Although founded twelve years before Bauhaus Weimar, and despite overlaps in personnel and biographies, it would be incorrect to draw a direct line from the Deutsche Werkbund to the Gropius school, even if a line of sorts can, should, be traced between the two institutions.

A line which serves not only to connect the two but to underscore the role both played in the development of contemporary understandings of formal aesthetics in the first decades of the 20th century, and also the influence both retain over contemporary understandings of such a century or so later.

In context of such considerations, the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge Berlin are presenting throughout 2019 a series of four exhibitions under the title 111/99. Questioning the Modernist Design Vocabulary and which aim to explore various aspects of the development of, well, modernist design vocabulary.

The start being made with graphic arts and the showcase Commercial Design instead of Applied Art?

As oft noted in these pages, the earliest European applied art museums were, in effect, collections of objects and materials conceived with the intention of providing the industrialists, architects and artist of the day with ready access to contemporary best case examples, or at least those selected as such by the specific museum, and/or as a place to seek inspiration for a current/future project.

Established in Hagen in 1909 by the art collector, patron and Deutsche Werkbund member Karl Ernst Osthaus, and arising in many regards from the impetus given by the Deutsche Werkbund, the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe played a very special, unique, role amongst such museums: foregoing a building of its own and instead sending its collection of contemporary best case examples on tours to museums, colleges, libraries and similar institutions throughout Europe, as an, if you will, travelling collection of all that was, or at least according to Karl Ernst Osthaus and his associates, tasteful, contemporary, desirable, relevant, etc...

Following the death of Osthaus in 1920 the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe, bereft of its principle supporter, was quickly disbanded; found however, in many regards, an echo three decades later in the Deutsche Werkbund's famous Werkbundkiste, a chest of contemporary best case examples which was, similarly, sent on tours to explain to post-War West Germans what was, according to the post-War West German Deutsche Werkbund, tasteful, contemporary, desirable, relevant, etc...

There is something therefore very fitting about the Werkbundarchiv having recently acquired a number of original Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe graphic art exhibits, exhibits which form the core of Commercial Design instead of Applied Art?

That many of those who played a leading role in the movement away from the confusion and excess of historicism and into the more refined forms that became Art Nouveau and ultimately International Modernism were trained as artists, one thinks of the likes of Henry van de Velde, Peter Behrens or Richard Riemerschmid, a logical entry point for them to the developing field of applied arts was through two dimensional work, something particularly neatly expressed in context of Behrens through the exhibition Peter Behrens. The Practical and the Ideal @ The Kaiser Wilhelm Museum Krefeld

In addition to the, essentially, decorative book, calendar and exhibition poster design commissions, many creatives also undertook commercial commissions and, as the exhibition title neatly implies, it is examples of such commercial work that are on show in Commercial Design instead of Applied Art? Whereby we assume the "?" is a rhetorical "?" highlighting the question the artists of the period would have posed themselves, rather an invitation to decide what one is viewing. We'd argue in any case it's both. Graphic design being for us not design but applied art. Which is why we don't have many graphic designers as friends. Or indeed graphic applied artists.

