inaccuracy, a work which through its use of pre-produced, standardised, components in a production line system involving trained, but unskilled workers, and on the basis of solid wood bending, effectively marks the start of both large scale industrial furniture production and global furniture distribution.

Reduced, unassuming and resolutely calm, the Nr 14 may be. But don't underestimate it. Which yes, and as with all good Rheinland tales, does sound like a metaphor......

In context of Michael Thonet's rise and success in Vienna one must however always remember the nature and realities of the period, the environment in which works such as the Nr 4 and Nr 14 sprung, and for all that the middle decades of the 19th century saw in Vienna the rise of a prevailing style that became known as the "Second Rococo", a return to the flamboyance and ostentation of the late 18th century; one of central protagonists of the period being Peter Hubert Desvignes, whose redesign of Palais Liechtenstein stands as one of the central works of the period, and a project to which Michael Thonet's major contribution was laying parquet, and for which he employed his, patented, veneer bending process. Thus, in many regards, the formally reduced and reserved works Michael Thonet was developing and producing in his early years in Vienna represent a fundamentally contrary position to the prevailing fashion in the city. Or perhaps more accurately put, the curves, the florid, the ostentation are all there, can clearly be seen and understood: but are reduced down to lines, to a brief sketch of how a Rococo work may eventually look, albeit with a lot more formality and grace than the exaggerated faux of Rococo.

The obvious question is why Michael Thonet choose to go a different way?

Despite the wealth of tangible evidence in the Thonet (hi)story, the fact that the majority of the Thonet archives have been lost to war and political upheaval does mean there is still a lot of uncertainty and conjecture, including the answer(s) to such a question. Was it a fundamental opposition to the extravagance of the prevailing style, as would later be a contributing factor to the development of steel tube furniture? Was it a strong belief in a more reduced, honest formal aesthetic? Was it a desire to deliver more democratic, affordable, objects for Vienna's rapidly developing, and invariably poor, urban working class? Which role did Desvignes play, or indeed understandings of furniture in mid-19th century England? Which role did a benevolent, fiddle playing, dwarf play? Was it primarily a focus on developing a furniture application for his patent, regardless of formal aesthetic considerations? Is there a reason?

Whereby one must also remember Michael Thonet wasn't the only one working in Vienna with more reduced forms, at the same time manufacturers such as August Kitschelt were producing furniture from thin iron wire, furniture which although all logic tells you was for outdoors, was very much pitched for indoors, and furniture which formally is doing very similar things to the wooden works of Thonet; consequently, it isn't inconceivable that Michael Thonet was inspired by the iron furniture he saw, not least because the curves and meanders of both iron wire and bentwood not only allow for an implication of the extravagances of Rococo, in much more affordable objects, but also allow for a touch more stability.

That said, in terms of the formal aspects of Michael Thonet's bentwood chairs we do prefer our own grapevine theory, that the curves of wood are a reflection of freshly cut and lain vines, or perhaps young tendrils reaching out for a supporting wire around which to entwine: if we're all blindly asked to buy into the idea that Marcel Breuer was inspired for his steel tube furniture by bicycle handlebars, why shouldn't Michael Thonet have been inspired by a walk through a vineyard on a bright spring morning? Be that in the suburbs of Vienna or the steep slopes around Boppard, with the Rhein curving endlessly, naturally, honestly, calmly below him.

Michael Thonet died in 1871, after, according to the accepted legend, contracting a fever while inspecting a beech forest, and thus control of his company and legacy passed to his sons, a transfer that had been regulated in 1853 with the establishment of the company Gebrüder Thonet, Thonet Brothers; brothers who, unlike those of the Rheinland castles Sterrenberg and Liebenstein near Boppard didn't jealously fight over money, but cooperated to develop and evolve the family tradition.

