When one considers the, let's say, unique, derisive, unalluring place the Sächsisch dialect enjoys endures amongst German speakers, it could be considered unwise, foolhardy, to explore all too deeply the contributions made by creatives and industry in and from the State of Sachsen to the development of Bauhaus, to explore, if you will, Bauhaus's Sächsisch accent.

With the exhibition Bauhaus_Sachsen the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig do just that.......

In order to avoid any misconceptions, and for the benefit of all unfamiliar with the finer points of regional, vernacular, German; the smow blog isn't from Sachsen, was however based for many years in Sachsen, many very happy years, and we still return regularly and happily to Sachsen. But there is no getting away from the fact that amongst the myriad German regional dialects, that spoken in Sachsen is not the most admired, envied, beloved. Amongst the people of Sachsen yes, in Sachsen it's a badge of honour all wear proudly and prominently; but is less loved elsewhere. Indeed, in a 2008 survey the public opinion researchers at the Allensbach Institut recorded that 54% of Germans didn't like the Sächsisch dialect, making it the most unpopular by a country mile.1

And so hardly the chosen language of innovators, artists and poets. Yet it was once was. Luther, for example, reformed the church in Sächsisch2, while in his 1672 work Der Teutschen Sprache Grundrichtigkeit und Zierlichkeit [The German Language, Accuracy and Finesse], the theologian and philologist Christian Pudor advises readers, in context of the question how one can best learn to use fine language, to visit the contemporary Sachsen, where "The Meißner stand before all others on account of their delicate dialect, hence their words, because they are pure and unambiguous, can be confidently employed."3 Meißen being not only a seat of power in region at that time, but where in first decade of the 18th century Augustus the Strong held the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger captive in the Albrechtsburg until he had successfully manufactured gold. Which he, oddly, never did. What he did however was to develop in 1708 a process for making porcelain, thus launching the European porcelain industry and establishing Meißen, Sachsen, as a by-word for not only quality and innovation but as one of leading definers of good, contemporary, taste and form throughout Europe. And is there not something irrefutably Modern in the reduced geometry of Meißen's crossed blue swords?

And that, original, understanding of Sächsisch as reformist, pure and unambiguous, that which one can confidently employ and which through its innovation advances society, technically, artistically and culturally, is the Sachsen explored in Bauhaus_Sachsen.

Thus, and having elegantly extracted ourselves out of the hole we'd unnecessarily dug.....

As with any school Bauhaus is nothing more than the sum of its staff, pupils and the works they produced, both at the school and later in their careers. Being anything but any school a Bauhaus school is/was also, for all in its Dessau incarnation, about the design of contemporary goods for contemporary industry, and thus about the partners it entertained and the works thereby realised by its staff and students.

And these works are very much the focus of Bauhaus_Sachsen, the story of the school itself is largely ignored as is any discussion of formal, functional or pedagogical aspects/developments; and although one could, therefore, potentially consider it to be more an Art_Sachsen exhibition or a Design_Sachsen exhibition, the context is very firmly of a creativity nurtured, explored and enacted within and directly informed by Bauhaus.

It is very much a Bauhaus exhibition, one told through both the works realised by students and staff from Sachsen, and the works realised by staff and students in Sachsen, and one which in doing so underscores the contribution(s) made by Sachsen to Bauhaus and the inextricable connections between Bauhaus and Sachsen, or perhaps better put Bauhaus_Sachsen.

To this end Bauhaus_Sachsen weaves several discourses through its presentation, that, arguably, most directly linked to Bauhaus_Sachsen being works created by Sächsisch Bauhäusler, those of native Sächsisch tongue, many of whom, and in a move one imagines was specifically designed to annoy Goethe, were employed in the Bauhaus scenography/stage workshop, including Lothar Schreyer, the first head of workshop, Kurt Schmidt or Erich Mende, who welcomes visitors to the exhibition through a recreation of a stage set figure he designed in 1930.

