"We are children of the age of the steam engine, the telegraph and electricity. We have turned our backs on the beautiful, and that is why we no longer understand it", bemoaned the Dutch draughtsman, designer and educator Johannes Ros in his 1904 text "Het doel" [The goal/target/objective]

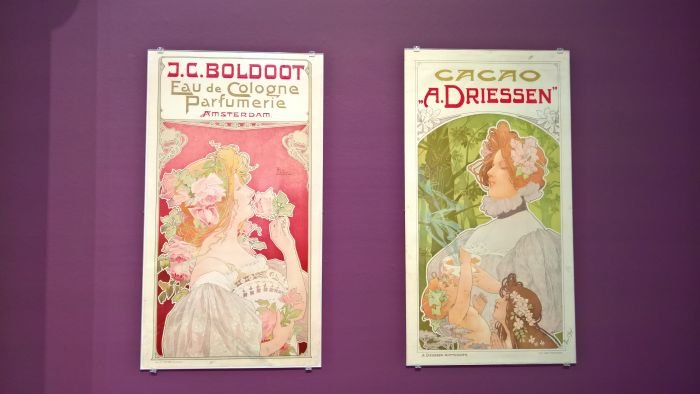

How Johannes Ros and his contemporaries attempted a return to the beautiful, indeed what was understood as beautiful in the Netherlands at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, and for all the particular Dutch accent of that attempt/understanding is explored in the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag's exhibition Art Nouveau in Nederland.

Although superficially Art Nouveau can be, and all too often is, considered an artistic style, it was much more a reaction to evolving technical, economic, social and cultural realities.

By the second half of the 19th century the European population was growing rapidly, for all urban populations; political structures were being reconfigured, established systems of power openly challenged; new freedoms were being demanded and granted, for all through the abolition of slavery and increased female emancipation; personal wealth was growing, or at least was amongst a privileged upper layer, lower down poverty and slums prevailed, creating its own social tensions; industrialisation was become ever more established and developed, stimulating in its wake a discussion about form and aesthetics when machines make objects rather than carpenters, metalsmiths, potters, et al. Or indeed, if they should even be allowed to.

The responses of the leading protagonists of Art Nouveau were as varied as the nature of the changes of the period; some, for example, were looking to shake of the shackles of the past with new objects and new formal expressions which reflected the spirit of the age and its social and cultural revolutions; others sought to maintain not only associations with the familiar, established formal understandings, but also with the traditional, established nature of their production; while yet others were interested in objects created with the aim of aiding their industrial production, objects which, in many regards, would be deemed attractive precisely because they were off the new steam engine/telegraph/electricity age; we could go on......

As an exhibition Art Nouveau in Nederland makes clear that while Dutch Art Nouveau shared many motivations, characteristics and traits with its counterparts elsewhere, it did have its own peculiarities.

Peculiarities that were largely a consequence of the domestic and international realities of the period, peculiarities which bequeathed Dutch Art Nouveau an individual character, and peculiarities that are apparent from the very beginning of the exhibition.

As industrialisation and urbanisation grew so too did an interest among creatives in the natural world, as a, if you will, reaction to the loss of nature being felt elsewhere, and a reaction which is arguably one of the reasons for the prevalence of natural motives in Art Nouveau art and applied art. For all floral motives, motives, invariably, present in Art Nouveau in Nederland, yet, which, and as with the examples of Danish design from the late 19th century presented in the Grassi Museum Leipzig's exhibition Design in Denmark since 1900, are much more of the realistic, naturalistic type than the abstract, figurative works associated with Art Nouveau in, for example, Germany, Belgium or Scotland.

The relevance of this realistic, naturalistic representation isn't made immediately clear by the exhibition, arrives however a couple of rooms later, and so, following the exhibition's lead, we too shall make you wait.

Beyond florid fascinations Art Nouveau in Nederland also highlights Dutch affections with other natural forms, for all avian motifs, and particularly the peacock, arguably a bird perfectly suited to decorative purposes, one that crops up in works from other nations, but one for which the Dutch obviously had a particular fascination, peacocks cropping up both figuratively and naturalistically, throughout the period presented by Art Nouveau in Nederland and across works by the numerous, often antagonistic, protagonists. Thus making the peacock, as one learns to appreciate through the course of the exhibition, one of the few uniting concepts in a period of artistic friction.