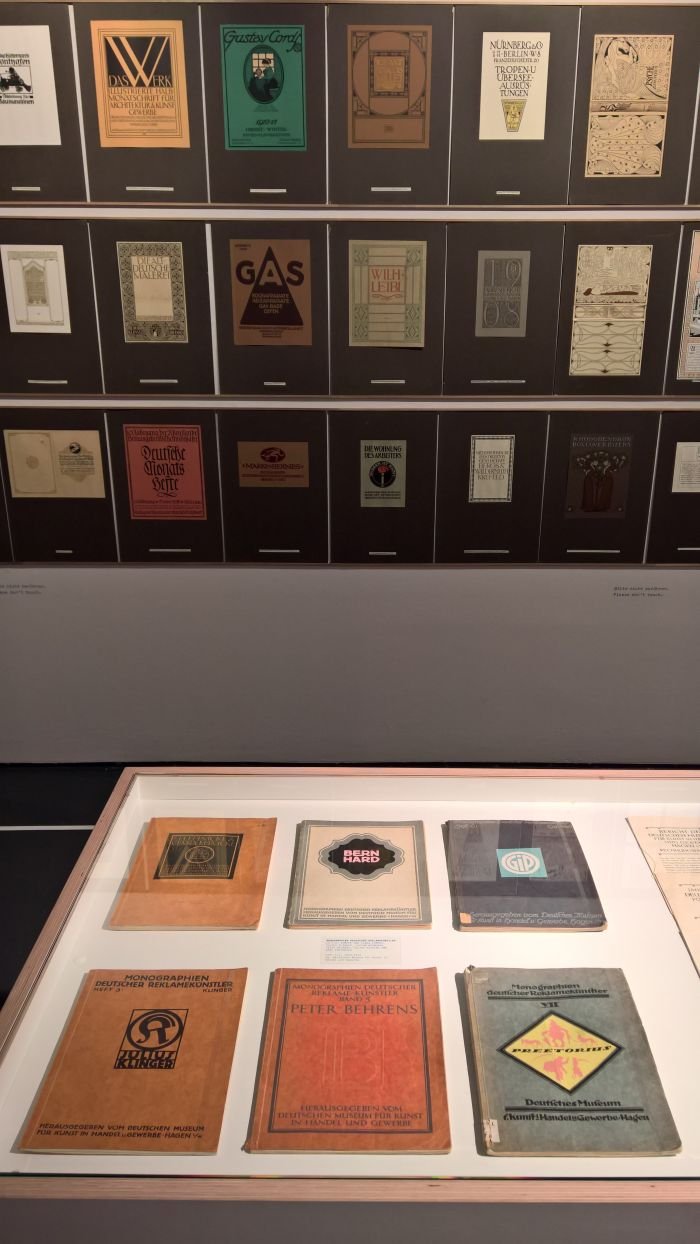

Based on the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe's exhibition Reklame und kaufmännische Drucksachen [Advertising and commercial printing], Commercial Design instead of Applied Art? presents some 120 commercial graphics ranging from letterheads and invoices over newspaper advertisements, menus, packaging and onto beer labels, specifically two Sternburg beer labels: not only interesting for the experience of Sternburg beer in an exhibition, but for being the only example in the exhibition of a before/after comparison. And thereby also highlighting that which, for us, is missing in the presentation: examples of where we had come from. There being no other examples of the sort of work Osthaus was trying to move society away from, examples of what he would have considered distasteful, outmoded, disagreeable, irrelevant, etc... Just what replaced it. And although the absence doesn't detract from the presentation, the focus being that which was being produced by reformist artists in the early 20th century: the Sternburg labels do remind us that to fully understand the works, you, and as in all areas of life, have to be aware of the history.

Featuring examples of works by a wide range of artists, including the likes of Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens, Ivo Puhonny, Johann Cissarz or Josef Hoffmann, one of a, relatively, large number of creatives from the Wiener Werkstätte, and which in its own way points to the international, networked, nature of a period in architecture and design history often considered from regional, isolated, perspectives, a particular feature is the work of the Stuttgarter Lucian Bernhard: the man responsible for the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe's corporate identity, and thereby clearly afforded heavy visibility by the institution, but whose importance is also underscored by examples of commissions for the likes of Adler, Kaffee Hag or the Frankfurt type foundry Flinsch, one of those manufacturing companies who cooperated with the creatives of the period to help them achieve their vision, and without whose contribution the (hi)story of the 20th century could have been so very different.

In addition Commercial Design instead of Applied Art? includes, albeit only to view on not in, a collection of monographs published by the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe devoted to artists such as, and amongst others, Peter Behrens, Emil Preetorius and Julius Gipkens, the latter clearly having developed his own logo, and also a small selection of the type of objects represented in the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe's exhibitions, including the obligatory Behrens AEG kettle. The presentation is very neatly and pleasingly rounded off by a small reading corner which invites visitors to delve deeper into the subject than can ever be possible in the confines of the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge's temporary exhibition space.

Partly on account of the fact that memories of Against Invisibility – Women Designers at the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau 1898 to 1938 at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden are still very fresh in our minds, and partly on account of a couple of other projects on which we're working, we currently can't view an exhibition featuring work from the late 19th/early 20th century without actively looking for female artists. Just of one of our newer ticks, and one of the few ticks we have which we recommend to all.

And one that is particularly difficult to satisfy in context of Commercial Design instead of Applied Art?

As an exhibition Commercial Design instead of Applied Art? presents the original Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe exhibits without any further comment or notation: a concept which on the one hand succinctly demonstrates how viewers a century ago would have experienced the works, something of which we highly approve; but which does, on account of the many missing labels, mean that not all the responsible artists are identified, a lot of works hanging anonymously. And some of those that are named are, potentially, incorrectly so. Or perhaps better put, insufficiently so.

