The only FAQ not answered by the smow FAQs is the one that begins, "What is smow........?"

And as smow grows and grows so too does the F with which the Q is A'd.

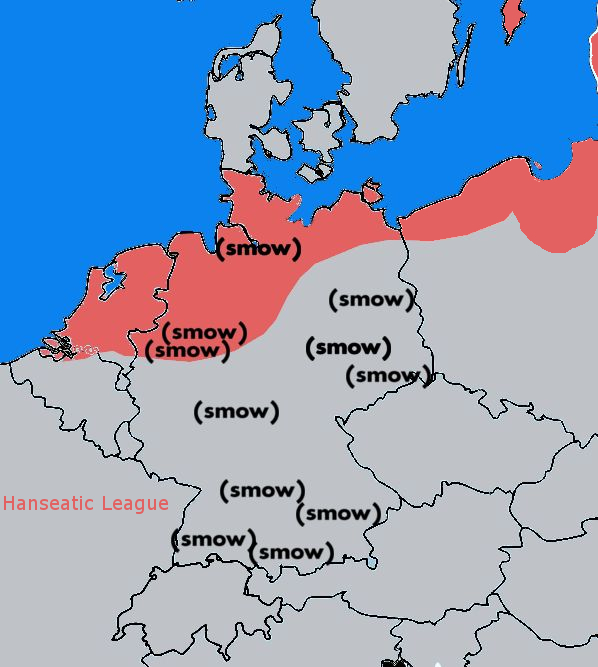

The answer in one sense is very simple, smow trade in furniture, lighting and home/office accessories through a series of showrooms and online shops. But that only partly explains "smow". Doesn't explain the how, who, why and wherefore. Nor the richness. Explaining the true smow is in many respects best achieved by exploring another trading institution whose superficial simplicity hides its true depth of character ..... The Hanseatic League.

While the popular image of the Hanseatic League is one of cheerfully clad, medieval maritime merchants, invariably chasing, or being chased by, pirates: such is an almost childishly naive image. As an international trading network which over the course of some five centuries played a key role in the economic and political development of Europe, the (hi)story of the Hanseatic League is as multi-layered, inter-layered and vividly-richly-layered, as it is simple.

And while smow cannot (yet) boast such a long tradition, nor (yet) such a sphere of influence, the comparisons are (already) many.

Not that we are in any sense appropriating die Hanse for smow. We're not invoking die Hanse. Our aim is simply through exploring what die Hanse was, to approach an understanding of what smow is.

Or put another way....

In 1470 a dispute between the English King and the Hanseatic traders in London saw the Lübeck Jurist Johannes Osthusen compose one of the most famous definitions of the "Hanza Theutonica", the spirit of which, we feel, is particularly well captured in the summary by Angelo Pichierri1:

"The Hanseatic League is not a societas (company): it has no common goods, and each of the merchants trades for themselves. It is not a collegium (corporation): it consists of cities far apart from one another. It is not a universitas (collective): it has no common property, neither a common fund, nor a common seal or common agents or representatives. The Hanseatic League is "nothing more" than a steadfast confederation (firma confederatio) of cities with one single aim, namely to promote sea and land trade and to protect its merchants from pirates and bandits"

Or alternatively.......

"smow is not a societas (company): it has no common goods, and each of the merchants trades for themselves. It is not a collegium (corporation): it consists of showrooms far apart from one another. It is not a universitas (collective): it has no common property, neither a common fund, nor a common seal or common agents or representatives. smow is "nothing more" than a steadfast confederation (firma confederatio) of showrooms with one single aim, namely to promote home and office furniture industry and to protect its consummers from pirates and bandits."

And the deeper one explores the Hanseatic League......

A major factor in the development of what became the Hanseatic League was the Kontor, the communally operated trading house, and for all the Kontore in London, Bruges, Bergen and Novgorod. It was these Kontore which allowed the traders on the one hand to become independent of their home cities, and secondly to establish the international networks on which the Hanseatic League was subsequently built.

The term Kontor originates from the Latin computāre, and transfers through the French comptoir. computāre also gave rise to the French term computer...... and just as the history of the Hanseatic League is founded on their computāre/Kontore, so the history of smow is founded on computāre/computers, allowing as they did the proto-smow to establish its decentralised, international trading network. Albeit not through outposts in London, Bruges, Bergen or Novgorod, but through one in Rostock, a city who's wealth of native programming, databank and spreadsheet expertise allowed the development of smow online.

Yet much as the Kontore weren't the Hanseatic League, just the necessary prerequisite, so to should smow online never be confused with smow. For while important, a necessary prerequisite, it is, as with the Kontore, but a node in a wider, autonomous, network.

