"The role of the architect is one of organisation. The house is the considered organisation of our ways of life"1, opined the Austrian architect Margarete Lihotzky in 1921.

And in the course of a long, varied career, she repeatedly demonstrated what she understood by such; including most famously, if somewhat narrowly, in a kitchen design.............

Born in Vienna on January 23rd 1897 as the second of two daughters to civil servant father Erwin, and housewife mother Julie, Margarete Lihotzky was raised in the, relative, comfort of Vienna-Margareten; the family sharing the house of and with her maternal grandfather, the civil engineer Rudolf Bode, and in an atmosphere "full of education, but free from any material pride or intellectual arrogance"2.

Having attended first the local Volksschule and subsequently the Bürgerschule, Margarete Lihotzky spent two years at the Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt before entering the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule - Applied Arts College - in 1915, where, after completing the universal Preparatory Class, she specialised in architecture in the atelier of Oskar Strnad: the first female to study architecture at the Kunstgewerbeschule, thereby making her one of the first practising female architects in Austria. Upon her graduation in 1919 Margarete Lihotzky initially spent six months in Rotterdam as a chaperone for a group of children evacuated from the hunger and chaos of post-War Vienna; using her spare time to both work in the office of a local architect and to study contemporary Dutch building and urban planning practices, for all the garden estates, including attending lectures by H P Berlage, one of the leading protagonists of Dutch reformist urban planning.

Returning to Vienna in the summer of 1920 Margarete Lihotzky cooperated with the garden architect Alois Berger on a competition entry for a Garden and Settlement Complex on the Schafberg, Vienna, the pair being awarded fourth prize for their reduced, standardised, proposal; and a competition entry which led to Margarete Lihotzky taking up a series of positions within the Vienna Siedlerbewegung - Settler Movement - at that time one of the more experimental European urban planning programmes, and thereby positions which brought her into contact with international architectural circles. Including with Ernst May who in November 1925 invited Margarete Lihotzky to join his Neues Frankfurt project. An offer she gladly accepted and which saw her employed in the Standardisation Department where, as she notes, "everything was designed that was repeatable, for example all the doors, all the windows and the whole house"3. Including kitchens. The so-called Frankfurter Küche, a standardised, in-built kitchen which was installed in all Neues Frankfurt flats being that for which Margarete Lihotzky is popularly, if somewhat narrowly, best known.

In 1927 Margarete Lihotzky married the German architect, and fellow Neues Frankfurter, Wilhelm Schütte, taking on the name Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, and upon the demise of Neues Frankfurt in 1930 Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte travelled with Ernst May to Moscow where they developed numerous urban planning and architecture projects. Until the war intervened. Unwilling to return to Nazi Germany, Margarete and Wilhelm initially moved to Paris before quickly travelling on to Istanbul where both found teaching positions at the Académie des Beaux Arts, and where Margarete became involved with the Austrian communist resistance: an involvement which ultimately saw her arrested in Vienna on January 22nd 1941 and charged with treason. Avoiding the death penalty Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky was sentenced to 15 years Workhouse; a sentence she served in Aichach, Bavaria, until liberation through allied troops on April 29th 1945.

Returning to Vienna Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky found that on account of both her war-time activities in the resistance, and her post-war activity in the Communist Party's Bundes Demokratischer Frauen, she was, when not completely denied, then certainly hindered in her access to public contracts, for all the social/childcare projects in which she had come to specialise. Consequently, while able to realise several apartment blocks for the city authority, in the immediate post-war years she predominately developed private commissions, and projects for the Communist Party. However, as the immediate post-war years became distant post-war decades she was increasingly awarded public commissions, including several Kindergarten projects. Beyond her work in Austria, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky spent six months in 1963 in Cuba, and in 1966 six months at the East German Bauakademie in East Berlin, in context of both helping develop plans for childcare facilities, in addition she was active in institutions such as CIAM, UIA and the Internationalen Demokratischen Frauenföderation.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky died in her native Vienna on January 18th 2000, a centurion, and one who had not only witnessed the social, cultural and political developments of the entire 20th century, but one whose contribution to such remains very relevant today

Although Margarete Lihotzky first found a wider fame in Frankfurt, a period that is often the principle focus of Schütte-Lihotzky biography's, in many regards the more important period is the years leading up to her move to Frankfurt, being as it is a period which not only neatly explains where she came from, but also where she could, potentially, have gone. Had the war not intervened.

