Following on from the Collective in 2015, Movement in 2016 and Substance in 2017, the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau's annual theme for 2018 is the Standard; a central component of the teaching at Bauhaus Dessau yet one which is and was freely open to artistic, technological and functional interpretation.

And one the Bauhäusler freely interpreted artistically, technologically and functionally

The first exhibition in context of the annual theme explores the work of the German architect Carl Fieger, how he applied his understanding and interpretations of standardisation of architecture and design from his days at Bauhaus in the 1920s to his time at the East German Bauakademie in the 1950s, how he evolved and developed as an architect in that period and his contemporary relevance.

Born in Mainz on 15th June 1893 Carl Fieger studied from 1908 to 1911 at the Kunst und Baugewerkschule Mainz before joining the office of Peter Behrens in Babelsberg. Following two years with Behrens Carl Fieger moved to Berlin and Walter Gropius, himself a Behrens' alumnus, and with whom, and allowing for a short First World War enforced break, Fieger worked for some 14 years; the partnership ending with a 1933 imposed Employment Ban on Fieger, and Gropius's emigration to England in 1934.

Post-Second World War Carl Fieger returned to Dessau where he contributed to the rebuilding effort, and assisted Hubert Hoffmann in his, ill-fated, attempt to re-open Bauhaus Dessau, before in 1952 taking up a position as a research assistant in the Institut für Wohnungsbau at the Deutsche Bauakademie in East Berlin; in which context he developed the first Plattenbau - sectional prefabricated building - the typology that would come to define DDR construction, before a stroke in late 1953 resulted in an enforced retirement.

Carl Fieger died in Dessau on November 21st 1960, leaving not only an oeuvre of work that helps chart and explain both his own journey and that of architectural thinking in the first half of the 20th century, but also an influence sown through being at the centre of numerous key developments in 20th century architecture.

Yet despite his role and importance to the development of architecture, Carl Fieger remains relatively unknown. At least popularly.

Carl Fieger. From Bauhaus to Bauakademie is an attempt to rectify that position, and therefore, and very logically, opens with a fulsome biographical introduction, one which highlights three central periods of Carl Fieger's career. Three periods we'll happily take over.

In the first decades of the 20th century one of the most influential, progressive and productive architectural offices in context of German Neue Sachlichkeit was that of Peter Behrens in Babelsberg. How, why, Carl Fieger came to be in the employ of Behrens is lost in the mists of time, what is clear however is that for a young architect there were few more enticing addresses at that period. In addition to Walter Gropius, Behrens' atelier had also been home to a young Adolf Meyer, who would later become Gropius's office manager, collaborator, and was also closely involved with the Neues Frankfurt project, while during Fieger's time with Behrens he worked alongside the likes of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and for a couple of months, a young Swiss architect by the name of Charles Edouard Jeanneret-Gris who was currently on tour of Germany studying the contemporary applied arts movement.

During his time with Behrens Carl Fieger was principally involved with the development of the neoclassicist, highly representative, Embassy of the German Empire in St Petersburg; however parallel the office also completed works such as Haus Wiegand in Berlin, the AEG workers' estate in Hennigsdorf or the Mannesmann-Haus in Düsseldorf with its, at the time, revolutionary variable floor plan system based on a standard unit. Parallel Gropius and Meyer were realising their Fagus-Werk in Alfeld, a work who's glass curtain wall ushered in a new era in architecture as much as it did light into the factory, and a work who's final construction stages Carl Fieger would, presumably, have experience in Gropius's office.

Thus in 1914, and just some three years after leaving college, Carl Fieger had not only worked with some of the leading protagonists of contemporary architecture, but experienced first hand the development of some of the most important buildings of the period.

And witnessed one of the most important debates of the period.

At the 1914 Deutsche Werkbund exhibition in Cologne a debate arose about the future direction of architecture and product design, a very fundamental debate which would eventually see more progressive architects such as Gropius and van de Velde split form the more arts and crafts orientated members of the Werkbund.

In essence, this not being the time nor place for a full discussion on the arguments, the so called Typisierungsdebatte was about how architects and designers could best respond to industrialisation, help industry to help them to help society; at the 1914 Werkbund exhibition Hermann Muthesius argued for the universal use of a set number of predefined forms, while the more progressive elements lead by Henry van der Velde defended the artistic freedom of the architect/designer, arguing that while industrial production was desirable, it should follow the artists, not the other way round.