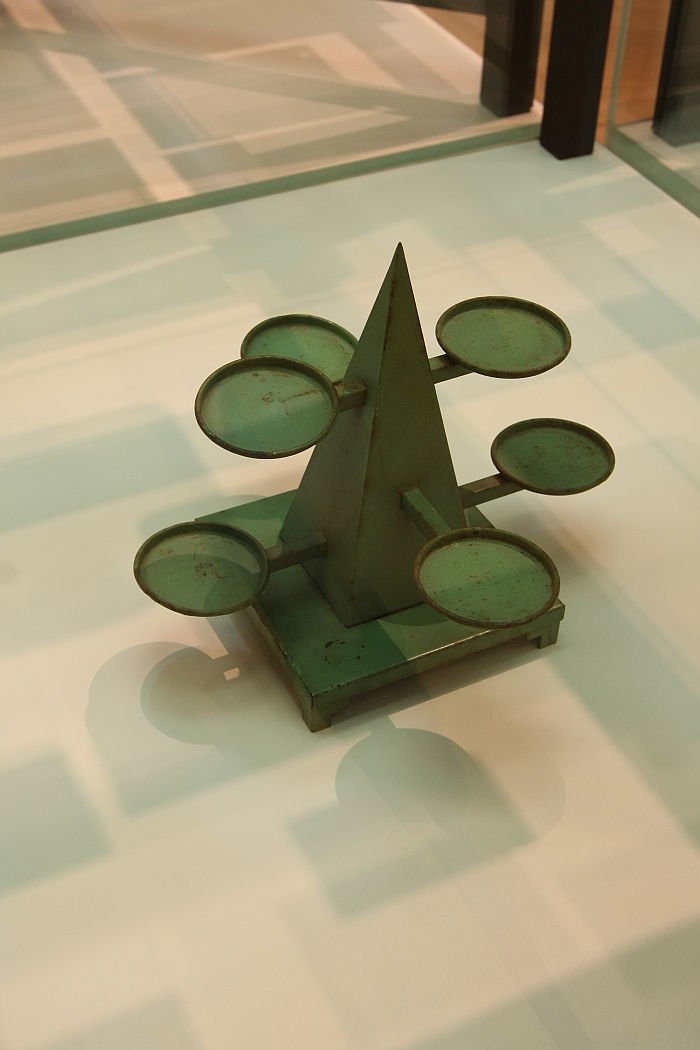

Elsewhere Bauhaus_Sachsen presents Sächsisch Bauhäusler as varied as, and amongst many, many others, Franz Ehrlich, Albert Hennig, Hermann Trinkaus and Marianne Brandt, a creative who, and somewhat inevitably is granted her own section. Not that we're complaining, far from it, we delight in every opportunity to deepen our understanding of Marianne Brandt and her work; work which in Bauhaus_Sachsen is represented in both 2D and 3D forms, the latter including examples of her work for the Ruppelwerk Gotha for whom Brandt served between 1930 and 1932 as Head of the Design Department, not only repositioning and refocussing the visual aesthetics and functional perspectives of the company, but realising innumerable objects, including, and one of our genuine highlights at Bauhaus_Sachsen, and a new Brandt work for us.... a cactus stand. It's quite low down in a glass vitrine, you could easily miss it, certainly misinterpret it, we thought it was a tea-light holder, so, a Christmas deco tea-light holder type thing. No, it's a cactus stand. Who knew such was needed. In 1932 or 2019? An absolute joy.

Marianne Brandt's work with Ruppelwerk came after she had left Bauhaus, yet while at Bauhaus she was also one of the school's most prodigious, working, designers, for all in her cooperations with Leipzig based KANDEM

Established in Leipzig's Inselstrasse in 1898 by Messrs Max Körting and Wilhelm Mathiesen, Körting & Mathiesen a.k.a KANDEM grew from being one of the pioneers of arc lighting at the start of the 20th century to become one of the major international suppliers of, what we would term today as, architectural, industrial, contract and public lighting, including building the spotlights which helped the NSDAP set their Nürnberg rallies in such a favourable light. Around 1927 KANDEM began a cooperation with the Metal Workshop at Bauhaus Dessau, a cooperation which saw the likes of Marianne Brandt, Hin Bredendieck, Alfred Schäfter or Hermann Gautel develop innumerable designs for the company; objects which as presented in Bauhaus_Sachsen demonstrate the most satisfyingly thought through and technically realised solutions to the numerous challenges they were expected to conquer; and objects which through the royalties they brought in, effectively, kept Bauhaus Dessau afloat. Bauhaus_[Saved by]Sachsen.

In addition Bauhaus was closely related to the textile industry in Sachsen, companies such as Polytextil in Seifhennersdorf, Baumgärtel & Sohn in Lengenfeld or the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau cooperating throughout the 1920s and 30s with the Frauenabteilung Weaving Workshop, and also the Sächsisch publishing industry provided both a platform for Bauhaus and utilised the opportunities afforded by the new ideas of the new generation, something most visually demonstrated in Bauhaus_Sachsen through the contributions by Bauhäusler to the Leipzig based magazine "die neue linie", "the new line/route/way", an almost programmatic title for a lifestyle magazine of the period, but also through, for example, the typography of Leipzig born Jan Tschichold.

While commerce of a different kind is underscored in the presentation Graphic Cabinet, a presentation which not only allows for a overview of the wide variety of artistic approaches practised at Bauhaus/by Bauhäusler, but for all allows for considerations on the many galleries, for all in Dresden, who exhibited and represented Bauhaus artists and thus helped disseminate their works.

