"Sometimes one has to remind oneself that this change took place in one generation - such is the gap between the woman of today and of yesterday, between the girl of then and of now."

So begins the German magazine Die Woche's 1930 article "Mädchen wollen etwas lernen", "Girls want to learn something", an article which opens Four "Bauhausmädels" and is subsequently extend by the Angermuseum Erfurt to explore not only what Gertrud Arndt, Margarete Heymann, Margaretha Reichardt and Marianne Brandt learned at Bauhaus, but how they subsequently applied that "something".

Preparing for our visit to Erfurt it's probably fair to say we spent most of our time reflecting on the exhibition title. Or better put, the "Bauhausmädels" - Bauhaus Gals - part. We didn't/don't have any issues with the "Four". But "Bauhausmädels"?

Our initial reaction was that we didn't like it.

Yes, the Angermuseum noted it was a contemporary phrase of the period, that then, as now, "Bauhaus" could/can be used in all manner of contexts as a "cipher representative of the contemporary modernity of the time": Bauhaus Chair, Bauhaus Lamp, Bauhaus Architecture, Bauhaus Gal. And therefore the Bauhaus in "Bauhausmädels" underscores a level of emancipation that was not only new but defined by an innate sense of legitimacy and self-confidence, and which was going to take society in new directions. And a new generation of young women whose primary ambition in life wasn't to become "Heiratsfähig", suitable for marriage.

And we get that, but.....

.....on the one hand "Mädel" can, in the wrong hands, all to easily become "babe", "doll", "honey" which is, we'd all agree, less respectful, less progressive, and on the other given the fact that females didn't enjoy full, unreserved parity, not just at Bauhaus but in the wider 1920s, is it appropriate to use "Mädel" in an exhibition title about female Bauhaus students....? Or does it tend to trivialise, and thereby reinforce the disadvantages females of the school, and day, faced?

But then, we're all in favour of expressing historic realities with all their warts, believing as we do that such allows for a more honest, open and meaningful discussion. If you start a discussion on historic events by deliberately ignoring phrases, terminology, words because they offend our contemporary sensibilities, what can we learn? And museums exist so that we can all "etwas lernen"

Unsure, uncertain, unable, we decided to wait, to view the exhibition and then consider the title in context of that which is presented......

Despite the fact that not only in name but in content Four "Bauhausmädels" is about Gertrud Arndt, Margarete Heymann, Margaretha Reichardt and Marianne Brandt, one is greeted in the Angermuseum not by the four, but by a wall of female faces and a collection of photos of other female Bauhäusler, such as, and amongst many others, Karla Grosch, Lieselotte Boehme, Ida Thal or Katt Both; and thereby an introduction which makes clear that the four protagonists stand representative, proxy, for the wider female Bauhäusler.

Not that Four "Bauhausmädels" should be understood as staging a direct confrontation with the realities of life as a female Bauhaus student. It's not. Not that it ignores the subject. It doesn't, it is referred to, perhaps most satisfyingly through a large format quote from Walter Gropius noting that "For the time being, women can no longer be accepted into the ceramics workshop. Women's department or bookbinding", the "women's department", Frauenabteilung, being the weaving workshop. But such attitudes, such patronising, isn't the direct focus of the exhibition, rather as an exhibition the focus of Four "Bauhausmädels" is much less on the trials and tribulations experienced by the four and much more how they used the possibilities, the freedoms and liberties Bauhaus did allow them, and how they subsequently took the experience of utilising that freedom out of the (relatively) protected space of Bauhaus and found their feet and their own creative voices in inter-War Germany.

To this end the focus of Four "Bauhausmädels" is very much the creative output of the quartet; biographical information is kept to a minimum, it's all about the work, about better understanding the artist through their work, rather than understanding the work through the artist.