In 1920 Carl Fieger not only rejoined the office of Walter Gropius but was appointed to the staff at Bauhaus Weimar, teaching the compulsory technical drawing course, architecture may never have been taught at Bauhaus but the students were required to learn the basics; basics Carl Fieger understood and which he demonstrated in number of projects realised during his time in Weimar, including a 1924 semi-detached house for doctors, and where he first experimented with colour schemes; a private house in Alfeld for Carl Benscheidt, owner of the Fagus-Werk, and an object who's neoclassicist leanings indicate the Behrens' influence was still strong; and an entry for the 1922 Chicago Tribune Tower contest, an essentially monolithic work with a preponderance of windows, and which indicates that an understanding of contemporary architectural thinking was also strongly present. And a work that one must add very closely resembles the entry from Walter Gropius, an entry Carl Fieger sketched, and which poses the very obvious question as to which came first.

In addition, throughout the nearly 1920s Carl Fieger contributed to, and for all was the responsible draughtsman and sketcher, the contemporary renderer if you will, of numerous projects with Gropius including the Haus Sommerfield in Berlin, the reconstruction of the Stadttheater in Jena, and the Bauhaus Dessau building itself, Fieger's sketches elegantly showing how the form evolved and developed.

Arguably however the defining architectural discussion of the early 1920s concerned the need for hygienic, affordable, urban housing; a discussion that equally arguably was one of the major motors for the development of rational, formalist, modernist architecture, and a discussion that would over time become popularly associated with projects such as Le Corbusier's Cité Frugès in Pessac, the Weissenhofsiedlung Stuttgart, Neue Frankfurt or Werkbundsiedlung Vienna.

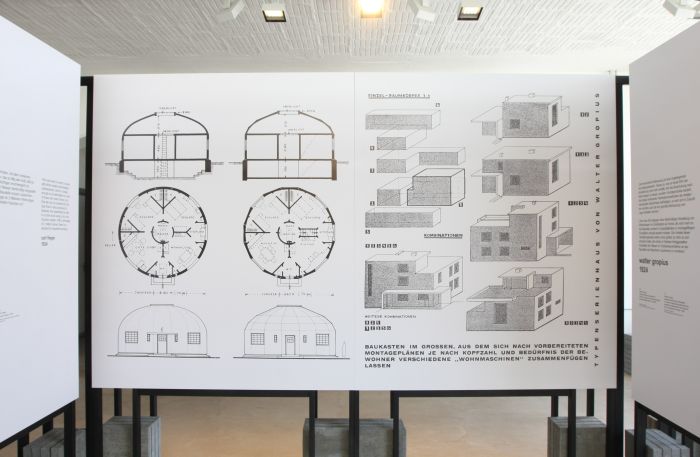

A major component of the inter-war discussion was the need for house production to be industrialised, a step which involved new approaches to house design and new construction processes. And which for all involved standardisation and prefabrication. In 1922, for example, Walter Gropius advanced his Baukasten im Großen (large-scale construction kit) which proposed a modular construction system based on standardised prefabricated components, while in 1923 Le Corbusier defined the house as "a machine for living in", and which should thus be realised by industrial methods. In 1924 Carl Fieger published his position with the Round House; a round house, a sectional round house who's standard wall elements could be industrially produced and which with its prefabricated character allowed for the required hygienic, affordable, urban housing. And a work which in its concept and layout is in many regards similar to the temporary, emergency housing Jean Prouvé developed a decade and more later.

In the middle of the so called functionalism debate, a debate that as with most of those undertaken by totalitarian regimes had less to with debate and more with insulting and demonising, and which as previously noted saw the then Assistant Prime Minister and General Secretary of the SED Walter Ulbricht denounce the “Bauhaus style” as a “hostile manifestation”, Carl Fieger joined the staff of the East German Bauakademie. And promptly developed with his prefabricated Bauakademie building a standardised prefabricated construction principle which stood juxtaposed to the official position of the East German government, being as it was an example of the "concrete boxes" Walter Ulbricht had, bizarrely, denounced as "the expression of formalism’s inability to generate new ideas for the construction industry"1

And which now housed the central East German construction research and development authority.

To hide the fact, and the ruling SED's hypocrisy, Fieger placed a neoclassicist facade on the prefabricated concrete structure; a facade which contained a few pleasingly subtle nods to Karl Friedrich Schinkel's original Berlin Bauakademie from 1836, itself an example of new architectural thinking.