Beyond, or perhaps better put, in context of the Bauhäusler and their works, a very pleasing addition/extension is provided by the exhibition catalogue, a work which is, very intelligently and satisfyingly, geographically structured; discusses Bauhaus in Sachsen in context of 22 towns in the State: taking the reader beyond the big three Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz, the latter featuring several essays on Marianne Brandt, to smaller locations such as Glauchau, Zwickau, Waldheim, Plauen and also those such Hoyerswerda who only appear in the story post-War, in Bauhaus_DDR and which thus links Bauhaus_Sachsen very nicely into Shaping everyday life! Bauhaus modernism in the GDR at the Dokumentationszentrum Alltagskultur der DDR, Eisenhüttenstadt, not least because as an exhibition Bauhaus_Sachsen, largely, stops with the war.

Parallel to the story of the Bauhäusler and their work runs a discourse which could be surmised as Bauhaus_Grassi. In many regards a, what one would today term, early adopter, the Grassi Museum has/had a long relationship to and with Bauhaus and Bauhäusler, one which, as the exhibition explains, begins in 1919 when Walter Gropius served on the selection committee for the institute's Design and Model fair, and one that became more formalised when Bauhaus took a stand at the 1924 Grassimesse; the start of story which saw not only the school regularly present itself at the Grassimesse, arguably most interestingly in 1929 with the so-called "Bauhaus Room" a contemporary interior which reflected new director Hannes Meyer's "Necessities not Luxuries" ethos, but also the start of regular participation of individual Bauhäusler at the trade fair. In this context Bauhaus_Sachsen presenting objects such as, and amongst many, many others, Wilhelm Wagenfeld's glass tea service for Schott & Gen. Jena, numerous porcelain objects by Marguerite Friedlaender, textiles by Margaretha Reichardt, a deeply troubling table lamp by Christian Dell for Gebr. Kaiser, deeply satisfying plastic cups by Christian Dell for Römmler AG and various items of furniture including Selman Selmanagić, Herbert Hirche & Liv Falkenberg's Seminarstuhl through VEB Deutsche Werkstatt Hellerau, and thus an object which reminds us all that post-War Bauhaus_Sachsen became Bauhaus_DDR, and that (at least initially) the two enjoyed an altogether different, less cordial, relationship.

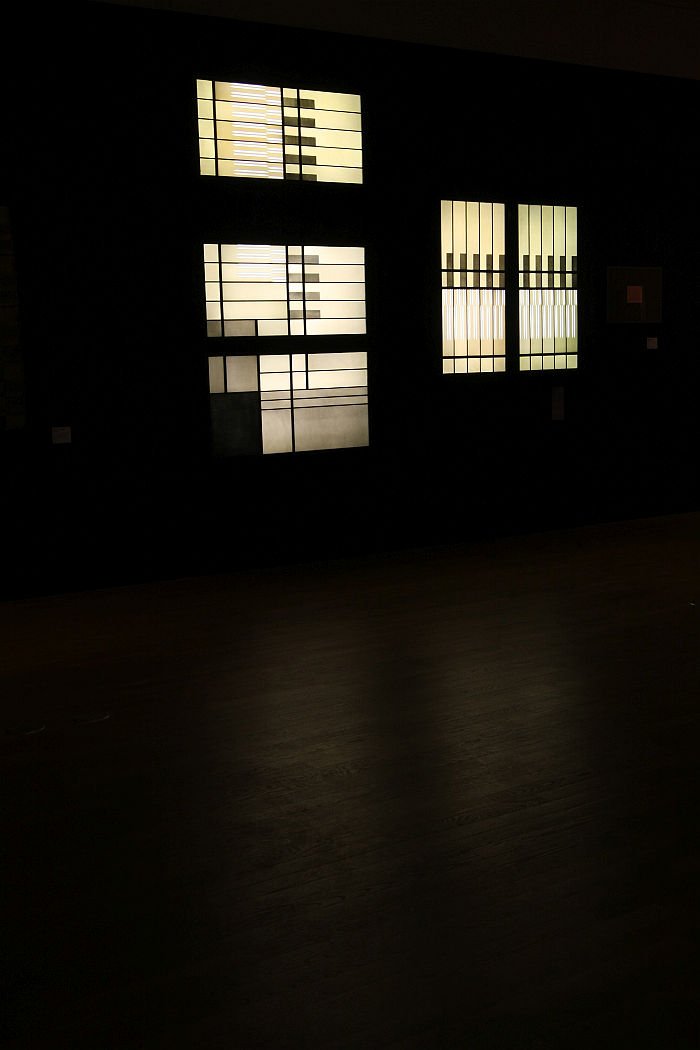

Then there is the Josef & Anni Albers, two non-Sachsen but two creatives who through their numerous contributions to the Grassi Museum have a strong connection to the institution, not least through the windows Josef created in 1926, potentially in close cooperation with Anni, and which grace the Grassi Museum's main staircase. Destroyed in the Second World War, the windows were painstakingly recreated in 2011 and today are one of the more subtle joys of any visit to the Grassi complex.

