Our visit to the 2018 Glasgow School of Art Degree Show occurred before the recent fire, indeed this post was all planned to go, then came news of the fire ... and it seemed appropriate to wait.

But not to archive it away altogether, for tragic and destructive as the fire unquestionably was, an art/design/architecture school is its staff and students and ideas and visions and understanding of the world. Not the bricks and mortar that surround it.

Even if those bricks and mortar were arranged by Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

And so with reflections on what has been lost, but our eyes still firmly on the future.....

Although the school itself traces its history back to 1753 and the establishment in the city of an Academy of Fine Arts by the Glasgow printers Robert and Andrew Foulis, more realistically the institution's origins can be found in the 1845 Glasgow Government School of Design, one of a number of regional design schools established by the then government to help promote the development of contemporary objects appropriate for contemporary industries. And an initiative whose legacy can be gauged from the number of UK design schools who trace their origins back to a mid-19th century Government School of Design.

Originally based in Ingram Street in the heart of the city, in 1869 the renamed Glasgow School of Art, GSA, moved to the newly constructed, neoclassic, McLellan Galleries on Sauchiehall Street before continuing its westward move in 1899 with the completion of the first stage of the new Glasgow School of Art building by Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

And a building which not only was itself important in the development of the Scottish interpretation of Art Nouveau, but which housed many of Scotland's leading Art Nouveau protagonists, thus making Glasgow School of Art one the UK's leading creative schools at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries. Whereby the role of its long term director Fra Newbery is particularly relevant and important, and arguably more so than that of Mackintosh.

Despite the somewhat unequivocal name the Government School of Design was initially very much focussed on drawing, and it wasn't until 1849 that design as such began to be taught, architecture following in 1885. Thus completing a trinity of creativity that remains the foundation of the institution.

Today Glasgow School of Art is home to some 2,000 students studying art, design and architecture in its various forms at its five schools: the Mackintosh School of Architecture, the School of Design, School of Fine Art, School of Simulation & Visualisation and since 2017 the Innovation School, home to not only the Product Design courses but also courses in, for example, Environmental, Interaction and Social Design

Staged in the school's 2014 Reid Building by Steven Holl Architects, the design section of the 2018 Glasgow School of Art Degree Show presented projects from Interaction Design, Silversmithing & Jewellery; Fashion Design, Textile Design, Communication Design, Interior Design, Product Design Engineering and Product Design graduates, whereby the take home message from latter group is that the future is Artificial Intelligence.

And an Artificial Intelligence future which not only places an illogical and irresponsible amount of faith in the infallibility of Artificial Intelligence, but also in the belief that something a computer algorithm decides is inherently better than that which a human decides; future realities we hoped were meant as deliberate provocations devised with the intention of stimulating debate. But which over the course our visit to GSA we came to realise were in fact meant seriously.

Owing to the way our #campustour is managed, we are physically much further through it than the posts imply, and Glasgow School of Art ain't an exception in its faith in Artificial Intelligence, and so we'll return to the subject of our future world in detail at a later date.

What we will add about Glasgow School of Art however is that although the students were obliged to develop an Artificial Intelligence project as part of the "Future Experiences" seminar, a seminar which asked the students to consider "the notion of human work in the twenty-first century, if what we do is no longer measured in terms of efficiency, replication and productivity"; the overwhelming majority of the projects involved some form of necessary, self-evident, unquestioning, computer interface to guide/aid/assist/promote human activity and interchange. Which confuses us. But as we say, more later.

Elsewhere we spent a disproportionately long amount of time viewing the Product Design Engineering, PDE, projects, Established in 1991 PDE is a joint programme run by Glasgow School of Art and Glasgow University's School of Engineering, and thus combines the form-giving and problem solving of the designer with the cold calculating efficiency of the engineer, and thus represents an interesting example of inter-disciplinary design studies. The length of time we spent viewing the projects not being because we didn't understand them, but because they covered some very interesting topics and produced some interesting solutions including, Bitesized by Natalie Fuller, essentially a pair of scissors designed to assist those with the use of only one arm cut up food while dining; Eddy Kettle by Kevin O'Malley, a technologically reduced kettle which re-imagines/questions what a kettle can or should be; and Rapid Garment Ironing by Zeyu Ren which in effect is a 21st century trouser press.

Elsewhere, and in no particular order.......

Tragic as it may seem, but if we keep on as we're going, which we are hopefully not going to, but then again, humans!!!, plastic waste in the seas could mean a reduction in income from fishing for coastal communities. Jonas Gentle uses the phrase "post-fish economy". Which makes us laugh. Even though we know it shouldn't. Currently there are numerous projects exploring how we can best remove plastic waste from the oceans, until that is we stop putting it there in the first place; Plastic Oceans by Jonas Gentle focusses less on the "how" and more on the next step, the "what do we do with the plastic?", and proposes that those communities most affected get first dibs on the plastic. A plastic that is, lest we forget, a resource.

Which seems only fair.

As presented at the GSA exhibition it proposed coastal communities moulding the harvested plastic into plastic fish; plastic fish which are not only symbolic of the real fish they've replaced, but which, and much like the ingots of raw metal with which industrial production began, can be melted down and used as the basis for new objects.

Much as we liked the imagery, we were much more taken with the considerations on coastal communities having control of the harvested plastic waste and the choice of either using it themselves as the basis of new local industries, or selling it on. Which, as we say, seems only fair.

