While others spend their summers' holidaying with families, barbecuing with friends or pretending to read novels on the balcony, at the beach and/or in the local park, we travel Europe visiting design school summer exhibitions and subsisting exclusively from falafel. It's a curious, idiosyncratic, slightly tragic, way to spend your life, but it's the one we've chosen, is in many regards the only road we've ever known. And so, as May's warmth ceded to the heat of June, we made like Whitesnake.... Here We Go Again.

Our 2018 #campustour kicked off in Stockholm, a city as closely related with the Hanseatic League as smow, and specifically at Konstfack, Sweden's largest and oldest art/craft/design school.

Established in 1844 as the quaintly titled Söndagsritskola för hantverkare (Sunday Drawing School for Artisans/Craftsmen) the institution was taken under the tutelage of the Swedish Association of Handicrafts in 1845 and was raised to a national school in 1859. In 1879 the artisans were joined by civil and mechanical engineers with the creation of Stockholm Technical School, and thus the institute remained until the end of the Second World War.

In 1945 Konstfack not only acquired its current name but began to take on its contemporary form, separated itself from the, purely, technical, engineering disciplines, returned to its more craft/art origins and today offers Bachelor courses in Graphic Design & Illustration, Industrial Design, Interior Architecture & Furniture Design, Ceramics & Glass, Fine Art, Textiles & Ädellab - interface jewellery/body - and Masters in Craft, Design, Fine Art, Visual Communication and Visual Arts Education.

Given its history and status it should come as no surprise that Konstfack counts some of Sweden's most celebrated creatives amongst its alumni including, and amongst many others, Stig Lindberg, Carl Milles, Vivianna Torun Bülow-Hübe, Gunnar Asplund, Wilhelm Kåge, Åke Axelsson, Jonas Bohlin, Mats Theselius and Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto, Ola Rune a.k.a Claesson Koivisto Rune.

The 2018 Konstfack Degree Exhibition offered the coming generation a chance to pitch their first claim to join such a list.

We're not saying there is a lot of anger and discontent in contemporary Sweden, are saying that strolling round the 2018 Konstfack Degree Exhibition one was regularly confronted by projects tackling questions of gender equality, female emancipation, misogyny, existential imperatives and contemporary society's (highly questionable) values. And every so often caught a glimpse of the posters announcing "Fear no longer exists": only those who fear can be suppressed.

Amongst such social query it was perhaps inevitable that a couple of projects concerned themselves with religious questions: Simeon Goodwin proposing in place of existing scriptures, the "Topical Testament", a movement based on chance “because Chance delivers good and ill fortune to all, it is indeed the overarching deity which controls life"; and Francesco Fiammenghi who considered the effects ever falling numbers of practising Catholics could have not only on the church as an institution, but also the church as a building, as part of the urban fabric. Francesco's solution being mobile inflatable churches which would allow for a more nomadic based institution and thus an emphasis on "the humanity and missionary future of Catholicism." We'd argue for just calling it a day, for accepting you'd had a good run, but time was up. But as ever, what do we know?

Elsewhere, and in no particular order, the following projects got us thinking......

In his book Design for the Real World Victor Papanek suggests that designers should work ten percent of their time for social/environmental projects rather than designing for companies/profit. Individual Cups by Annelie Hultman presents just the sort of project, we suspect, Victor Papanek had in mind.

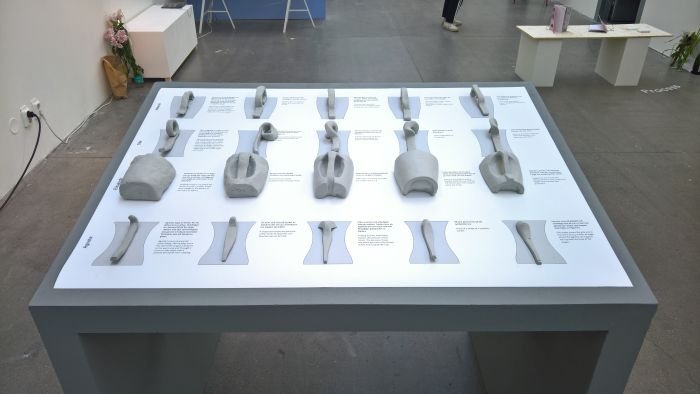

Exploring the application of 3D printing technology to create cup handles specifically adapted to the needs of those who through a range of medical conditions don't enjoy full mobility in their hands, the project very neatly demonstrates that while there is justifiably a lot of talk as to how technologies such as 3D printing can/will revolutionise industrial production, the same technology, the same thinking, can be employed to create meaningful solutions at the individual level, at the social level, and therefore making such technology just as important and relevant for society as commerce.

And which to come back to Victor Papanek: what if once a month, or however appropriate, a designer goes to a care home, old folks home, hospice, other institution where they can assist, or indeed links up with staff in some institution in a far off land, and develops not only cups with personalised handles, but crockery, cutlery, door handles, remote controls, dog leads, whatever is needed. 3D printing technology and contemporary materials make such not only possible, relatively, straight forward and cost effective, but supremely logical and in many regards obligatory for any society daring to call itself civil. Not least on account of the continual adaptability: should an individual's needs change the handles can be adapted, re-printed and, ideally, attached to an existing cup/knife/door/dog lead/whatever.

Although conceived for use in context of job interviews, for us that is too narrow a sphere of use, for us Johan Lantz's project has a potential value in all manner of conversation/meeting scenarios.

