The 1920s was in many regards a decade that promised so much, achieved so much, but which was then overtaken by political and economic events before it could cement that which it promised and achieved, and which therefore remains hanging, almost stranded, in history. Somehow unfulfilled. And which with its popular image as as roaring, golden, age also appears a little too joyous, a little too optimistic, sandwiched as it is between the horrors and loss of two wars.

But then in the course of the Années folles, who could have foreseen that the real folie stood before us.

With their exhibition Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station - New Building and New Living in 1920's Halle the Stadtmuseum Halle explore and explain the decade in the context of daily life in the city.

Approaching Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station - New Building and New Living in 1920's Halle the obvious comparison is to and with Moderne am Main 1919-1933 at the Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt; yet whereas Moderne am Main sets out to explain how the region around Frankfurt influenced developments of the 1920s and 30s, Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station is much more about how developments of the period influenced Halle, how they were received and experienced in Halle and how they influenced, changed and impacted on the city and the life of its inhabitants.

Which, yes, sounds very provincial. But (a) it is a Stadtmuseum, City Museum and (b) only if one forgets Halle's importance and relevance to the period. If one forgets, for example, that following the arrival of Paul Thiersch at the city's Handwerkerschule, the contemporary Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule, in 1915, Halle established a reputation as a centre for a more reformist understanding of art, architecture and design education, a (regional) reputation fortified in 1925 not only with Bauhaus's move to nearby Dessau, but the fact that several Bauhäusler switched from Weimar to Halle rather than join Bauhaus Dessau. The fact a straight line from Weimar to Dessau passes through Halle being more than a geographic anomaly.

While beyond the close association with two of the most important creative schools of the period, Halle also sits in a region that practised and advanced much of what was being experimented in the such schools; be that through local industry who were responsible for much of the technical impetus for the aesthetic and functional changes of the period, or in terms of the new buildings realised in Halle in the inter-War years. And indeed those not built; the 1927 competition for the, ultimately unrealised, Stadtkrone cultural centre attracting entries from the likes of Walter Gropius, Peter Behrens, Wilhelm Kreis, Hans Poelzig or Paul Bonatz.

And thus only if one forgets that Halle was one of the most important centres in the region: indeed, when it opened in 1927 the contemporary Leipzig-Halle Airport was known as Halle/Leipzig Airport, in the 1920s Halle was deemed the more important of the two, the one you were more likely to travel to.

Consequently, understanding how a city as closely related to the changes of the period as Halle was existed in the 1920s, can help us approach a more realistic understanding as to how the developments of the decade impinged on daily reality.