The story, or at leas our telling of it, begins in 1917 when the then 20 year old Margarete Lihotzky entered, and won, a student "Arbeiterwohnung" - Workers Housing - competition; her entry proposing not only a building complex with an open garden/courtyard in the centre, but floor plans which foresaw separate bedrooms for parents and children and also the separation of the living room/kitchen from the scullery, and the thereby improved hygienic standards.

Interesting as the proposal is/was, just as, arguably more, important is how it was realised: having informed Oskar Strnad that she was planning entering the competition, he advised her that before she began she should go and visit the working class districts to help her better understand the task. Which she did. And although, as she notes, she was aware of something of the poverty amongst the Viennese working classes of the period, that visit not only opened her eyes to the full brutality, but also led her to understand the acute nature of the housing problem, of the total inadequacy of what passed as housing in the slums of early 20th century Vienna.

And that experience also confirmed her desire to become an architect. When she entered the Kunstgewerbeschule she, by her own admission, had no concrete plan as to her future career; and although she quickly moved ever more towards architecture, following the visit to the working class districts she became certain in her mind that she would become an architect, not least because she began to understand architecture as a "service to people", and that "architecture can never be an end in itself, never be just l'art pour l'art"4

Her first opportunity to practice that came in her work for the Siedlerbewegung.

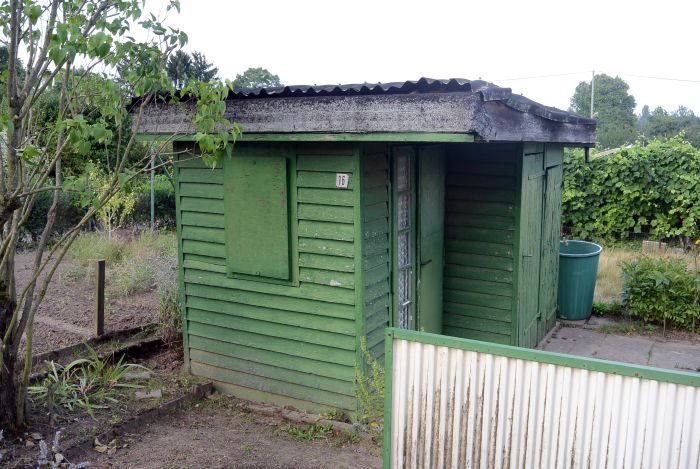

Arising, largely, as a response to the contemporary food and accommodation shortages, the immediate post-war years saw ever increasing numbers of Viennese squatting land on the edge of the city, for all to the west of the city, on the edges of the Wienerwald, building themselves shacks and developing small vegetable gardens, and thereby ensuring something approaching an existence minimum. What began as a by necessity driven, self-help initiative, quickly achieved an official status: the city making ground and building materials available on the understanding the residents contributed their unpaid labour to the building work and organised themselves into self-administered housing associations. To help coordinate the developments, and to advise and assist with the planning and development of the estates, in 1920 Vienna City Council established a Siedlungsamt, initially under the direction of Max Ermers, later Hans Kampffmeyer, and who employed the services of architects such as Josef Frank or Adolf Loos, and also Margarete Lihotzky, who not only designed standardised house types and the associated, and equally standardised, furniture, fixtures and fittings for the interiors, but for all developed her ideas on a Taylorist rationalisation of housework.

