Architects are always very keen to stress how they are working in the interests of society, for society. Often selflessly so.

Yet little polarises society quite like architecture.

And no architecture polarises quite like Brutalism.

Whereas in discourses on other architectural genres the middle ground is a place where those of moderate opinions can meet objectively and attempt to approach one another's position: there are no Brutalism moderates.

With the exhibition SOS Brutalism - Save the Concrete Monsters, the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt becomes that objective middle ground and thereby enables a very welcome discussion on Brutalism, its origins and its legacy.

Arguably because the visual impression of many, most?, Brutalist constructions leaves only little room for alternative understandings, a lot of misconceptions exist about Brutalism. For all that the term derives from "brutal", as in savagely violent. It doesn't. Rather it is rooted in the significantly less aggressive French term brut, in the sense of direct or raw. Arguably also dry.

Similarly the fact that many, most?, Brutalist constructions are concrete leads to the misconception that Brutalist works must be made of concrete. A misconception the exhibition title, and presentation, nicely, regrettably?, reinforces.They needn’t be.

And so, and before we proceed any further with misconceptions, what is "Brutalist"

"The British architecture critic Reyner Banham proposed three factors", explains exhibition curator Oliver Elser, "exposed material, visibility of the structure and the strength of the visual image, so the overall composition, and here we have added as a criteria the rhetorical quality of the building. These are in no sense unequivocal definitions, but one can generally distinguish most Brutalist works from late Modernist works in that they have something brash, overly expressive and yes, often something brutal"

And that employed deliberately and provocatively by the genre's protagonists. Something SOS Brutalism very neatly demonstrates.

As an architectural genre Brutalism arose in the 1950s, the first Brutalist building widely considered the 1954 Hunstanton School in Norfolk, England by Peter and Alison Smithson; a couple who a year earlier had co-initiated the so-called Team X movement within the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne, CIAM, as an attempt to move away from the positions of older CIAM members, including the dominating positions of Le Corbusier. An architect not averse himself to a bit Béton brut, exposed concrete.

While the Hunstanton School is a very modest, reserved affair in contrast to many Brutalist works, and certainly when compared to later Smithson projects such as Robin Hood Gardens, London, the principles behind it, for all the structural clarity and focus on lo-cost, local materials, soon spread globally, largely as a reaction of a younger generation of architects to the prevailing post-war social, political and economic conditions, and/or as a political statement by post-war regimes of their independence and self-determination, of a new post-war generation's independence and self-determination.

Not that the works necessarily pleased all who were exposed to them. For many the direct, raw works were more alienating than inviting. Ugly rather than attractive. Brutal rather than brut. And for many they still are. Still polarise

According to Oliver Elser, while the principle Brutalist era lasted until the late 1960s, and such for little more than a decade, in many regions it continued until the end of the late 1980s, for all in those Soviet Block nations. The end of the Cold War arguably ending the philosophical argument; while the high manpower required, and thus relatively high cost of construction, increasingly made Brutalist works unattractive, especially for public bodies who through the construction of civic buildings, educational facilities and social housing had long been a major driving force in Brutalism.

And while today there are architects working in a Brutalist fashion, the Brutalist buildings we have are generally fifty, sixty years old.

And tend to polarise.

Often quite strongly.

Very strongly.

And this opposition to the buildings sees many of them endangered.

SOS Brutalism was initially conceived as an inventory of those endangered buildings, if you will a Brutalist Red List; however, very quickly the curators decided to expand their scope and instead compile an inventory of all Brutalist works, one which goes beyond those visuals which so easily transport over social media, to look at the history of the works and their current state and position.

And also highlight those that are endangered.