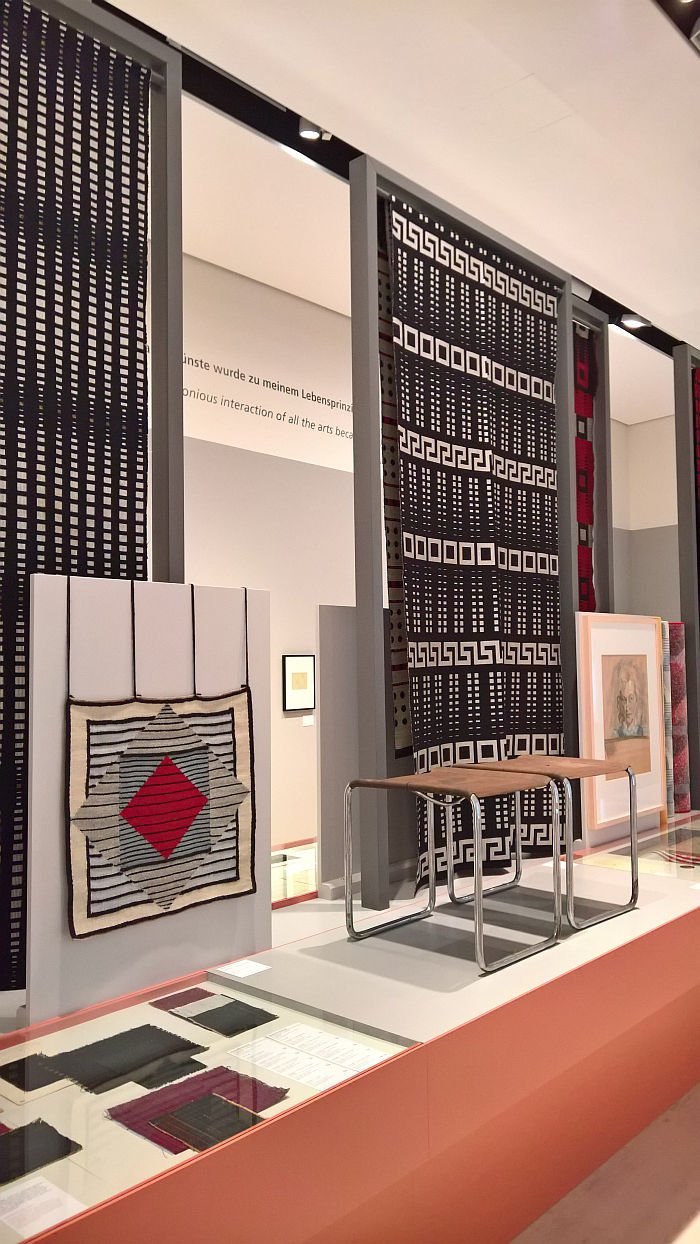

And a focus which sees each of the four given their own space in which examples of their Bauhaus and post-Bauhaus creativity is presented; a presentation which by necessity of the nature of many of the objects is very much of the small objects behind glass type, which, as we all know, is never an optimal solution. If one that in Four "Bauhausmädels" is given a dynamism and movement through a combination of the orientation of the vitrines and the exhibition colour scheme, but for all through the fact each of the four protagonists stands representative of a different craft, a different component of the Bauhaus programme, not exclusively, each is represented by works in a range of genres, but the concentrated "one-designer-one-discipline" format allows for a very neatly overlapping generic journey through Bauhaus photography, metalwork, ceramics and women's work weaving. The latter being represented through Margaretha Reichardt, and a presentation which in addition to presenting decorative works also includes more technical works, for all Reichardt's experimentation with and development of Eisengarn, a cotton thread fortified with starch, wax and paraffin oil but not with iron, it merely resembles iron, and a material that was used to cover Bauhaus furniture objects, including, and as presented in the exhibition, Marcel Breuer's B4 folding chair and B9T stools, thereby demonstrating that at Bauhaus experimentation did occasionally became practice. And that women's work could be research.

The weaving workshop was also the principle academic focus of Gertrud Arndt's time at Bauhaus Weimar, if not a particularly fulfilling one; or as Arndt put it, "I never wanted to weave... All these threads, I didn't like that at all". Arndt, who had enrolled at Bauhaus Weimar with the intention of joining the non-existent architecture department, later found a more fulfilling output for her creativity in photography and Four "Bauhausmädels" presents numerous examples of her work, with a principle focus on her series of "Masked" self-portraits from the late 1920s, self-portraits which although taken in Dessau weren't taken in a (direct) Bauhaus context, even if their experimental and questioning position could be considered of Bauhaus.

Margarete Heymann is represented by and representative of ceramics, for all that which she created in context of her own company, Haël-Werkstätten für Künstlerische Keramik in Marwitz near Berlin, and which she ran from 1923 until 1934 when on account of her Jewish ancestry she was forced to relinquish it, or as an article in the Nazi newspaper "Der Angriff" would have us believe, until 1934 when being of Jewish ancestry she simply abandoned the factory and her staff to the rats and bats of Brandenburg, until, mercifully, a German came along and rescued all from the Schreckenskammer - Chamber of Horrors - the Jew had left behind. As we're noting a lot these days, fake news ain't a recent development, its' just adapting to new realities. And we all need to be very, very careful.

The largest section, at least in terms space is given over to Marianne Brandt, to the metal workshop and therefore a domain that in the original Bauhaus plan was not one to which women were to be admitted, a plan which László Moholy-Nagy choose to ignore in inviting Brandt to join him, and an invitation Brandt instinctively understood how to use, "Moholy-Nagy ... gave me mettle for metal. That's all", she pronounces. Which is not only the most deeply satisfying translation of the original German "Mut für Metall", but also helps better explain the spirit in which Brandt's mettle works were realised. In Four "Bauhausmädels" the principle focus is her work with and for the Gotha based manufacturer Ruppelwerk whom she served as Head of Design from 1929 to 1932; a cooperation which, as we've noted before, was fulsome, and which Four "Bauhausmädels" explains was even more fulsome. In addition to the familiar napkin holders, bookends, matchbox stands, et al the exhibition also presents, and amongst other genuinely charming Ruppelwerk objects, a so-called Savings Calender in which one can only access the calender by adding a coin to the associated savings box, and which wouldn't look out of place in an Braun catalogue; a delightful double candle holder whose form is very similar to a ceramic one by Margarete Heymann, and thus implies a translation of ceramic into metal, if not directly Heymann's; and a lamp which differs significantly enough from Brandt's work for Kandem Leipzig to allow on to understand that she was, we'd argue, adept at adapting her design to the technical possibilities and specialities of the client. Which is, we'd, again, argue, the kind of designer you want to work with.