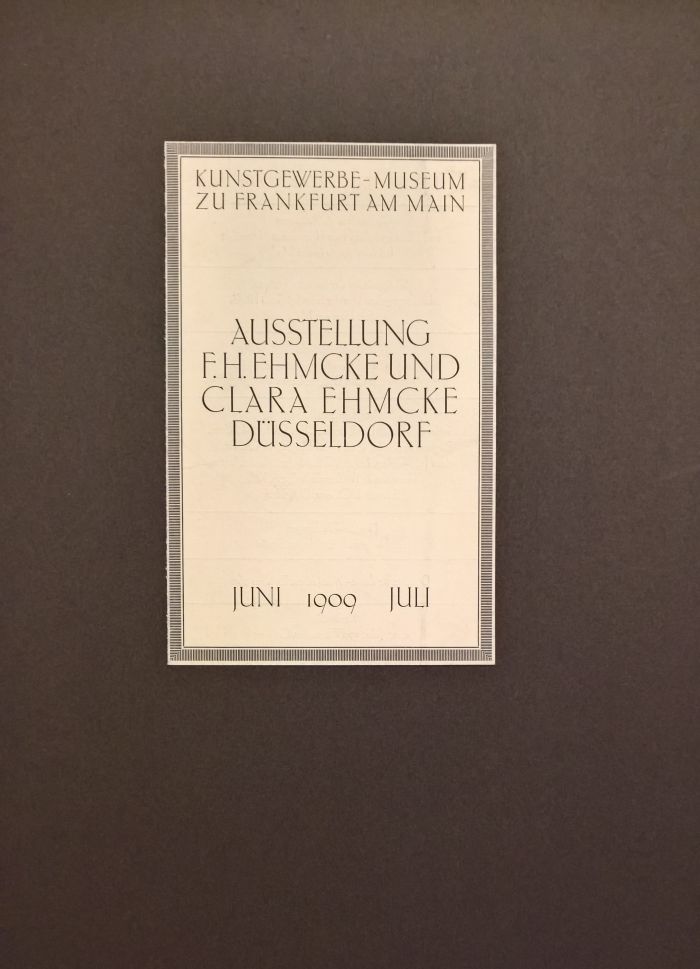

Specifically. Among the presented monographs is one devoted to the Düsseldorf based couple Fritz Helmuth & Clara Ehmcke. Works by Fritz Helmuth Ehmcke can be found amongst the presented examples. Works by Clara Ehmcke cannot. Nor works by Fritz Helmuth & Clara Ehmcke. Not even the brochure produced in context of an exhibition of Fritz Helmuth & Clara Ehmcke's work in the Kunstgewerbemuseum Frankfurt. That was done, apparently, by Fritz Helmuth alone. Which sounds implausible. May however be true. We no know.

What we do know is that Commercial Design instead of Applied Art?, and therefore by extrapolation, the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe's exhibitions, were/is not completely devoid of female artists, assuming that is "B.Kiessewetter" is, as we assume, the Austrian artist Adalberta "Berta" Kiessewetter. And so should it prove that Clara Ehmcke did contribute to any of the "F.H. Ehmcke" works on show, but isn't credited owing to decisions made by the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe, and therefore at the time denied proper recognition of her contribution to the realised works, that would be incredibly apposite: Clara Ehmcke being featured in Against Invisibility. Albeit under her maiden name of Clara Möller-Coburg. Which may also help explain part of the contemporary invisibility of late 19th/early 20th century female designers.

In no sense an exhibition purely for graphic designers, typographers and their ilk Commercial Design instead of Applied Art? provides for a very pleasing overview of the types of commercial graphic, typographic, design that was taken place in the first decades of the 20th century and, even without the (desirable) before/after comparisons, does help explain how the clarity and reduction of the graphic art of the period not only reflected, and helped support, the developing clarity and reduction of three dimensional design and architecture as society moved its way through the early 20th century, but also how that move helped drive a few more nails into the coffin of Fraktur, and therefore not only influenced modernist design vocabulary but typography and chirography.

And thereby also provides for a clear indication of the importance of both that period in paving the way for all that has led us to where we are today, but also of the Deutsche Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe in helping disseminate ideas, or perhaps better put, of more rapidly disseminating ideas and making the new ideas of the period readily available to as wide a section of the population as choose to view their exhibitions. And thereby helping prepare the ground for what Bauhaus has come to popularly represent.

Commercial Design instead of Applied Art? runs at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Oranienstraße 25, 10999 Berlin until Monday February 18th

Full details can be found at www.museumderdinge.org