The first reference to that other Art Nouveau staple, Japan, is also natural, specifically piscine, and as represented through a series of aquatic motifs, including porcelain works which repeat the realistic, naturalistic motifs of the floral artists and in paintings by Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof, which although featuring essentially romanticised representations of fish are far removed from the more abstract, figurative representations found in Japanese art. The species also differ, whereas the Japanese focussed on the koi, Dijsselhof portrays much more mundane, Dutch, species, such as bream or pike.

The parallels however are clear, as are the Japanese influence.

As previously discussed, the opening of Japan in the mid-19th century following 250-ish years of self-imposed isolation exposed 19th century Europe to all manner of new exotic impulses; impulses which played a key role in the development of Art Nouveau, for all in terms of formal aesthetics, but also in terms of, for example, construction methods or materials.

In context of Dutch Art Nouveau a further important, Eastern, impetus was the colony of the Dutch East Indies and for all batik, a wax based textile dying technique originating in the islands, particularly the contemporary Java.

Initially championed by the likes of Carl Lion Cachet, Johan Thorn Prikker or Chris Lebeau, batik became particularly important in context of the works of Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein whose batiks not only helped give Dutch Art Nouveau a character and feel very different from that elsewhere, but was also one of the few international successes of Dutch Art Nouveau. Arguably because of their novelty. Because of their allure of the exotic.

Even if, or perhaps better put, because, that allure was largely based on highly romanticised, idealised European understandings of the "orient", understandings which not only ignored the injustices of colonial rule, but also the reality of everyday life for the domestic population.

And romanticised, idealised imagery which, and to bring us back to the flowers with which the exhibition opens, complimented the realistic, naturalistic, impressions of nature, to help amplify notions of Dutch nationhood, were a way of confirming a romantic national Dutch image: and that at a period in history when the fluid political situation in the Europe arguably increased a longing for a confirmation of the term "Dutch". While overseas the Boer Wars were raging in the contemporary South Africa, and while not directly involved, many in the Netherlands had a great empathy and sympathy with the Boer, and parallel an animosity to the British Empire, and thereby an increased sense of Dutch nationalism and a heightened receptivity to concepts of a Dutch identity.

And a situation which in terms of its influence on design and the decorative arts is perhaps best explained through the institution of the gallery/shop/manufacturer Arts and Crafts in Den Haag.

Established in 1898 by John Uiterwijk and Chris Wegerif, Arts and Crafts took its name from the British movement and many of its inspirations from Liberty of London, one of the leading commercial protagonists of Arts and Crafts; its business model however was very much based on that of the Art Nouveau retailer, Siegfried Bing's Maison de l'Art Nouveau in Paris.

In addition to presenting works from Dutch artists, for all Johan Thorn Prikker, Chris Wegerif himself and his wife, the aforementioned, Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein, Arts and Crafts also featured works by international artists, perhaps most notably Henry Van de Velde who designed a bedroom and dinning room for the gallery's opening exhibition.

And this international perspective, the association with Bing, the association with the English "adversary", but for all the association with the person of Van de Velde and his penchant for flowing, figurative lines, brought with it much criticism and animosity. Or as the designer and critic Hendrik Willem Mol is quoted as exclaiming "God preserve the Flemish and us from the influence of Van de Velde's work".

The principle objection to Van de Velde, and for all to what the architect and designer Karel Sluijterman, disparagingly, if absolutely deliciously, referred to as "modern Belgian curvatures" was that they were considered unDutch, that they lacked not only a modesty and sobriety considered inherent to the Dutch character, but that they lacked an authenticity.

The counterweight to Arts and Crafts was found in the Amsterdam based manufacturer/retailer 't Binnenhuis, established in 1900 by Hendrik Berlage, Jacob von Bosch and Willem Hoeker, and whose focus was much more objects based on established Dutch typologies, and for all on objects which reflected perceived Dutch attributes, attributes exquisitely described by the writer and publisher Leo Simons as "honest and sincere and ruggedly sturdy".

Whereby the form of much of the language used should set several alarm bells ringing; the use of such rudimentary, provocative, symbolic, emotional, language, and for all the establishment of associations with ideas of a national identity, tending to indicate critics with an agenda, critics who are looking to forcefully lead a discussion in a certain direction, and potentially obfuscate their own shortcomings. And that the motivations may have been primarily about promoting their own interests.....

Suspicions strengthened through viewing the objects presented in Art Nouveau in Nederland where one finds many similar themes in the work from both camps, for all the depiction and representation of animals and plants, but also the visual lightness of the objects in comparison to similar objects from previous centuries, even if the examples of 't Binnenhuis furniture on show in Den Haag don't match the visual reduction with the material reduction expressed by the Arts and Crafts objects. And although in terms of the construction both employ very simple techniques and joints, the 't Binnenhuis objects tending to emphasise the joints more than the Arts and Crafts works, relying more on the amount of material employed, and their rugged sturdiness, for their expression. The Arts and Crafts works in contrast expressing themselves much more through their form.

