The first metaphors may, or may not, have been animal based, but materials are just as adaptable. And few are as adaptable as glass. The Glass Ceiling as the impenetrable, yet invisible boundary. The Heart of Glass as a state of extreme emotional weakness. While in most glass metaphors the focus is an inherent property of glass: transparency.

With the exhibition Welt aus Glas. Transparentes Design the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus Bremen abstract that metaphor to explore the link between transparency in design and architecture, and transparency in society.

While an exhibition about Glass staged by the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus may appear as lazily logical as an exhibition about catholicism staged by the Vatican or a retrospective of Kim Kardashian selfies curated by Kim Kardashian, both Wagenfeld and glass are only incidental to the genesis of the exhibition Welt aus Glas. Transparentes Design [A Glass World. Transparent Design]

Much more the exhibition has its origins in wider social and political discourse, or as Wilhelm Wagenfeld Stiftung Director Dr. Julia Bulk explains, "Regardless of which newspaper you read or which talk show you watch, transparency is a recurring theme, the one voice argues we need more transparency the other that we are fully transparent, and we so decided to investigate if there existed relationships and parallels between transparent objects and transparency in politics and economics."

To this end Welt aus Glass explores transparency in context of selected design related themes including technology, seating, architecture and fashion, before ending with the Gläserner Mensch, the Transparent Citizen, as considered in art/activism projects by the likes of Timm Ulrichs or the Austrian collective Social Impact Aktionsgemeinschaft.

Begins however with, in many respects, the origins of our fascination with transparency, the development of x-rays and micrographs in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century, and thus the ability to see the secrets inside the opaque. And an ability which, both physically, as in x-rays/micrographs, but also metaphysically in terms of psychology/psychoanalysis as developed/practiced by Freud et al, being one of the flames that fired Art Nouveau, and arguably in Art Nouveau one also finds the first appearance of glass as a, at least relative, mass market product, for all in terms of decorative items. The use of glass in more functional goods not coming until the 1920s and 30s with the refinement of pressed glass and thereby the ability to industrially produce glass objects, and a process in which Wilhelm Wagenfeld with his glass teapots, storage jars, et al, played a major, pioneer, role.

A role which Welt aus Glas, quite naturally, celebrates.

A technical draughtsman and silversmith by trade, Wilhelm Wagenfeld first made a name for himself in the metal workshop at Bauhaus Weimar, which raises the question as to how he subsequently came to be so closely associated with glass?

"He became acquainted with Herr Schott from Schott & Genossen, who was so impressed by Wagenfeld that he employed him, and that despite the fact he had next to no experience with glass", explains Dr. Bulk, "Consequently he learnt about glass through visiting Schott's factories, speaking with the technicians, the staff, experimenting, so classic learning by doing and ultimately developed a genuine passion for glass, he once held speech in which he spoke of his love of glass, and said he "had fallen" for the material"

But, we wonder, did he treat his glass design as he would metal design or was it a case of new forms for a new material?

"I think that when you look at his very early work you can see a metal form transposed into glass", answers Dr. Bulk, "but very quickly he learned that the material had its own characteristics, so much so that there ensued a disagreement between Wagenfeld and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, his former teacher at Bauhaus. Moholy-Nagy saw it as a betrayal that Wagenfeld deviated from geometric forms, to which Wagenfeld replied, yes because the material behaves differently to metal and thus should not be treated like metal. And one sees that during his time at Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke he used glass as glass, and didn't make objects from glass that could just as easily have been made from metal; apart from one exception, a prototype for a glass clothes hook, that is clearly a metal hook, in glass. However that was because of the wartime shortage of metal they had to find alternatives"

That hook is presented in Welt aus Glas alongside a pleasingly limited selection of Wagenfeld objects, pleasingly because the exhibition isn't about Wagenfeld, he is "merely", as one of the pioneers of glass design, one of the first to bring transparency to product design and consumer goods, one of the earliest stations on the exhibition's narrative. If a Central Station.

Following on from Wagenfeld and there is a very nice presentation of the evolution of glass coffee percolators, something for all you slow coffee hipsters out there, before the exhibition moves on to the wider exploration of transparency in design and transparency in society.

It's fair to say we have complicated relationship with transparency.

One the one hand we all demand transparency, for all from organisations, authorities and those who control the purse strings, on the other we're are suspect, afraid even, of being too transparent ourselves. In many regards one could argue we expect transparency from public bodies, while demanding an opaque privacy. Which would be OK, were it not for the way private and public increasingly merge and fuse. And the differing ways differing sections of society understand "public" and "private": the one campaigns against the police's use of face recognition video cameras, the other is delighted by the face recognition system of their new fruit based smartphone. And the vast majority, regrettably, have never considered things either way.