Equally as instructive and engaging as the works realised by Marianne Brandt are the works not realised by Marianne Brandt: Four "Bauhausmädels" presenting a series of product sketches from the early 1950s, a series of product sketches from her time, first working alongside Mart Stam at the Staatliche Hochschule für Werkkunst Dresden, and subsequently with the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung at the Kunsthochschule Berlin Weißensee, and sketches which give the impression of a creative hoping to re-start a career the war years had disrupted. Hopes, as history records, the so-called Formalism Debate in the DDR scuppered. And means today we can only enjoy her post-War designs, including a very interesting looking lamp design, as sketches.

Which is disappointing.

As is the general way Four "Bauhausmädels" tells only very little of the fours' post-War activities. Yes, such would require space the Angermuseum simply doesn't have, but given the wider narrative of emancipated females grasping the new possibilities presented by new understandings of social relations, the extended, post-War, biographies are, we'd argue, important: that Gertrud Arndt turned away from a creative path, that Margaretha Reichardt enjoyed a long career in the DDR that Marianne Brandt didn't, Margarete Heymann's mixed fortunes in England, all completing narratives begun in a spirit of youthful zeal in Thüringen.The lack of such a discussion doesn't detract from the presentation, but it's absence is very present, one can almost hear it knocking at the door, begging to be let in.

But outside it remains. Hopefully it will be invited in at a later date for a future series of exhibitions.

However, as we say, the absence doesn't detract from the presentation and as an exhibition Four "Bauhausmädels" provides not only for a clear, concise and entertaining introduction to, and better understanding of, the creative output of its four protagonists, of the developing understandings of form in the 1920s, how the utilisation of new materials and processes aided and abetted such formal evolutions, how the four contributed to such formal evolutions, but also allows for a better understanding of the trials and tribulations experienced by the four, even if that isn't a primary focus.

And the title?

Yes, the exhibition presents four female creatives who in their own way challenged the accepted understandings of the day; Reichardt through her experimentation, Brandt through her position at Ruppelwerk, Heymann through establishing and leading her own company, Arndt through her resistance to the Frauenabteilung and moving to photography, and as such Four "Bauhausmädels" can be understood as four females holding up a middle finger to a waning but still dominant patriarchal supremacy, or as Die Woche put it "woman no longer want to be dependent ... They head out into the world ..... unselfconscious and assuredly they mix with male students, just as later in life they will have to work side by side with them"

But then, at the end of the article, the tenor changes a little, "today we know a type of the learning girl who does not neglect the freshness and delicacy of the feminine, but rather fosters it with a special touch" it informs us, and continuing into the final sentence "Perhaps these matters of taste and dexterity, of theatre and dance are better suited to the feminine psyche than others"

And thus as an article reminds us of the language the late 19th/early 20th Swedish author Ellen Key uses in her 1913 essay Beauty in the Home*: progressive, reformist, enlightened, but unable to fully move away from the conventions of the past, unable to fully emancipate itself from the gender roles and gender conventions of the past.

Which, inescapably, brings us back to Bauhaus.

"We are fundamentally against the training of female architects" wrote Gropius in 1921. Women were welcome in Weimar as long as they wove, pottered or bound books. Because that is what women can do, arguably what they want to do, where they can best express the "freshness and delicacy of the feminine."

At Bauhaus women were both empowered but were also limited in how far they themselves could determine that empowerment, may not have wanted to be dependent, but weren't fully independent, as Mädels at Bauhaus they were in unison Mädels in the augmentative and Mädels in the diminutive.

And thus its use in the title allows for reflection on the disparity between the world the four were helping create and the one in which they existed. And by extrapolation for their role in an evolution that was, arguably still is, progressing.

And which thus all the better underscores the scale, relevance, importance of that which Gertrud Arndt, Margarete Heymann, Margaretha Reichardt and Marianne Brandt achieved upon leaving Bauhaus, something which a generation before, before not only Bauhaus but all the other education institutes slowly advancing more progressive, reformist agendas, would have been unimaginable. But to which Bauhaus could have been more supportive.

And which, for example, the title "Four Bauhäsuslerin" wouldn't have been able to transmit.

And so one can thus accept its use. Uncomfortable, disconcerting and downright awful a phrase as it may be.

Four "Bauhausmädels" runs the Angermuseum, Anger 18, 99084 Erfurt until Sunday June 16th

* Beauty in the Home was first published in 1899, the version we have is a translation based on a 1913 version

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://kunstmuseen.erfurt.de