How do we ensure there is sufficient, affordable, healthy, practical, accommodation for our contemporary population and their needs?

Not just a question for today's society but arguably one that has been posed, considered and approached by architects and urban planners since the late 19th century.

If, admittedly, without anyone ever solving the conundrum. Or at least not unequivocally. Or sustainably.

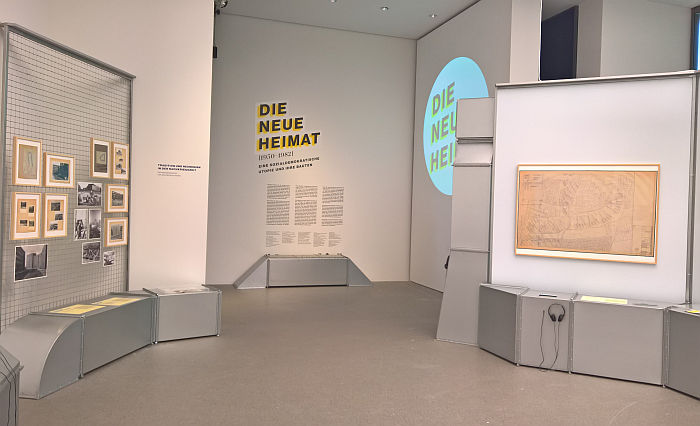

With the exhibition Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982). A Social Democratic Utopia and Its Buildings, the Architekturmuseum der TU München review the (hi)story of the Neue Heimat housing corporation and its efforts to ensure sufficient, affordable, healthy, practical, accommodation for West Germany, and in doing so add to the contemporary discourse.

Tracing its history back to Hamburg, 1926 and the formation by local trades unions of the Gemeinnützigen Kleinwohnungsbaugesellschaft Groß Hamburg, GKB, a housing organisation taken over by the Nazis in 1933, the story of Neue Heimat begins in earnest in 1952 when the Nazi era housing authority was handed over, or perhaps better put, returned to, the German Trades Unions Congress, DGB.

From Hamburg Neue Heimat quickly expanded through a series mergers with other social and communal housing corporations in locations as widespread as Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Berlin (West) or Bremen, so that by 1960 Neue Heimat could boast some 27 daughter corporations managing some 110,000 flats. A number which by 1963 had neigh-on doubled to 200,000. Whereby, and as was underscored at the exhibition opening, the vast majority, as in almost all, the housing was conceived as social, affordable, urban accommodation. And thus in many regards exactly that which we have so many problems developing today.

Whereas the housing Neue Heimat developed may have been social, the motivations of several of its managers were (surprise surprise! (sorry!!)) much more avaricious, and when a Spiegel title story on 08.02.1982 broke a financial scandal within the organisation its days were numbered. Not least because the Spiegel research also unearthed the fact that the organisation was (secretly) heavily in debt.

Over the subsequent decade Neue Heimat was broken up into local housing corporations, and although (almost) all the projects Neue Heimat realised still exist, Neue Heimat itself has long since become an approach to housing construction, provision and management that once was. And a financial scandal.

Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982). A Social Democratic Utopia and Its Buildings is an attempt to better understand just what Neue Heimat was.