Beyond Bauhaus_Historic, Bauhaus_Sachsen also features contributions from eight contemporary artists which take position to and/or with Bauhaus, including an imagining of the, never published, 2nd Bauhaus "New European Graphics" monograph by Felix Martin Furtwängler, experiments with Bauhaus ceramics by Lutz Könecke and Alexej Meschtschanow's installation Boppard Couch, and a work which regardless of how one understands its reflections on the steel tube furniture that popularly characterises Bauhaus, is the first reference to Michael Thonet we've encountered thus far in Bauhaus100. Which honestly surprises us, given the obvious connections between the formal and constructional developments of Michael Thonet in the 19th century, and those of the avant-garde of the early 20th century, we'd genuinely expected more Bauhaus_Bentwood this year. However we suspect we will get a chance real soon to rectify that, watch this space as it were.

Featuring an exhibition design which achieves that trick of appearing to increase the volume of the Grassi's main exhibition hall, Bauhaus_Sachsen's subdivision into bite size explorations of the myriad themes that invariably surround an institute like Bauhaus allows for a sprightly exhibition, where the switching of genres and continual confrontation with new names avoids the feeling of wallowing, while the scenongraphy with its near absence of extended lines of visibility and ever changing shades and hues creates the impression of being in space much larger than you are, and thus adding to the feeling that one is moving quickly through the space. Although you are ambling. There's a lot to see. The concise bilingual German/English texts introducing the contexts in a clear, accessible fashion and thereby ably supporting the exhibits, even if one can't held thinking trilingual German/English/Sächsisch would have been more appropriate.

If we did have one complaint, rare as such things are, it would be that in the exhibition the biographies of the designers are a little neglected. In the fulsome, bilingual, catalogue that is more than rectified, but given that many of those featured are far from being as well known as a Gropius, a Breuer, a Feininger or indeed a Brandt, and that one of the aims of 2019 must surely be to expand the Bauhaus biography and thereby allow for an expanded understanding of the school, a little more information in the exhibition would be useful, as it is one has to note the names... to check up later in the catalogue, ideally accompanied by a preferred beverage.

If we did have two complaints, sorry, it would be that the geography so pleasingly realised in the catalogue is absent in the exhibition, a map, an interactive map?, indicating the locations and relevance would have been helpful. Not least because we can't imagine most visitors will actually know where a Großbothen, a Limbach or a Crimmitschau are to be found. Which on the other hand makes the catalogue an excellent starting point for planning an architecture/design tour through Sachsen. Whereby, it's possibly advisable to hire a bilingual German/Sächsisch local as a translator.

Not that our two complaints detract in any way from the exhibition. Far from it. A very coherent and logically structured exhibition which pleasingly, and unlike this text, ignores the easy cliches, yes familiar objects are there, they need be, but we'd argue the great majority of the works will be new to a majority of visitors, Bauhaus_Sachsen not only neatly underscores the important role industry in Sachsen played in allowing for the dissemination, the establishing, of the formal, functional, material, constructional ideals of the school, nor only the role played by the Grassi Museum in the same, nor only the depth and variety of work produced by Sächsisch Bauhäusler, but also the depth and variety of work produced by Bauhäusler, and thereby allows for a understanding of what Bauhaus is/was that although specific, is wider than that which an unfiltered Bauhaus focus would/could normally allow.

Or put another way, much like understanding spoken Sächsisch involves following the speaker closely and with your full concentration, so to can following the Sächsisch accent in Bauhaus, closely and with your full concentration, allow one to not only better understand Bauhaus_Sachsen but to better approach a more realistic, and thus more rewarding, understanding of Bauhaus_Universal.

Bauhaus_Sachsen runs at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig, Johannisplatz 5-11, 04103 Leipzig until Sunday September 29th.

1allensbacher berichte Nr 4 2008, https://www.ifd-allensbach.de/uploads/tx_reportsndocs/prd_0804.pdf Accessed 19.04.2018

2This might not be 100% true. Or even 1% true. In our understanding Martin Luther did communicate in Sächsisch, however historic Sachsen and contemporary Sachsen are very, very different places..... But it is helpful in the construction of our argument, and so in the interests of rhetoric more than fact we're stating it, just please don't quote us on it........

3Christian Pudor, Der Teutschen Sprache Grundrichtigkeit und Zierlichkeit, Cölln an der Spree, 1672

Full details, incluing information on the accomanying fringe and film programme, can be found at www.grassimuseum.de