The tragedy of Carl Fieger's stroke is, apart from the much more important personal one, that it came just at the moment when attitudes were changing in the DDR, when the death of Stalin led to an ending of the formalism debate and saw the DDR perform a majestic reverse ferret and embrace the modular, standardised, prefabricated construction system. Thus his stroke denied Carl Fieger the chance, if the late chance, he was by this stage 60, to develop the ideas of standardised industrial housing he had been developing since the 1920s. And that at time when East Germany was in desperate need of quick affordable housing. And is arguably also among the reasons Carl Fieger remains so relativity unknown, he never had that moment that was exclusively his.

Despite his current relative obscurity, that wasn't always the case. In 1962 Carl Fieger was subject of the first solo artist exhibition at the Bauhaus Archiv at its then home in Darmstadt, and was also the subject of the first solo artist exhibition in the newly consecrated Bauhaus Dessau in 1978. And then, and as with so many of his contemporaries, whereby the names Herbert Hirche or Marianne Brandt, spring particularly to mind, he slipped from view.

It is therefore especially fitting that having been the subject of the first solo artist exhibition in Dessau, he is also the subject of the last before the museum moves to its new home next year.

Having set the scene and context with the biographical presentation and the highlighting of the three phases of his career, the exhibition moves on to his work in detail. Running chronologically from his time with Peter Behrens onto his time with Gropius, the move from Weimar to Dessau, and ultimately to his post-Second World War activities, the flow is neatly and regularly interrupted by small detours highlighting some of his key projects including his Kornhaus restaurant in Dessau, complete with plans for an unreleased, and very interesting sounding, external lighting concept and his own house in Dessau. Projects which are not only based on the judicious use of prefabricated elements, but which also demonstrate that the architecture of that period needn't only be quadratic, can also express itself just as clearly in flowing curves.

The greater part of the exhibition space is taken up by a 1:1 floor plan of Fieger's Deassu house with examples of his furniture design placed appropriately; including his answer to Marcel Breuer's B3 Wassily Chair, a work which is not only formally more reduced and calmer than Breuer's but also from the construction is a much more logical and rational piece of work, better standardised, and certainly one more suitable to large scale, industrial production. And one which neatly indicates that in addition to architecture and draughting, Carl Fieger also had an eye for the essentials of furniture design

As a solo exhibition about an architect, From Bauhaus to Bauakademie relies very much on plans and sketches, plans and sketches which help explain Carl Fieger's progression from the waning light of neoclassicism to much more rational positions, yet also how despite that evolution much of his work is in its soul neoclassic, and thus how evolution in architectural thinking needn't mean a distinct break with the past; but for all plans and sketches which underscore the importance of standards, materials and system thinking in his architecture. And plans and sketches which allow the exhibition to function on a number of levels.

Presenting an accessible and open exhibition concept the plans and sketches mean that From Bauhaus to Bauakademie can be enjoyed on a superficial level, which isn't meant snobbishly, but is meant that it allows for a very neatly presented, jargon-free, fleetingly brief introduction to a relatively unknown architect, yet one whose work is relevant and important to fully understanding the development of architecture both in the inter-war years, but also, and when sadly all to briefly, in post-war eastern Germany.

On a higher level the plans and sketches allow for a detailed exploration of not only Carl Fieger's oeuvre, but also of how he developed as an architect over the decades and how his work compares and constants with that of his contemporaries, how it reflects the contemporary thinking and his understanding of the problems of the period and architectures most appropriate response.

And how it poses the question as to why we still don't have proper industrial construction. Why despite all the advances in materials and technology construction is still, as we've noted before, essentially a manual exercise. Before we develop autonomous cars and AI sex dolls, would it not be better, be more socially responsible and socially sustainable, to develop lower cost, high quality, construction systems to allow for the creation of much needed hygienic, affordable, urban housing; or as Carl Fieger phrased it in 1924, "We now need to invent a house with all the modern technological achievement, which is cheap enough to be affordable for most of those who need homes"

Having viewed Carl Fieger. From Bauhaus to Bauakademie we get the impression that 94 years later he'd still be developing and advancing interesting proposals for achieving just that.

Carl Fieger. From Bauhaus to Bauakademie runs at the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Gropiusallee 38, 06846 Dessau-Roßlau until Wednesday October 31st.

1"Das Nationale Aufbauwerk und die Aufgaben der deutschen Architektur" in Die Aufgaben der Deutschen Bauakademie im Kampf um eine deutsche Architektur, Henschelverlag Berlin, 1952

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.bauhaus-dessau.de