Today industrially produced objects are so self-evident and ubiquitous it can be hard to believe there was a time when they weren't.

There was.

With the exhibition Unique Piece or Mass Product? the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge Berlin explores the developments of industrial production in the early 20th century, the discussions and discourses which accompanied those developments and the connections between such developments and the evolution of both formal understandings and the role and function of designers.

The second in the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge's 111/99. Questioning the Modernist Design Vocabulary series of exhibitions which in the course of 2019 will seek to explore the inter-relations between the Deutsche Werkbund and Bauhaus in the development and dissemination of modernist ideals, Unique Piece or Mass Product? begins, in many regards, certainly philosophically, long before 1919 and the establishing of Bauhaus, long before 1907 and the establishing of the Werkbund, and in the discussions concerning domestic objects which developed in the course of the late 19th century, for all in a popular position amongst European reformist factions that exposure to well made, meaningful, beautiful objects would improve the social fabric, that well made, meaningful, beautiful objects would, if you will, transpose themselves onto the users and help create a well made, meaningful, beautiful society.

Positions that arose from the evolving political and economic realities of Europe at the period; positions which encapsulated a longing amongst certain sections of European society to break away from the confusions and excesses of the stylistic forms of the period, forms which far from being considered well made, meaningful, beautiful were understood as historical and fraudulent in a brave new age of science and emancipation; and positions which were initially (largely) expressed through a move towards the, perceived, honesty and simplicity of traditional crafts. Invariably in association with nature.

However as the 19th century ceded to the 20th the need to supply an ever burgeoning urban population with ever more, affordable, goods necessitated an increasing shift to industrial, machine, production; and while machine production doesn't automatically preclude traditional, vernacular forms, indeed much of the early machine made goods were machined reproductions of traditionally handcrafted forms, those who advocated a greater use of machine production understood the two as being inextricably linked, argued that we needed new forms for a new machine age, new forms which better reflected contemporary society ..... but, and much like a "Brexit", what does that mean? And how does one achieve such?

As Unique Piece or Mass Product? explains there was (more or less) some general agreement amongst the protagonists of the period: ornamentation was widely understood as not only superfluous but undesirable; it was agreed that objects should be so formed so as to not only serve their purpose but clearly indicate what that purpose is; objects should be reflective of their materials, should employ the properties of a material rather than being forced to conform to them. Beauty, so the argument, arising from the inherent integrity of such forms. The deeper debate was how they could, should, be best achieved, and for all how much authority, prominence, responsibility should be given to machines? And how much should the artist, the craftsperson, retain?

Amongst the more central debates in the early years of the 20th century, and a debate which lies at the very heart of the question "Unique Piece or Mass Product?" is/was the so-called Typisierung Debate: a debate which developed within the Deutsche Werkbund in context of the discourse on how best to harness and utilise the possibilities afforded by developing industrialisation in order to improve the quality of the German goods of the period, which was the central function of the Deutsche Werkbund in its early years, for lest we forget, and as oft noted in these dispatches, at the turn of the 19th/20th century "Made in Germany" was more a form of derision than guarantee of quality; a debate which reached its public highpoint at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition Cologne, pitching those, led by Hermann Muthesius, who favoured the development of standardised, machine orientated, objects against those, including Henry van de Velde and Walter Gropius, who defended the creative freedom of the individual artist, a freedom which doesn't exclude machine production, but which starts from the artist not the machine.

And a debate that can be followed from the Deutsche Werkbund into and through Bauhaus: whereas, and at the risk of simplifying to the point of inaccuracy, the Weimar Bauhaus was initially about artistic freedom and craft, by Dessau it was increasingly about standardised machine production. A shift that symbolises an evolution in Gropius's own understandings in the course of the early 1920s, a shift that helps explain the (apparent) contradictions between Bauhaus Weimar and Bauhaus Dessau, and why not all Weimar Bauhäusler moved with the institution to Dessau, and a shift that was expressed more generally throughout the 1920s as progressive artists moved ever more towards the standardised, mass produced, object as the primary solution to the challenges of the period, and thereby one of the defining popular understandings of inter-War architecture and design.