An undertaking exemplified in Thonet & Design by works of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the high-backed Nr 17, the folding Nr 6310, the almost quadratic, almost occultist, Nr 51 or the Nr 141 desk chair, and thereby works which present varying understandings of form, function and materials, and also works which help approach an understanding of an interplay with the turn of the century Art Nouveauists: whereas the earlier 19th century works with their reduced, implied, florid curves could be considered as offering a template for the figurative floral motifs of the likes of a Charles Rennie Mackintosh, by the early 20th century it could be argued Thonet had learnt from Art Nouveauists, the influence of a Henry van de Velde being freely readable in a couple of the pieces, not least the Nr 511.

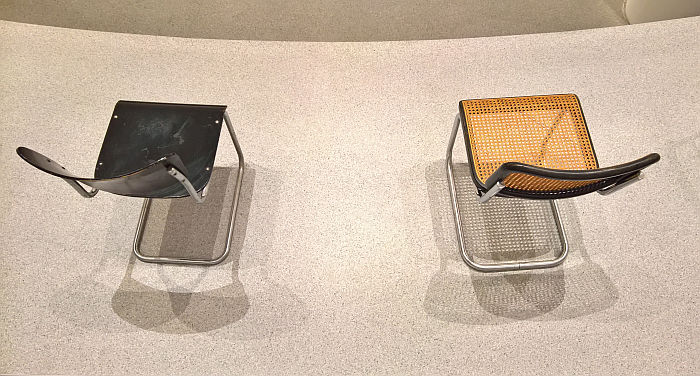

And works which flow in time into steel tubing, starting with two B 3 "Wassily" chairs by Marcel Breuer: one produced by Thonet Frankenberg and one by Standard Möbel Berlin. And thus perfectly underscoring that whereas the development of bentwood furniture is an achievement of Michael Thonet, steel tube furniture wasn't a Thonet development, Thonet being however very, very early adopters and one of the most important companies in the development and establishment of the genre. And that not just through the myriad works they produced in the inter-War years, but also formally. At least initially. And an influence neatly demonstrated in Thonet & Design by the close proximity, physically and formally, of Mies van der Rohe's MR 10 steel tube cantilever chair from 1927 and a 1904 B 9 bentwood armchair. Somewhat regrettably Thonet & Design doesn't feature any Thonet rocking chairs, the comparison to the MR 10 and, for example, the Nr 1 Rocking Chair being even more satisfying.

Featuring works predominately by Marcel Breuer such as the B 33, B 35 or B 55, but also a B 43 from Mart Stam and B 257 by Bruno Weill and André Guyot the steel tube presentation in Thonet & Design is brief, and thereby neatly reflective of the very short period in which steel tube furniture defined new understandings of a new society and new approaches to architecture, living and design; while the speed with which the presentation returns to wood confirming that despite the contemporary fascination with steel tube furniture, in the inter-War years wood was arguably more important. Something particularly well exemplified by the presence of the likes of Ferdinand Kramer's B 403, a work created in context of the Neues Frankfurt programme, or two inter-War works by Adolf Schneck realised in context of the Wiener Werkbund.

Despite the very determined, focussed and unwavering path Michael Thonet took, the (hi)story of Thonet, both man and company, is one inextricably linked to geo-political developments far outwith eithers control. When, for example, Michael Thonet was born, Boppard was French, only joining Prussia in the wake of the 1815 Vienna Congress, and thus just before Michael Thonet opened his first workshop. The same Congress transferring ownership of Johannisberg to Austria. Had it not, and had it not, Fürst Metternich would never have been resident in Johannisberg and couldn't have invited Michael Thonet to Vienna, where, and as previously discussed, he was greatly aided by his associations with the Imperial Court and the upper classes of Viennese society, before social and political evolution in the course of the 19th century saw that collapse and ultimately vanish with the First World War. As did much of the company's network and factories. The Second World War, and subsequent ideological division of Europe, almost, completing the job.