The exact moment Margarete Lihotzky became introduced to the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor, to his systematic study of work systems and processes with the aim of increasing efficiency, is lost in the mists of time; however, once introduced his principles struck a chord, and in 1921 she noted that, "several years ago Taylor devised such systems for factories, management, agriculture, etc.. Only in terms of housekeeping could I find no such book, I do not know if such a thing already exists. Of course, this would be of the most far-reaching importance in our settlements"5

Such a book however did exist. Published in 1913 The New Housekeeping. Efficiency Studies in Home Management by Christine Frederick considered just such Taylorist approaches to housekeeping, Frederick opining in an early chapter that "like all other women I thought that there couldn't be much improvement in the same old task of washing dishes."6 She discovered there was. And not just in washing dishes. The secret was a detailed study of what you did and why. The New Housekeeping appeared in a German translation by Irene Witte as Die rationelle Haushaltsführung. Betriebswissenschaftliche Studie in 1921, and in our (possibly inaccurate) reading of the (hi)story, although Margarete Lihotzky did acquire a copy of Die rationelle Haushaltsführung, she didn't have it when she penned her 1921 text, nor was she familiar with Frederick's original: she did however share Frederick's passion for methodically studying household jobs, noting "you should measure each hand movement, the time you need for each action should be measured with a stopwatch, every step should be counted and put, so to speak, on the scales. One should calculate, if something for which one needed ten movements would be possible with eight, and so on..." And that being not just a job for architects but, for "3 groups, housewives, manufacturers and architects, it is an important and responsible task to work together to identify and facilitate this simplest way of doing housework"7

And that on the one hand, and in context of the Siedlerbewegung, because time saved in the home was time that could be invested in the garden, and thereby helping ensure a productive plot, and on the other, as she later noted, "in Europe, it was already foreseeable in the first half of the 20th century that the employment of women would become the normal situation"8 . Consequently necessitating a reduction in household work, something achieved through on the one hand new technology and on the other a rationalisation of house work.9

Just as in 1917 her considerations on the workers accommodation took her to the working class districts, so to did her consideration on rationalisation of housekeeping take her to a location where such could be experienced first hand....... "I visited and carefully considered the kitchen in a railway dinning car"10

Noting that in two rooms each measuring 1.83m by 1.95m two people prepare meals for fifty while in a conventional kitchen/living room with four times as much space one person prepares meals for five people, she poses the question, "could not many house builders and housewives learn from that?"11

Margarete Lihotzky did. And combined that which she learned from the railway dining car, with her experiences of Holland, "their kitchens function better than any other"12, a very obvious fascination for the cleanliness and order of the pharmacy laboratory, applied some Taylorist thinking on housework and brought this all to bear on the kitchens she developed for the Siedlerbewegung; including a, more or less, pre-cast concrete kitchen proposal, designed not only to be easily maintained in itself, but which through the closed connection to the floor made floor cleaning easier. And considerations and proposals which, unquestionably, played a role in Ernst May's offer to join him in Frankfurt.

The rest, as they say, is a kitchen......

Except it is obviously a lot more than that.

Or put another way: when Ernst May asked Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky if she wanted to be part of his team in Moscow, she replied yes, but under two conditions, "My husband must also be offered a position, and that I no longer have to design kitchens, because I am sick to the back teeth of them."13

Which is understandable, by that stage the kitchen, and for all the rationalisation of the kitchen, had been a major focus of her work for over a decade. And tended, and continues, to overshadow that which Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky realised and achieved. Or as she opined, beseeched? in 1984, "I do not want to be seen only as a kitchen architect, that's too stupid"14 And somewhat narrow.

