Whereas most design schools stage their annual exhibition at the end of the summer semester, there are exceptions, such as the Folkwang Universität der Künste, Essen, who present theirs just before the start of the winter semester.

And so nigh on three months after all others have ended.

Because, one wonders, they fear its brilliant glow would place all other schools in its shade, and they want to remain fair to their colleagues elsewhere? Because they have something to hide, and hope by waiting till October no one will visit?

Our #campustour may have long since been parked up for 2017, but keen to learn more we cranked it up and set course for Germany's Ruhrgebiet.......

In Norse mythology Fólkvangr is that region of the afterlife presided over by the goddess Freyja, and where half of those slain in combat spend eternity. Through her associations with love, beauty, gold and fertility Freyja can be considered a Norse Venus or a Norse Aphrodite.

In Germanic reformism Folkwang was/is an initiative established in the early 20th century by the art collector and patron Karl Ernst Osthaus. Seeking to employ art to improve and enrich everyday society, if you will, seeking through making art accessible to all to foster a new, aesthetic, culture as an alternative to the harsh, formless, reality of the period, Karl Ernst Osthaus established the Folkwang Museum in 1902 as both a permanent home for his various collections and as a space where people of all backgrounds could meet on an equal basis not just to enjoy the art, but to learn from it, and from each other

In 1920 Osthaus established the first Folkwang School with the aim of unifying the arts through education, and while he himself passed away in 1921 his ideas continued in the form of the Folkwangschule für Musik, Tanz und Sprechen, an institution established in 1927 and expanded in 1928 through the assimilation of the Fachschule für Gestaltung.

The intervening decades have seen the school and its various institutions repeatedly separate, fuse, reform, rename and ultimately reunite: the contemporary Folkwang Universität der Künste taking on its current form in 2007, and name in 2010.

In addition to Bachelor studies in Photography, Industrial Design and Communication Design, the Folkwang Universität der Künste offers a range of Masters programmes, the most idiosyncratic being the Folkwang Graduate Programm Gestaltung Heterotopia in which students, in effect, construct their own curriculum with the aim of developing their own interdisciplinary project free from the constraints of traditional academic dogma.

The "Finale" in Finale 2017 refers not only to the presentation of final, graduation, projects, but also to the fact it represented one of the final acts for the photography and design students in the Folkwang's SANAA building before they move to their new home on the other side of Essen's Zeche Zollverein, colliery turned culture complex.

Constructed in 2006 the SANAA building could be considered a contemporary exposed concrete construction; is in reality a series of windows interrupted by arbitrary slabs of concrete. And as such a building which has the potential to distract from the works on show: with every turn, movement and change of position a new vista opening to you, passing over and taking you far, far beyond the projects on show.

Or at least physically; ideologically and conceptually, one or the other project took you to places imperceptible to the tangible world.....

Rather than simply creating an object for her Industrial Design BA Seungmin Baek sought to explore the creative process itself by transposing formal, functional and material elements of a broom to a chair. Not make a chair from a broom, but make a chair that is intrinsically a broom. But is actually a chair.

And thereby a project which through limiting the conditions by which a chair is created, not only poses a few interesting questions about chair design, but also highlights how important intuition is in the process; that a chair isn't just a physical, functional object, but that it must by necessity also contain a little of the designer's understanding of the object, an understanding which is to be applied in an unconstrained manner.

Consequently, and unavoidably, the result of Seungmin's research and considerations is/was a collection of chairs which although undeniably sitting objects lacked that certain je ne sais quoi that makes a sitting object a chair. Which isn't to say the results were unappealing, or even banal, far from it, presenting as they did very specific, playfully original, objects, including a stool on castors and broom heads which sweeps the floor as you roll across it.

Which is obviously preposterous.

As in, fascinating.

And if we're honest, we've spent most of our time since Essen imaging all manner of similar objects, for all office furniture objects, and largely aimed at Start-Ups who, invariably, lack both the money to pay an office cleaner and the aptitude to do it themselves, and consequently for whom the opportunity to sweep the floor as you go about revolutionising the world would be an invaluable help.