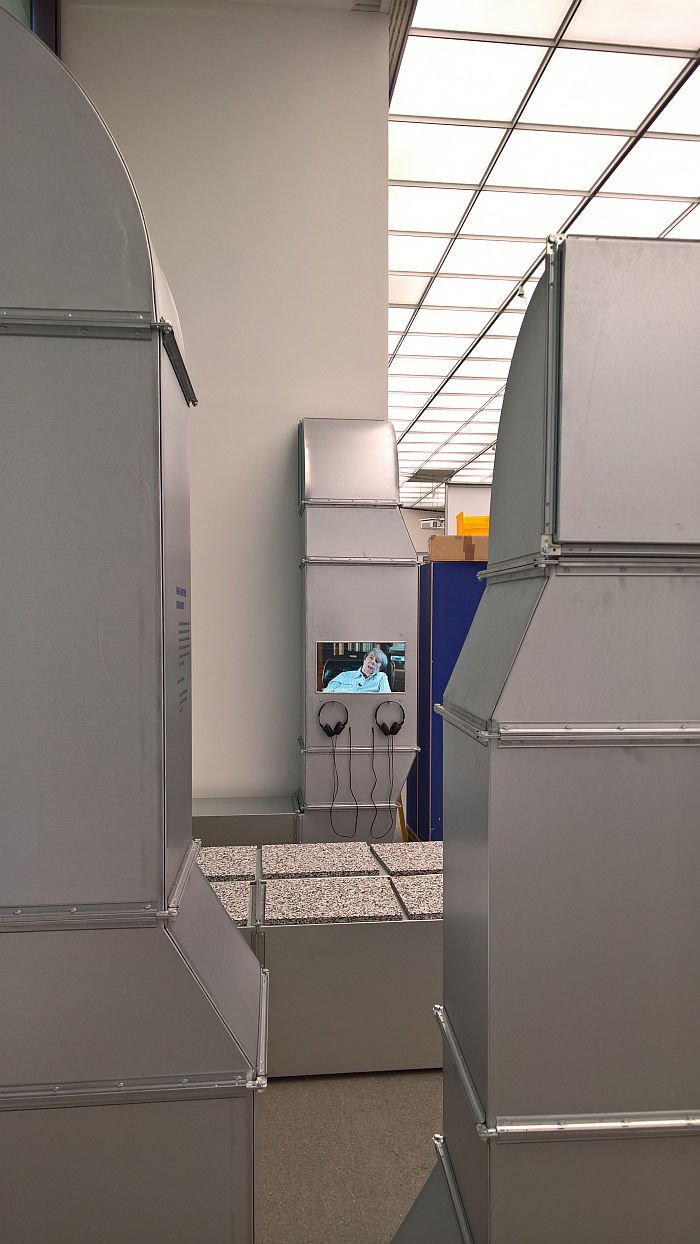

Running more or less chronological, Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982) begins with projects from the early 1950s, predominately in Hamburg such as the estates Hohnerkamp, Barmbek-Nord or Veddel, before moving over the company's rise and diversifications, a story told through a mix of models, photographs, plans, sketches and video interviews before ending with the breaking of the scandal and thus the end of Neue Heimat as an architecture, construction and urban planning concern and its genesis as one for journalists, lawyers and forensic accountants.

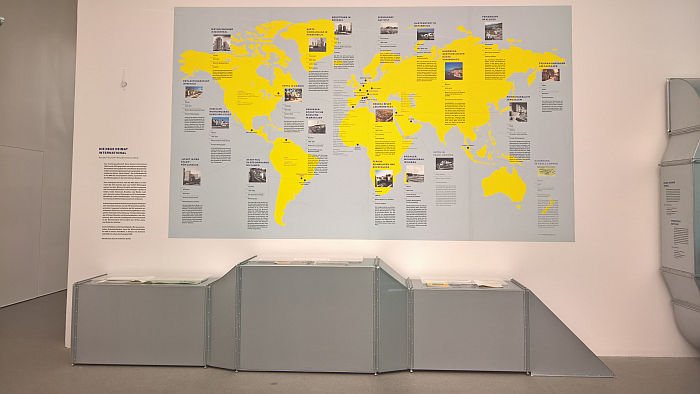

Essentially divided into presentations of individual projects, specifically some 36 from the many, many Neue Heimat realised, as an exhibition Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982) makes very clear the scale of Neue Heimat, or perhaps better put scales: geographic, projects being realised not only across West Germany, but globally, including, and amongst many other locations France, Ghana, Israel and Canada; generic, Neue Heimat realising in addition to numerous high rise estates a number garden cities and old town renovations, the latter as exemplified, for example, by Hameln; function, from single family houses to shopping centres, hospitals, conference centres et al; and the sheer number of properties it developed, some 400,000, the largest single project being the 24,600 flats developed between 1967 and 1975 as Munich Neuperlach.

