1918 was a bad year for the Wiener Moderne, losing as it did with the deaths of Koloman Moser, Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt and Otto Wagner four of its leading protagonists.

To mark the centenary, and help underscore the important role Vienna played at the turn of the 19th/20th century in the development of art, architecture, music and literature, museums across Vienna are staging a wide range of specially themed exhibitions throughout 2018; the Hofmobiliendepot - Imperial Furniture Museum - taking the opportunity to celebrate not only Otto Wagner, but his younger contemporaries Josef Hoffmann and Adolf Loos.

As the 19th century neared its end, so to do did the accepted political, economic, religious and social conventions in Europe; and as so often, the greater the uncertainty, the greater the artistic productivity. In Vienna this manifested itself as the so-called Wiener Moderne, a period between, approximately, 1890 until 1910, and one which saw artists from across genres seeking with vigour and passion to transport the mood of the period into new forms of expression, to approach answers to all-pervading social, political and cultural questions and propose solutions for the brave new world that was approaching. Perhaps the most famous manifestation of the period is the Wiener Secession which provided a platform for progressive artists, but parallel, and more often than not intertwined, the Viennese coffee house became the centre of the city's literary world, musicians such as Arnold Schönberg or Alexander von Zemlinsky proposed new understandings of music, while in architecture and interiors it was also very much a case of new ideas and new approaches for the new age.

Three of, arguably the three, leading protagonists of architecture and furniture design in the period of the Wiener Moderne were Otto Wagner, that Grand Doyen of Austrian architecture and urban planning, who's Postsparkasse building set new construction, material and aesthetic standards and who's bridges and stations for the Stadtbahn urban railway network continue to enrich the individual atmosphere of the Austrian capital; Josef Hoffmann, co-founder of the aforementioned Wiener Secession, co-founder of both the German and Austrian Werkbunds and co-founder of the Wiener Werkstätte via which art and craft were unified with the aim of creating aesthetically pleasing, practical goods for everyday use, and which today is for many the principle understanding of Wiener Moderne design; and Adolf Loos arguably best known as an author and critic, his polemic "Ornament and Crime" being one of the most widely, and most widely incorrectly, quoted design theory texts, but who with his office block for Goldman & Salatsch, a building without external window decoration, and that next to the ornately festooned Hofburg Palace, created not only a work truly revolutionary of its time, but a work that remains one of the most idiosyncratic and charming in Vienna.

As the title implies Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos and Viennese Modernist Furniture Design. Artists, Patrons, Producers sidesteps the trios wider oeuvres' and concerns itself alone with their furniture designs in context of Wiener Moderne.

By way of a curatorial scene setting Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos opens with a brief overview of both the nature of architecture and design, as well as of the wider social, economic and political reality in Vienna at the end of the 19th century, including the establishment in 1863 of the Österreiches Museum für Angewandte Kunst, the contemporary Museum für Angewandte Kunst, and in 1867 of the Vienna Arts and Crafts School, institutions which helped propagate and proliferate the new ideas of the period; the rapid growth of Vienna in the second half of the 19th century, and not only the increasing prosperity of many of its inhabitants, but shifting class structures and political affiliations; but for all the importance and significance of the construction of the Ringstrasse, that broad boulevard built in the 1860s as a replacement for the old city walls and which with its magnificence of public buildings, hotels and apartment blocks not only signified Vienna's importance and gave it the space and freedom to expand, but in its imperialistic historicism also provided the impetus, the motivation, for a new generation of architects and designers who saw in the Ringstrasse a symbol of the past, a symbol they wanted to answer with something new, something which more appropriately represented the modern age.