And a standardisation which Unique Piece or Mass Product? neatly, and importantly, demonstrates wasn't the starting point of the period, but a reality which developed in the course of it through an ongoing discourse within creative and industrial circles, such as the Deutsche Werkbund and Bauhaus.

The nature of the discourse that accompanied the advance of standardised mass production throughout the first decades of the 20th century is explained in Unique Piece or Mass Product? through concise, informative, bilingual German/English texts, but for all through quotes from practitioners of the period, both the well known protagonists and also those whose voices are less often heard, including, and amongst many others, Josef Frank, Hugo Häring or Mia Seeger; and an intelligent and pleasing decision as the quotes allow for a more immediate, unfiltered, understanding of the various arguments and positions.

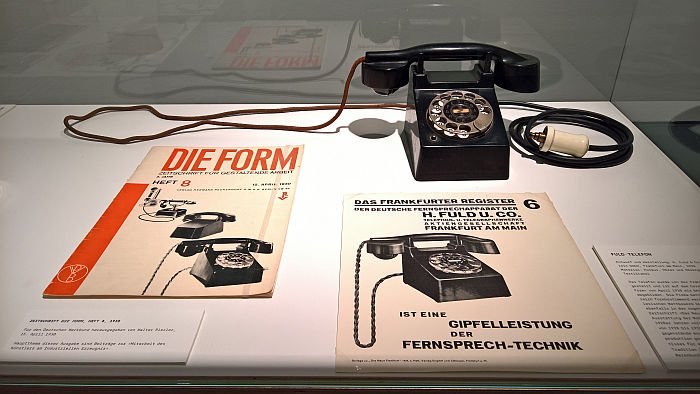

Arguments and positions which are backed up by a bijou selection of objects which embody the various moments in the debates, including a 1926 tea glass by Josef Albers which reflects the Bauhaus hang to geometric forms; laboratory beakers from Schott & Gen. Jena which underscore that technical/industrial goods can be designed according to the same principles as domestic goods; the Frankfurter Fuld telephone as a technical rather than artistic object; and two lamps by Wilhelm Wagenfeld: the W1 "Bauhaus Lamp" from 1924 and the WV 343 for Lindner from 1955. Two lamps separated by not only 30 years, but by a fundamental shift in Wagenfeld's understanding of form and forming, a shift which although going far outwith the principle timeline of Unique Piece or Mass Product?, one could argue is reflective of a shift that occurred throughout the timeline of Unique Piece or Mass Product? as designers began to better understand, and for all began to be able to better reflect on, machine production, and began to increasingly find their own creative voices in industrial production.

Or put another way, whereas at the start of the 20th century those developing industrial products were largely not only artists in name but by training, and thus initially dealt as such, we all remember, for example, from Peter Behrens. The Practical and the Ideal at The Kaiser Wilhelm Museum Krefeld that Behrens' first steps as an industrial designer were faltering ones as he struggled to comprehend the limitations of machine production, that one couldn't simply transfer a 2D form into 3; in the course of the 1910s and 1920s not only did Behrens and his contemporaries learn to grasp the differences between art and industry, but there arose, thanks to schools such as Bauhaus, a new generation who were trained specifically to create objects for industry, individuals whose principle focus was the realisation of the practical rather than the decorative, of functional objects designed specifically to be machine produced rather than artistic objects which could be produced by machines. And thereby a shift which not only saw the origins of the industrial designer as a distinct profession far removed from the artist, but which led to new understandings of form being related as much to the means of production as to considerations on function or aesthetics.