In addition Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982) also makes very clear the central role construction methods played in that which we are somewhat recklessly calling the Neue Heimat approach. While unquestionably architecture and urban planning, Neue Heimat projects were less about the resulting visuals as the efficiency and expediency of the construction method, the functionality of the buildings and the social connections enabled, or at least desired, by the wider planning considerations: and thus in many regards Neue Heimat links neatly back to many of the aspirations and ideals of the inter-War years. Yes, the person of Ernst May as Chief Planner of Neue Heimat from 1954 makes such a connection relatively easy to draw, for all to Neues Frankfurt, but viewing the mass of projects presented, in such close proximity, in Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982), one understands, when not a complete, 1:1, then certainly a deeper comparison. One that goes beyond Ernst May. And one which arguably has its differences in the realities of the decades under consideration.

On several occasions our thoughts also drifted across the inner-German border, not just on account of the claims of the desire to create genuine socially coherent communities inherent in the projects, but also, predominately?, in context of the so-called Elementa construction system developed by Neue Heimat and which allowed for variable floor plans in flats and as such is/was very reminiscent of the variable, adaptable concepts, experimented with by Rudolf Horn and others in context of the Variables Wohnen project in Rostock in the 1970s.

Thoughts which tended to, once again, support our belief in our much touted "enduring logic and magnificence of modular construction"

Beyond its central focus on the buildings and estate plans Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982) also presents short discourses on the Neue Heimat magazine produced to inform both residents and specialists about the Neue Heimat's projects and also present considerations on wider contemporary themes in terms of housing, planning and design, and, and somewhat inevitably, a vehicle introduced by Ernst May, who during his time at both the Wohnungsfürsorgegesellschaft für Oberschlesien and Neues Frankfurt used magazines to disseminate news and research; the gardens and landscaping of the estates as important social, cultural and environmental considerations; and the furnishing of the interiors. Something the Neue Heimat magazine seems very keen to have presented as being frightfully contemporary, photos showing a profusion of works by the likes of Verner Panton, Charles & Ray Eames or Eero Saarinen in addition to numerous Kartell objects including several modular Componibili storage units. Images which remind(ed) us of the profusions of tubular steel in photos of inter-War interiors. And pose similar questions as to how representative they actually are/were......

Just as important as the historical review of Neue Heimat is the presentation of the so-called Grosssiedelungen der Neue Heimat project which saw Munich based photographers Ulrike Myrzik and Manfred Jarisch document 14 of the larger Neue Heimat estates, both in photos and through comments and opinions from contemporary residents: how an urban planning project ages being every bit as important as that which the planners intended. There are, as one would expect, numerous negative comments and opinions.

Comments and opinions, negative and positive, which pose the obvious question, what can Neue Heimat contribute to contemporary discourses on affordable housing provision?

Arguably nothing.

Or at least not yet.

The first architectural review of Neue Heimat since its collapse Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982) is by necessity much wider than it is deep, and while it provides for a very pleasing, easily accessible and clearly constructed overview of what Neue Heimat was, what they hoped to achieve and how they set about that: it doesn't reach a depth that allows for any serious contemporary interpretations to be made. However does very clearly indicate that there are in all probability lessons that can be learned.

That we can, potentially, learn from Neue Heimat being however a case of luck. Or possibly fate. As Ullrich Schwarz, head of the Hamburg Architecture Archive, one of the exhibition's co-organisers, explains, as the winding up of Neue Heimat was approaching its conclusion the archive received a tip-off that large quantities of Neue Heimat material were heading for, well, the tip. A quick reaction rescuing documents, films and some 25,000 photos, without which reconstruction of Neue Heimat today would have been neigh on impossible. At least not with any degree of competence.

That in late 1980s Hamburg there could have been those who wished that Neue Heimat would forever vanish is more than conceivable; and is arguably also the reason why since its final demise it has played but a negligible role in considerations on contemporary urban planning. With Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982) the TU München and Hamburg Architecture Archive have brought it back onto the agenda, and now that it is, now that it can be discussed with the advantages of hindsight, by new generations of professionals and against contemporary developments in materials, technology and social understandings, now is arguably an apposite moment to delve deeper into the specifics and see if there are lessons to be learned from the (hi)story of Neue Heimat for the provision of affordable, healthy, practical, accommodation for our contemporary population and their needs.

Over and above keeping a close eye on the managers.

Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982). A Social Democratic Utopia and Its Buildings runs at the Architekturmuseum der TU München, Pinakothek der Moderne, Barerstraße 40, 80333 München until Sunday May 19th

All information panels are in German only.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.architekturmuseum.de

.