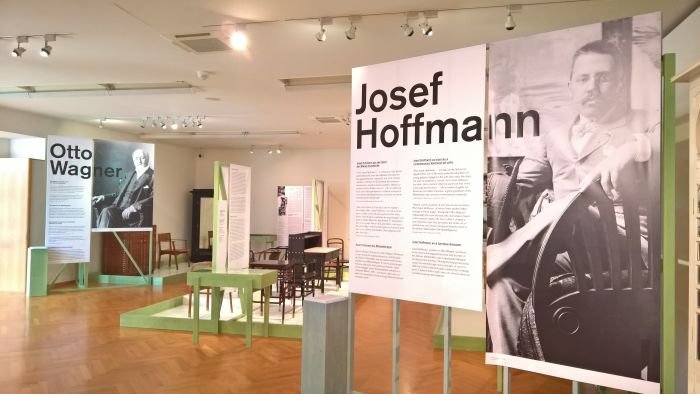

Having set the scene the exhibition moves sprightly on to its title subject. Much as the Konstakademien Stockholm's exhibition INSIDE architecture by Åke Axelsson, Jonas Bohlin, Mats Theselius gave each protagonist their own room, so Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos gives each of the trio their own space; space which is used to present three, more or less, chronological journeys which neatly and concisely explain how each developed their understanding of furniture design, or perhaps better put, how each discovered a self-confidence in their own position, a self-confidence which allowed for the development of their understanding of furniture design, formally, socially and functionally.

As each of the three (principally) created their furniture designs in context of interior design/architecture projects, it is particularly pleasing that the curators and exhibition designers have chosen to present the works (largely) as ensembles, thereby allowing the visitor to understand them as components of a wider position rather than as individual objects, and therefore allowing for a more informed impression of the designers' intentions and the competence with which that was realised.

The first designer one meets is, logically, Otto Wagner, logically not only because he is a generation older than the the other two, nor not only because his appointment in 1894 as a Professor at the Vienna Arts and Crafts school marks an important moment in the advancement of the new thinking of the period, but also because he was, when not always directly, an important influence on Loos and Hoffmann. Presenting both well known Wagner commissions from the period such as the chairs and stools he designed for Die Zeit newspaper or his Postsparkasse building, and also furniture created principally for his own use, including that for his studio in Vienna's Hüttelbergstrasse and his apartment in his Köstlergasse building, the presentation helps explain not only an architect/designer who valued the artistic, who had learned his trade in the days of historicism and who despite his rejection of it was still influenced by it, but also one who was one of the first to transfer the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk into architecture and thereby to understand his furniture as part of a unified composition rather than simply as a chair in a room.

Following Wagner, physically in the exhibition and spiritually in early 20th century Vienna, is his pupil Josef Hoffmann, an architect and designer whom one can very neatly follow as he develops from the floral geometry of Jugendstil towards a more functional and rational position: the florid lines of the bedroom furniture he designed for Ernst Stöhr in 1898, for example, standing not only in the exhibition space diametrically to the much more linear quadratic 1907 sales office furniture for the Imperial-Royal court and state printers, but also in their character, construction and raison d'etre. Whereby it is important to stress that in such an exhibition one can only present representations of a designers' canon, creative developments are by their nature rarely linear but tend to the helical; however in the Hoffmann progression his changing ideas and evolving understandings of furniture and interior design can be clearly seen, followed and understood. As can the fact that despite the ubiquity of his 1905 "Sitting Machine" in any discussion on Josef Hoffmann's designs, it stands seemingly alone in his canon.

Fittingly Adolf Loos has a floor to himself, fittingly because while their are parallels to Wagner and Hoffmann, Loos was in many regards ideologically opposite them, understood furniture design from another perspective; whereas, and generalising to the point of falsehood, Wagner and Hoffmann were concerned with the development of new forms for the new age, Loos was a firm believer in the inherent value of the existing form, forms which need only be modified for the new age. And a position elegantly presented in Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos: the Egyptian stool inspired by contemporary interpretations of Egyptian stools he had seen at Liberty in London, the Greek Klismos informed backrest of the dining chairs he developed for Eugen Stössler or the simple wooden side chair to be found in his Gentleman's Room for Georg Roy's apartment, a work clearly based on the vernacular Alpine Bauernstuhl, but bequeathed a very reserved, rational and thoroughly polite metropolitan manner, being among a swathe of references to classical and established forms that can be found in the Loos presentation.

Although in context of the exhibition Wagner, Hoffmann, and Loos exist individually for themselves, there does exists a dialogue between them, one finds similarities, formally, materially, constructively, but also differences, for all ideologically, and it is in this dialogue that one finds the core of the exhibition: the exploration of how the three approached an answer to the question of appropriate, meaningful furniture and furnishings for the coming age. Or as Otto Wagner phrased it in a 1914 quote presented in the exhibition, "All modern creations must correspond to the materials and demands of the present if they are to suit modern Man". The question was, how?