Forms which 't Binnenhuis co-founder Berlage denounced as presenting, "all kinds of useless lumps of wood in the most tasteless combinations of lines have been hung on or applied to the furniture, which themselves have impossible shapes, entirely useless, crooked, lopsided and bent."

A criticism whose poetic brutality caused us to laugh so hard we choked. And still brings a smile to our faces. And which tends to underscore that the venom against the international decorative style and promotion of an idea of an authentic, rugged, Dutch style was more about marketing than art theory.

Beyond the development of Art Nouveau in the Netherlands per se, the exhibition also makes a couple of all too brief detours, the one exploring the role of female creatives, such as, and amongst many others, Johanna van Eybergen, Gerarda de Lang, Bertha Bake or Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein, in the development of Dutch Art Nouveau, whereby particularly pleasingly is that it doesn't feel as if it is has been crowbarred into the presentation, doesn't feel programmatic or preachy but is, and feels like, a natural focus. One which doesn't seek to redress a perceived imbalance, but more make the unthinking visitor aware that, yes, female creatives were active, were important, were relevant. And that despite the very obvious challenges they faced in a still essentially patriarchal society.

The second detour explores the reforms of the Dutch artistic education system which accompanied the technical, aesthetic and functional reforms of the period, and specifically a focus on what the curators refer to as the Leer van het Ornament, the "Theory of Ornament", a theory that spoke in favour of keeping ornamentation on flat surfaces flat and not adding a unnecessary third dimensions, or if you prefer, keeping ornamentation simple and appropriate to the object rather than using it to aggrandise an object, to introduce a level of complication simply for the sake of it. And, thereby, one could argue, to keep ornamentation Dutch.

Guess what we'll be keeping an eye out for on the Dutch leg of our 2018 #campustour.......

Presenting some 350 objects divided across 13 bite size chapters Art Nouveau in Nederland is an open and accessible exhibition which makes intelligent use of short texts to not only explain the (hi)story of Art Nouveau in the Netherlands, but to encourage, demand, expect, further consideration and reflection from the visitor.

Yes, and as with all such exhibitions, Art Nouveau in Nederland is a lot of items in glass vitrines, chairs on pedestals and similar unsatisfying display methods; however, the dynamic of the narrative, and the intuitive integration of the architecture of the Gemeentemuseum into the exhibition design to create natural sub-divisions and regular changing thematic fields make each of the, often very small rooms, appear like a fresh start and so you don't get the impression of a lot of object in glass vitrines or chairs on pedestals. While the outrageous display cabinet by Johannes Lorrie in the middle of the exhibition makes you long for more such vitrines.

Which only leaves one question unanswered, the legacy of Dutch Art Nouveau. Whereas, and at the risk of oversimplifying to the point of falsehood, in other countries one can trace a line from Art Nouveau over an avant-garde and onto international modernism, and thereby from Art Nouveau to industrial production, in the Netherlands that line is a lot less clearly defined. Many of the leading Art Nouveau protagonists retaining their preference for the more traditional and amalgamating into the so-called Amsterdam School, an understanding of architecture and design to which De Stijl was in many regards a reaction.

Or put another way, as the final wall text in the exhibition freely admits, Dutch Art Nouveau "proved to be an inadequate response to the modern age", and in many regards the relevance of Dutch Art Nouveau can be ascertained by the number of its protagonists who remain in popular international memory. But which we mean the relative lack of.

Which isn't to denigrate or otherwise belittle what Dutch creatives were achieving in the decades around the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, Far from it. The debate that raged in Holland about the direction of construction, form, ornamentation; the role of nationalism in considerations of formal aesthetic questions; the contradictions inherent in the use of both romanticised, idealised and also naturalistic, realistic imagery; the workshops established and craft focus of many of the producers; the prominence of female creatives; even (primarily?) the subsequent irrelevance into which Dutch Art Nouveau fell, all being important in helping us arrive at a fuller understanding of Art Nouveau and its contemporary relevance.

And for all in helping us arrive at an understanding that Art Nouveau isn't and never was a "style" but a reaction to "the age of the steam engine, the telegraph and electricity"

Art Nouveau in Nederland runs at Gemeentemuseum, Stadhouderslaan 41, 2517 HV Den Haag until Sunday October 28th

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.gemeentemuseum.nl