Post-war Thonet re-established itself in the ruins of their factory in the rural calm of Frankenberg, Germany, and also began to reposition itself formally, materially and conceptually, exploring new avenues, and that for all through cooperations with external designers. Among the post-War objects presented in Thonet & Design are works by the likes of Günther Eberle, Kurt Felkel, Gerd Lange, and a whole raft of works by Verner Panton, including very pleasingly a 270 F armchair a, for us, thoroughly contemporary object and inarguably one of Panton's more endearing chair designs. A further important step in Thonet's post-war development coming with the appointment in 2007 of the late James Irvine as Art Director, a tenure marked by cooperations with the likes of Konstantin Grcic, Naoto Fukusawa, Robert Stadler or Stefan Diez.

Thonet & Design, or at least the extant Thonet & Design part of the exhibition, ends with Sebastian Herkner's 118 from 2018; a work which, as previously noted, is essentially a re-imagining of the 1948 B 1, a work not on show, but a few levels below the 118 is the very similar B 3, also from 1948, and thus allowing for an easy comparison of the two and thereby delightfully underscoring what Sebastian Herkner achieved and how he reimagined the B 1/3, both from formal as well as technical/construction perspectives. And a comparison that involves a lot of stair climbing, thus helping keeping body and mind fit.

Presenting but a fraction of Die Neue Sammlung's bountiful Thonet collection Thonet & Design offers but the briefest of glimpses into the history of Thonet & Design, in many regards can do no more, so extensive is the Thonet canon, but does so in a very pleasing, probable and personable manner.

Amongst our highlights we'd list, and amongst others, a Siesta Medizinal recliner by Hans & Wassili Luckhardt, a work which, as noted in the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot's exhibition Anton Lorenz: From Avant-Garde to Industry, effectively kept Thonet afloat through the Second World War, and thus enabled the re-launch in Frankenberg, and a work which in addition paved the way for the heavily upholstered reclining armchair; a W 199 a by Walter Gropius and Benjamin C. Thompson from 1951, a work interesting for the various influences quoted within it, but for all because it was produced by Thonet Industries USA, and so back in the days before legal disputes and lawyers effectively banished the works on show in Munich from America; and, and arguably the highlight of Thonet & Design, one of the original, original, Nr 14s, and a chair produced from glued veneer strips rather than the bent solid wood in which guise it became famous, and which stands next to it, thereby allowing for a comparison of the two versions. And considerations on how important Michael Thonet's decision to try solid wood bending was for everything that follows in the exhibition. Had Michael Thonet not experimented with solid wood, and, most importantly, not been awarded a patent for that experimentation, it's arguable if there would be an exhibition such as Thonet & Design.

As we say, never underestimate a Thonet Nr 14.

And while we normally don't mention that which isn't on show in exhibitions, we feel mention must be made of the numerous X60 collections by Delphin Design, works which form the backbone of the company's contact work and thereby remind us that until the late 1860s Thonet sold exclusively in bulk, that the success of the Nr 14 was built on what would be termed to today contract/object business, and that that business remains the most important for the global furniture industry, as Michael Thonet foretold; and of the Thonet Slide realised in context of the Neue Sammlung's exhibition Friedrich von Borries. Politics of Design. Design of Politics, less a functional object as a comment by von Borries on how "Design Disciplines", the Nr 14 representing for von Borries an object whose regimented production method stands as representative of an enforced discipling of society enabled by design. And a work which once stood in the very space now hosting Thonet & Design. "We’re really looking forward to seeing how Die Neue Sammlung integrate it into their forthcoming Thonet exhibition", we opined backed in December, but sadly, presumably because it isn't a chair, they haven't.