A quote which over a century later remains as valid as ever, and a question which is at the heart of the development of contemporary furniture design and a question where similarly contrasting attempts at approaching an answer can be found in all contemporary epochs: be it in the contrast between a designer such as Erich Dieckmann and his Bauhaus contemporaries in the immediate wake of the Wiener Moderne; a generation and a bit later in America where the likes of the Eamses or Eero Saarinen sought the new while Edward J Wormley remained committed to updating the established, or in Denmark where a Børge Mogensen or a Hans J. Wegner reinterpreted the traditional, vernacular, while a Verner Panton or an Arne Jacobsen went their own ways. And a question which remains as pertinent today, not least because with our myriad materials, production process and aesthetic understandings, but also our increased awareness of the fragility of our social, economic and ecological structures the need for furniture design to reflect contemporary realities is arguably greater, and the how more complex, than it ever was.

Again we're generalising to the point of falsehood, but in such a comparison, in such a historical progression, one understands the relevance of the exhibition Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos for contemporary furniture design. And of the designers Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos for contemporary furniture design.

In addition to the three central protagonists Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos also discusses furniture and interior design of the Wiener Moderne in context of both contemporary Viennese manufacturers and the trio's customers; the latter being an important but easily overlooked component of the development of architecture and design, not least because, then as now, designers and architects can have as many ideas as they want, develop as many positions as they want, but if there is no-one around to pay for them, to enable the tangible realisation, they remain but ideas and positions.

Similarly one has to have manufacturing partners who understand what you want and who can help you achieve that. Yet as with the role of the customer the role of the manufacturer is all too often overlooked in explorations of furniture design history. One can all to easily assume the designer designed, the manufacturer, manufactured. Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos helps explain the reality. In addition to introducing internationally known Viennese firms such as Gebrüder Thonet, J & J Kohn, or the textile manufacturer Backhausen, Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos also introduces lesser well known, if every bit as important, relevant, firms such such as Portois & Fix, Bothe & Ehrmann, Bernhard Ludwig or Josef Veillich and in doing so not only explains the vitality of the furniture production scene in Vienna at the time, but that the development of the furniture and interiors of the period was not alone the work of the designers, but rather resulted from a close cooperation with manufacturers and master craftsmen. A state of affairs one finds throughout the history of contemporary furniture design, and one which if properly analysed results in a very important conclusion.

A particularly pleasing fourth voice complimenting those of the artists, patrons and producers is that of contemporary critics and journalists, their comments and reviews not only helping setting the works in context but also being a reminder that the works were realised in a time when people thought about furniture, interiors, design, understood them as cultural goods, saw beyond the object and didn't just idly heart an extensively post-produced PR photo on Instagram as a means to stave of boredom while waiting for the bus.

Staged in an eloquently reserved and unobtrusive exhibition design concept, Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos is despite the focus on ensembles very much a chairs on pedestals exhibition, yet one which because of the focus on ensembles doesn't suffer from the fact. What is particularly satisfying is that each designer is represented by a relatively small number of projects, relative that is to the innumerate they realised, many of which still exist in the Höfe and Gassen of Vienna, and pleasing because it stops the exhibition becoming tedious, ensures that it moves along at a good pace and takes the visitor with it. The numerous background texts and object descriptions providing not only the factual and contextual basis to the physical objects, but also disrupting the flow in a manner that is both supportive and entertaining.

Being as it is an exhibition largely populated by chairs and furnishings, if you're not interested in such (a) why are you reading this? (b) why have read this far? and (c) you're not going to get a whole lot from the exhibition. As an exhibition it does explain a little about the social economic history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as it approached its end, and also about the same in Vienna as it achieved its cultural highpoint, and therefore does help set the Wiener Moderne in a wider context; is however largely and inescapably about furniture. And that in a very intense manner. If that doesn't sound like you're thing, probably better visit another exhibition in Vienna. If if does, Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos and Viennese Modernist Furniture Design. Artists, Patrons, Producers provides on the one level a very accessible introduction to the work of its three protagonists and on another, higher, level a very concise exploration on the formal, aesthetic, functional and material evolution of furniture design at the turn of the 19th/20th century and how the nature of those changes and the thinking that led to them helped bring us to where we are today. And in all probability will take us to tomorrow.

Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos and Viennese Modernist Furniture Design. Artists, Patrons, Producers runs at the Hofmobiliendepot, Andreasgasse 7, 1070 Vienna, until Sunday October 7th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.hofmobiliendepot.at