Taking the metaphoric "elephant in the room" Johan forces the protagonists to, literally, grasp the elephant, containing as it does the stools and fold-out table required for the meeting, while a series of small blackboards which together form the silhouette of an elephant - an object resemblant of those meat cuts diagrams that hang in butchers shops and faux-industrial gastropubs - serve as the basis for guiding the conversation....in Johan's job interview scenario the blackboards contain the key areas/subjects of interest to the interviewer, the interviewee's answers then build up to form the final result, much as in the proverb of the Blind men and an elephant, their individual interpretations of the one part of the elephant they can touch joining to form the whole elephant.

But as we say, for us it needn't just be for job interviews, but any face-to-face conversation that could, potentially, possibly, be a bit awkward or unpleasant, where bringing a bit of informality in at the beginning could be helpful in defusing any later tensions, and that not just in professional situations but also in social situations, educational establishments, hospitals, etc, etc, etc

Yes, if you were exposed to the elephant on regular basis its effect would become diluted over time, you'd get to know the trick, but otherwise a very interesting proposal.

Explorations of imperfection in objects are a recurring theme in design school projects, and well suited to such, forcing as they do both the student and the observer to question their understandings of form, aesthetics, "correctness"

Approaching Teemu's chairs, and before we'd read about the project, we decided we were quite taken by them. Were more sceptical about the stool and the side table.

After we'd read about the project, discovered it was concerned with imperfection, we searched for, and found, some of the imperfections Teemu had deliberately built into the objects, but not all; Teemu pointing the rest out to us.

Having become acquainted with them, and understanding how obvious they actually were - the asymmetrical heights of the extensions of the chair's back legs, for example, the non-alignment of the wood grain on the chair's backrest or the unaligned legs on the side table - we naturally began to question in how far we are actually suited to do what we do if we can't spot such. Before quickly moving on to reflect that much as when reading or listening we all tend to fill in information gaps, blend out that which occurs to us as nonsensical or incomplete, and replace it with that which appears logical, so to when looking at objects: when assessing the form of an object we see what we expect to see not that which is front of us. To a degree, obviously, above a certain degree of imperfection it is becomes unmissable.

Our major issue with the project is the question if imperfection would or could lead to an emotional connection? Such surely comes through use, through familiarity and the relationship one develops with an object over an extended time period. Assessing such however really requires a control set of chairs without the inbuilt imperfections. And a long range experiment

The one "imperfection" that arguably did make a difference, and which may explain our initial attraction to the chairs, is the proportions used. Since the days of Vitruvius architects and designers have concerned themselves with the proportions of the human body. Teemu Perttunen concerned himself with the proportions of the human baby body: shorter and wider than adult humans, apparently.

It may have been unfamiliar proportions for furniture, but arguably still proportions we were able to understand.

Thereby making his chairs are y very nice example of what can happen when designers lay convention to one side and approach challenges from a different perspective or with a different mindset.

3D printing with wood/lignin based materials isn't new, is however currently reserved for smaller scale, decorative objects; with his graduation project Hannes Tennberg explored taking it further, using industrial scale robots, and proposes the use of 3D printed wooden objects in architecture and construction.

In these pages we've often bemoaned that construction is still so labour intensive, so analogue, has barely progressed as industrialisation has taken a grip on neigh on everything else. New technology offers new possibilities for more automated construction, of which 3D printing with wood is a particularly interesting one, allowing as it does for the creation of buildings with a much softer/warmer character than those from 3D printed synthetics or concrete.

While beyond buildings, industrial scale 3D printed wood offers all manner of possibilities in terms or urban furniture and utensils, clearly not a catch all, universal concept but one which could not only allow for new forms of urban furniture, but also reduce costs and thereby promote greater use of more intelligently designed and conceived objects.

The objects Hannes displayed at Konstfack indicated that the concept still has a long way to go before it can be employed, however as an idea it would appear to one well worth pursuing.

"Is it", asks Johan Krantz, "time to reverse our notion, of not what is possible and what isn't, but to accept the impossibility of omnipotent immortality?"

Do our attempts to avoid death cause us to lose focus on life? Would we be less stressed, more content, if we accepted as Malcolm Middleton delicately reminds us "there's a when not an if inside everybody"?

And how far are we prepared to go to extend our lives? As new medical technology makes ever more possible how much will society embrace? How often do you measure your vital signs, your movement, water consumption? How many implants, or digital prosthetics, will you have to help you live longer? And what do you gain thereby?

And not only do we try, desperately, to extend our physical time on the planet, but we also attempt, with equal desperation, to keep the world around us as it is. For us realities such as Brexit, Trump and the rise of nationalism in Europe can be partly explained in people's fear of change, in a desperate desire to keep things as they are, because that is what one understands, the new is too uncertain, and therefore dangerous, letting it happen being a betrayal of some perceived identity and natural law. But that's not how things work. Things change, evolve, develop, continually, always have, always will. "Idealizing a distant reality holding on to the idea that this civilization can be saved is counterproductive", opines Johan, and we'd certainly argue in favour of embracing the new, albeit with critical, constructive, open questioning, rather than fighting change. Or indeed mortality.

By way of expressing himself Johan presented a life support system for Solidago canadensis, Canadian goldenrod, a highly adaptive plant that doesn't need a life support system, but did/does need the evolution of human society to help it spread globally.

One could, alternatively, have asked if Hindus are happier than non-Hindus. Even if that would involve a major simplification of the Hindu faith. But isn't that what the 21st century is all about. Simplification. And the self-delusion that allows.

Full details on Konstfack can be found at www.konstfack.se

And all 2018 Konstfack graduation projects are online at www.konstfack2018.se