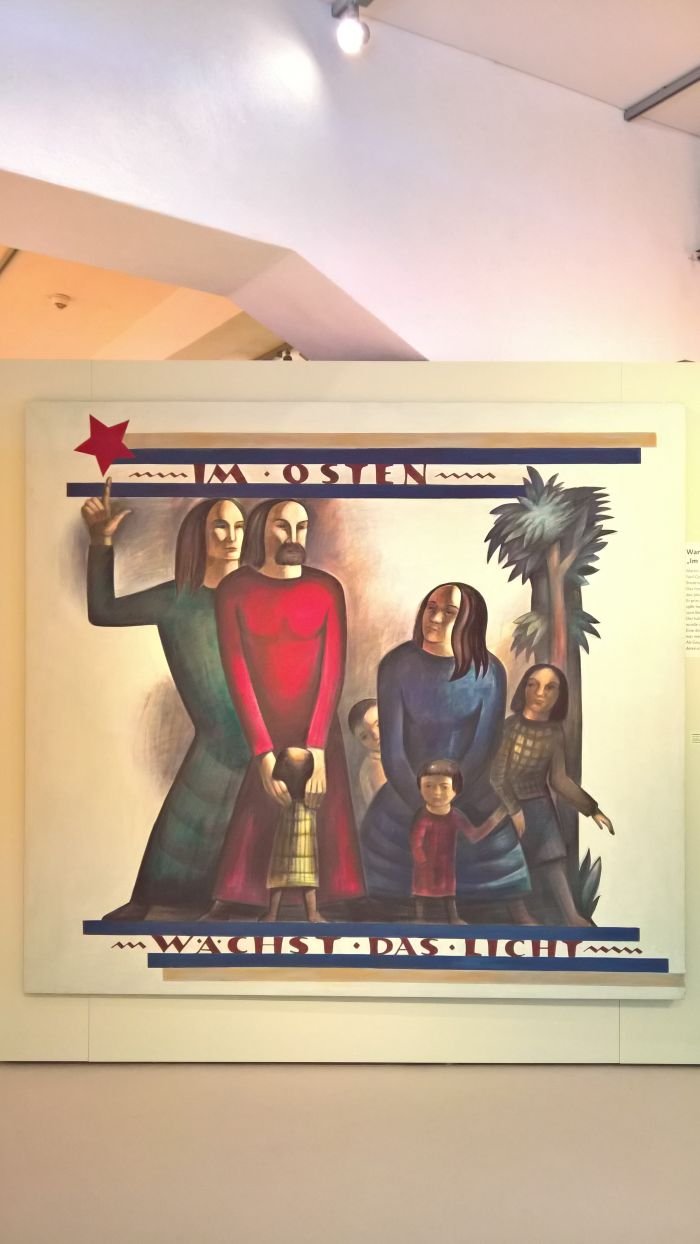

Despite the apparent unequivocality of the exhibition title, the Small Apartment, Department Store and Power Station are less the focus and much more delineate the exhibition into the domestic, commercial and civic aspects of the period, aspects which are explored in ten brief sections, beginning, logically and pleasingly, with a definition of "Modernism", a definition which takes the position that "Modernism" is often used as a synonym for the 1920s, and is generally used to imply a period of change, a period of advance, but also a period that can leave people feeling insecure and exposed.

A thus a very open and honest definition, and one discussed in more detail in the following nine sections.

Among the many important changes of the 1920s few were as widespread and universal as those in housing. As oft discussed in these pages, throughout Europe the industrialisation of the late 19th century saw ever increasing urban populations, placing ever greater stress on housing supply, and a situation the First World War exacerbated. And a problem that was, generally, tackled through the construction of housing estates on the edges of cities, estates of standardised blocks containing flats with although compact were conceived to be maximise the ingression of light and air, to be easy to maintain and hygienic and which made use of latest developments in not only materials, but also technology, such as central heating and electricity. And such was the case in Halle where for all in the south of city new estates and developments arose such as Luthersiedlung, Vogelweide and the so-called Gartenstadt Gesundbrunnen, through the middle of which runs the 850m long Pestalozzi Park as a near textbook example of the new thinking on urban planning evolving in the 1920s and the improved understandings of the relationships between housing and health and the need to plan cities that created positive environments for residents.

But it wasn't all Small Apartments, the 1920s also saw in Halle, as elsewhere, the realisation of increasing numbers of villas as the economic advances of the decade saw the middle class move ever upwards. Among the examples presented in Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station is the highly idiosyncratic Villa "Zu den Sieben Waben" by and for architect Wilhelm Ulrich, and a work based on, as Germanophones will have suspected, a repeating hexagon form, and which, yes, does resemble a honeycomb. But then why not, bees seem perfectly happy with the arrangement.

In addition to the houses themselves Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station also includes examples of the new, contemporary fixtures and furnishings of the period, whereby one notes much of the furniture is anonymous, often charming and engaging, but of unknown provenance, although the assumption would be some small local workshop; and thus a very nice, and timely, reminder that beyond the popular belief that everyone in the inter-war years was consuming certain types of furniture from certain manufacturers, there exists a contradictory reality.

In addition to changes in housing the 1920s were also a period of rapid change in terms of consumption; on the one hand new materials and production processes were making ever new objects possible, on the other new formal ideals that had been evolving since the end of the 19th century became increasingly established, and on the rare, and thus all the more important third hand, the 1920s also saw, arguably, the heyday of the department store. Of which 1920s Halle appears to have had numerous, the exhibition featuring institutions such as A.Huth, J.Lewin or C.F.Ritter in addition to specialist stores such as the shoe shop Friedrich Oehlschläger or the vitner's Pottel & Broskowski, and businesses who, as the exhibition explains, and the (German) title alludes to, largely traded from buildings created with a pared-down, reserved, self-confident and thoroughly contemporary Neue Bauen, New Objectivity, understanding.

In addition the regular mention of the Jewish faith of many of the Halle retailers also very nicely allows for an important, and natural, unenforced, reminder of the position Jews occupied in Germany of that period, and how a lot of that history is today lost, both physically but also through a dialogue that tends to focus on the horrors of the holocaust rather than the simple daily reality of pre-War German society. The former is very important, the latter however an important supplement, helping as it does to underscore the social, cultural, economic and political structures the paranoia, fear, prejudice and false information of the 1920s destroyed. Something particularly important as our own age of paranoia, fear, prejudice and false information threatens ever more the simple daily reality of our societies.