Much as Commercial Design instead of Applied Art?, the first exhbition in the Werkbundarchiv's 111/99 series made reference to historic exhibitions, so to Unique Piece or Mass Product?; interwoven through the narrative are considerations on three exhibitions which stand as exemplary for the discussions of the period, and which also presented the objects presented in Unique Piece or Mass Product? to illustrate their positions: starting with the 1923 Bauhaus Weimar exhibition, an exhibition which Gropius opened with his speech "Art and technology, a new unity", thus defining the shift in thinking at the school; the 1924 Stuttgarter Werkbund's exhibition Die Form, an exhibition perhaps best summed up through the catalogue's title "Die Form ohne Ornament" [The Form without Decoration]; and ending with the MoMA New York's 1934 Machine Art, the institution's inaugural design exhibition and one which, according to the MoMA demonstrated, “a victory in the long war between the craft and the machine."1

A somewhat premature, and unnecessarily euphoric, claim we'd argue; and certainly not an end to the question, Unique Piece or Mass Product?

On the one hand the debate continued post-War, perhaps most fervently in the Land of Bauhaus, through the so-called Formalism Debate of 1950s East Germany; the positioning of the argument may have been different from that half a decade earlier but in essence, one can argue, the preference given by the DDR regime for heavy hand-crafted furniture over lighter, standardised objects being based on a belief that the worker needed the Unique Piece, and the shift which followed in the course of the 1950s to the Mass Product, and as discussed in Shaping everyday life! Bauhaus modernism in the GDR @ the Dokumentationszentrum Alltagskultur der DDR Eisenhüttenstadt was similar to that in the course of the 1920s. If not accompanied by a debate. Or at least not an open democratic one. Similarly post-War Denmark where, and again at the risk of generalising to the point of untruth, while a Hans J Wegner insisted his chairs should be made by Danish craftsmen, a Børge Mogensen was much more in favour of machine production. It's not a 1:1 repetition of the debate of the 1910s and 1920s, but it's the same question, Unique Piece or Mass Product?

But for all, whereas the standardised machine production developed in the inter-War years may have allowed for the mass supply of goods, for the mass supply of well made, meaningful and affordable goods, it didn't, cannot, satisfy the very individual demands we all place on those objects with which we chose to surround ourselves, for all our formal and aesthetic demands. A disparity that, arguably, through the inexorable rise of our consumer culture since the 1950s has become ever more acute. Consumers want the Unique Piece. Industry and commerce the Mass Product.

?

Squaring that particular circle may however not be that far away: an Industry 4.0, with its increased use of 3D printing and similar rapid technologies, coupled to the swathes of new materials currently being developed, will allow for, or perhaps more accurately put, should, must?, allow for, the mass production of unique pieces. A genuine new unity of art and technology.

And a state of affairs which will not only see a further evolution in the role of the designer, moving the designer even further away from the artist and positioning them ever more as a technical service provider, but will increasingly involve the consumer directly and actively in formal aesthetic decisions, in decisions of the meaningful and beautiful, and thereby increasingly pose ever more fundamental questions on the nature of consumption, and ultimately the role, necessity, of industry.

Or put another way, today industrially produced objects are so self-evident and ubiquitous it can be hard to believe there will come a time when they aren't.

A compact yet expansive and informative exhibition, one which relies to the greater part on texts rather than objects, including examples of the three historic exhibition catalogues and related, contemporary, magazines for visitors perusal, Unique Piece or Mass Product? isn't an exhibition that can be unthinkingly viewed but rather demands the active cognitive participation of the visitor, something of which we very much approve; but is for all an exhibition which allows one to approach a more realistic understanding of how industrial production developed in the course of the 20th century, how the role of designers in product design evolved, and thus for a more differentiated perspective on the importance and relevance of the early 20th century for early 21st century product design.

Unique Piece or Mass Product? runs at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Oranienstraße 25, 10999 Berlin until Monday August 19th

1"Machine Art" in The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 1, No. 3, November 1933

Full details can be found at www.museumderdinge.org