In Vienna she had built family homes, developed a project for a tuberculosis convalescence estate, established and ran the so-called "Warentreuhand" which ensured the those in the settler movement had access to affordable, contemporary furnishings and fittings, and taken her considerations on rationalisation to furniture, developing a series of so-called vorgebaute raumangepaßte möbel, in-built furniture which she claimed could lead to space savings of some 35-40% over conventional furniture, and which found an echo two decades later in George Nelson's Storagewall system. In Frankfurt she developed a concept for integrating flats for the many single women to be found in post-War Frankfurt into the new estates and thereby avoiding the very real risk of social isolation many faced, and also developed plans for childcare facilities, the later being the principle focus of her work in Moscow, and the subsequent decades, including the development in the 1960s of a, though never formally realised modular building system for Kindergarten. And thereby a body of work which reflected not only the evolving technological realities of the periods, but also the evolving social realities, and which always had the user at the centre of their considerations, always considered how the lot of the individual, and by extrapolation the wider community, could be improved.

Yet, despite her protestations, it is for a kitchen that she is most popularly remembered. If not always for the correct reasons.

That the Frankfurter Küche was designed by a female is, as Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky implies, almost to good to be true, and was a fact gladly taken up in the late 1920s for publicity purposes. And oft repeated and underscored today. A modern woman designing for modern women. Perfect! However, as she notes, "until the creation of the Frankfurt Küche, I had never ran a household, had never cooked and had no experience in cooking."1516

The Frankfurter Kitchen wasn't realised from a position of practical experience, far less the practical experience of a woman, but from a systematic assessment of the practical, from detailed considerations on optimal use of minimal space, from a finely honed understanding of standardisation and rationalisation, an acute awareness of the prevailing, evolving, social conditions, and the importance of making use of contemporary technology to enable new standards and new processes. Was about "the role of the architect [as] one of organisation" and for all was about architecture as a "service to people"

And so while Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky should never be remembered as purely a kitchen architect, understanding how and why she became known as one, brings you closer to Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky architect.

Happy Birthday Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky!

1Grete Lihotzky, Einiges über die Einrichtung österreichischer Häuser unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Siedlungsbauten, Schlesisches Heim, Jahrg 2, Heft 8, August 1921, 217 - 222

2Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Warum ich Architektin wurde, Residenz Verlag, Salzburg 2004

3Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Erinnerungen aus dem Widerstand: 1938 - 1945. Mit einem Gespräch zwischen Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky und Chup Friemert, Volk und Welt Verlag, Berlin, 1985

4Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Warum ich Architektin wurde, Residenz Verlag, Salzburg 2004

5Grete Lihotzky, Einiges über die Einrichtung österreichischer Häuser unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Siedlungsbauten, Schlesisches Heim, Jahrg 2, Heft 8, August 1921, 217 - 222

6Christine Frederick, The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management, Doubleday, Page & Company, Garden City, N. Y., 1913

7Grete Lihotzky, Einiges über die Einrichtung österreichischer Häuser unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Siedlungsbauten, Schlesisches Heim, Jahrg 2, Heft 8, August 1921, 217 - 222

8Peter Noever, Die Frankfurter Küche von Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Edition Axel Menges, Ernst & Sohn Verlag für Architektur und technische Wissenschaften, Berlin, 1992

9Yes, and through a greater contribution from men, on a 50/50 separation of household chores, but let's focus here on things Margarete Lihotzky could directly influence.

10Grete Lihotzky, Einiges über die Einrichtung österreichischer Häuser unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Siedlungsbauten, Schlesisches Heim, Jahrg 2, Heft 8, August 1921, 217 - 222

11ibid

12ibid

13Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Warum ich Architektin wurde, Residenz Verlag, Salzburg 2004

14Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Erinnerungen aus dem Widerstand: 1938 - 1945. Mit einem Gespräch zwischen Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky und Chup Friemert, Volk und Welt Verlag, Berlin, 1985

15Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Warum ich Architektin wurde, Residenz Verlag, Salzburg 2004

16We're admittedly a little sceptical about this claim, "no experience in cooking" ??? For example, in those first few months in Frankfurt, alone in a new city, did she only eat out? Every meal? Every day? Never so much as boiled an egg? However, while we don't believe the claim is 100% true, we do believe it represents 100% the distance between Margarete Lihotzky and daily household routines.