Similarly instructive for our own age is the information that between 1919 and 1923 the electricity demand in Halle increased by some 500%. Which is just ridiculous!! But very neatly underscores not only just how radically life changed in the 1920s, how electricity went from being something new to something everyday, but for all that social and cultural change demands new civil infrastructures.

To cope with their new energy demand Halle built a new coal fired power station at Trotha in the north of the city, a work by Wilhelm Jost and which with its brick facade, plentiful windows and implied classic ornamentation is a work as aesthetically of its day as it is functionally. And thereby one that can't be a solution to the ever increasing electricity demands of our ever expanding global population and networked digital age; for today we understand that building ever more power stations and burning ever more fossil fuels, ain't the answer. We need both new power sources and less electricity intensive objects.

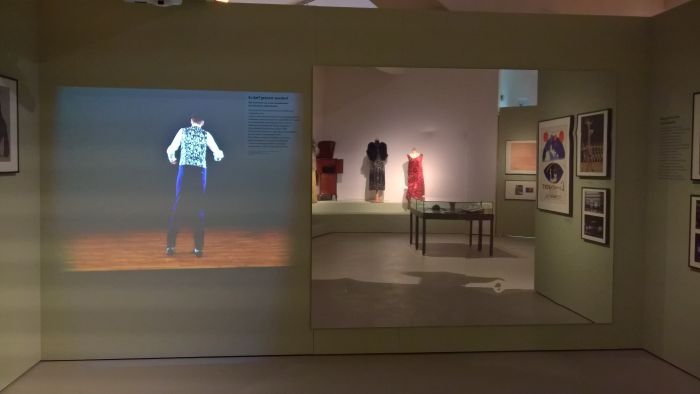

In many regards the reasons for the for the new Power Station can be found in the Small Apartment and Department Store, but as the exhibition explains there were others, not least the burgeoning social life of the 1920s. Driven not only by the economic advances of the decade but also, as the curators point out, by improved working conditions, including the introduction of the 8 hour day and statutory holidays entitlement, ever more workers had ever more opportunities to break out of their daily routines through visits to coffee houses, sporting events, the cinema - of which we learn Halle had once 19 - or through music and dancing. Including the Charleston, a dance that almost stands as a synonym for the 1920s .... and which visitors are invited to try/learn; a short instructional video taking you through the basics. No, we didn't.

In addition Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station features short considerations on subjects such as schooling, manufacturing, clothing or the establishing of the office block as a place to coordinate the increasing complexity of the everyday, and something pleasingly exemplified by, and amongst other objects, a tubular steel frame desk by Erich Dieckmann for Cebaso, arguably one of the "lost" Thüringen based manufacturers of the inter-War years, and a desk which features an absolutely delightfully conceived and realised slide out extension for a typewriter. And next to which visitors are offered the chance to use a typewriter. A short description explaining how it works and what to do!! As students we wrote most all our reports and essays with a typewriter, only submitting our final dissertation as a computer print out because the rules demanded such. Today, a typewriter is an object one has to explain to visitors in a museum exhibition!!

But then, and as with the light switch in the exhibition täglich geöffnet in the nearby Burg Galerie im Volkspark, the inclusion of the typewriter is another glorious example of progress, of things that were previously ubiquitous becoming superfluous, and being replaced by something equally ubiquitous. Which will also in time become superfluous. And for all that one needn't fear change as long as it is meaningful change: we're typing this on a train, and thankfully not with a typewriter.

Featuring a clearly laid out, comprehensible exhibition design complemented by clear and concise (German only) information panels, Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station develops an accessible, informative narrative, one where each of the ten chapters is self-contained, but which all inextricably link into and through one another; and a narrative which through its exploration of how the changes and developments of the period were both effected in and thereby affected Halle allows for a wider and more realistic perspective on the period, one that helps you move towards a better understanding of where the 1920s could have taken us, had they been given the chance, or arguably had they not become afraid and wary of the realities that they themselves had opened. And in doing so counsels us to, yes, critically question the changes of our times, and certainly to challenge them, stand up to them, but never to fear them.

But for all as an exhibition Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station invites, nay demands, you to go out and find the locations, find the traces of 1920s Halle in the contemporary city, and in doing so offers the possibility to not only better comprehend how the 1920s changed urban life, but also to allow for a much more differentiated view of contemporary Halle.

Small Apartment, Department Store, Power Station - New Building and New Living in 1920's Halle runs at the Stadtmuseum Halle, Große Märkerstraße 10, 06108 Halle (Saale) until Sunday June 16th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at https://stadtmuseumhalle.de/