As Johannes Osthusen's definition makes very clear, the Hanseatic League was a voluntary network. No-one had control, no-one had the final word, no-one could be forced to accept a decision nor follow a resolution. Each city existed for themselves and made use of the collective when they saw an advantage therein. A firma confederatio. Yet what bound them together, what bequeathed the confederatio its firma, was the understanding by all protagonists of the advantages of the collective, be that internally in terms of enabling a more efficient transfer of information and ensuring security on the highways and high seas, or externally in the negotiation of trading privileges.

In context of the latter, the Hanseatic League negotiated with the regional powers of medieval Europe, today smow's negotiating partners are the regional powers of the contemporary European furniture and lighting industries, be that the long established dynasties of Denmark, the younger houses of Holland or the Berg(e) Baron von Chiemgau. The aim remains however the same: to ensure through collective negotiations not only the best possible conditions, but also the highest quality of goods, the speediest of deliveries and the smoothest possible handling of any tensions.

Aims which are naturally abetted and fostered by extending networks.

As a confederation the Hanseatic League was based in northern Germany, the reason being quite simply a common language, Niederdeutsch; today with showrooms in Hamburg, Leipzig, Chemnitz, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt and Berlin, smow continue this tradition, albeit expanded through southern German showrooms in Stuttgart, Munich, Kempten and Villingen-Schwenningen, and thus showrooms in Oberdeutsch language region with its colourful canvas of Frankisch, Schwäbisch, Alemannische and Bairische dialects.

A not insignificant development, and one which distinguishes smow fundamentally from the Hanseatic League.

Throughout the middle ages the Oberdeutsch traders were important counterparts and corrivals of the Hanseatic traders: as fellow subjects of the Holy Roman Empire there existed a collegial partnership between the two groups, and an interdependency, the Hanseaten supplying, for example, herring to southern Germany while the Oberdeutsch brought various precious and non-ferrous metals northwards. Despite this they were also tenacious competitors, and in many regards this competition, or perhaps better put the effort invested in the competition, played a role in the ultimate demise of both traditions.

Foolishly.

For as well established trading traditions both had their own strengths, spheres of influence, political positions, economic understandings, and thus factors which can compliment as much as contrast, or as Jean-Jacques Rousseau opined in context of the formation of civil societies, "... the only way in which they can preserve themselves is by uniting their separate powers in a combination strong enough to overcome any resistance, uniting them so that their powers are directed by a single motive and act in concert"; words which came some 100 years too late for the Hanseaten and Oberdeutsch but which in many regards are mirrored in smow2 to allow not only for an institution which can be considered as a, logical, synthesis of the two traditions, but for all as a progressive, free-thinking, de-central, international network underpinned by ideals of collective unity.

And computāre.

The above is but a brief, necessarily incomplete, synopsis of not only the Hanseatic League, but of the comparison with smow, we have, for example, not touched upon the comparison of contemporary Leipzig-Lindenau with medieval Lübeck, the importance of relationships with Basel, Pirates, the comparison of the etymologies of the terms Hanse and smow, far less the perennial problems and headaches caused by Cologne, such will however be dealt with in the forthcoming exhibition and book.

Despite the brevity, one can however see not only the parallels between the Hanseatic League and smow, and how understanding the former leads to a better comprehension of the latter, but of the helical nature of existence and the inescapable fact that understanding the past is always the most important step in preparing for the future. Or designing for the future.

And where, we hear you ask, does smow blog fit in to this scheme?

And thus, once again dear reader, you pose the wrong question.

Don't ask what smow blog would have been in the Hanseatic League, ask what he Hanseatic League would have been with smow blog? When it had had a parallel existent institution that wasn't interested in trading, sales, profits, market share, but who understood that beyond such there existed the object as an entity with its own cultural, social and technological relevance. Objects which when considered without the compulsion of profit, shone in a whole new light, or imploded in their own ridiculous pomposity. And so yes we'd have questioned what is so particular and fascinating about "Danish herring", it is not a herring like all other, just raised to a mythical level by convention and lazy scribes? Why must the cloth-makers bring out new colours and patterns every 15 months? To reflect some current fad in the Courts of Flanders? Is that sustainable? We'd have argued for greater use of 3D printing as an alternative to transporting goods, reflected on the brick as a contemporary building material, spoken with Till Eulenspiegel about the reality of life as a freelance roving jester, and become dangerously obsessed with the development of the so-called "chair". And generally tried to expand the lines of Hanseatic vision, exploring the cultural, social, technical and economic conditions from which it arose, the continually changing nature of those in which it exists, and thus, possibly, allowed them to have existed a little longer.

1The full defence by Johannes Osthusen can be found in the Hansisches Urkundenbuch

2For a deeper, more complete, discussion on this subject we refer you to the essay, "The Social Contract in the age of e-commerce" by A. Kari in Annals of the Iocularian Society, Vol 145, 2013, and the book "Enlightenment for Unenlightened Times. New, old, approaches to global furniture trading" by Sella Tabernam, Scocie Verlag, Zossen, 2017.

Assuming that is anyone actually read our musings.........