"Form should not be finite but should be amorphous, so that the experience within is loose, meandering and multiple" - Balkrishna Doshi1

With the exhibition Architecture for the People the Vitra Design Museum explore Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi's understanding of, belief in and approach to realising the amorphous, the social, the humane, in architecture.

An Indian architect who has built exclusively in India, Balkrishna Doshi is, it would be fair to say, not a household name in Europe.

And that despite being the 2018 Pritzker Laureate, and thus recipient of one of architecture's most important international accolades.

And that despite a career which not only, in many regards, began in Europe, was in many regards (initially) influenced by Europe, but which, in equally many regards, is as relevant for Europe as it is for India. As relevant for the people of Europe as for the people of India.

Or put another way......

Born in Pune on August 26th 1927 Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi initially studied painting at the city's Institute of Modern Art before a tutor advised he should consider architecture; advice Doshi wisely followed, and which led him in 1947 to enrol in the Sir Jamshedjee Jeejeebhoy College of Architecture in Mumbai. Unsatisfied with both method and content of the education in Mumbai Doshi moved to London in 1951 with the aim of joining the Royal Institute of British Architects, and where fate crossed his path. Not in London but in the rural calm of Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, where in July 1951 the 8th Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne, CIAM, was being staged, and where Doshi learned that Le Corbusier had been commissioned to build the new city of Chandigarh in northern India.

"Can I join the team?" Doshi asked.

"You would not be paid for 8 months. If you want to come, come", the reply2. A reply which indicates little has changed in the world of architecture since the 1950s. And an offer Doshi accepted.

Following three years in Paris, a time during which he not only developed works for Chandigarh and Ahmedabad, but both became acquainted with Le Corbusier's floating concrete block Swiss Pavilion at the Cité Internationale Universitaire, and the similarly weightless concrete works of Oscar Niemeyer, Doshi returned to India in 1954, where, and in addition to supervising the construction of Le Corbusier's projects in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad, he established his own practice, Vastu-Shilpa, and from where in the intervening 60+ years Doshi has realised 100+ projects ranging from small private houses over civil and commercial buildings to extensive urban planning.

In 1961 Doshi was involved with both the planning and realisation of Louis I. Kahn's Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, and in the initial development of the National Institute of Design, a institute whose founding was based on Charles and Ray Eames' "India Report", before in 1962 he established the School of Architecture, Centre for Planning and Technology, CEPT, and thereby also establishing his career as an academic, teacher and author. A career that has seen him serve as guest professor at numerous international institutes, present papers at numerous international conferences and receive numerous international awards, including in March 2018 the Pritzker Prize.

Not that the Pritzker Prize is the reason for Architecture of the People. As everyone at the Vitra Design Museum is (very) keen to underscore. Rather, and as older readers will remember, much as the Vitra Design Museum's staging of Alvar Aalto – Second Nature, implausibly, soon after Vitra's takeover of Artek was a matter of good fortune rather than reaction, the planning for Second Nature having began long before the acquisition, so the planning for Architecture of the People began long before Doshi was awarded the Pritzker. Events, once again, simply overtaking the curators. However, should the Vitra Design Museum demonstrate such astute foresight for a third time, we will become officially suspicious.

Not, we hasten to add, that the museum are keen to deny the connection with the Pritzker because they fear people will think they selected the subject based on some short term, commercial strategy; much more they are keen to underscore the actual reasons why the decision for a Balkrishna Doshi solo exhibition was made. Reasons the awarding of the Pritzker Prize tends to underscore as being valid. And reasons explained and discussed in the course of Architecture for the People.

Based on the Indian National Gallery of Modern Art's 2014 exhibition Celebrating Habitat: The Real, the Virtual and the Imaginary, Architecture for the People presents a thematic presentation of Doshi's oeuvre divided into four chapters, four chapters which although all reflecting different aspects of Balkrishna Doshi's understandings of architecture and his approach to giving form to those understandings, are all inter-related and inter-dependent; if you will an inter-relationship and inter-dependency that stands representative of Balkrishna Doshi's holistic understanding of architecture, an understanding described in the first chapter as reflecting an "architect's duty to society."