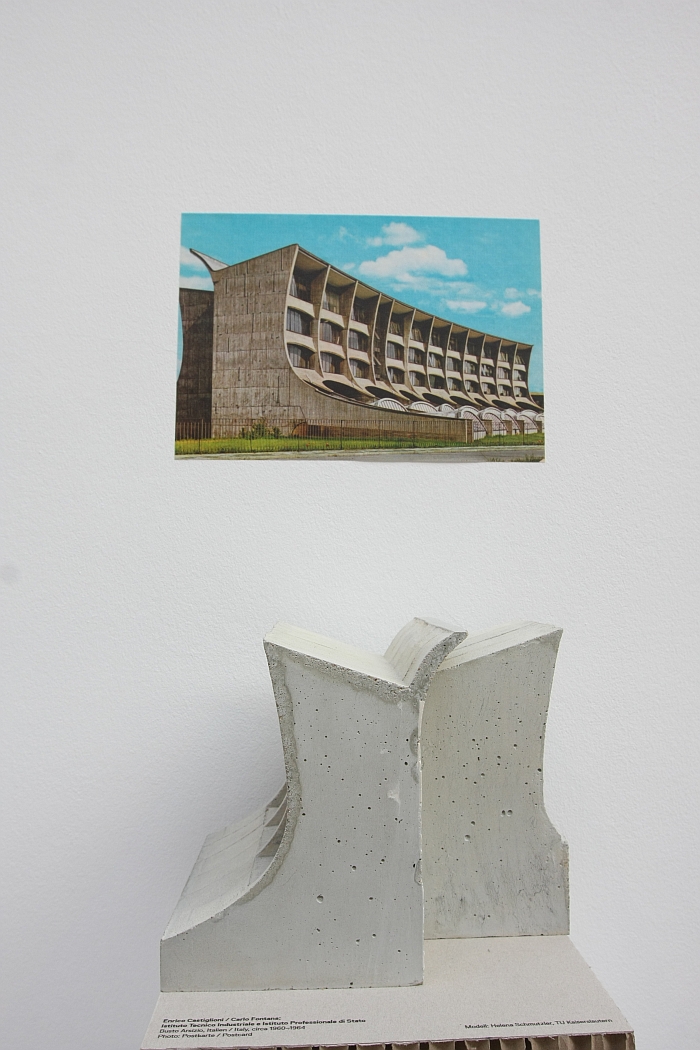

To this end SOS Brutalism presents a mix of small concrete casts and larger cardboard models of selected Brutalist works, models supplemented and complimented by texts and photos which explain the background to and position of Brutalism globally. Necessarily brief the texts do however allow for an informative insight into the local peculiarities of the global phenomenon while also making very clear just how widespread Brutalism is/was.

Beyond the global exploration SOS Brutalism also sets five foci, each of which is given its own, necessarily brief, information boards: concrete as a material, concrete churches, Le Corbusier as Urvater, so a pre-Brutalist Brutalist, campaigns to save Brutalist works and also female Brutalist architects, the final section being in many regards an extension of the Frau Architekten exhibition also currently running at DAM.

An accessible, informative and entertaining exhibition, the presentation in Frankfurt is however in many regards simply a physical extension of the projects larger existence, as an online platform #SOSBrutalism, a platform which thanks to public contributions has grown from an original 200 projects proposed by the DAM to over 1000. And one which should/will continue to grow: the idea being that the public not only suggest missing works, but also add background information and photographs, thereby helping create a virtual database of Brutalist architecture as a public research and information tool. And also, perhaps, a grassroots movement in support of saving Brutalist buildings.

Beyond being a call to rescue endangered buildings the SOS in the title can arguably also be seen as referring to Save Our Sobriquet, of rescuing the term "Brutalism" from the negative connotations, of allowing the buildings to exist independent of any preconceptions, misconceptions, arising from a more or less meaningful, inherently unequivocal, categorisation.

And something it does particularly well through both its focus on campaigns to save Brutalist works, campaigns which highlight the local importance and relevance of individual objects, and also more generally in highlighting the connections indivíduals can have with works. Whereby, and on a very, very personal note, one of the genuine highlights of the exhibition for us is the concrete cast of Gala Fairydean FC's stand. Referred to as the "main stand" - it's the only one at Fairydean's Netherdale home - a sporting youth and misspent adolescence meaning we are familiar with pretty much every inch of Peter Womersley's construction, a construction which has arguably only second place in our affections behind his nearby atelier for the textile designer Bernat Klein; a work that despite its unremitting character blends effortlessly with the surrounding forest. It's visual lightness almost camouflaging it. And not just Womersley's work struck a deep chord with us, also Ernő Goldfinger's Trellick Tower in London. No-one who has ever experienced the sheer terror of the way it dominates the quaint mews of Notting Hill can doubt its brilliance. One can become emotionally attached to Brutalism.

And so, yes, for us the case for saving Brutalist architecture was made long before we visited the exhibition; for us however the exhibition brought new perspectives and new impressions of Brutalism as a global phenomenon, as a force of experimentation and political expression, but also an expression of an attempt to create a more democratic, representative architecture.

Instead it polarised.

And therefore the ultimate success of SOS Brutalism relies on the openness with which visitors approach it.

We'd advise very.

As an exhibition SOS Brutalism is firmly the opinion that while not all Brutalist buildings are automatically works of genius, and certainly many that exist today should not be built today, that Brutalist architecture can be endearing, can be charming, can be worth saving. And not just from historic or architecture perspectives, but also pure pragmatic environmental and economic: there is a lot of energy and material involved, and if the building is sound, why not use it? Because of its form? Having viewed SOS Brutalism you might not agree, but you will have a much better, factual, objective understanding of what you don't like.

SOS Brutalism - Save the Concrete Monsters is a bilingual German/English exhibition and runs at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Schaumainkai 43, 60596 Frankfurt am Main until Sunday April 2nd

Full details can be found at http://dam-online.de

The SOS Brutalism platform can be found at sosbrutalism.org