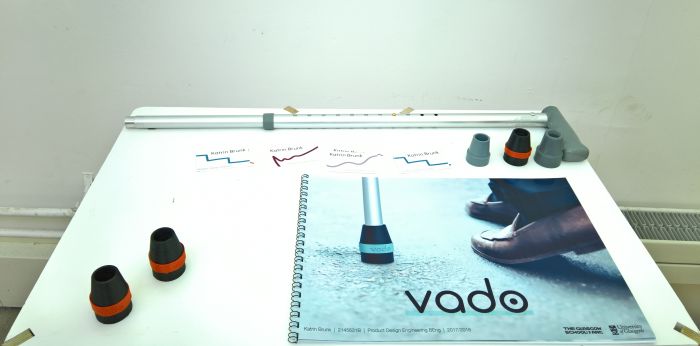

There is something eminently logical about Vado, so much so it seems almost impolite to mention it, but......

Essentially Vado proposes integrating a monitoring device into the end of a walking stick which records the users movement date. Not in a way that Californian tech conglomerates monitor movement data, but in a way that means a physiotherapist can subsequently analyse the data and use it, in conjunction with other, physical, assessments, to help optimise the patient's treatment.

While so-called gait monitoring devices aren't new they are generally based on insoles, and thus, and for all in context of elderly patients, introduce an extra level of complication, and cost, into the daily routine. A system integrated into a walking stick is not only unobtrusive but also, we would imagine, cheaper and easier to maintain and manage. The most important element is that the data it delivers is relevant for the physiotherapist, which we have to assume Katrin has assured it is.

Although the benefits of Spirulina as a supplement to a healthy, balanced diet may not be proven, the value of Spirulina as a food stuff itself, and for all its potential as a nutritional, protein rich component of any post-agrarian future, is much better resolved.

With Lina Jessica Thomasson proposes a system for home Spirulina production.

Now in these pages we've oft commented on the implausibility of many of the "home farming" systems we've been confronted with; appealing, even logical, as they may be, people ain't going to use them. Not on a large scale. Or at least not yet, not before they are forced to by the collapse of the global food industry.

Lina strikes us as being much more plausible.

Although presented as a model in Glasgow, and presumably still with a good deal of development work ahead of it, the simplicity, efficiency and economy with which Spirulina can be produced, the fact it glows with a pleasing green as it does, and the multitude of uses it can be put to in the contemporary kitchen, tends to imply success.

And all who buy one will not only be able to (questionably) enhance their smoothies, but be prepared for the coming apocalypse.

As e-mobility increases so to does the question of provision of charging points for electric vehicles. Static charging points, be they integrated into existing buildings/objects or as a new form of stand alone urban furniture, are a logical solution; but do come with the problem that the car has to be at the charger. And then moved away from the charger so that others can charge.

Addressing such issues Sweden has recently opened its first test section of road which charges moving cars; a much more satisfying idea, but one which while conceivable in motorways and other long distance highways is unlikely to be suitable for urban spaces. Involving as it does a massive infrastructure intervention that most communities are likely to shy away from.

Incharge offers an alternative. In the proposal presented in Glasgow it imagines an induction charging pad on a rail-esque system sited under the road. You park your car over the rail, book a charging session and when its your time the pad moves under your car and charges it. Before sliding off to the next car. Taken directly as presented it could, for example, charge up a street of cars overnight.

A very appealing idea and one that while very intensive in terms of retro-fitting existing streets, can be effortlessly integrated into new streets/estates.

Alternatively one could conceivably integrate such a system into a car park, and where over the course of a working/shopping day several pads charge up the cars, and thereby providing an additional service for customers/employees.

Quite aside from the technical questions, and we imagine there are still a great many to be solved, the key question is going to be the financial/economic one, but certainly questions it would appear are well worth exploring.

As with the Homebase Furniture by Malmö University graduate Nora Buerhop as seen at the 2018 Vårutställning at the Form/Design Center, Malmö, what caught our attention with Sofa for Life by Saskia Göres was less the actual object created and much more the system thinking behind it.

As Saskia notes, among the reasons that people dispose of sofas is that they can be difficult to clean, repairing is often more expensive than replacing, and when you move the old sofa might not be so optimal for the new space. The result is a lot of dumped sofas i.e. waste.

With Sofa for Life Saskia proposes taking the familiar, and ever sensible, modular concept and placing it in a new, circular, production and distribution system; one where you configure your sofa online, it comes delivered in a convenient flat pack system which you assemble, tool-free, and then as you move through life, with all its planned and unplanned twists and turns, you can exchange, expand, reduce, remodel, your sofa as required, and even transform it into, for example, an armchair or a bed.

Important in and to the system is that no longer required, useable, components are returned to the manufacturer, put back into circulation and thus made available to other users; no longer required, unusable, components are returned to the manufacturer, recycled and used in the production of new components for the system.

As noted before, although modular furniture has been around for many a decade, all to often users create an object and so it remains in perpetuum, modular sofas being a very good example. By reducing her sofa down to a series of simple, clear components Saskia allows for the necessary differentiated perspective on the concept. And thus the possibility for better use of the wonders of modularity.

Full details on Glasgow School of Art can be found at www.gsa.ac.uk

Details on the 2018 (and 2017) Product Design Engineering graduation projects can be found at www.pdedegreeshow.com

Details on the 2018 Product Design projects can be found at www.flickr.com/glasgowschoolart