The thematic focus of the opening chapter is the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, CEPT, in Ahmedabad, an institution to which Doshi has not only contributed to the educational content and method, to that which dissatisfaction with saw him leave the College of Architecture in Mumbai, but for which he has also developed numerous buildings including, and amongst others, the Kanoria Centre for Arts, the School of Design or the Amdavad Ni Gufa art gallery: a project developed in cooperation with the artist Maqbool Fida Husain, a project which as a model dominates the first exhibition hall, and a project which in terms of its genesis, the movement both physical and cognitive in allows, its combination of computer aided design with local construction techniques, its reference to local tradition and its innovative solution to the challenges of the prevailing climate, in many regards sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition.

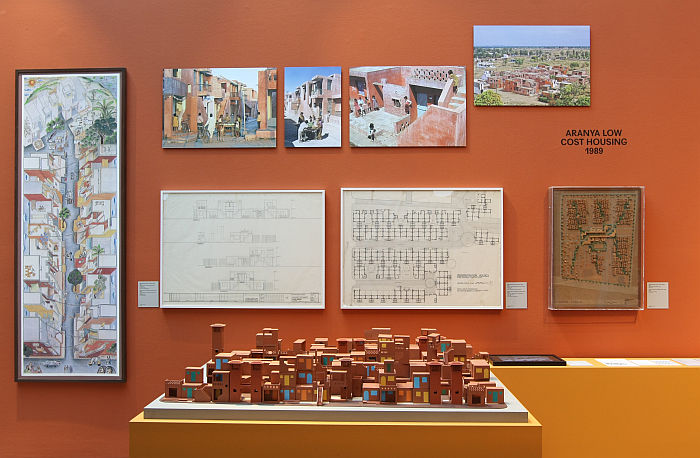

From the large scale Architecture for the People moves to the domestic and Doshi's numerous housing projects, including a visit to his own home, Kamala House in Ahmedabad; and thereby not a frivolous and hagiographic visit, but much more a (near) necessity for the exhibition's narrative: architects invariably practising in the privacy of their own homes their beliefs more exactly, or at least approaching a more faithful realisation of their beliefs at that moment, in their own homes than they do in more public commissions. The home representing Architecture for the Person, in a form that can be applied, transposed, to the People. Something underscored in projects such as the Aranya Low Cost Housing community in Indore, in context of which a pre-fabricated modular construction system was conceived with the aim of allowing the residents to define their own homes according to their own requirements, to paraphrase Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, according to the organisation of their own ways of life, and therefore move towards providing residents, the community, with a sense of ownership, identity and empowerment, rather than just somewhere to live. And a sense of empowerment which runs through Architecture for the People, and which the curators inform us is/was inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, a not unimportant figure in the late-/post-colonial India in which Doshi grew up.

Reflections on Doshi's own daily realities are continued into the third chapter, a space dominated with a presentation of his own office, Sangath, a work which through Doshi's characteristic use of concrete and brutalist tendencies would tend to exclude all notions of the amorphous; but which exactly through Doshi's characteristic use of brutalist tendencies, and through his associated considerations on the function of the building beyond its mere physical structure, the function of the building beyond its primary one in that space and time, the response to the local environmental conditions, the choice of materials and construction process, the relationship to the environment in which it stands speaks very much of the amorphous. And considerations discussed further in projects such the Mahatma Gandhi Labour Institute, Shreyas Foundation Comprehensive School or the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore.

In the final chapter the individual components of the preceding three are, in effect, brought together in the question of urban planning and how can we develop better, more responsive and relevant cities, cities which impact positively on individuals, communities and the environment? Questions answered by Doshi in works such as, and amongst others, his 1984 masterplan for Vidhyadhar Nagar, a 350 hectare energy-conscious development for 400,000 residents on the edge of Jaipur.

And questions which underscore the contemporary, global, relevance of many of the themes and considerations inherent in Doshi's local, site-specific work.