What also isn't on show is female designers. The Thonet portfolio isn't exclusively male, we know and can confirm that. Thonet & Design is, or at least the named designers are, who is behind the anonymous in-house designs of decades past is, we'd imagine, neigh on impossible to determine. And that in such an exhibition, one tracing 200 years of chair design, no works by individual female designers are on display, tending for us to underscore the visibility problem of (recent) contemporary female designers, and the risk we noted in context of the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden's symposium A Woman's Work that "the narrative of early 21st century design is going to be recorded and perceived as being just as male as that of the early 20th century" It needn't be. If it is or isn't will largely be determined by manufacturers such as Thonet, museums such as Die Neue Sammlung and exhibitions such as Thonet & Design

Unequivocal as the exhibition title may be, Thonet & Design is, and as we hope the above makes clear, Thonet & Chair Design, something underscored by the absence of the very first Thonet product acquired by the Neue Sammlung, a B 9 stool by Marcel Breuer; and a not unimportant difference as understanding Thonet, understanding Thonet & Design, requires, demands, understanding the full breadth of their output. However given the central importance of chairs in the development and evolution of Thonet they represent a most appropriate filter through which to explore the (hi)story, evolution and development of the company, while through blocking out all other distractions and contexts, Thonet & Design does allow for a very concentrated, satisfying and absorbing tour through the history of Thonet's chair designs and thereby of Thonet's contribution to the development of contemporary chair design in its myriad technical, aesthetic and commercial facets.

Albeit if while wandering through and enjoying the presentation we were accompanied by the peel of alarm bells: an exhibition about the development of chair design based on works by one manufacturer in a presentation in which the same manufacturer is a cooperation partner. And an exhibition which not only opened in the week said manufacturer launched a major sales exercise based around their 200th anniversary, but an exhibition to whose preview the PR agency retained by said manufacturer undertook a major mobilisation.

In such moments, and they do occur with an irregular regularity, we always refer to the "Thonet Test" we developed in context of the 2014 exhibition Sitting – Lying – Swinging. Furniture from Thonet at the Grassimuseum Leipzig, an exhibition which similarly explored the development of chair design as exemplified by the works of one Frankenberg based manufacturer; admittedly a poorly defined test but one which, in essence, asks in how far commercial interests have defined the museal presentation. Does it look and feel like a trade fair stand?

A test Thonet & Design passes. Not least because, and as can be understood through the presentation, Thonet are so central to the development of furniture design and the furniture industry, its impossible to discuss such without mentioning Thonet, and a reality that places them, in many regards, outside such considerations; Thonet exist as much as a cultural good and as a commercial concern, Thonet, the (hi)story of Thonet, the products of the (hi)story of Thonet, should, must, be exhibited in museums, important is that the presentation, as in Thonet & Design doesn't entice purchase through a suggestive, emotional, presentation which makes unqualified, unacademic inference or which places an unnatural, improbable focus on commercially available models, but which remains throughout its flow a sober, reflective review which includes those currently commercially available works, but set firmly in a wider context.

And yes we are very much aware that posts such as this are part of such an exhibition.

And while arguably it would have been preferable had Thonet not been involved, had everything been arranged without having Thonet as cooperation partner, a large part of Thonet's involvement isn't commercially available, or at least not yet.

Looking back is but a component piece of looking forward, or put another way, viewing Thonet & Design an unavoidable, recurring, question is/was, what will be on the podiums by way of celebrating Thonet's 300th birthday? We would hope testimony to Thonet's role in the development of a new, as yet undefined, chapter in the history of furniture design, for while Thonet have a lot, more than most, to be proud of, in order that that past remains relevant they must keep moving towards the future. Which yes, is an opinion we've been vocalising for quite a few years now......

.....................and pleasingly Thonet & Design also presents an indication of movement in the form of prototypes of the so-called DNS chair and stool by Atelier Steffen Kehrle, ASK, a project developed for Die Neue Sammlung in conjunction with Thonet, and a project very much still in progress. Formally the DNS chair and stool do nothing particularly new, which isn't a criticism, far less an accusation, and as an object has its visual and conceptual appeal, based as they are on the development of a position and theory, specifically considerations on contemporary/future requirements of seating. 'twas but prototypes, so we can't comment on the sitting comfort. But more important is what isn't on show, or put another way, the fact that, and as ASK state, material and production process are still to be confirmed.