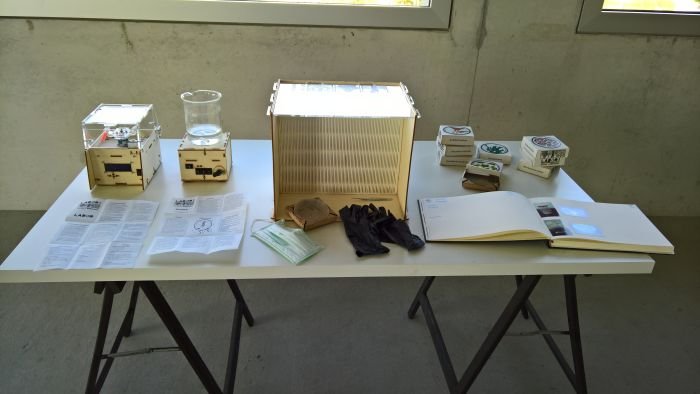

Created in context of the Graduate Programme Gestaltung Heterotopia, Labor für Zucht und Ordnung - Laboratory for Culture and Order* - is an exploration of Biodesign/Biotechnology in design/Biohacking which, and with apologies to Julia should we inadvertently mis-summarise, can in many regards be understood as a call to us all to not only undertake more biological exploration, but to learn how to use those natural resources at our disposal rather than relying on industrial derivatives thereof.

Much as one of the problems with 3D printing and other rapid processing technologies is making the technology available in a such a manner that it is accessible to as wide a range of people of possible, so to is one of the greatest challenges in the widespread uptake of the many interesting biodesign projects, the resources one requires, coupled to a general belief among the population that biology and biotechnology is difficult.

As Labor für Zucht und Ordnung demonstrates the technology is available, and is relatively straight forward, and while, and as with all subjects, the deeper one goes the more complex it becomes, at surface level biology/biotechnology is very straight forward. You just need to start. There being little quite like learning by doing. Which is what Labor für Zucht und Ordnung demands/proposes we do.

We're not sure where Julia plans to take her research, but aside from the hope that such could encourage us all to live a little more sustainably through better utilising natural resources, what appeals to us is the opportunity such a project offers to allow for a more informed discourse on biotechnology, one based less on the emotional arguments that are currently employed and more on a practical understanding. For just as digital technology is advancing so is biotechnology, and we all need to/should be involved in the discourse.

Thus making Labor für Zucht und Ordnung in many respects a very Folkwangian project.

Whereas with E110 Sebastian Dukat did present a folding chair concept, for us the more interesting part of the project was the study into the history and development of folding chairs Sebastian undertook, a study coupled to the question of the genre's contemporary roll as a domestic furniture object.

Or perhaps better put, what most attracted us to the project was the study into the history and development of folding chairs; because we haven't seen it and so can't comment on it. At Finale 2017 Sebastian did however present a poster of 100 folding chairs from 1890 until today. And a poster which, for us, raised all manner of questions on the phenomenon that is the folding chair. Not least, why do so many designers spend so much effort ensuring that folding chairs look like non-folding chairs? And given that they do, why is there so little variety in folding chairs forms?

Questions we plan to come back to at some point real soon.

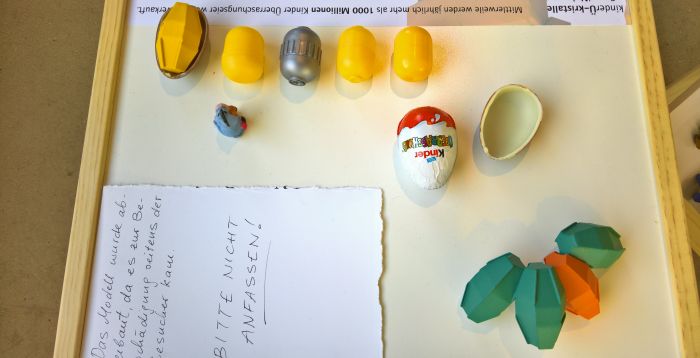

While, arguably, the most important question in terms of the Kinder Egg is the one about their necessity, one must also question the logic and justification of the plastic capsule in which the toy is located. Landing as they invariably do in the rubbish.

Sergej Nejman began with similar considerations and rather than completely altering the concept, made a few marginal, though intrinsic, changes to said capsule, and thereby transforming it from a throwaway piece of packaging to a modular construction system. Or at least a component of a modular construction system which allows children to create structures and objects from their collected capsules. And thereby adding another element to the product: chocolate, toy, and a new piece for your construction system.

At one stop on our #campustour we saw the results of a semester project in which the students were challenged to rethink an existing chocolate product. Each and everyone of them developing a cheap marketing gimmick which added little of real value to the product. While still seeing an awful lot of room for further development, Ü-Kristalle is very much more what we would have hoped for, something which adds a value for not only the manufacturer but also the consumer and, when albeit very, very marginally, the environment

Yes, our opening question remains valid, as does the wider question about global consumption the Kinder Egg poses, but Sergej's project neatly demonstrates that through a small alteration in an apparently inalterable object, one can make consumption a little more sustainable. If not any healthier.

* There are about 8,000,000 possible ways of translating and interpreting Labor für Zucht und Ordnung and without talking to Julia it is impossible to be certain of having gotten it correct.....

Full details on the Folkwang Universität der Künste can be found at www.folkwang-uni.de