Or put another way, viewing Architecture for the People one slowly comes to the very obvious realisation that much as Brexit can't be resolved by the English Conservatives alone, maybe the better approach to the challenges of contemporary European architecture and urban planning is to be found beyond ones own blinkered field of vision, beyond an unshakable belief in the superiority of your traditions and institutions, and through embracing global ideas, through embracing the ideals and understandings of others, others imbued with alternative traditions; or more accurately, others imbued with ideas, ideals, understandings formed from approaching answers to the same questions in an alternative location, in alternative traditions, and with an alternative philosophy. That we in Europe can learn from other continents, other countries, even those we may tend still to view with the jaundiced eye of the colonialist.

Which isn't to say Balkrishna Doshi has all the answers. No-one is claiming he does. Nor is anyone claiming his ideas should be transcribed 1:1. But does mean that Balkrishna Doshi's work allows for a differentiated insight into how solutions to contemporary, global architectural and urban planning problems could be approached, how architecture can be humane and responsive to the human condition, how architecture can support and develop communities as much as house them, how architecture can be as much of the people as for the people.

As ever with architecture exhibitions Architecture for the People must contend with the age-old problem of presenting something on the scale of architecture, for all the scale of many of the projects developed by Doshi, in the constraints of a museum. Something the Vitra Design Museum have approached through on the one hand by keeping the presentation relatively light, there is a lot on view, a lot of models, sketches, photographs and documentation, but there is also a lot of space, both physically in the exhibition galleries and also in terms of content, as an exhibition it doesn't try to cover all bases, does enough, then skips on, and consequently the presentation is approachable, engaging and coherent.

The sense of space generated by the exhibition layout is ably supported by a bold colour scheme, one which in addition brings a compelling sense of movement, a sense of movement another use of colour ably supports, albeit in that it interrupts it; the numerous vibrant collages created by Doshi for his his projects: collages based on traditional Indian art techniques and which introduce a whole new world of drama and poetry to the staid genre of architectural drawings, collages which are one of genuine joys of Architecture for the People and collages which in their innate attraction and distraction provide for a form of release from the narrative, cause you to momentarily forget where you are/were, to lose yourself in the colour, forms, scenography, and thus allows you to move on afresh.

With their models, sketches, photographs and documentation architecture exhibitions can be daunting, they certainly always terrify us, we never approach one without a nerve-shattering dose of trepidation. Important however is to remember that no-one is asking you to write a critique on the works, you'll notice we haven't. Nor are you expected to leave an exhibition with a perfect understanding of the architect, we haven't, in many regards you can't, for that you need to experience not only them but also their works personally. However you should come away from an architecture exhibition not only keen to learn more, with a new hunger, but for all with a sounder, wider, differentiated and challenged understanding of the role and function of architecture, what architecture is, can be, should be, must be.

Balkrishna Doshi. Architecture for the People provides for just that.

"I didn't know I was working for the people!" announced Balkrishna Dohi on his reaction to hearing the exhibition title.

And in many regards he wasn't. Isn't.

Much more, and as Architecture for the People coherently explains, his interests are/were much more fundamental, are/were much more about the relationship between a building and its user, about the myriad contexts in which a building exists, about temporality, about space, identity, empowerment, responsibility, equality, being sensitive to local vernacular traditions but not being afraid to adapt them, modernise them, where that is necessary. At the exhibition opening the curators made regular reference to the sustainability of Doshi's works, not just in environmental terms but also cultural and social, that the buildings remain relevant over time. And through not only understanding the need for such, but understanding how to achieve such, how to achieve an amorphous architecture, arises an Architecture for the People.

Or perhaps more accurately put, and if we're smart enough to understand the relevance of Balkrishna Doshi's oeuvre, an Architecture for the Peoples.

Balkrishna Doshi. Architecture for the People runs at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday September 8th

1Balkrishna Doshi, Everything is interrelated in David Pearson, New Organic Architecture: The Breaking Wave, University of California Press, 2001

2Balkrishna Doshi. Architecture for the People, Catalogue, Vitra Design Museum, Wüstenrot Stiftung. 2019

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found www.design-museum.de