And that is where the future is.

As technological realities evolve and develop designers receive new tools, new materials, new opportunities to respond to evolving and developing cultural, social, economic and environmental realities; it's not just how we sit that's important, it's how that on which we sit is produced, from what is produced, why its produced, when it is produced, where it is produced, and increasingly by whom: modern technology allowing for both self-make open design but also increasing decentralised commercial production. And it is this focus on materials and processes which defines the Thonet bentwood and tubular steel furniture, the forms aren't irrelevant, are arguably important in that they reflect a response to prevailing conditions and embody a break with conventional understandings and promote a new formal vocabulary. But the forms aren't decisive. The materials, process and for all the combination and interplay of materials and process are. With the bentwood, the sales and distribution process and channels are equally intimately linked with materials and process. Post-war, and generalising to point of falsehood, the focus as represented by the works on show in Thonet & Design is much more on the formal and functional aspects, and/or about an authorship on the part of the designer: the material being chosen because it allows the creation of the desired form/function. Accepting therein the inevitable generalisations we're making and exceptions we're ignoring.

And so if in the next stages of the development of the DNS collection Thonet give ASK the freedom to challenge accepted material and production conventions, to explore what nascent, developing, technology and materials can achieve, also in terms of distribution, the end result could be very interesting. We assume, we'll all be the wiser at Orgatec 2020.

And perhaps, who can tell, by way of an omen, and as testified to by the models and prototypes on show, the cantilevered DNS began life as a four legged chair, much like Marcel Breuer's steel tube cantilevers.....

Based around an exhibition design concept conceived by ASK, Thonet & Design takes the visitor on a chronological journey from the Boppard Chair to the 118, the Offenbach Chair as we, alone, know it; a journey which although temporally straight, physically meanders and weaves every bit as playfully as the Rhein. And that most pleasingly, not least because the inherent gradient of the room, as with that at the Bopparder Hamm, allows for a literal overview of the (hi)story of Thonet chair design, including the chance to view chairs from above, a rare, and not uninteresting perspective. The equally important rear view being in contrast regrettably obscured by the grey diving walls; reminiscent of Rhineland vineyard terraces they may be, but one can't help thinking transparent barriers would have been more instructive, and, if we had a complaint, that would be it.

And if we did have a second complaint, sorry, it would be the lack of examples of Thonet chairs to try: the design of a chair not being the form alone but also being, and amongst other factors, the sitting comfort, functionality and tactility. Yes that would add to the feeling of a sales pitch, but would, for us be an important extension, simply because chairs are made for sitting on, are designed for sitting on. Not for looking at.

And if we did a third complaint it would be that the visitor is largely left to interpret on their own; that much like a tourist viewing the castles and vineyards passing by from the deck of a Mittelrhein cruise ship, there is no information to help guide you through the nuances of what you are seeing, to explain the passage that is unfolding before your eyes. You're enjoying it, it's accessible, it's nicely paced, it's entertaining, satisfying, engaging and you're glad you're there, glad you're aboard, you're learning and you'll definitely take something home from the experience, and plan to research further yourself. But if you don't have a guide or a guide book, you're going to miss some of the best bits. Guides and guide books are available in the form of guided tours and the accompanying catalogue. But a few brief texts would also be helpful.

The exhibition space hosting Thonet & Design was previously home to a permanent presentation of the Neue Sammlung's bentwood furniture collection, and thus the space's conversion to an exhibition of Thonet chairs is most appropriate; allowing as it does for an expanded and extended exploration of the canon of the main protagonist of the development of bentwood furniture and thus, and in contrast to most all other Rheinland tales, explains what happens next, how the central character learned from, developed, extended and disseminated that which occurred Once Upon a Time in Boppard am Rhein........

Thonet & Design runs at Die Neue Sammlung, Pinakothek der Moderne, Barer Straße 40, 80333 Munich until Sunday February 2nd 2020.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://dnstdm.de