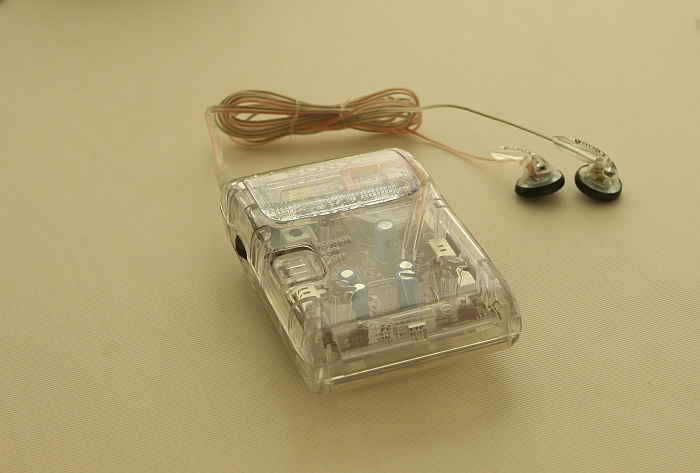

In addition to the general question of how much transparency we need, or should have, comes more fundamental questions of from whose perspective one views transparency. While no-one likes getting body scanned at airports we all grudgingly accept the, more or less, necessity. In contrast when American prisoners are made to use the transparent Sony SRF-39FP radio so that warders can more easily check there are no drugs, weapons etc within, then transparency is not serving the prisoner, merely reminding him of the total control under which he finds himself. For someone at liberty such a transparent radio would be a novelty, something to show off on the bus, laugh about with friends, something innocent.

Then there is the question of how much transparency is useful, and how much is simply show. The transparent television set on display in Welt aus Glas, for example, helping no-one through its transparency, other than technic freaks, the fact that you can see inside providing no functional advantage. It's just marketing. And ain't pretty, or as Dr. Bulk points out, a Dieter Rams would never have released the transparent Braun radio displayed nearby. And much as our technical goods needn't be transparent, so too, if we're all honest, has politics and economics never been fully transparent. Is largely a political PR show in contrast to commercial marekting. But is that important? Would it help us to have full transparency? Or is the impression of transparency we get enough to satisfy, and leaving us free to enjoy our lives? Or does such partial transparency lead ultimately to Fake News, an alternative partial transparency?

Welt aus Glas is an opportunity to consider such, and related, questions. As an exhibition it isn't always instantly obvious, or perhaps better put, not instantly transparent. You need to work at it a little and add your own position to the transparent voids.

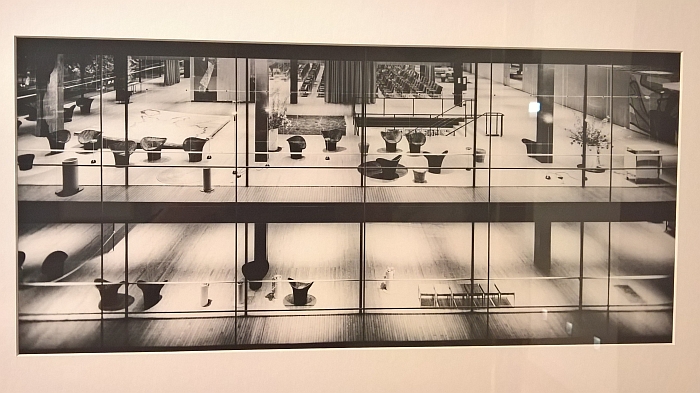

Although it is slightly over exaggerating to claim that the flow of the exhibition is from one of delight and joy at the discovery of transparency to one of suspicion and mistrust, there is a definitive tendency in that direction. Is however not a linear flow, through the progression there are occasionally peaks, peaks where the metaphor glass/transparency is unequivocally positive, such as Walter Gropius's Bauhaus Dessau, a symbol of not only our ability to master and tame this new technology, but also of openness, freedom and health as contrasted by the stuffy, closed society with which the avant-garde wanted to break; the German Pavilions at the 1958 World Expo in Brussels by Sep Ruf and Egon Eiermann as symbols that Germany had nothing to hide, and arguably also symbols that it was very much open for business; or the Transparent Speakers from Swedish design studio People People which employ transparency as tool for encouraging repairing contemporary electronic devices as opposed to planned obsolescence.

But in general the story is of a relationship being placed ever more in question, and where transparency is being understood as something forced upon us, that we have to accept rather than seek.

And this translocation from something considered positive to something we mistrust, even regret, is a repeating theme in society, or at least our oh so advanced and civilised western society. Remember how great it was that oil could be used for so many things, for all synthetic materials and powering cars? Remember how grateful we all were for pesticides and the effortless way they advanced global agriculture? And remember how we all filled our homes with smart speakers which listened to our conversations, tracked our movements and sent the data to Californian tech conglomerates?

Only with distance and reflection can things be truly placed in context and understood, or at least their full complexity understood, if not always understood in their full complexity.

As an exhibition Welt aus Glas makes it clear that we still haven't understood our relationship to transparency. But keep on being drawn to it like the proverbial moth to a flame. With all the risks that entails.

A well paced, intelligently arranged and accessible exhibition, with, yes, a lot of glass objects behind glass, Welt aus Glas can be enjoyed for the, at times, absurd and obtuse ways people have employed glass, as a simple journey through a century or so of glass as part of everyday lives. Or put another way, it doesn't shout out the parallels that can be drawn from transparent product design and transparent civil design, far less transparent architecture and transparent communities. The links/metaphors are however there, visible, it’s up to you to follow those which interest you and reach your own conclusions.

And what does Dr. Julia Bulk hope visitors take with them?

"First that they consider those transparent objects they themselves possess in context of the exhibition themes, and secondly that they consider afresh the question of the Transparent Citizen, the question of how much transparency is necessary, and where must we take care that things don't become too transparent. This interrelationship is a fascinating, and important, concept, and one that will continue to concern and challenge us for decades to come."

No-one is saying this interrelationship began with a glass teapot. But in a way it did.

Welt aus Glas. Transparentes Design runs at the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus, Am Wall 209, 28195 Bremen until Sunday April 22nd

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.wilhelm-wagenfeld-stiftung.de